WILLIAM SHATNER'S GUEST-STAR TREK

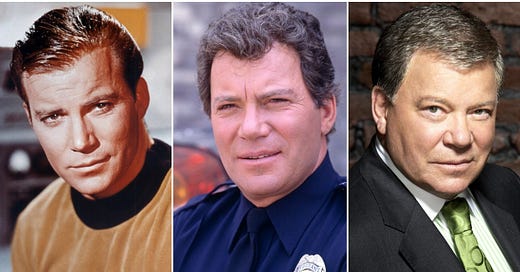

William Shatner, who turns 94 on March 22, will always be best remembered for embodying one of the most iconic characters in television history, Captain James T. Kirk on the original Star Trek series. The series, and Captain Kirk, were both created by Gene Roddenberry, and he deserves a lot of credit for the enduring power of both the program and the character. But it was Shatner who made the character indelible. By the 1990s, a lot of people had begun to think of Shatner as a sort of caricature of the shameless ham, the TV actor who overplays every role. And, indeed, he was so good at playing that role that he was hired to do just that as both a pitchman for the online travel agency Priceline and in TV shows such as The Practice and Boston Legal, in which, as the New York Times once noted, “He played the pompous, clueless, self-aggrandizing 70-something lawyer Denny Crane…William Shatner the man was playing William Shatner the character playing the character Denny Crane, who was playing the character William Shatner.”

If that sounds a bit confusing, it is probably because no actor has ever really had a career quite like Shatner’s. Scroll through his credits at the Internet Movie Database and you’ll discover that he has played “William Shatner” in a wide array of projects: an episode of The Big Bang Theory, the 2002 film Showtime (starring Robert De Niro and Eddie Murphy), an episode of Futurama, the 2009 film Fanboys, a Bruno Mars music video, Shatner’s own spoken-word video for It Hasn’t Happened Yet, an episode of The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, the 2012 film Horrorween (in which Donald Trump also appeared as himself), the TV series Hashtaggers, and so forth.

If you watch episodes of the original Star Trek nowadays, Shatner can seem to be overplaying his part. This is also true of many of his 1960s and 1970s guest-starring appearances. But Shatner wasn’t really hamming it up. He only appears to be doing so nowadays because our TVs have gotten so much bigger and their pictures have gotten so much clearer. In the 1960s, like most American families, my family owned a single TV set, which was capable of producing only black-and-white images and was miniscule by today’s standards (23 inches measured diagonally). The TV sat in our basement family room and got mediocre reception (this was long before satellite and cable television made TV images much sharper). If someone turned on an appliance in another room, it could cause the TV screen to grow fuzzy. If someone walked on the floor overhead, it could mess with the reception. Sometimes, in order to get a clear picture, you had to toy with the “rabbit ears” (a pair of antennae) on top of the TV. Many a 1960s TV set had tinfoil connecting the two ears of the antennae. Sometimes, just the way the electrical chord in the back of the TV was draped or coiled could alter the picture. If the wind outside blew strong enough to cause the big antenna on our roof to vibrate, the screen could grow fuzzy. TVs were so fussy back then, that in order to operate them you had to be handy with knobs that read “horizontal hold,” “vertical hold,” “contrast,” and so forth. It’s possible that my current, flat-screen plasma TV has control buttons like that, but I haven’t used any of them in the ten years that I’ve owned it. And rabbit ears appear to be a thing of the distant past (except on rabbits, of course).

In other words, TVs were small in the days when Shatner went to work in Hollywood, the images projected on screen were often fuzzy, the sound could be even fuzzier, and, to top it all off, most of in the baby boomer generation were raised to believe that it was dangerous to sit close to a television while watching it. Tech journalist Ian Bogost of The Atlantic recently wrote an essay called Your TV is Too Good for You, in which he noted that, “Years ago, sitting too close was the problem. If you’re old enough to remember watching cathode-ray-tube sets, you may have been enjoined to give them space: Move back from the TV! The reasons were many. Cold-War-addled viewers had developed the (somewhat justified) fear that televisions emitted radiation, for one. And the TV – still known as the ‘boob tube’ because it might turn its viewers into idiots – was considered a dangerous lure. Its resolution was another problem: if you got close enough to the tube, you could see the color image break down into the red, blue, and green phosphor dots that composed its picture. All of these factors helped affirm the TV’s appropriate positioning – best viewed at a middle distance – and thus its proper role within the home. A television was to be seen from across the room…The media theorist Marshall McLuhan famously described television as a ‘cool’ medium, one that provides somewhat meager sensory stimulation, as opposed to a ‘hot’ medium such as cinema, which intensely targets the eyes and ears.”

My parents kept the TV in the basement because it was the only space big enough for us to watch it from a distance. The first and second floors of the house were divided into a variety of small rooms. The basement was essentially one long empty space. My whole family tended to gather in the basement on Saturday nights to watch TV. My parents sat in chairs that were about ten feet from the TV. My siblings and I sprawled out on a sofa and some chairs behind them. My parents weren’t being greedy, hogging the best spots in the room. They were protecting the eyes of their children by keeping them a good fifteen feet from the screen. It was often difficult to follow everything happening on a program from that distance.

Shatner seemed to understand all this better than just about any other TV actor of his era. While a lot of TV actors were trying to mimic the mush-mouthed vocal delivery of big-time movie actors like Marlin Brando or James Dean, Shatner went in the opposite direction. He enunciated his words carefully, and broke his sentences into bite-sized pieces, making each clause a separate unit of delivery. He would speed up his cadence at times, and then bring it to a near halt. Shatner’s unique speaking style has been parodied countless times. Among living actors, probably only Christopher Walken’s line delivery has generated more parodies. One of the more memorable Shatner impersonations was delivered by actor Jesse Plemons on an episode of Black Mirror called USS Callister, which was both a loving homage to the original Star Trek as well as a spoof of its excesses.

Most viewers under the age of fifty probably have a difficult time appreciating what Shatner was doing back in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. They’ve never been forced to view any of his performances on a small, black-and-white, cathode-ray TV set. But I grew up watching cathode-ray TV sets, and I can assure younger readers that it was always a treat whenever I knew that Shatner was going to be appearing on one of my favorite programs. This was because I knew that, even sitting ten feet or more away from my small TV set, I’d get a performance from him that would make it seem as if he were down there in the basement family room with me. Critics also appreciated what Shatner was doing in those early years. In June of 1958, Shatner co-starred, with Rod Steiger, in an episode of CBS’s Playhouse 90 called A Town Has Turned to Dust, which was written by Rod Serling and directed by John Frankenheimer. Time magazine’s reviewer wrote: “The result was far better than anyone…had a right to expect. Director John Frankenheimer caught the drought-heightened tension of the desert town, William Shatner was terrifyingly convincing as the rabble-rousing shopkeeper bent on avenging his hurt pride, Steiger made the drunken sheriff both scruffy and appealing, as Serling intended. Seldom has the hate-twisted face of prejudice been more starkly depicted.” In the New York Times, reviewer Jack Gould noted that A Town Has Turned to Dust contained “two of the season’s superlative performances by Rod Steiger and William Shatner.” Those performances were all the more impressive for being broadcast live. In the early days of television, actors had but once chance to get a performance right, and Shatner excelled at it.

Shatner was born, in Montreal, in 1931. Television first became a widespread phenomenon in the late 1940s, just as Shatner was reaching adulthood. He was born at exactly the right time to become one of TV’s first truly new stars. Many of the stars of TV’s first decade or so were has-been movie actors such as William Boyd (Hopalong Cassidy), George Reeves (Adventures of Superman), Robert Young (Father Knows Best), and Lucille Ball (I Love Lucy). Others came to television from radio, and the transition was not always easy. Shatner had a small role in a 1951 Canadian film called The Butler’s Night Off. In 1958, he gave a well-received performance in director Richard Brooks’s The Brothers Karamozov, and in 1961 he appeared in Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremburg. But most of Shatner’s pre-Star Trek work was for television. He and Leonard Nimoy (who played Mr. Spock on Star Trek) actually appeared together in a 1964 episode of The Man From U.N.C.L.E. Back then, a lot of people were predicting that Shatner’s career would soon follow the trajectories of Steve McQueen’s and Paul Newman’s, which began in the theater, then moved on to television, and eventually carried them to movie stardom. But it never happened. That 2010 New York Times Magazine profile of him notes that, “The great movie roles weren’t coming his way, so in the ‘60s, waiting for stardom, he took parts in forgettable movies like The Outrage and Incubus; guest roles on TV dramas like Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Twilight Zone; parts on TV serials like Route 66 and Gunsmoke and Dr. Kildare. At 35, he was a working actor who showed up on time, knew his lines, worked cheap and always answered his phone. In 1966, he accepted a starring role in a sci-fi series called Star Trek, joining a no-name cast, some of whom later accused him of being pompous, self-aggrandizing, clueless and insufferably William Shatner, which became his greatest role once he finally accepted the fact of it.”

It’s easy to understand why many of Shatner’s Star Trek cast mates might have resented him. With the exception of Nimoy, none of the others gained the kind of iconic status that Shatner did as a result of his association with Star Trek. His performances were big and showy and often overshadowed the performances of those who worked with him. But Captain Kirk was the main character of Star Trek. The character was written to be big and showy. A more subtle performance might have gotten the program cancelled after one season. Kirk’s closest associate/friend is Spock, a half-human/half-Vulcan whose father’s alien race values logic above all else and suppresses all emotion. In order for Spock to appear truly alien, he needed to be paired with a human who embraced all of the emotions – anger, fear, joy, anguish, love – with reckless abandon. Spock and Kirk were one of the great odd couples of a 30-year period in which TV embraced many an odd couple (Lucy and Ricky, Felix and Oscar, Samantha and Darren Stevens of Bewitched, Major Nelson and Jeannie of I Dream of Jeannie, Ilya Kuryakin and Napoleon Solo of The Man From U.N.C.L.E., Gil Favor and Rowdy Yates on Rawhide, Laverne and Shirley, etc.). If Shatner had toned down Kirk, Nimoy’s Spock wouldn’t have been as intriguing nor as interesting as he became. Shatner chewed a lot of scenery on Star Trek but no one can argue that his approach failed. It succeeded spectacularly. Unfortunately, Hollywood didn’t really appreciate how successful it had been until the show was cancelled and went into syndication. At that point it became an entertainment juggernaut.

Science-fiction novelist Tony Daniel has written two novels set in the world of Roddenberry’s original series. Both Devil’s Bargain (2013) and Savage Trade (2015) feature Kirk, Spock, and other original crewmembers of the Starship Enterprise, which makes Daniel a bit of an authority on the original series and Shatner’s role in it. Recently I emailed him to ask if any Shatner performances particularly impressed him. He told me, “One that’s generally considered good is the Harlan Ellison-based episode ‘The City on the Edge of Forever,’ where he goes back in time and has to decide whether to let Joan Collins live or die. It was like a little Twilight Zone stuck into Star Trek.” Daniel also noted that Shatner “was good with interacting with comic villain types, like Harry Mudd (‘Mudd’s Women,’ and ‘I, Mudd,’ episodes). He never just played the straight man, but brought a hint of roguish understanding to the lovable villains Kirk dealt with. What I liked most were Kirk’s love affairs. Shatner always played them in believable fashion. My favorite of these is ‘Requiem for Methuselah,’ where he falls for the android Rayna Kapec. It’s like a little Bladerunner in 49 minutes.”

The original Star Trek embraced the sex binary of its era. Later iterations have strayed from that artistic choice. Daniel thinks this was a mistake. “One of the great strengths of the original series (which the later series utterly lost) was the depiction of sexuality. Characters were male and female. They were attracted to one another when appropriate, and showed it. It spoke to and formed many a boy’s archetypes of sexuality in the 1970s and 1980s, when we all saw it via watching afternoon reruns after school. While cartoonish and a bit sadomasochistic at the time, and very 1960s, it was far truer to our underlying forever-fixed human nature than the sexless 1990s shows. Shatner was particularly good at playing a guy with a healthy sex drive, that is, a normal adult male.”

It isn’t just a coincidence that names like Richard Matheson, Harlan Ellison, and Rod Serling come up frequently in discussions of Shatner’s career. Academics frequently celebrate the work of various American literary schools – the American ex-pats of the so-called Lost Generation, the writers of the Harlem Renaissance, the Beats – but few literary salons have influenced American popular culture as profoundly as the Southern California fantasists who were all brought together by Rod Serling for his Twilight Zone series and later worked on other fantasy and sci-fi shows, including Star Trek. The best known of these were Serling himself (who wrote 92 Twilight Zone episodes) and Ray Bradbury (who wrote only one but was a mentor to many of the other writers). Charles Beaumont (who wrote 22 episodes of The Twilight Zone), Richard Matheson (14), and George Clayton Johnson (5) all had strong connections to Shatner. Johnson wrote episode one of the original Star Trek, “The Man Trap.” Shatner starred in two of Matheson’s Twilight Zone episodes. He also starred in two live dramas written for television by Serling prior to the creation of the Twilight Zone. He starred in an episode of the HBO anthology series Ray Bradbury Theater. He also starred in the 1962 Roger Corman film The Intruder, which was scripted by Beaumont. Both Shatner and Bradbury were good friends of Charles Beaumont, who, like a character out of The Twilight Zone, died of old age (well, early-onset Alzheimer’s) in 1967 at the age of 38. In 2015, when Penguin Classics published Perchance to Dream, a collection of Beaumont short stories, they used an introduction by Bradbury and an afterword written by Shatner. Shatner notes that The Intruder was a pro-integration story that was shot in southern Missouri in the early 1960s, at a time when the local population (at least the white members of it) were mostly anti-integration. The cast and crew lived in constant fear of attack by the locals. The experience bonded Shatner and Beaumont and they remained friends after returning to L.A. Shatner notes, as have a few other knowledgeable commentators, that the founding members of the Southern California fantasists – Beaumont, Matheson, Bradbury, etc. – originally referred to themselves (for unknown reasons) as the Green Hand. The name never really caught on. But Shatner is probably the only actor who starred in productions written by nearly every member of the Green Hand. Although he himself has written or co-written more than two dozen books, his greatest contribution to pop-fiction is probably the work he did on programs like The Twilight Zone and Star Trek to help popularize writers such as Matheson, Beaumont, Johnson, and the others.

The Times profile of Shatner notes that, “After Star Trek was cancelled in 1969, he appeared in more schlock movies – Big Bad Mama, The Devil’s Rain – and as the lead in a TV series, Barbary Coast, that never caught on. So he guest-starred on game shows: The Hollywood Squares, Celebrity Bowling, not even a regular among C-listers.” This isn’t actually fair to Shatner and elides a great deal of his best acting work. Some of the programs he guest-starred on may have been mediocre – Medical Center, Ironside, Owen Marshall: Councilor at Law – but the performances rarely were. What’s more, Shatner also did guest work on some of the best-known shows of the era, such as Hawaii 5-O and Mission: Impossible, programs that are still part of viable franchises.

Recently, my wife and I binged some episodes of Barnaby Jones on Amazon Prime. Our TV screen is 35 inches (modest by today’s standards), our picture is generally razor sharp, and we sit only about eight feet from the TV. Barnaby Jones starred Buddy Ebsen as an elderly Los Angeles private detective, and ran on CBS-TV from 1973 to 1980. Shatner guest starred on the program’s second episode. Julie and I hadn’t watched an episode of Barnaby Jones since the 1970s. The pilot episode, which guest starred William Conrad and Bradford Dillman (among others) was entertaining enough. All of the performances seemed properly modulated to one another. But in that second episode, “To Catch a Dead Man,” most of the performances seemed to pale in comparison with Shatner’s. Unlike, say, Columbo or The Rockford Files, Barnaby Jones wasn’t prestige 1970s television. It was a slightly above average TV detective show. The plots were predictable and the characters were generally underwritten. Shatner’s character is a rich married man who fakes his own death in order to start over again under an assumed name with his mistress. We are told almost nothing of importance about Phillip Carlyle. Nonetheless, Shatner makes him memorable. It isn’t just his line delivery that stands out. His facial expressions, his body language – everything about the character is eye-catching. Shatner’s highly animated performance pairs particularly well with Ebsen’s trademark laconic style. Julie and I enjoyed it tremendously, but we also noted with regret that younger viewers, seeing it for the first time, would likely find Shatner’s performance to be campy. And, sadly, on a big-screen TV with a crisp picture and excellent sound, Shatner’s performance does come across as over the top. But Shatner didn’t modulate his performance to the standards of today’s high-def TVs. Even in 1973, about half of all American TV sets were still black-and-whites and the average screen size was 23 inches. On the pilot episode of Barnaby Jones, Bradford Dillman’s villain was largely unmemorable. And viewed by someone back in 1973, on a cathode-ray TV set sitting ten feet across the room, the villain would have been practically an afterthought. Nowadays, watching it on a 35-inch high-def TV, Dillman’s performance is just fine. His character (a Bobby Kennedy-wannabe) is as poorly written as Shatner’s was, but the actor’s boyish good looks and slight smarminess come across in a way that wouldn’t have been nearly as effective fifty years ago.

A lot of well-known actors appeared as guest stars on Barnaby Jones – Margot Kidder, Roddy McDowell, Don Johnson, Ed Harris – but none of them ever made a bigger impression than Shatner. Although best remembered for starring in Star Trek, he was one of the busiest TV guest stars of his era. His performance in “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” helped make it one of the most memorable episodes of The Twilight Zone ever (although Richard Matheson’s script deserves much of the credit). Shatner was also the star of a Twilight Zone episode called “Nick of Time,” also regarded as a classic. In Rod Serling: His Life, Work, and Imagination, author Nicholas Parisi writes, “’The Howling Man’ aired on November 6, 1960, The Following week, Serling’s ‘Eye of the Beholder’ debuted. And one week later came Matheson’s ‘Nick of Time.’ This three-week period likely constituted the pinnacle of the series.”

Shatner’s performance in a season-five Columbo episode called Fade In to Murder is a great piece of meta-fiction. He plays an actor named Ward Fowler who has become famous as the star of a fictional TV series called Detective Lucerne. He is now such a big star that he can make all kinds of ridiculous demands of the studio and the program’s producers. This was an inside joke. Peter Falk was in the final year of a five-year contract as Columbo, and was eager to leave the series and make movies. At least that was his claim. He used the program’s enormous popularity to negotiate a huge raise in pay and then continued to play Columbo for two more seasons (later the program would be resurrected by a different network and Falk would return for more episodes, but many fans consider only the episodes made between 1968 and 1978 to be canonical). In his book The Columbo Phile, author Mark Davidziak notes, “Shatner’s portrayal helps a good deal here. The glimpses of his Detective Lucerne remind us of how phony most television detectives are. His Ward Fowler, though, is a character with several intriguing shadings.” In his book Shooting Columbo, author David Koenig writes that Ward Fowler is “played to the hilt by William Shatner.” And in The Columbo Companion, a blogger known as The Columbophile, writes: “Shatner and Falk really seem to hit it off. Both are blessed with an inherent likeability which they put to excellent use in several scenes. Perhaps the best example is when Fowler finds Columbo in his trailer trying on his trademark hat and shoes. Their interchange feels charming and authentic…the chemistry between leads is unmistakable.”

Shatner would return to Columbo eighteen years later, in 1994, in an episode called Butterfly in Shades of Gray, in which he played Fielding Chase, a bombastic rightwing radio host. The producers wanted him to pattern his character after Rush Limbaugh. They wanted Chase to be an enormous blowhard. But by now TV screens were bigger and picture quality was much better and Shatner must have instinctively understood that, if he played the character as broadly as the producers wanted him to, the performance would come across as camp. Instead, according to David Koenig, “He tried to channel Firing Line’s William F. Buckley, Jr… ‘I tried to do his voice and his arrogance of personality,’ Shatner revealed.” Shatner’s choice was the right one. The character is bold and brash but he also comes across as intelligent and believable, something that a Limbaugh lampoon probably couldn’t have achieved.

Much of Shatner’s best guest-star work was done during his wilderness years, between the cancellation of the original Star Trek in 1969 and its triumphant revival on the big screen ten years later in Star Trek: The Motion Picture, directed by Robert Wise, one of Hollywood’s most bankable filmmakers (The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Sound of Music, West Side Story, etc.). Despite a lukewarm critical reception, the film set a record for opening-weekend receipts at the box office and was the fifth highest grossing movie of 1979, although its huge budget ($44 million) made it less profitable than many of the year’s other big hits, such as Kramer vs. Kramer (made for $8 million) and The Amityville Horror ($4.7 million). Nonetheless, the film revived both the franchise and Shatner’s star power. It was followed by five sequels, released between 1982 and 1991, the first of which, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, also set a record for opening-weekend receipts and is still widely regarded as the best Star Trek film of all time. Shatner wasn’t the type to sit around and relax between film roles, so he also took on the starring role in a TV action drama called T.J. Hooker, which debuted in March of 1982, less than three months before the release of Star Trek II. He played the title character, a former police detective in a fictional California city (clearly meant to be Los Angeles) who goes back to being a patrol officer after his partner is killed. Hooker has plenty of Captain Kirk in him, but he is older than Kirk, divorced, despondent over the loss of his former partner, and thus Shatner often (but not always) tones down the theatrics for which he was famous, turning Hooker into a sadder but wiser version of Kirk. What’s more, Kirk was clearly intended to be the sexiest character on Star Trek, but on Hooker, Shatner is supported by much younger and more attractive actors, particularly Adrian Zmed, as Hooker’s new patrol partner, and Heather Locklear, as a rookie cop whom Hooker helps train and mentor. Prior to landing a role on T.J. Hooker, Zmed had plenty of theatrical experience, having appeared in Grease and other stage musicals, but in 2016, he told an interviewer for Las Vegas Magazine that it was Shatner who taught him how to act for the TV cameras: “I learned so much just watching him...it's a very different energy on camera than onstage. Instead of reaching the last person 50 rows away from you, you're reaching someone three feet in front of you, which is really daunting...His camera technique was just incredible. He was so relaxed and all. I learned so much in terms of the moment, on how you readjust your energy, how you get efficient with camera technique. And just the stories. When he directed, he would mentor me. I do consider Bill a mentor, no question about it.”

As Zmed’s comments show, by the 1980s, Shatner had changed his approach to television acting somewhat. Now he was modulating his performances for viewers who were sitting just a few feet away from the screen. And the screens of the 1980s were generally larger and projected a crisper picture than the screens of earlier decades. T.J. Hooker isn’t remembered as a landmark television program but it was actually more commercially successful than the original Star Trek. Hooker ran for five seasons and generated 91 episodes. Star Trek ran for three seasons and 79 episodes. Ironically, neither of these programs provided Shatner with his longest-running TV stint. Between 1989 and 1996 Shatner narrated 186 episodes (plus two specials) of a nonfiction program called Rescue 911, which recreated real-life incidents that led to calls to 911 emergency dispatch centers around the country. It was the opposite of prestige TV, a low-budget program that appealed mainly to indiscriminate TV viewers, but Shatner committed to it as enthusiastically as he did to all of his projects. As noted by the New York Times, he had a working-class sensibility and hated to turn down any paying work. Later he would appear in five seasons (101 episodes) of Boston Legal, which was created by David Kelley as a spinoff of his successful legal drama The Practice. British barrister and writer John Mortimer was brought in as a consultant on Boston Legal, and he seems to have injected Denny Crane (Shatner’s character) with some of the characteristics of his famous fictional barrister Horace Rumpole. Both are older men who think highly of their legal skills, are largely dismissive of their colleagues, and prefer performing in front of a jury to the actual nuts and bolts of case law and judicial procedure.

Had Shatner been born in 1962 rather than in 1932, he would have been reaching his prime just as the so-called “second golden age of television” was arriving, which most authorities date to the debut of The Sopranos in 1999. And, almost certainly, his approach to television would have been much different than it was back in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, when the technology was so much different than it is now. He might have taken his place among actors like James Gandolfini (born in ’61), Bryan Cranston (’56), Bob Odenkirk (’62), and Jon Hamm (’71), all of whom embodied iconic characters of the era. Instead, Shatner is often written off as a second-rater. Ironically, however, he himself, albeit indirectly, probably helped usher in the era of prestige television. Not all TV authorities believe that prestige TV began with The Sopranos. As Wikipedia notes: “Stephanie Zacharek of The Village Voice has argued that the current golden age began earlier with over-the-air broadcast shows like Babylon 5, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (both of which premiered in 1993), and Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997).” Both Babylon 5 and Deep Space Nine are heavily indebted to the original Star Trek. J. Michael Straczynski, who created Babylon 5, was trying to create an “anti-Star Trek,” a show similar to Roddenberry’s original but with science that actually worked and interplanetary politics that were more complicated and believable. He even occasionally employed some big names from Star Trek – writer D.C. Fontana and actor Walter Koenig, for instance – to channel some of its energy. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, as the name makes clear, is an actual spinoff of Roddenberry’s original (although some have accused it of being a rip-off of Babylon 5). Even Buffy, with all of its alien creatures and over-the-top villains, seems to owe something to Star Trek. Shatner may not have been a big part of the second golden age of television, but Star Trek itself seems to have been.

Most fans probably prefer the work Shatner did as a regular player on various TV and film franchises to his other work. But it would be a mistake to write off his wilderness years, as the New York Times did, as nothing but a series of schlocky jobs done for nothing more than a paycheck. Shatner guest starred in some of the best TV shows of the 1970s and some of the silliest. But whether he was playing a role in Police Story or The Six Million Dollar Man or Mannix or Hawaii 5-O or Mission: Impossible or Kung Fu he was usually the best thing in it. In Billy Wilder’s classic 1950 film Sunset Boulevard, Gloria Swanson plays Norma Desmond, a silent film star whose career is in decline. When William Holden’s character tells her, “You used to be in silent pictures. You used to be big!” Desmond responds, “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.” Something similar has happened to Shatner’s great TV performances of the mid twentieth century. Nowadays they seem overly large and elaborate. But it isn’t the performances that have gotten too big, it’s the television sets. Alas, the only people who are likely to appreciate that fact these days are aging baby boomers like myself, who grew up watching him on tiny TV sets, with snowy picture screens that sat ten feet away from us. He brought us high-def, wide-screen, full-color performances despite the fact that he was working in an era of small, balky, black-and-white TV sets. And that probably explains why he has lived long and prospered.