LET US NOW PRAISE JILLIANE HOFFMAN

Dexter Morgan, the main character of a prestigious Showtime TV series and, before that, a series of books by author Jeff Lindsay, is probably the most famous of South Florida’s fictional serial killers, but he isn’t the only Miami mass murderer in contemporary pop culture whose exploits are worth seeking out. In 2004, the same year in which Lindsay published the first of his Dexter novels (Darkly Dreaming Dexter), Jilliane Hoffman, a former public prosecutor in Miami, published the first of her legal thrillers, a novel called Retribution, which featured a serial killer known as Cupid (he cuts out the hearts of his victims, who are all young and attractive blonde women he picks up at singles bars). The main character in Retribution is C.J. Townsend, a public prosecutor in Miami. In 1988, when she was a young law student in New York City, C.J., then known as Chloe Larson, was brutally raped and left near death by an attacker who was never caught (he was wearing a clown mask during the attack and Chloe can’t give much of a description of him). Now, twelve years later, in 2000, she has changed her name, her appearance, and her location, but she certainly hasn’t put the rape behind her. It still haunts her, making it difficult for her to put together much of a social life, and it is also what drives her to put criminals behind bars. Early in the year 2000, a man named William Bantling is pulled over for a traffic stop on a Miami freeway. The police seem to suspect Bantling of driving under the influence of marijuana. They ask him if they can search the trunk of his car. He refuses. They request that a K9 unit be sent to the scene. When a drug-sniffing dog seems to catch a whiff of some contraband substance in the trunk of the car, the officers now have probable cause to search the trunk. They open it up and find the dead body of a beautiful young blonde woman whose heart has been cut out of her chest. And just like that, it looks like the police have stumbled onto the identity of the serial killer who has eluded them for months. C.J., one of the top prosecutors at the State Attorney’s Office, is assigned to handle the prosecution of Bantling. When she shows up for Bantling’s first appearance in court, she hears him talking and instantly recognizes his voice as that of the man who raped her twelve years earlier. At that point, prudence and her professional code of ethics obligate C.J. to withdraw from the case. But she doesn’t. She worries that some lesser prosecutor might botch the case and allow Bantling to walk. And so she makes the fateful decision to keep her own horrible history with Bantling a secret and maintain her role as lead prosecutor. She assumes that Bantling will never connect her with the scared young woman named Chloe Larson whom he raped and assaulted years earlier in New York City. Alas, she is wrong about that.

Retribution is one of the best legal thrillers published in this country since Scott Turow’s Presumed Innocent kicked off the current vogue for legal thrillers way back in 1987. In fact, Retribution strikes me as much better than both Presumed Innocent and John Grisham’s The Firm, another of the founding texts in the current legal-thriller vogue (which, by now, is much more than a vogue; it is a staple of American popular fiction). The recently departed Nelson DeMille, a master of the thriller genre, called Jilliane Hoffman “One of the best legal thriller writers in the country.” He added, “Retribution was the finest courtroom drama I’ve read in years.”

Retribution is full of fascinating legal details. I always assumed that both sides in a criminal case were required to provide disclosure to each other. But apparently that is not always true. In some jurisdictions – including Florida, apparently – a defense attorney can request permission to refuse to accept disclosure documents from the prosecution. “Why on earth,” I wondered, “would a defense attorney not want to know every bit of incriminating evidence the prosecutor has against the defendant?” Well, it turns out that, by refusing to accept disclosure materials from the prosecutor, the defense attorney can avoid the requirement of disclosing to the prosecutor materials crucial to the defense. If, for instance, the defendant has a solid alibi for the time of the murder, he may not want to disclose it to the prosecutor in advance, thus denying the prosecutor a chance to poke holes in it. Waiving the right to disclosure isn’t always that damaging to the defense, because even when disclosure is waived, the prosecutor has a constitutional obligation to disclose so-called Brady material – i.e., evidence favorable to the defendant – to the defense attorney. So, when disclosure is waived, the defense attorney still gets Brady material while the prosecutor gets bupkis. None of this is likely to surprise anyone with a law degree (the Brady material law dates back to 1963), but I found it fascinating. And Hoffman doesn’t throw this information out there at random. It is pivotal to the story she is telling. Bantling eventually figures out that C.J. Townsend is the woman he raped twelve years earlier. He and his attorney don’t want to disclose this information to the prosecutor. They plan to withhold it and, if the defense seems to be faltering late in the trial, release the information in order to suggest that C.J. is pursuing a malicious prosecution against Bantling in violation of the State Attorney’s Office’s own ethics regulations. All of this makes for a fascinating game of chess between C.J. and defense attorney Lourdes Rubio.

Elsewhere in the novel we learn that the state of New York has a statute of limitations of five years on all crimes except murder. This is why C.J. can’t simply come forward and identify Bantling as her rapist and have him sent back to New York to stand trial for the crime. After a crime (other than murder) is committed in New York, prosecutors have five years to identify a suspect and charge him or else the case will be unpursuable. But, even if the suspect remains at large for five years, the statute of limitations can’t protect him if he has been identified and charged in court with the crime within that period. Hoffman notes that prosecutors around the country have come up with a novel way of skirting the statute of limitations when they don’t know the identity of the criminal. In rape cases, where DNA evidence is often available, prosecutors, when the five-year deadline is approaching, will often file charges against the unknown rapist not by name but by his DNA profile. Courts, according to Hoffman, have held that this is an acceptable way of identifying a defendant. After all, hundreds of people probably have a name like Ronnie Jackson or Michael White, but no two people (excluding identical twins) have the same DNA profile. I had never heard of the practice of filing charges against a DNA profile, so I was fascinated by Hoffman’s discussion of the practice. If my summary of the practice is flawed, blame me and not Hoffman. I probably haven’t done justice to her explication of all the fine legal details at play here.

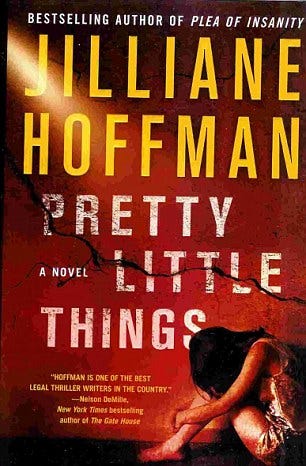

Retribution had some of the flaws often found in first novels – schmaltzy writing, clichés, etc. – but a lot fewer than most freshman efforts contain. After reading the novel, I went back to J. Crawford Books in Sacramento (where I bought Retribution) and purchased a copy of Hoffman’s 2010 thriller Pretty Little Things. This is the story of thirteen-year-old Lainey Emerson, who is abducted by a murderous pervert who stalks her online and, under the guise of an attractive high school athlete, catfishes her into meeting him alone one night in a secluded spot. Lainey is just the latest victim of a serial killer whom the police have dubbed Picasso because, before killing his underage victims, he paints a portrait of them and then sends it, through a circuitous route, to the authorities. The material might be off-putting to a lot of readers, but I was practically raised on the pop fiction of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, when children-in-jeopardy novels were as popular as legal thrillers are nowadays. Mary Higgins Clark’s Where Are The Children?, John Saul’s Suffer the Children, Robert R. McCammon’s Mine, just about anything written by Gloria Murphy or V.C. Andrews – thanks in part to the so-called “satanic panic” of the era and media sensations such as the bogus McMartin preschool scandal, novels about children being menaced by killers, rapists, and various crazy people were all the rage for much of my teens and twenties, and I devoured tons of them.

Alas, after acquiring, through marriage, two young stepdaughters and, later, many grandchildren, I lost much (but not all) of my enthusiasm for tales about little children in grave danger. Last year I mentioned, in a review of Tess Gerritsen’s excellent novel Harvest, that I tend to shy away from scenes in films and books that involve the mistreatment of children and animals. Fortunately, like many of the best books in the children-in-jeopardy genre, Pretty Little Things focuses primarily on the attempt by law-enforcement professionals to find and rescue the missing child and not so much on the abuse that she receives at the hands of her abductor. Though it was published long after the heyday of the genre, Hoffman’s Pretty Little Things is one of the genre’s best entries, an intelligent and genuinely thrilling race against the clock to rescue one of south Florida’s “disposable children,” kids who are so neglected that even their own parents don’t both to report their disappearances until they’ve been missing for days or weeks.

Pretty Little Things is not a legal thriller; the main character is Florida Department of Law Enforcement Special Agent Bobby Dees, an expert at investigating crimes against children. Nonetheless, the novel, like Retribution, contains a lot of fascinating legal questions. At one point, a task force headed by Bobby Dees visits the home of a man they suspect may be involved in Lainey’s disappearance. The man is away from home. The police would like to search his house but time is of the essence and they don’t want to wait for a warrant. They ask the suspect’s wife for permission to search the house. Reluctantly, she grants it. At the back of the house, the police find a secret room where, apparently, the suspect has set up an atelier where he can pursue his interest in painting. The room contains easels, canvasses, oil paints, etc. The police seize some of these materials as evidence. As they are leaving the house, they ask the wife about her husband’s art room. She is confused. She is unaware of the room’s existence and didn’t know that her husband had any interest in painting. Later, this will become a problem. Reviewing the situation, a public prosecutor tells Bobby Dees, “We may be okay on the search part, but as far as the seizure, the room was Hubby’s and Hubby’s alone. Debbie LaManna’s claiming she didn’t even know it existed. If this guy is our Picasso, the argument that LaManna’s slick defense attorney will eventually make is that the wife didn’t have the authority to the seizure of her husband’s things that she clearly had no control over. I don’t want to be argumentative or rain on your search warrant parade, but…” Frequent legal hairsplitting like that often makes the book feel like a legal thriller. Most accurately, however, I’d say that it falls into either the police procedural genre or the straight-out thriller category. Though the Cupid killings of Retribution are occasionally referenced by characters in Pretty Little Things, this book is not a sequel. On the other hand, Retribution, though it works as a standalone thriller, has, to date, received three direct sequels featuring C.J. Townsend as the protagonist. In at least two of these sequels, the Cupid killings continue to be a main element of the story. I have read only one of the sequels, Last Witness, published in 2005. Alas, of the three Hoffman novels I have read to date, this was the weakest by far.

Last Witness isn’t just the second book in the C.J. Townsend series of legal thrillers, it is very much a direct sequel to Retribution, and William Bantling and the Cupid killings both play major roles in the novel. If you scroll through the reader reviews of Hoffman’s thrillers on Goodreads.com or Amazon.com, you’ll find quite a few people complaining about Hoffman’s excessive use of acronyms and alphabet agencies. This wasn’t a big problem for me in Retribution or Pretty Little Things, but in Last Witness it is a fairly major annoyance. Some of this may be unavoidable. South Florida has a lot of different law enforcement agencies: Miami-Dade Police Department (MDPD), Miami Police Department (MPD), Miami Beach Police Department (MBPD), Broward’s Sheriff’s Office (BSO), FHP (Florida Highway Patrol), and so forth. But nearly every page of the book contains multiple law-enforcement abbreviations: FDLE (Florida Department of Law Enforcement, which I couldn’t help thinking of as “fiddle,” though no one in the book refers to it as such), MROC (the Miami Regional Operations Center of FDLE), SAO (State’s Attorney’s Office), ASA (Assistant State’s Attorney), DCJ (Dade County Jail), QSL (a police code for “I receive”), CJN (Criminal Justice Network), ECU (Economic Crimes Unit), DVU (Domestic Violence Unit), MCU (Major Crimes Unit), CCS (Criminal Conspiracy Section), SAC (Special Agent in Charge), CO (Correctional Officer), AUSA (Assistant United States Attorney) IA (Internal Affairs). These are in addition to the many fairly common abbreviations found in a lot of other crime fiction: FBI, BOLO, ME, DB, DEA, ATF, DUI, etc. And there are other non-law enforcement abbreviations – for instance SoBe for South Beach – that can be confusing if you are not a Floridian. Here’s a typical sentence from Last Witness:

“MDPD, MBPD, FDLE, FHP – and practically every other police department in Miami, including the twenty-four-man department of Surfside P.D. – assuaged the fears of the citizens in their jurisdictions with reports of the investigation and the precautions their officers were taking.”

Often these abbreviations are confusing, especially if you don’t remember what they stand for. I encountered several references to FSP and assumed it was a reference to the Florida State Police department. Later, it became clear that this was a reference to the Florida State Prison. I must have missed the first reference to this acronym, where it was probably explained.

Sometimes the confusion is sort of accidentally amusing. At one point, a character named Manny says, “Move over JFK, there’s a new conspiracy theory in town.” One page later, Manny says, “LBJ is still missing…” At first I thought this was some sort of humorous reference to Lyndon Baines Johnson, meant to connect with the JFK reference. But then I remembered that, nearly 200 pages earlier, Hoffman had introduced a minor character named “Jerome Sylvester Lightner aka Lil’ Baby J, aka LBJ.”

I frequently found the use of all these acronyms and abbreviations confusing (I’m still not sure what the acronym IMPACT stands for, though I know it’s some sort of law-enforcement agency), but I’m not sure what Hoffman could have done to fix the problem. South Florida has a bewildering array of law-enforcement agencies. I wouldn’t have wanted Hoffman to pretend that every cop in the book was a member of the Miami Police Department. The turf wars that take place between the various agencies is a major element of all of the Hoffman novels I have read so far. I think that she creates a real sense of authenticity by having her cops and lawyers employ numerous acronyms and abbreviations in their speech. But she definitely should have included, at the front of the book, a glossary of every single acronym and abbreviation used in the novel. And she also should have found a way to avoid them as often as possible. For instance, the above-quoted line doesn’t have to begin with, “MDPD, MBPD, FDLE, FHP – and practically every other police department in Miami, including the twenty-four-man department of Surfside P.D…” She could have just written, “Practically every police department in Miami…”

Despite all of these complaints, I actually enjoyed Last Witness. It’s a true sequel, so don’t even attempt to read it if you haven’t already read Retribution. It ends with a clear indication that the next book in the series will also deal with Bantling and the Cupid murders, so keep that in mind as well. I’m not sure I want to spend any more time with Bantling, so I may just skip the rest of the series. But I like Hoffman’s writing and plotting enough that I have ordered copies of two of her standalone novels, 2007’s Plea of Insanity and 2015’s All the Little Pieces.

One amusing thing about Hoffman’s C.J. Townsend novels is that she has made Townsend a native of my hometown, Sacramento, CA. When Townsend is experiencing horrific trauma in New York City or Miami Beach, she is often urged by her parents to return to placid Sacramento. At one point in Last Witness, C.J. flees Miami and holes up in a small apartment in Santa Monica, California, which is located in Los Angeles County. Of the choice of Santa Monica, Hoffmann writes, “It was not the soothing comfort and familiarity of Mom and Dad and old friends in quiet Sacramento that she sought – rather it was anonymity.” Hoffman appears to have never visited Sacramento and to have picked it at random as C.J.’s original hometown. Sacramento has been the scene of numerous sensational crimes. Patty Hearst was an accessory to the murder of an innocent bystander in a bank robbery here in 1975. Sacramento native and serial killer Richard Chase was known as the Vampire of Sacramento because he drank the blood of his victims. Dorothea Puente killed nine disabled renters at her Sacramento boarding house and buried them in her backyard. Manson family member Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme lived in Sacramento for a while and attempted to assassinate President Gerald Ford in Sacramento’s Capitol Park. The list goes on and on. Sacramento is not a sedate and quiet city – except, apparently, in the crime novels of Jilliane Hoffman. Not only do I forgive her for this fault, I think it’s kind of sweet.

For some reason, Hoffman seems to have a huge following in Germany. Many of the online reviews at Goodreads are written in German. But Hoffman isn’t a complete unknown in the land of her birth. On Goodreads, Retribution has more than ten thousand ratings, with an over all average of 4.09 out of five stars. On Amazon.com, many of her novels have attracted a few thousand reader reviews. But I still get the feeling that she should be better known. I think her thrillers are better than Turow’s and Grisham’s. I’d rank her alongside Tess Gerritsen as one of our best living thriller writers. But Gerritsen is far better known than Hoffman. At Amazon, Gerritsen’s thriller The Spy Coast has garnered more than eighty thousand reader reviews, although it was published less than two years ago. One thing that might be holding Hoffman back from pop-fiction superstardom is the fact that she has published only eight novels over the course of her twenty-year career. Grisham and Gerritsen reliably provide a new book every year or so. In any case, I plan to keep on seeking out more of her work. If you are a fan of pop-fiction thrillers, I recommend that you do so also.