TWILIGHT AND FOG: HOW EARL SCRUGGS AND ROD SERLING CHANGED POP CULTURE

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the births of two of the twentieth-century’s most influential pop cultural icons. The year 1924 was bracketed by the births of bluegrass banjo legend Earl Scruggs, born six days into the new year, and TV fantasist Rod Serling, born six days before it ended. Seeing as how we are near the mid-point of the year, this might be a good time to celebrate the centennial of both men.

Scruggs and Serling differed from each other in numerous ways – in their backgrounds, their personal lives, their chosen mediums, their personalities, etc. – but both men enjoyed probably their greatest success in the 1960s, a decade which nowadays is remembered primarily as the era when people born in the 1940s – The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Steven Spielberg, Michael Crichton, etc. – began to take center stage in popular culture. But most baby boomers were too young to have much impact on the Sixties, and some of the most important cultural landmarks of that era came from men and women born long before the baby boom.

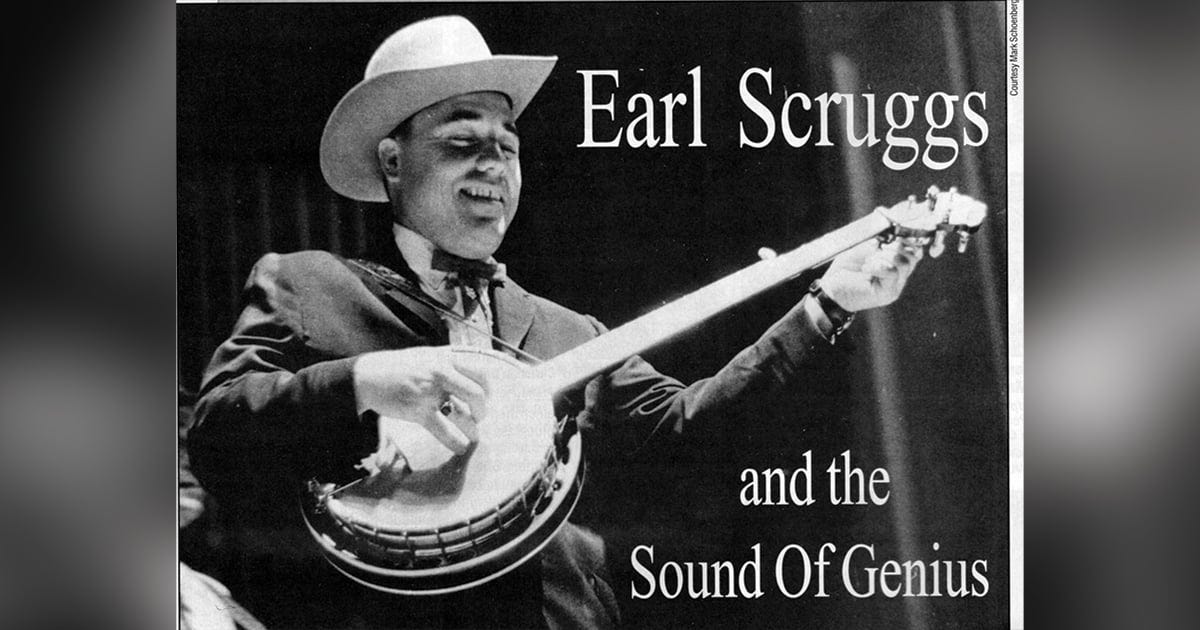

Scruggs was born in Cleveland County, North Carolina, on January 6, 1924, more than two decades before the baby boom began. He grew up poor and, after the age of four, fatherless. Earl was the youngest of five children. All of his siblings, and both of his parents, were amateur musicians. Earl’s father, a farmer and bookkeeper by trade, played banjo in a style known as “frailing,” but Earl, as an adult, couldn’t remember much about his father’s banjo playing. Earl was given possession of his father’s open-back banjo at the age of four and began learning to play it immediately. He was so small, that in order to play the instrument he had to line up two chairs side-by-side, one for him and one for the banjo. He would sit in one chair and then place the head of the banjo on the chair to his right. Only in this unconventional seating arrangement could he reach the far left end of the fret board and still manage to pluck the strings near the center of the banjo’s head with his right hand. By the age of six, Earl was winning local banjo competitions. Before he was out of his teens he would be playing banjo professionally in a variety of country music groups.

Earl’s parents were members of the last generation of Americans who were likely to grow up hearing more live music than recorded music. In 1923, the year before Earl’s birth, only one percent of American homes had radios. By 1931, the number was 75 percent, and by 1937 virtually all American homes had radios in them. But Earl was raised in poverty. He grew up in a home that, during his early days at least, had no radio or gramophone. Nearly all the music he heard as a child was played live, usually by a relative or neighbor, if not by Earl himself.

When Earl took up the banjo, the most popular styles of playing the instrument were frailing and clawhammer, both of which involve brushing downward on the strings, usually with bare fingers. Those styles have evolved their own complexities and variations, but back then they were commonly associated with old-time folk and country music – sometimes called “string band music” – and tended to produce a slower and softer sound than the music that eventually came to be called bluegrass. Scruggs chose to play the banjo employing a method called “three-finger style,” and he eventually modified it and popularized it to such a degree that it is nowadays generally referred to as “Scruggs-style” banjo. If you go looking for online banjo lessons, the instructors (and they are legion) will specify whether they teach clawhammer style or Scruggs.

Plenty of gifted country musicians made their mark in the twentieth century, including the great Chet Atkins, a guitarist born just a few months after Scruggs, but almost none of them were so influential that the most popular method of playing their instrument – be it piano, guitar, drums, bass, fiddle, flute, or tuba – is now named after them. Jerry Lee Lewis on the piano, Chuck Berry on the guitar, Buddy Rich on the drums – these guys all expanded the range of what could be accomplished on their chosen instruments, but the most popular style of playing the piano isn’t called Lewis style. Only Scruggs changed the way his instrument was used so thoroughly as to become forever synonymous with the way most people now play it (clawhammer banjo, it should be noted, has enjoyed a resurgence in recent decades and is now nearly as popular as Scruggs style).

Earl always preferred picking a banjo to strumming it, a fact that caused his early audiences a great deal of amusement. In Thomas Goldsmith’s 2019 book, Earl Scruggs and Foggy Mountain Breakdown, the author quotes a Chapel Hill resident named Tom Burrus, whose mother was a schoolmate of young Earl Scruggs. Burrus notes that, “My mom told me a long time ago that when Earl Scruggs would play at talent shows in their school, many of the kids would just giggle at his ‘picking’ a banjo. I guess in her youth the banjo was supposed to be strummed.” In fact, the banjo, from its connection with the minstrel shows of the nineteenth century, was still widely regarded as a comic instrument when Earl was coming of age. Early in his career he was occasionally told that he would need to come up with a comic patter if he wanted to make a living as a banjo player. Audiences in the early twentieth century expected their banjo players to be joke-tellers as well as musicians. This tradition lasted well into the latter half of the century. On the popular TV variety show Hee Haw (1969-93), excellent banjo players such as Grandpa Jones and Roy Clark, would often combine comedy and banjo playing. So, too, did Steve Martin, during the days when he did stand-up comedy. Scruggs had a good sense of humor, but he had no desire to be a comedian. He was a serious musician and he brought to the banjo just as much artistry and skill as Yo-Yo Ma now brings to the cello. But unlike Ma, Scruggs had no formal training and he couldn’t read music. He played by ear, but he also tended to improvise a lot. Since sheet music was largely meaningless to him, he wasn’t prone to playing a song the same way every time. He liked to tinker with a tune, try out new things, keep the music fresh and his playing innovative.

Scruggs’s career as a professional musician didn’t truly take off until he joined Bill Monroe’s band The Blue Grass Boys in 1945. Just as Scruggs is often regarded as the father of three-finger banjo, Monroe is often referred to as the father of bluegrass music. Monroe, a mandolin player, named the band after the blue grass of his native state of Kentucky. Nowadays, many people think that bluegrass music has a long tradition going at least as far back as the 19th century. While it is true that bluegrass owes a great deal to various older musical traditions, the music that Bill Monroe and his band specialized in – combining speedy fiddle, guitar, and banjo instrumental work, high-voiced and somewhat nasally vocals and, occasionally, tenor harmonies – was pretty much invented by Monroe. Even today, many, if not most, bluegrass singers seem to imitate, to one degree or another, the vocal style of Bill Monroe. Monroe was a prickly character, often difficult to work with, and prone to exaggerating his own accomplishments and, occasionally, taking credit for other people’s. But it is nonetheless true that, more than any other person, he deserves credit for inventing what we now know as bluegrass music.

Lester Flatt, a gifted guitar player, left the Kentucky Pardners (a country band headed by Charlie Monroe, Bill’s brother) and joined The Blue Grass Boys shortly before Scruggs. Flatt and Scruggs were with The Blue Grass Boys for only three years but during that period the group pretty much defined what we now call bluegrass music, although Monroe was rarely inclined to give them any credit for it. Monroe’s band had earned a regular spot on the Grand Ole Opry’s weekly radio broadcast in 1939. The band was a sensation on the radio and a recording contract with RCA Victor soon followed. Monroe’s groups had always featured a guitar player or two, but his first banjo player, David “Stringbean” Akeman, was an old-timer in the minstrel tradition of the comedian/banjo player, and would later become a regular on Hee Haw (in 1973, he was brutally murdered, along with his wife, at the age of 58).

Akeman (pictured above) was a fine banjo player but no great innovator. When Akeman left The Blue Grass Boys, Flatt was pleased. He didn’t think the group needed a banjo player, and he was disappointed when he heard that Monroe was looking for a replacement for Akeman. But as soon as Flatt heard Scruggs’s playing, he told Monroe that he should hire the banjo player no matter what the cost. Flatt had never heard anything like Scrugg’s playing before. And not until Scruggs joined The Blue Grass Boys did Monroe’s band finally achieve the sound we nowadays call bluegrass music. As Wikipedia notes, “Scruggs played the banjo with a distinctive three-finger picking style that immediately caused a sensation among Opry audiences.” The Grand Ole Opry radio program wasn’t some staid and stodgy classical music program in which audience members are discourage from even coughing during a performance. Opry audiences in those early days commonly cheered and hooted when they liked what they were hearing. They were nearly as much a part of the program’s success as the musicians. Author Thomas Goldsmith writes, “When Scruggs started working with Monroe, he produced such a hard-hitting sound that audiences cheered for him like bettors at a prizefight, a reaction that can be heard on live recordings of the Opry.” He adds, “The live recordings that have circulated of the Blue Grass Boys during the Flatt and Scruggs tenure show the loud appreciation that Scruggs’s three-finger banjo work won on the Opry. In the close confines of the Ryman Auditorium, the savvy audience seemed to have an almost physical reaction to the driving music, and members whooped and yelled at Scruggs’s solos.”

Bluegrass musician Ricky Skaggs said that the notes flew from Scruggs’s banjo so rapidly that it “sounded like a computer.”

“When I first got here,” Scruggs told an interviewer, “Uncle Dave Macon [another Opry regular] was the big star, and he was a typical banjo player. He might play a little lick, but he used it more as a simple, rhythmic accompaniment. I made it a lead instrument. At the time there weren’t any other pickers like me, so it was all brand new. This new music was faster than what had come before, because I played really well on up-tempo tunes.”

Goldsmith notes, “The idea of a banjo as a lead instrument – to play hot improvised solos, as the fiddle and mandolin had been doing in the Blue Grass Boys – was brand new in country music, though Bob Wills and other Western swing musicians were already featuring ‘takeoff’ passages on fiddle, steel, and guitar.”

When people listen to Scruggs’s banjo playing, they often comment on his speed, and understandably so. But Scruggs always downplayed the importance of speed to his banjo style. In his own book, Earl Scruggs and the 5-String Banjo, he writes, “Early in my professional career, I was often referred to as ‘the world’s fastest banjo player.’ To me, that didn’t mean all that much. I have always been much more concerned with the tone of my playing and how I could pick so that each and every note can be heard clearly and cleanly, not how fast I could play those notes.”

According to musical historians Bill C. Malone and Jocelyn Neal, “When Earl Scruggs joined Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys in 1945, he brought with him a sensational technique that rejuvenated the five-string banjo, made his own name preeminent among country and folk musicians, and established bluegrass music as a national phenomenon.”

Playing with the Blue Grass Boys turned Earl into a country-music superstar, but neither he nor Flatt was ever very happy working with Monroe, who could be a tyrant at times. Flatt was a prolific songwriter, but in order to get Monroe to record any of his songs, Flatt had to agree to give the bandleader a co-writing credit. This cost Flatt a lot of money in royalties. (Monroe was not the only bandleader of the era who did this, and it can be at least partially justified by the fact that the leader often arranged the number and made alterations to it.) Scruggs was not as prolific a songwriter, but in 1947 he wrote a song called Blue Grass Breakdown. He played it for Monroe hoping that Monroe would want to record the tune and give Scruggs half the credit and half the songwriting royalties. “Well, I wrote Blue Grass Breakdown and thought he’d give me half of it,” Scruggs told Goldsmith in 2007. “He didn’t give me nothing.” Even fifty years later, Scruggs still nursed a grudge against Monroe for stealing Blue Grass Breakdown from him.

By 1948, Flatt and Scruggs were fed up with Bill Monroe and they left the Blue Grass Boys to form their own group. Monroe, out of spite, got them banned for a while from the Grand Ole Opry. It didn’t matter. For the next 21 years, Flatt and Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys would pretty much dominate the bluegrass music scene (The Soggy Bottom Boys, a fictional bluegrass group in the Coen Brothers’ 2000 film Oh, Brother, Where Art Thou, spoofs the name of the band). It happened almost immediately, with the recording of Foggy Mountain Breakdown on December 11, 1949. The song was written by Scruggs and the record was released in February of 1950. It has since become a standard and is played by nearly every bluegrass band in existence. Earl invented a brand new banjo roll (these are essentially eight-note picking patterns) for the song, which has since become a regular feature of banjo-playing. All the other major picking patterns have generically descriptive names – forward roll, backward roll, alternating roll, etc. – only the “Foggy Mountain” roll carries the name of the tune that originated it. Flatt and Scruggs re-recorded Foggy Mountain Breakdown in 1968, for Columbia Records, and earned a Grammy Award for their effort. The song has appeared on numerous movie soundtracks but is probably best known for appearing as background music in many of the scenes of the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway. Beatty, in his capacity as producer, chose the song for the film. It was an anachronistic choice, sort of like using music from Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in a film set in 1949. Bonny and Clyde takes place in the early 1930s at a time when bluegrass music didn’t exist and nobody anywhere was playing banjo the way that Scruggs played it on Foggy Mountain Breakdown. But Beatty was onto something. He recognized that, even if bluegrass music didn’t exist in 1934, it came from men who were alive at that time and it grew out of that Depression Era desire to break free of hard times and narrow cultural constraints. Rarely has an instrumental tune had so profound an effect on a Hollywood film. In Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood, film historian Mark Harris notes of co-screenwriters Robert Benton and David Newman, “They would work together in the night, with Flatt and Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys playing at full volume on the phonograph and becoming, in effect, the soundtrack to their experience of writing the movie.” (Benton and Newman intended for Francois Truffaut to direct Bonnie and Clyde, but he opted to make Fahrenheit 451 instead). Earl’s banjo music was mentioned in most of the film’s prominent reviews. In her positive assessment of the film, Pauline Kael noted that, by “emphasizing the absurdity with banjo music, they make the period seem even farther away than it is.” Longtime New York Times film reviewer Bosley Crowther effectively ended his career with the Times by publishing numerous attacks on Bonnie and Clyde. He objected to the way “mountain music” was used to add light-heartedness to a grisly tale of murder, “as if they were striving mightily to be the Beverly Hillbillies of next year.” In an interview, Beatty told Roger Ebert, “Bonnie and Clyde drive away in their touring car, and on the soundtrack we have Flatt and Scruggs playing ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown,’ giving the whole thing a kind of carnival air. Only this time the music isn’t appropriate, see? It’s music that says, laugh, but you can’t laugh. The whole movie kind of weaves back and forth between making you laugh and making you sick.” Scruggs’s song has a timelessness about it that would make it not out of place on the soundtrack of a movie western set in the 1870s. The marriage of Scruggs’s song and Arthur Penn’s film was so successful that it may well have inspired a less successful marriage that took place two years later. The anachronistic use of the song Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head, written for the film by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, in the 1969 George Roy Hill Western, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, struck a lot of people at the time (including co-star Robert Redford) as a mistake. The song is clearly a product of late-1960s flower-power era. To this day, the song tends to pull the viewer out of the film’s old west setting (Quentin Tarantino spoofed it when he inserted Jim Croce’s “I Got a Name” into his film Django Unchained). But Scruggs’s Foggy Mountain Breakdown, though anachronistic, has aged as well as the film Bonnie and Clyde itself. The success of Foggy Mountain Breakdown in Bonny and Clyde may also have inspired filmmaker John Boorman to use the 1955 tune “Dueling Banjos” in his 1972 film Deliverance. That marriage has also aged well.

During the 1950s, writes Goldman, “Scruggs’s fame spread as highly focused followers tried to learn his banjo style…His new compositions and techniques lit a beacon for others to follow as Scruggs, chiefly on his own, increased the world’s supply of five-string banjos and players.” In the mid 1950s, Flatt and Scruggs hired a Dobro player named Josh Graves. Impressed by Scruggs’s banjo playing, Graves became the first Dobro player to adopt the three-finger style to that instrument, and to employ hammer-ons and pull-offs the way that Scruggs did on the banjo. Nowadays, all Dobro players employ that method.

Not only did Scruggs contribute to the film culture of the 1960s, he contributed to the television of the era as well. During that brief era dubbed “Camelot” by the national press, when America was supposedly bewitched by the patrician airs of its Ivy League president and his glamorous wife, the nation’s most popular TV show was The Beverly Hillbillies (1962-71), which featured a family of unrefined Tennessee white trashians who regularly made fun of such airs (the press was always more bewitched by Camelot than were ordinary Americans). The program’s theme song, The Ballad of Jed Clampett, features the instrumental work of Flatt and Scruggs and is one of the most iconic themes in television history. The song was written by series creator Paul Henning and sung by Jerry Scoggins. The lyrics are mildly amusing and the tune is catchy, but the song doesn’t really become interesting until the singing ends and Scruggs’s banjo takes over. At that point it becomes a rousing crowd-pleaser. Flatt and Scruggs recorded a longer version of the song and released it as a solo record. It was their only song to reach number one on the Billboard Country chart. Along with Foggy Mountain Breakdown it is one of the songs that just about every bluegrass banjo player is expected to have in his repertoire. Flatt and Scruggs’s did more than just play the theme to The Beverly Hillbillies. They also appeared, as themselves, on seven episodes of the program. “Thrown into unlikely sitcom plots,” writes Thomas Goldsmith, “the real-life musicians came across as levelheaded country folk, not yokels.” The Clampetts were America’s anti-Kennedys, the antithesis of the know-it-all Harvard-educated elite, and Flatt and Scruggs were their troubadours. While east coast swells were listening to Richard Burton and Julie Andrews sing “What Do the Simple Folk Do?” the simple folk were watching The Beverly Hillbillies and listening to Earl Scruggs’s banjo. The Beverly Hillbillies struck a lot of purse-lipped critics as ridiculously far-fetched (see Ivy-Leaguer Bosley Crowther’s sneer above), but Goldsmith points out that Jed Clampett’s story wasn’t that different from, “the journey that Scruggs had made from nearly ‘starving out’ at Flint Hill to approaching the Hollywood dream of swimming pools and movie stars. Scruggs and partner Flatt had moved from backwoods obscurity to the front line. The tossed off description of Jed Clampett as a ‘poor mountaineer’ who could barely feed his family sounded poignant in light of the Scruggs family’s financial troubles after the death of George Elam Scruggs.”

Although they made great music together, Flatt and Scruggs had very different personalities. Flatt was ten years older than Scruggs and a rock-ribbed conservative. Scruggs was much more open to musical experimentation than Flatt. He wanted his music to always be evolving. In the 1960s he occasionally worked with Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and other fashionable folk singers. Flatt dismissed these collaborations as “hippie music.” In 1969, Scruggs joined thousands of others who were gathered at the Washington Monument to take part in a protest against the Vietnam War. He played Foggy Mountain Breakdown and other songs for the crowd. That may have been the last straw for Lester Flatt. The duo broke up in 1969. But the breakup was overshadowed by the breakup, a short time later, of a better-known musical act called The Beatles. Rock fans of the 1970s might not have realized it, but when they heard Bernie Leadon of the Eagles playing banjo on “Take It Easy” or The Who’s Pete Townsend playing it on “Squeeze Box,” they were listening to the influence of Earl Scruggs. Conversely, when they heard the song “In The Summertime,” by Mungo Jerry, they were listening to a tamer, pre-Scruggs style of banjo playing, one that involves strumming rather than picking.

Flatt died in 1979 at the age of 64. Scruggs lived on to the age of 88, dying on March 28, 2012. He had a profound influence on American popular music and particularly on the banjo players who came along after he first attained success. Foggy Mountain Breakdown has been selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Recording Registry. You’d be hard-pressed to find a musician whose influence on the way a particular instrument is played has been more profound than Scruggs’s influence on banjo playing. And, after Bill Monroe himself, probably no one had more to do with the birth and growth of bluegrass music than Earl Scruggs. Steve Martin has noted that, “It’s often said that Earl really defined that sound. Once Earl came in, that’s when it coalesced.”

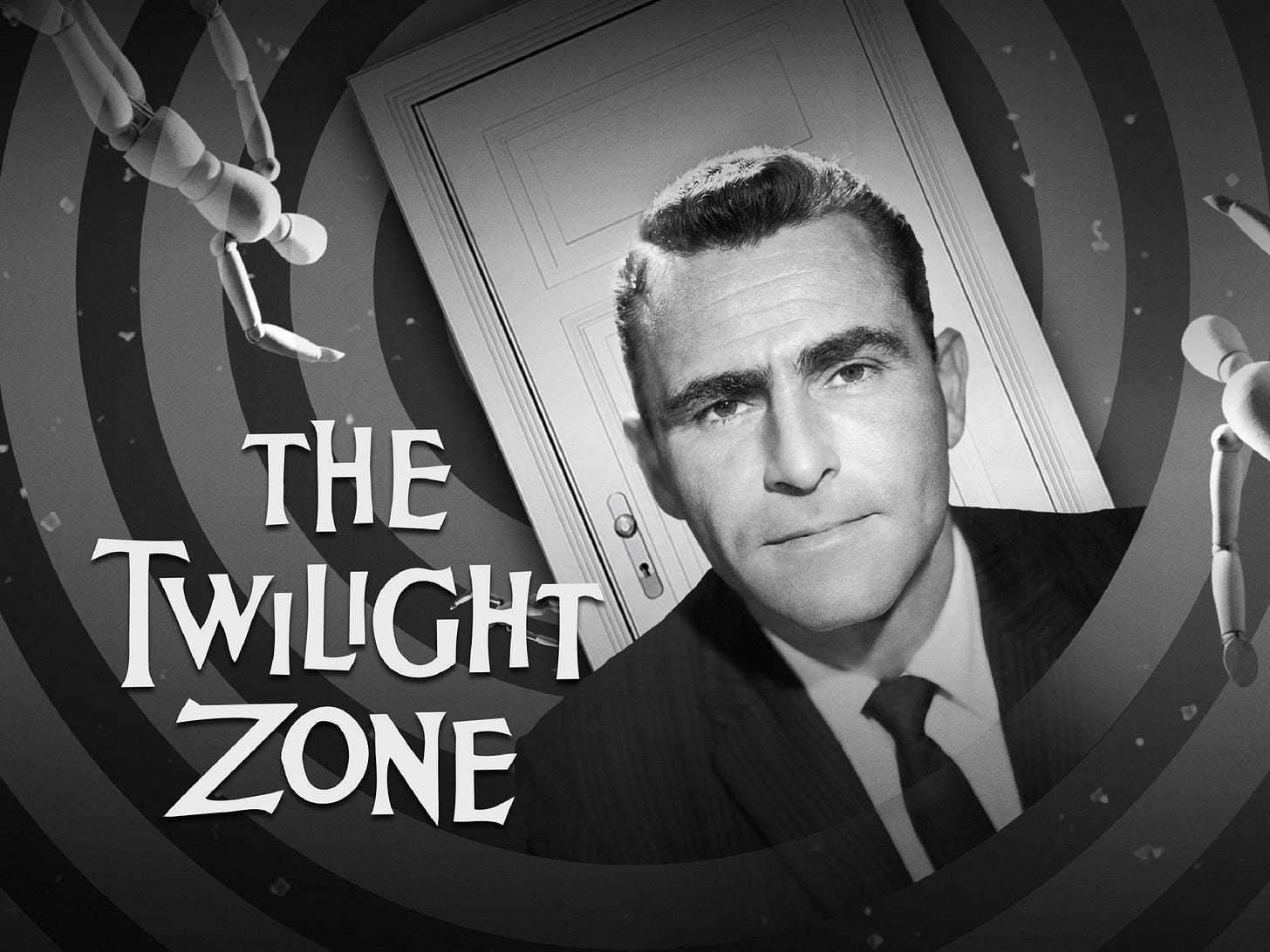

Another defining sound of the twentieth century was the opening theme of the Twilight Zone TV series. Although the series debuted in 1959, the iconic theme music wasn’t attached to the opening until the debut of the second season in September of 1960. It was probably the catchiest TV theme in America until, two years later, The Ballad of Jed Clampett came along. Writing in Slate, Matthew Dessem proclaimed, “The Theme from The Twilight Zone is one of the most easily recognizable pieces of music of the 20th century, a four-note motif for electric guitar with hair-raising dissonances that conjure up the uncanny and the unknown in an almost Pvlovian way. Its creepy-crawly charm transcends all cultural barriers…”

The Twilight Zone was the brainchild of Rod Serling, another pop-culture phenomenon born in 1924. Serling was born on Christmas Day (43 days before the birth of French composer Marius Constant, who composed the Twilight Zone theme) in Syracuse, New York, and grew up in Binghamton, New York, just north of the Pennsylvania state line. Serling’s upbringing in small-town America informs much of his work, including many of the 92 episodes (out of a total of 156) that he wrote for The Twilight Zone. Serling was a Jew in a largely Christian community, and a sense of outsiderness also permeates much of his work. But Binghamton wasn’t the first U.S. city to enter the Twilight Zone. That honor belonged to Cincinnati, Ohio. After military service and college, Serling moved to Cincinnati in 1950 to take a job with radio station WLW-AM as a continuity writer. His writing for WLW – advertising copy, news briefs, local color – was largely unfulfilling for him. He longed to write fiction, especially weird stories, combining elements of the occult, science-fiction, nostalgia for small-town America, and melodrama. He got his chance to do just that when WKRC-TV, a rival media outlet, began broadcasting its own weekly anthology series, a program called The Storm. Because he was still under contract with WLW, he submitted scripts to The Storm under the name R. Edward Sterling (his birth name was Rodman Edward Serling, but people were forever mispronouncing his last name, and Sterling does have a classy ring to it). His first script for The Storm was “Keeper of the Chair,” the story of a prison guard who fears he is being haunted by all the condemned men whose executions he has witnessed. Serling biographer Nicholas Parisi notes that, “With a protagonist whose senses and memories have become unreliable, a one-step-from-reality tone, and a twist ending, ‘Keeper of the Chair’ could be considered Rod Serling’s first Twilight Zone story produced on television.” “The Time Element,” another story written for The Storm, was later reworked by Serling and broadcast as an episode of Desilu Playhouse on November 10, 1958. Serling was actively developing The Twilight Zone at the time and “The Time Element” (originally titled “Twilight Zone – The Time Element”), “is now considered The Twilight Zone’s first pilot,” writes Parisi. He adds, “Viewers in Cincinnati did not know it, but they had entered The Twilight Zone seven years earlier than the rest of the country.” TV writer Mark Dawidziak believes that the Cincinnati years were crucial to Serling’s development. “Without Cincinnati,” he writes, “you don’t get to the next level of Rod Serling. He took all his experiences – growing up in Binghamton, his war experiences, his college experiences – and worked through them in Cincinnati. Cincinnati is the door that leads to everything else.” Serling wrote 32 episodes of The Storm, most of which are now lost. But even before he began selling scripts to The Storm, Serling had sold several stories to a national TV program called Stars Over Hollywood. The first of these, “Grady Everett for the People,” was broadcast on September 13, 1950. It was Serling’s first sale to a national TV program and it appeared in the same year that Foggy Mountain Breakdown was released on vinyl. Scruggs wrote and recorded Foggy Mountain Breakdown in 1949, and that was also a big year for Serling. In Serling: The Rise and Twilight of Television’s Last Angry Man, biographer Gordon F. Sander notes that, “Rod Serling got his first euphoric taste of national fame on the evening of May 18, 1949, when he appeared at the New York studios of The Dr. Christian Show to accept his third-prize scriptwriting check for five hundred dollars from Jean Hersholt, the program’s genial Danish host.”

Unlike Earl Scruggs, whose family was too poor to own a radio when he was a small boy, Serling was practically raised on radio. Casual fans of Serling’s probably assume that his interest in weird tales was nurtured in his youth by the reading of stories by Edgar Allan Poe, Jules Verne, H.P. Lovecraft, H.G. Wells, and other early writers of horror, sci-fi, and fantasy fiction. Rod had a lifelong fondness for reading, but he was born into the dawning of the age of radio, and radio was his first love. The first commercial radio broadcast in the U.S came from station KDKA, on November 2, 1920. KDKA was located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, about 400 miles from Serling’s hometown. By the time Rod was born, in 1924, more than 600 commercial radio stations were operating across the U.S. Rod’s earliest literary role models were radio scriptwriters. Among these were Wyllis Cooper, the creator of a radio anthology series called Lights Out! The program, which featured stories in a variety of genres – crime, fantasy, horror, etc. – debuted in 1933, when Serling was eight, and eventually became popular enough to inspire 600 fan clubs across the country. In 1938, a burnt-out Cooper left the program and was replaced by Arch Oboler, at which point the show became both funnier and darker. Oboler’s scriptwriting, like Cooper’s, was in high demand during the 1930s. Wikipedia notes: “Oboler met the demand by adopting an unusual scripting procedure: He would lie in bed at night, smoke cigarettes, and improvise into a Dictaphone, acting out every line of the play. In this way, he was able to complete a script quickly, sometimes in as little as 30 minutes, though he might take as long as three or four hours. In the morning, a stenographer would type up the recording for Oboler's revisions. Years later, Rod Serling, who counted radio fantasists like Cooper, Oboler, and Norman Corwin among his inspirations, would use a similar process to churn out his many teleplays for The Twilight Zone, a series that in many respects was to television what Lights Out was to radio.” It was easier for Serling to talk-out a story than to write it out by hand because that was how he had absorbed so much of the fiction he consumed as a child – aurally. Just as Earl Scruggs could write songs without being able to read sheet music, Serling could write stories without having to put anything down on paper.

Serling, along with filmmaker Francois Truffaut, was also a big fan of Oboler’s later film work. Oboler’s 1951 film, Five, is a post-apocalypse tale set in Malibu, California. The film came along just as Serling was beginning to write for radio, and it may well have influenced the script he later wrote for The Planet of the Apes, another dystopian story.

Norman Corwin (1910-2011, and pictured above) is widely regarded as the first prominent radio scriptwriter to put social issues at the heart of nearly all his stories. He was a huge influence not just on Serling but on many of Serling’s contemporaries and colleagues: Norman Lear, Ray Bradbury, Robert Altman, and Gene Roddenberry, to name but a few. Corwin did some of his best work for a radio anthology series called Columbia Workshop, which aired on CBS from 1936-1943. One of his most famous scripts for Columbia Workshop, “The Plot to Overthrow Christmas,” was a fantasy tale in which Mephistopheles conspires with other denizens of Hell to assassinate Santa Claus. It appears to have had a profound influence on Serling. Though he was Jewish, Christmas (his own birthday) was a particular obsession of Serling’s and is featured in many of his stories.

It seems almost certain that he was a fan of Corwin’s dark Christmas fable, which would have worked well as a Twilight Zone episode. So important was Corwin’s work to Serling that, in 1949, after winning that third-place award for screenwriting, he gushed to a friend, “I felt like Norman Corwin!” Not Poe, not Hemingway, not Dickens, but Norman Corwin was Serling’s beau ideal of a successful writer. (Arch Oboler, by the way, was one of the judges on the panel that awarded the prizes.)

As a fan of eerie radio programs, Serling would have been familiar with The Shadow, which debuted in 1937 and featured the voice of 22-year-old Orson Welles, who played the titular character (much later, CBS tried to hire Welles to introduce the episodes of The Twilight Zone, but he wanted too much money, so Serling was allowed to do it himself). The Shadow was created by pulpsmith Walter B. Gibson. Like Oboler and Cooper and many of Serling’s other early role models, Gibson could turn out a vast amount of material steadily and reliably. Here’s Wikipedia again: “Described as a ‘compulsive writer,’ Gibson is estimated to have written, at his peak output, 1,680,000 words a year and at least 283 of the 336 Shadow novels. Gibson ultimately contributed more than 15,000,000 words toward Shadow publications.” That kind of productivity may explain why, in the 1960s, Gibson was chosen to write prose adaptations of Twilight Zone scripts, which were collected in books with titles such as Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone Revisted and Chilling Stories From Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone. Thus, the man who invented The Shadow became, for a while, Serling’s literary shadow. Serling himself wrote several collections of tales adapted from both The Twilight Zone and The Night Gallery, a later anthology series which he hosted and wrote for (he was nowhere near as involved in the daily production of The Night Gallery as he had been in The Twilight Zone). Between these two programs he also created a short-lived Western TV series called The Loner. Its 26 episodes aired between September, 1965, and March, 1966, and Serling wrote fifteen of them. He also published three original novellas in a 1967 book called The Season to Be Wary, which he dedicated to his friend Sammy Davis Jr., who had suggested the idea for one of the stories. Serling may not have been as insanely prolific as Gibson, but he churned out an impressive number of scripts over the course of his career. Probably the most complete inventory of this output can be found in Nicholas Parisi’s Rod Serling: His Life, Work, and Imagination. Appendix D of that book lists every screenplay, teleplay, and radio play, that Serling is known to have written (although some of these are now lost). I didn’t count them all up, but the list of these writings contains about 25 titles per page and runs for twelve pages, for an approximate total of 300 scripts. But Serling’s contribution to popular culture cannot be defined by mere numbers. He gave us a term – twilight zone – that we didn’t know we needed until we had it. It describes a liminal space between reality and fantasy, fact and fiction, consciousness and the subconscious, light and dark, dream and nightmare, or any other two seemingly opposing ideas. In the sixty-five years since the TV series debuted, plenty of others have tried to create a similar term, but none of them have had the cultural impact of twilight zone. The title of Stephen King’s book The Dead Zone tries to capture a bit of Serling’s ambiguity but doesn’t really cut it. King often seems to be straining to find a term as indelible as twilight zone. His books are full of places known as “the territories,” “the outposts,” “the blasted lands,” “the Free Zone,” “In-World,” “Mid-World,” and so forth. He is also fond of titles such as “Just After Sunset” and “The Dark Half” and “Four Past Midnight” and “End of Watch” and “Night Shift” that suggest a borderland between light and dark, which is essentially what twilight zone means. King’s impact on popular culture has been much larger than Serling’s, but he hasn’t ever coined a phrase as necessary as twilight zone, despite countless efforts.

In his role as the host of The Twilight Zone (the role was first offered to Orson Welles but he wanted too much money), Serling created one of the most iconic characters of 1960s television. He also introduced the segments of The Night Gallery. He was the executive producer of The Twilight Zone and gathered one of the most impressive team of fantasy and sci-fi writers ever to work for television – Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, Earl Hamner Jr., George Clayton Johnson, and, of course, Serling himself, all of them born in the 1920s. Almost all of the members of his writing team were recommended to Serling by Ray Bradbury (who contributed only a single script to TZ). Bradbury served somewhat the same role in Serling’s life that Bill Monroe served in Scruggs’s. He was both an inspiration of sorts to Serling and also a frenemy. Bradbury made a name for himself as an author of weird tales well before Serling did. Serling was a fan of Bradbury’s fiction and Bradbury a fan of Serling’s TV work. In coming up with the term Twilight Zone, Serling may have been inspired by the title of Bradbury’s 1955 story collection, The October Country, which Bradbury defined as, “That country where it is always turning late in the year. That country where the hills are fog and the rivers are mist; where noons go quickly, dusks and twilights linger, and midnights stay.” In 1959, as Serling was preparing TZ for its debut, Bradbury was trying to get a pilot made for a program called Ray Bradbury’s Report From Space. Bradbury’s program never got made, and Serling’s became iconic, a fact that seems to have rankled Bradbury. A year after Serling’s TZ teleplay “Where Is Everybody?” aired on October 2, 1959, Bradbury began complaining to friends that Serling had plagiarized his own 1949 short story “The Silent Towns.” Scholar Amy Boyle Johnston thoroughly discredits this notion in her monograph “Unknown Serling.” Bradbury’s story is set on Mars and features a human colonist, Walter Gripp, who wanders into an abandoned town. Serling’s story concerns an American serviceman, Mike Ferris, who wanders into a small town and finds it abandoned. The similarities end quickly. Gripp knows why the town is empty and he soon finds another living colonist. Ferris is actually unconscious and undergoing a military experiment in sensory deprivation. Both stories could be said to have derived from Mary Shelley’s 1826 novel The Last Man and, indeed, Serling’s story indirectly references it when Mike Ferris finds a bookrack full of copies of a novel titled The Last Man on Earth. Nonetheless, Bradbury began to spread the tale to mutual acquaintances that Serling had plagiarized his work. Serling got so angry that he wrote to Bradbury, called him “a back-biting accuser,” and dared him to take his complaint to court. Bradbury had successfully sued other writers whom he thought had stolen his work, but he never sued Serling. Later Serling was accused of plagiarizing Bradbury’s story “Black Ferris” for his teleplay “Walking Distance.” Amy Boyle Johnston ably refutes this charge as well. Despite the hostility between them, the men were capable of being civil to each other. In fact, in 1960, the Serling and Bradbury families drove to a science-fiction convention in Seattle together, where Serling was to be presented with an award for his TZ work (Bradbury never acquired a driver license and refused to fly, so he frequently freeloaded rides from his friends and acquaintances whom, he assumed, would be honored to ferry the great man about). Just as Bill Monroe seemed to resent anyone else who could lay claim to being a major force in the creation of bluegrass, Bradbury at times seem to resent hearing anyone else being heralded as an American master of the post-war weird story. He helped nurture some of these other masters – Matheson, Beaumont, etc. – so he didn’t mind it too much when they received praise. But Bradbury had no direct involvement in Serling’s rise to stardom, and he didn’t handle it well when TZ almost instantly made Serling America’s new King of the Weird Story. In later years, Bradbury got prickly when asked about TZ. In 1980, he told an interviewer, “I would prefer not to talk about Twilight Zone or my stories. The series is over and done, my work stands on its own.” That comment seems to suggest that TZ had faded into obscurity. But that, of course, was utter nonsense in 1980, and remains utter nonsense forty-four years later.

Back in the 1960s, even people who couldn’t name one other TV scriptwriter probably knew the name Rod Serling, just as people who couldn’t name one other banjo player probably knew the name Earl Scruggs. It’s difficult to exaggerate the influence that both The Beverly Hillbillies and Twilight Zone had on the baby-boom generation. Both programs are frequently used as shorthand between boomers to describe certain types of people and/or situations. A typical example of this can be seen in Ice Cold, a 2010 thriller written by novelist Tess Gerritsen (born 1953). On page 41, one character describes a small-town shop to another like this: “That was like a time capsule. Did you see those Pez dispensers? They had to be twenty years old. And that old guy behind the counter was like some character out of The Twilight Zone.” Later, on page 83, when two characters are discussing some hicks they have recently encountered, we get this exchange:

“Wait, wait. I’m getting a mental picture of these people.” Arlo pressed his fingers to his temples and closed his eyes like a swami conjuring up visions. “I’m seeing…”

“American Gothic!” Doug tossed out.

“No, Beverly Hillbillies!” Elaine said.

“Hey, Ma,” Arlo drawled, “pass me another helping of that there squirrel stew.”

To this day, whenever my wife serves spare ribs for dinner, she always assures me that she cooked them until they were “fallin’ off the bones tender,” a line she got from Granny on the Beverly Hillbillies, who once asked a dinner guest, “How do you like yer possum, Lowell, fallin' off the bones tender or with a little fight left in it?” Likewise, I’ve lost track of all the times fellow boomers have told me I remind them of Henry Bemis, a bookworm (played by Burgess Meredith) in the classic TZ episode called “Time Enough at Last” whose love for reading is so passionate that it has blighted both his career as a bank teller and his marriage (I hope I’m not quite that bad, but…).

Due to difficulties in finding a sponsor, the fourth season of Twilight Zone (the article “The” was dropped after season three, for some reason) didn’t begin airing until midway through the 1962-63 season. Both The Beverly Hillbillies and The Twilight Zone aired on CBS TV. And the first week of January, 1963, was the first time both programs aired together in Prime Time. An episode of The Beverly Hillbillies entitled “Jed Rescues Pearl” aired on January 2, 1963. The next evening, Twilight Zone’s fourth season debuted with an episode entitled “In His Image,” which is credited to writer Charles Beaumont (he was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease by this time and, reportedly, several of his friends ghostwrote scripts for him in order to keep his family afloat financially). In any case, the first week of 1963 was the first time American TV viewers were offered a heapin’ helping of Earl Scruggs and Rod Serling on back-to-back evenings. Twilight Zone was nearing the end of its five-year run on CBS, but it would return in syndicated reruns up until the present day. And new iterations of it – a monthly magazine, several novelizations, a reboot of the TV series, a feature film, a radio series, etc. – would keep the franchise healthy for decades to come. Unfortunately for Serling, he sold his interest in The Twilight Zone to CBS after it was cancelled. The price was reportedly very low. Serling, whose work often looked into the future, failed to see just how lucrative the syndication market was going to be for The Twilight Zone. Nor did he anticipate the huge market for spin-offs and ancillary products.

Alas, Serling was a demon-haunted man. During World War II he fought as an infantryman in the Battle of Leyte, an island in the Philippines. He got his training with hundreds of other enlistees at Camp Toccoa, in Georgia, home of the U.S. Military’s Eleventh Airborne Division. From there he became a member of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment. After Leyte, his regiment was sent to help General Douglas McArthur’s troops liberate Manila. During these final battles for the Philippines, Serling shot and killed Japanese soldiers, and saw plenty of his own fellow soldiers killed. He was particularly haunted by an occasion where he shot and killed a Japanese soldier who was standing on third base of the baseball field at Manila’s Rizal Stadium. It was an almost Twilight-Zone-like experience, killing someone on a field meant for a friendly game of America’s favorite pastime. Rod was injured by shrapnel from an enemy anti-aircraft gun. He was sent to New Guinea to convalesce, but he soon returned to Manila for more combat. According to biographer Gordon F. Sander, “By the time Japan finally sued for peace on August, 6, 1945, only 30 percent of the original members of the regiment from Camp Toccoa were still alive. Then, on that same day, came the final piece of shrapnel: the telegram informing Serling of the death of his father, of a heart attack, at the age of fifty-five.” Another TZ-like twist. For his military service, Serling earned a number of awards, including a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart.

In a way, Serling’s whole life was about liminal states and twilight zones. He was born in an era that is often referred to as “the interwar period” because it fell between World Wars One and Two. He was also born into the age of radio, which fell somewhere between the birth of cinema and the birth of television. He had homes near America’s east coast and its west coast, and shuttled between them frequently. The fight for racial equality was important to him in part because, as a Jew, he stood somewhere between the country’s white Gentile majority and its black minority. He stood only five-feet-four-inches tall, but he had a big voice and a powerful presence.

It seems clear that Serling came home from the war suffering from what we now call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, although the diagnosis didn’t exist at the time. He would suffer from war-related nightmares for the rest of his life. He came home from the service bitter and angry. By then he had become a fairly heavy drinker and an even heavier smoker, consuming sixty or more cigarettes a day for the rest of his life. For the most part he was able to fight off his mental demons by burying himself in work. After returning from the Philippines, he enrolled in Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, mainly because it was his older brother, Robert’s, alma mater. He joined the Unitarian church and married his college sweetheart Carolyn Kramer in 1948. Rod’s family was distressed that he had married a gentile; Carol’s that she had married a Jew. Rod’s family eventually warmed up to his new bride. Carol’s father, an anti-Semite, never accepted his new son-in-law. Most of the rest of her family disowned her as well. Rod’s chief interest during his time at Antioch was working for the campus radio station, the grand-in-name-only Antioch Broadcasting System. “Each week, he would write an original dramatic script or adaptation, direct it, and often act in it himself...” writes Sander. “At ABS, Serling was the star of his own one-man show, as he would be years later with The Twilight Zone, and he loved it.” He graduated with a B.A. in Literature in 1950. After graduation, he earned some extra money by testing parachutes and ejector seats for the Air Force. At one point he was paid a thousand dollars for testing an ejection seat that had already killed three previous test subjects, another experience that might have left him a bit demon-haunted.

By the mid 1950s, Rod had moved his family (he and Carol had two daughters by then) to New York City and he had become a prolific writer of mostly unremarkable television fare. But in 1955 he wrote a TV play called Patterns, about corporate infighting, for Kraft Television Theater. It was broadcast live on January 12 and became an instant sensation. New York Times reviewer Jack Gould wrote, “Nothing in months has excited the television industry as much as the Kraft Television Theatre's production of Patterns, an original play by Rod Serling. The enthusiasm is justified. In writing, acting and direction, Patterns will stand as one of the high points in the TV medium's evolution.” The script earned Serling the first of six Emmy Awards he would receive over the course of his career. Patterns proved so popular that another live broadcast of it was made on February 9, the first time ever that a TV drama had been repeated. You could argue that Rod Serling invented the TV rerun. The following year Patterns was adapted for the big screen. That too was a critical success.

After Patterns, Serling became one of TV’s most sought-after writers and turned out a long stream of successful dramas, most notably Requiem for a Heavyweight, which was broadcast on Playhouse 90 on October 11, 1956, and would later be adapted for British television (where it starred Sean Connery), Dutch television, Yugoslav television, Italian television, American cinema, and even the Broadway stage. By 1959, Serling was probably the only TV writer in America with enough clout to get a major network to back a project as weird as The Twilight Zone. Alas, though the show, like Star Trek, became a phenomenon after the original series was cancelled, The Twilight Zone was only a modest hit during its original run. Serling, an avowed lifelong liberal, wanted to use the program as a platform for his views about social justice, particularly racial justice and civil rights. And he often did manage to sneak a great deal of political commentary into The Twilight Zone, albeit in an oblique fashion. But because the program wasn’t a ratings juggernaut like The Beverly Hillbillies, Serling spent much of his time battling with network censors, network executives, and even sponsoring advertisers. By the time the program was cancelled (the final original episode aired on June 19, 1964), Serling was more or less sick of it, which may explain why he gave up his interest in the program so casually.

Rod Serling remained very active after Twilight Zone ended but he was never again as culturally prominent as he had been from 1955-1964. During his heyday, he was constantly battling with TV advertisers, and calling the actors and writers who worked in advertising “whores.” But after TZ went off the air, Serling became one of the busiest whores in the business. In a loving memoir called As I Knew Him: My Dad, Rod Serling, Anne Serling writes (in present tense) of her father’s descent into commercial degradation: “He…continues to do commercial spots (Anacin, the bug spray called 6-12, a car wax, and beer). The irony of this is never lost on him. He is profiting from the sponsors he battled for so long in his early days of writing. I remember my parents discussing this, even arguing. I remember my mother telling him he needs to investigate the things that he is trying to sell to the public, and his acknowledging this, but commenting on how ludicrous it was that by recording a sixty-second television spot he can make more money than he can writing. Or, as he told his media class at Antioch, ‘I get $3,000 to make beer commercials and the same amount to teach for six months.’” His frequent appearances in print and TV commercials drew angry letters from fans who accused him of selling out his integrity. He didn’t bother to disagree. Having surrendered his interest in TZ, he needed all the money he could scrape together. He must have sensed that he’d be departing this world soon and didn’t want to leave his family financially strapped. He was briefly eclipsed in the public sphere by his older brother, novelist Robert J. Serling, whose 1967 thriller, The President’s Plane Is Missing, spent 22 weeks on the New York Times Bestseller list. Though Robert was a conservative Republican, the brothers were close and collaborated on a few projects. Robert’s fiction often contains passages that sound like they might have come from one of Rod’s TZ intros:

“Most of all, the stewardesses think of Rebel on dark, lonely nights, when strange creaks seem like the lurking of steps of an unseen invader and when imagination distorts every shadow and sound into terror.”

“Like all pilots, he hated and dreaded the fog. An insidious, malevolent killer, its very silence the epitome of lurking death.”

In fact, the writing of both brothers frequently resembles the narration in a Depression Era radio melodrama. In his 1977 crime novel, McDermott’s Sky, one of Robert’s characters is cleared of a murder charge when he accurately recalls for the police the plot of an episode of The Night Gallery that he was watching at the time that the murder was being committed (a plot point that would not have worked a few years later, after the widespread availability of videotape made it possible to watch network TV shows whenever you wanted to). Robert clearly was very fond of his more famous, younger brother.

Rod Serling died of a heart attack on May 3, 1975, at the age of fifty, after years of heavy smoking and breathing problems. His legacy, since then, has grown exponentially. His wife, Carol, lived to be 90, and died in 2020. His brother lived to the age of 92 and died in 2010. But neither of them had seen the horrors of war that would, throughout his life, impel Rod to live and work as if Death itself were dogging his footsteps, as, in deed, it was. Earl Scruggs, because his father was dead and his mother depended on her children to run the family farm, was exempted from military service during World War II. It was one of the few times that poverty worked in his favor.

A lot of prominent Americans were born in 1924 – drummer Max roach, astronaut Deke Slayton, actor Lee Marvin, jazz singer Sarah Vaughan, Marlon Brando, Henry Mancini, President George H.W. Bush, President Jimmy Carter, filmmaker Sidney Lumet, James Baldwin, jazz singer Dinah Washington, actress Lauren Bacall, author Truman Capote, Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist, hack filmmaker Ed Wood, actress Cicely Tyson – but Scruggs was the first American born that year who would go on to some form of superstardom, and Serling was the last. And no amount of fog or twilight seems likely to dim their legacies any time soon.

Great article about how the rural and urban members of the Greatest Generation made their mark on our culture in the post war years.