WHO WAS THE FIRST BABY-BOOMER DETECTIVE IN AMERICAN FICTION?

The baby boomers are usually defined as Americans born between 1946 and 1964. Millions of American men had been mustered out of the armed forces by 1946 and had come home to resume their civilian lives. And one of the things they did in large numbers was sire children. The baby boom produced a great crop of mystery and crime novelists, including such luminaries as Michael Connelly (born 1956), James Ellroy (1948), Patricia Cornwell (1956), John Grisham (1955), Harlan Coben (1962), and Diane Mott Davidson (1949).

I visited the Wikipedia page for the year 1946 and scrolled through the list of prominent births for that year. Surprisingly, I found no famous Americans known primarily for writing crime and mystery fiction. The first famous American born in 1946 who would write a mystery novel was Dolly Parton. But Parton’s debut crime novel wasn’t published until 2022, and it was co-written by James Patterson. She is best known as a great American singer-songwriter. On Christmas Day, 1946, another famous American singer-songwriter was born, Jimmy Buffett. In 1992, Buffett published a novel, Where is Joe Merchant?, that can legitimately be described as a mystery. But no one thinks of Jimmy Buffett as a crime writer. Curiously, the first American baby boomer I could find who has made a significant contribution to American crime and mystery fiction was Stephen King, born September 21, 1947. King’s first published story, The Glass Floor, a mystery tale, was published in the autumn 1967 edition of Startling Mystery Stories. Thus, Stephen King may well have been the first baby boomer to publish a work of crime fiction.

But who was the first fictional baby boomer detective? That’s a more difficult question to answer. You could make a case for Nancy Drew. Although the character first appeared in 1930, she never grew much past the age of 16. What’s more, the series was given a makeover in 1959, to make the character more relevant to the baby boomers who were now her primary readers. But this seems a bit of a cheat. If we allow Nancy Drew to enter the competition, she would become the first fictional sleuth for every single American generation since the 1930s, because she’s been in print for nearly a hundred years and has remained a teenager throughout all that time. Also, the 1959 makeover actually made Nancy Drew somewhat less like the typical boomer girl. For example, the makeover made her less of a tomboy, more deferential to men, and more religious than she had been in previous incarnations. Boomer women tended to be less deferential to men and less religious than the women of their parents’ and grandparents’ generations. Nancy Drew may have been a 16-year-old detective in 1959, but she read more like a member of the GI Generation or the Silent Generation than a member of the Boomer Generation. The same thing is true of the Hardy Boys, who made their debut in 1927 but were substantially revised in the late 1950s to make them more relevant to baby boomer readers. If we allow them into the competition, they will simply create all sorts of arguments about whether they were true baby boomers or not.

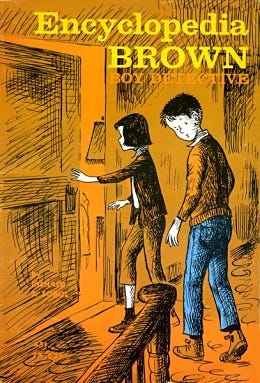

Since I’m interested more in hardboiled crime fighters rather than underage sleuths, I should probably eliminate all young adult crime novels from consideration. But, in the interest of fairness, I should point out that Donald J. Sobol’s Encyclopedia Brown character, who first appeared in 1963, was ten years old when he made his debut, and thus a baby boomer. Technically, he may be the first fictional baby boomer detective in American literature. Alas, the books he appears in are not really novels. They tend to be collections of very short vignettes, in which Leroy “Encyclopedia” Brown solves a mystery while sitting at the dining-room table and listening to his father, a police chief, explain some vexing mystery to him. Encyclopedia Brown rarely does any of the things that fictional detectives are known for. He doesn’t usually confront criminals or engage in fisticuffs or gunplay. He doesn’t conduct stakeouts or bring perps in for questioning. His life is never threatened. He’s just a preternaturally bright kid with incredible powers of observation.

A strong contender for the title of first baby boomer detective in American fiction is Gregory McDonald’s Irwin Maurice Fletcher, better known simply as Fletch, the protagonist of nine crime novels. The first novel in the series, also simply called Fletch, was published in 1974 but didn’t become a commercial phenomenon until the paperback appeared the following year. In that first book, Fletch claims to be 29 years old, which would mean that he was born in 1945 and, therefore, was not technically a boomer. But throughout the novel other characters react with surprise when they hear his age. They seem to think he is much younger. It is entirely possible that he is only about 25 and is lying about his age in order to be taken more seriously as an investigative journalist. If so, that would mean that he was born around 1949, making him a true baby boomer. His creator, Gregory McDonald, was born in 1937, and was not a boomer himself. But he nonetheless grew up primarily in post-war America, was raised like the boomers on TV, rock-and-roll, and American exceptionalism. You could argue that Fletch, who is employed as an investigative reporter, is not a true detective. But if we exclude from the rolls of fictional detectives any character who lacked an official title of detective or inspector then we would lose quite a lot of great detectives, including Miss Jane Marple, Jessica Fletcher, Father Brown, Cadfael, Ellery Queen, Richard Castle, Nancy Drew, the Hardy Boys, and plenty of others.

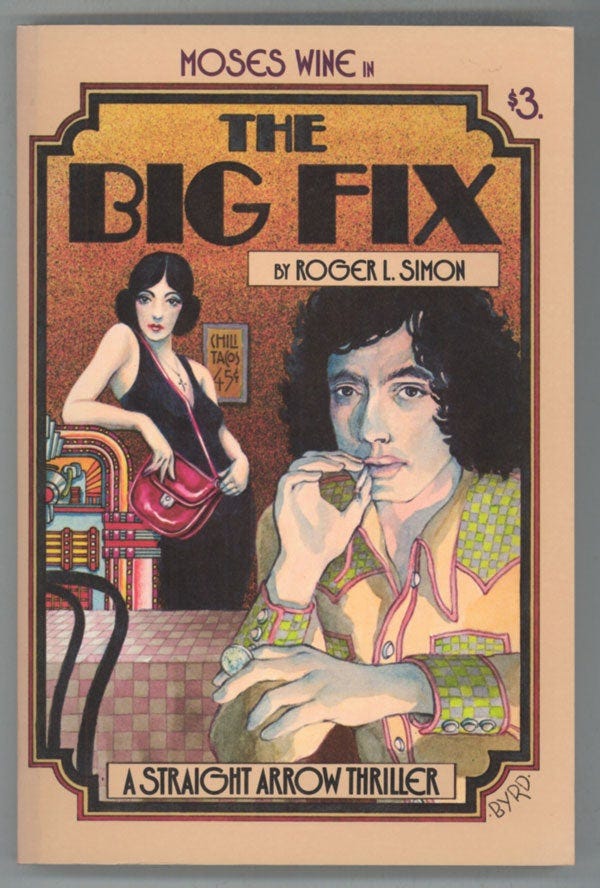

Another contender for the title of first baby boomer detective is Moses Wine, a character who first appeared in Roger L. Simon’s novel The Big Fix, published one year before Fletch, in 1973. In 1972, Simon approached Alan Rinzler, an editor at Straight Arrow Books of San Francisco, with a novel he had written. Rinzler didn’t think it could find a market. Straight Arrow Books was owned by the people who published Rolling Stone magazine, so Rinzler suggested that Simon try writing a novel that would appeal to Rolling Stone’s readers – young people who were into pot, rock-n-roll, anti-war protests, etc. Simon was living in L.A. at the time and reading a lot of Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald. He decided to create a private investigator who was young and edgy and long-haired. The result, produced in just six weeks, was The Big Fix, published by Straight Arrow in 1973. Here is the opening paragraph:

The last time I was with Lila Shea we were making love in the back of a 1952 Chrysler hearse parked across the street from the Oakland Induction Center. Teargas was seeping through the floorboards and the crack of police truncheons was in our ears. I could barely hear her little cries over the wail of sirens. That was the fall of ’67 – The October Days of Protest – and just a few minutes after we finished, she bounced off my chest over the Army surplus air mattress, pulled up her cotton panties and disappeared into the night without so much as a see-you-later.

Simon was six years younger than McDonald and his boomer protagonist seems, at first glance, like more of the real thing than Fletch. So why do I have trouble giving Moses Wine the title of first baby boomer detective? The Big Fix and its first few sequels are very good. But Moses Wine was clearly created as an amalgamation of a bunch of traits popular in media presentations of baby boomers at the time. These traits – campus radical, anti-war, drug-user, etc. – didn’t really define very many boomers of the era (baby boomers, for instance, supported the Vietnam War in greater numbers than their parents did). If you were to create a Millennial private eye and make him addicted to avocado toast and Tik Tok, and then have him living in his mother’s basement, you’d create a stereotype that probably fits very few actual people. Moses Wine is a fun spoof of baby boomer clichés but Fletch feels more real. Like most boomers, he didn’t dodge the draft (in fact, he earned a Bronze Star for his service in the Vietnam War). He’s not obsessed with rock-n-roll, and he’s more of a drinker than a recreational drug user. What’s more, Fletch appears to have been born after 1946, the official start of the baby boom. The first edition of The Big Fix reproduces a copy of Moses Wine’s application for a private investigator’s license. It shows that Wine was born on November 4, 1941. That’s almost exactly one year before the birth of Joe Biden, our current president and no one’s idea of a baby boomer. The baby boom was a postwar phenomenon and Wine was born pre-war (i.e., before America entered the war). Of course, back in the 70s, the term “baby boomer” simply meant anyone not old enough to remember the Second World War very well, someone whose childhood included lots of television, and who preferred the music of Elvis Presley to Frank Sinatra. So if you want to argue that Moses Wine was the first baby boomer to headline a series of American crime novels, knock yourself out. But technically speaking, he doesn’t qualify.

You could also argue that the three members of TV’s The Mod Squad, which ran on ABC-TV from 1968 to 1973, were the first fictional detectives of the baby boom era. That would make the numerous Mod Squad TV tie-in books of the late 60s and early 70s the first series of American crime novels featuring boomer detectives. If you are a literary snob, you may think that TV tie-in books are beneath your consideration. But if you are a literary snob, you probably think all genre fiction is beneath your consideration. I happen to be a fan of TV tie-in novels, and many of the Mod Squad tie-in books were written by Richard Deming (1915-1983), who was one of the most prolific crime writers of his era. He also wrote a number of Ellery Queen stories and was a prolific contributor to Alfred Hitchcocks Mystery Magazine.

But were the members of the Mod Squad true boomers? Not exactly. Of the program’s three stars, only Peggy Lipton, born August 30, 1946, was a genuine boomer. The other two were born in 1939 (Clarence Williams III) and 1940 (Michael Cole). By that reckoning, pretty young flower child Julie Barnes, a runaway from San Francisco and the daughter of a prostitute, described in the program’s promotional literature as a “canary with a broken wing,” was the first boomer crime fighter both on TV and in American pop fiction. And Richard Deming was the first person to include her in a novel, The Greek God Affair, published in 1968. Julie is the first character we meet in that book. Here are the opening sentences:

Three young people sat on a bench in the waiting room of Juvenile Division, surreptitiously examining each other. The girl, a slim ash blonde with brown eyes, delicate features and an exceptional figure, looked about eighteen.

She is the first of the three to be interviewed by LAPD Captain Adam Greer, who is looking to recruit some young people for a task force he is assembling to fight crimes by and/or against juveniles, a “mod squad,” as it were. He has deliberately sought out young adults who have juvenile arrest records. He figures this will give his mod squad street cred, help them blend in when they go undercover.

Julie is at first resistant to the idea of joining the LAPD. “Me a cop? Why, less than a year ago I spit right in a cop’s face!” She also points out that she is not of age. Captain Greer notes that she will be of age by the time she graduates from the LAPD training academy. The book doesn’t say so, but the minimum age for an LAPD officer has always been twenty-one. Thus Julie must have been twenty when she was offered a spot on the mod squad. Of course, The Mod Squad, is a work of fiction. I suppose it is possible that Captain Greer got permission to recruit people as young as eighteen for his special unit. But whether Julie is eighteen, twenty, or twenty-one in 1968, she is still very much a baby boomer. And, despite the age of the actors who played them, the other two members of The Mod Squad, Lincoln Hayes (Williams III) and Pete Cochrane (Cole) are clearly meant to be baby boomers as well. They are described as being “perhaps a year older” than Julie. But since Julie was the first to interview with Captain Greer, you could argue that she was the first member of the mod squad. And, considering how many other firsts of the era were awarded to men, I think I’ll vote for Julie Barnes, the canary from Haight-Ashbury, as the first baby boomer detective in American fiction, even if that ruffles a few feathers. Sorry, Fletch.