WHEN POP CULTURE TRIED TO FIGHT GUN VIOLENCE

It is often said that politics is downstream from culture. In the 1990s, various films (Philadelphia, Love! Valour! Compassion!, etc), and TV shows (Ellen, Will & Grace) portrayed homosexuals in a sympathetic and unthreatening way. In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court decided, in a case called Obergefell v. Hodges, that the Constitution guarantees the right of gay and lesbian same-sex couples to marry. No one would argue that any particular cultural product, by itself, helped bring legal same-sex marriage to all fifty American states. But it seems likely that there is some connection between the enormous popularity of, say, Will & Grace, which concluded its original run in 2006, and the country’s wider acceptance of gay and lesbian relationships. When he was Vice President, Joe Biden noted, with characteristic overstatement, that the program “probably did more to educate the American public” about the lives of gay and lesbian people “than almost anything anybody has ever done so far.” And, according to Wikipedia: “In 2014, the Smithsonian Institution added an LGBT history collection to their museum which included items from Will & Grace. Curator Dwight Blocker Bowers stated that the sitcom used ‘comedy to familiarize a mainstream audience with gay culture’ in a way that was ‘daring and broke ground’ in American media.”

This raises the question of whether a blitz of anti-gun-violence cultural products – films, TV programs, songs, novels, etc. – might be able to push America towards a solution to its horrific levels of school shootings and other mass killings. You could argue, of course, that the culture is already awash in intellectual properties that denounce gun violence. Nearly every crime drama on TV and in the cineplex depicts its gun-toting villains as despicable subhumans richly deserving of the comeuppance they receive in the final act. But, of course, that comeuppance usually is dispensed by gun-toting good guys. And the whole purpose of most of these films is to allow the audience to revel in the gun violence that the film purports to denounce. In the 1992 film Unforgiven, Clint Eastwood (who also directed) plays Will Munny, a once-notorious outlaw who has sworn off gun violence and taken up farming. The film clearly depicts Will’s journey, from gunman to husbandman, as an honorable one. But, flat broke, Will eventually takes up his guns again (in a good cause, naturally) and eventually the film doles out a heaping helping of the gun violence it preaches against. The 2014 film John Wick (directed by Chad Stahelski) recycles pretty much the same idea. In it, Keanu Reeves plays a former assassin who comes out of retirement and butchers seemingly hundreds of men, in order to avenge the death of…his puppy. Clearly, these are not cultural products designed to turn people away from guns. Rather than deglamorizing weaponry, they make it seem cool and exciting.

Believe it or not, there was a time when American pop culture actually did put forth some genuinely sincere anti-gun propaganda films and books and songs and so forth. This trend began after the high-profile gun deaths of President John F. Kennedy, in 1963, and Malcolm X, in 1965. But it went into overdrive following the gun deaths of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy during the Spring and Summer of 1968. It’s not much remembered now, but those deaths proved debilitating for many of those who had shared the dreams of the two murdered men. As a teenager in the 1970s, I remember reading numerous profiles of politically active celebrities whose lives were forever altered by the deaths of MLK and RFK. Singer Rosemary Clooney was with RFK on the night he was murdered at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. As a result, she suffered a nervous breakdown and spent eight years in psychiatric therapy. Her career never fully recovered. Singer Bobby Darin was also there. He went into seclusion for a year following the murder. Journalist Pete Hamill was there, too. In 2008, he told an interviewer for NPR that RFK was the only politician he’d ever allowed himself to become good friends with. And after the politician’s murder, Hamill noted, a lot of politically engaged Americans went into a deep funk. They no longer wanted to become emotionally attached to charismatic leaders like King and the two Kennedys. “Forgive me, but that was the feeling. And I think a lot of people had it. A lot of people I knew stopped investing any kind of hope in politics.” Robert Vaughn, star of The Man From U.N.C.L.E., came from a long line of liberal Democrats. Even after becoming a TV star he pursued a Ph.D. in Communications from the University of Southern California. He wrote a dissertation about the McCarthy Era called Only Victims: A Study of Show Business Blacklisting. He had hoped to use his skills at communication to fight for political causes he believed in. According to Wikipedia, he was “the first popular American actor to take a public stand against the Vietnam War.” But he later told an interviewer that, after the assassination of Robert Kennedy, “I lost heart for the battle.”

But not every cultural heavyweight was broken by the deaths of MLK and RFK. Some of them became radicalized by those murders, channeling their sorrow and anger into their work. John Ball rose to literary prominence when his 1965 novel, In The Heat of the Night, earned an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America for best first novel. Two years later it was adapted into a film that was awarded a Best Picture Oscar at the 40th Academy Awards. In The Heat of the Night was Ball’s anguished denunciation of American racism. In 1969, a year after the assassinations of MLK and RFK, Ball produced a follow-up novel called Johnny Get Your Gun. It was an anguished denunciation of gun violence in America. It depicts the nightmare that follows when a nine-year-old boy in Pasadena, California, finds himself full of rage and fear and in possession of a .38 caliber Colt revolver. Here, Ball describes the thoughts of Pasadena homicide inspector Virgil Tibbs after learning that little Johnny McGuire has been involved in a shooting:

Guns, dammit, guns! The right to keep and bear arms was given when a raw young country was part of a great, wild, largely unknown continent. In crowded modern cities, a loaded gun was as lethal as a pit viper, a machine for killing and nothing else. Killing. First there was Kennedy and the bitter, terrible reality of a presidential assassination. Then Martin Luther King. As a Negro Tibbs could never forget that one. Because King had been more than just a prominent public figure who had been cut down; he had been the whole pride and hope of a long-suffering people, a man whose voice was listened to everywhere – and respected. The manhunt for his killer had been one of the most intensive in all history, but that did not bring King back, or his words, or give back to the Negro people their Nobel Prize winning peacemaker.

Then Robert Kennedy – three bullets from a small .22 had stopped his energy, his intensive drive, erased his victory over Eugene McCarthy, terminated in mid-flight his bid for the Presidency. One man, any man, could do it at any time.

It bit deeply into Tibbs’s being because so many who had fallen had been Negroes, leaders who had offended the Southern white establishment. And among the dead lay the white mailman who had gone to the South to ask for fairness for his fellowmen and who had left his life there. Because someone had a gun, a gun he could buy as easily as a stick of gum.

Ball’s novel was clearly written when the assassinations of King and RFK were still top stories in the news. It is filled with anti-gun sentiments that reflected the anger and frustration of many Americans at the time, especially progressives who favored the kinds of policies that King and RFK championed.

Like John Ball, Laura Z. Hobson was a Caucasian pop-fiction writer who made her name with a bestselling novel (1947’s Gentleman’s Agreement) that denounced racism in post-World War II America and was adapted into a film that won an Academy Award for Best Picture. And, like Ball, Hobson appears to have been radicalized against gun violence in America by the assassinations of MLK and RFK. Published in 1970, her novel The Tenth Month tells the story of Theodora Grey, a successful New York journalist, who becomes pregnant “out of wedlock,” as they said back then. The story is set in 1968, so abortion isn’t a legal option for Theodora. The assassinations of that year figure prominently in the story. While walking the streets of New York and trying to decide whether to keep her child or give it up for adoption, Theodora hears the news of MLK’s assassination coming from a storefront on Broadway. Here is her reaction, which probably mirrors the way Hobson felt when she heard:

Oh God No. She heard her own cry, wrenched from her, torn out of her throat, and suddenly the circumambient din of voices that had been overlapping in the evening air turned into an unbearable repetition: Martin Luther King, Martin Luther King, Martin Luther King was shot and killed, Martin Luther King, Martin Luther King –

She began to run in a dark invisible need to get behind walls, to close out the voices. Running reminded her that she must not run, and she changed to a rushing, gasping, walking. She was filled with fear, with pain, with hatred for the killer, for all killers, for all haters except the haters of haters; they were different, they were the good, the decent, the reasonable and loving, the ones who were flooded with fury at hate and death and killing.

When Theodora finally arrives home and turns on the television, Hobson tells us:

In the seconds that had to elapse before sound and image could appear she sank into the armchair as if she had been wounded, and when the first words came they were spurts of words clustered around the same shaken excitement she had heard on the street. “The assassin’s bullet”…”ambulance rushed to the hospital”…”possible conspiracy.” She was hurled back to that November day not five years before when other shaken voices were telling of bullets and blood splashing and assassination and conspiracy, and the two became one and she could scarcely see the small lighted screen through the scald of her sudden tears.

In later years, plenty of other novelists – from Stephen King to Don DeLillo – would write with greater distance and more authorial control about the horrific assassinations of the 1960s. Many of those later novelists would be better wordsmiths than Ball and Hobson. But Johnny Get Your Gun and The Tenth Month are nonetheless valuable cultural properties because they were written in the immediate aftermath of the 1968 assassinations, and what they lack in authorial control or cool-headedness, they make up for with the way that they capture exactly the kinds of thoughts that were running through the heads of America’s well-educated progressives. The nearly incoherent rage that rises up from these pages is probably as close as a contemporary fiction reader can get to understanding what those assassinations felt like in real time, to real people. Later in The Tenth Month, after Theodora hears about the assassination of RFK, Hobson writes:

It was like a maniacal replay of nightmare, a confusion and yet a sameness…Not again, not this time; there were limits to what you could stand.

But they stood it, his mother, his wife, his children, Mrs. King, her children, the people getting the official telegrams from Vietnam, the wives, the mothers, the children –

Hobson was putting into words what a lot of mothers and sisters and daughters and girlfriends were thinking at the time about all the violence committed by – and generally claiming the lives of – American men. For her trouble, she received reviews from the largely masculine critical community that portrayed her as just another hysterical female. A brief (and largely incoherent) review of The Tenth Month that appeared in Kirkus Reviews, began: “A gynecological soap opera – you might say a lady’s agreement – between Theodora Gray, a divorcee of forty, and her doctor when Laura, at the end of one affair and just starting another one, finds herself pregnant.” Even in a review of only 143 words in length, the anonymous critic managed to confuse the name of the author and her protagonist.

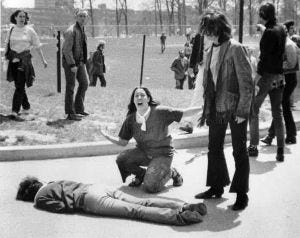

Some of the most powerful cultural responses to the gun violence of the 1960s and 1970s were rushed out in the heat of anger and inspiration. “Ohio,” a song written by Neil Young about the gunning down, by National Guardsmen, of four students at Kent State University during a protest of the Vietnam War, was recorded by Crosby Stills Nash and Young on May 21, 1970, just seventeen days after the incident occurred. It hit the airwaves in June of that year, when the tragedy was still highly topical, an impressive feat in an era of relatively unsophisticated musical recording and distribution facilities. (The song mentions only the “four dead in Ohio,” but an additional nine people were shot and injured during the debacle.)

A similar feat occurred in 1968, with the song “Abraham, Martin, and John,” which was written in the aftermath of the assassinations of MLK and RFK, managed to reach the airwaves by August of that year. Written by Dick Holler and recorded by Dion, it sold more than a million copies before the end of the year and became a hit not only in America but in Canada, New Zealand, Australia, the U.K., and elsewhere.

On May 8, 1970, four days after the shootings at Kent State, a mob of New York City construction workers who were opposed to the anti-War movement took to the streets in an incident that has come to be known as The Hardhat Riot.

Prior to the riot, film director John G. Avildsen (who would later make such hits as Rocky and The Karate Kid) had shot a film called The Gap (a reference to the so-called Generation Gap between hippies and their parents) about the friction between a New York City advertising executive named Bill Compton (Dennis Patrick) and his hippie daughter Melissa (Susan Sarandon, in her first film role). In a bar one day, Compton hears a factory worker named Joe Curran (Peter Boyle) ranting about how much he hates hippies and peaceniks. Eventually Bill and Joe travel to an upstate New York commune and together they gun down a bunch of hippies (including, unknowingly, Melissa). After the Hardhat Riot, according to David Paul Kuhn’s book Hardhat Riot, the movie was retitled Joe and “reedited to stress backlash [against the anti-war movement]. It was also rushed to release.” The website rogerebert.com backs this up: “Joe was originally to be titled The Gap, and it was supposed to focus on the chasm between businessman Bill Compton and his druggie daughter, Melissa. Then headlines and a stroke of casting genius set a different course.” [Sarandon claims that the film was altered simply because of Boyle’s brilliant performance: “They saw that they had a godsend in Peter Boyle and they re-edited it to emphasize him.”] In any case, the film was meant to be a denunciation of reactionary violence against the hippies of the anti-war movement. But in July 1970, shortly after the film’s release, Peter Boyle dropped into a theater and discovered that the audience was cheering the violence against the hippies. He thought he had been making a film that would denounce gun violence and instead the film had served, for some viewers, at least, as rallying cry to kill hippies.

None of the other artists mentioned in this article – John Ball, Laura Z. Hobson, Neil Young, etc. – suffered professionally for denouncing gun violence. Peter Boyle was one of the rare activist-artists who actually paid a price for his aversion to guns. So disgusted was he by the audience response to Joe, that he swore he wouldn’t participate in any film that could possibly be seen as a celebration of gun violence. After the success of Joe (it made $26 million on a budget of $106,000), he was offered the lead in a violent thriller called The French Connection. Boyle turned it down. Instead the role of New York Police Detective Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle went to Gene Hackman, who won an Academy Award for his performance. Though he worked in film and TV until his death, mostly in supporting roles, Boyle’s career never really recovered from that decision. Eventually, he abandoned his commitment to making only non-violent movies. He had to. Hollywood makes so few of them. When Boyle died in 2006, most of the obituaries emphasized his supporting role on the long-running sitcom Everybody Loves Raymond, on which he played the protagonist’s cranky father. Hackman’s obits will probably lead with The French Connection.

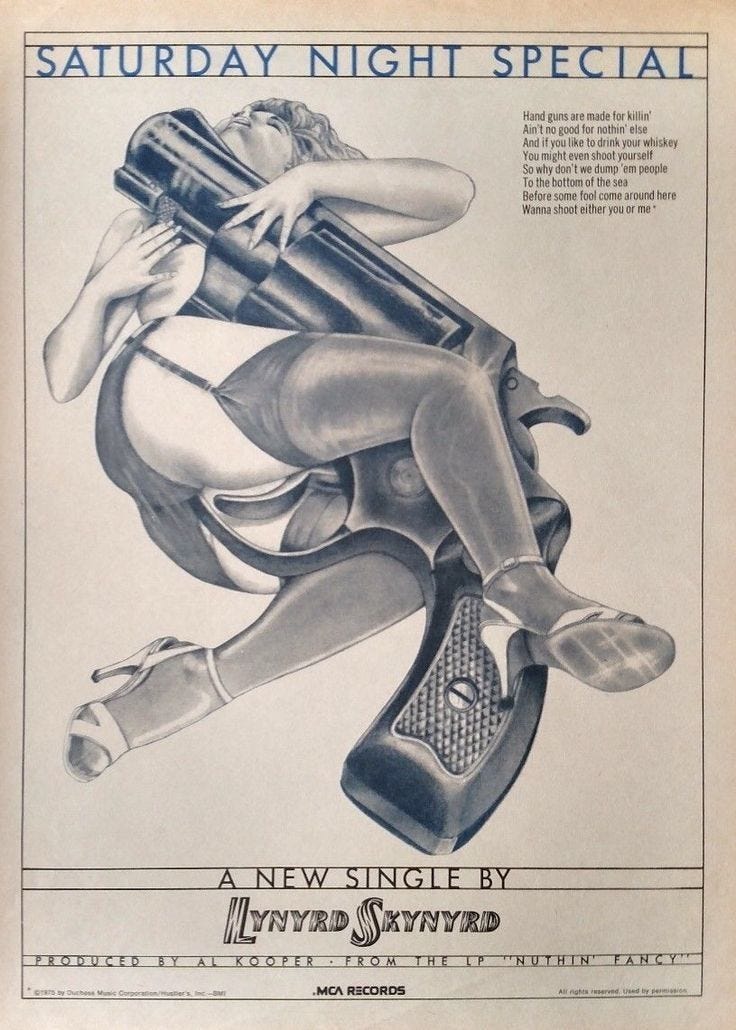

The pop culture of the 1970s brought us plenty of other anti-gun intellectual properties. Among these is the song “Saturday Night Special,” released by Lynyrd Skynyrd in 1975. The title refers to the type of cheap, poorly made handguns that were supposedly popular among the kinds of thieves that knocked over gas stations and liquor stores without much of a plan. The song is a plea for gun control and an argument that street weapons like the Saturday night special “ain’t good for nuthin/but put a man six feet in a hole.” The song goes on to say that:

Hand guns are made for killin’

They ain’t no good for nothing else.

And if you like to drink your whiskey

You might even shoot yourself.

What’s curious about this is that Lynyrd Skynyrd was a testosterone-driven Southern rock group (still are, in fact, though the personnel have changed dramatically through the years). The members of the band didn’t like to hear non-Southerners criticizing Southern culture. Their best-known song is an angry response to the Neil Young song “Southern Man.” Released just months before the resignation of President Richard Nixon, when every good liberal was obsessed with the Watergate scandal, “Sweet Home Alabama” contains a lyric that proclaims: “Now Watergate does not bother me/Does your conscious bother you?” These guys were the exact opposite of big-city liberals like John Ball and Laura Z. Hobson. It’s difficult to imagine a proud Southern redneck rock band recording a plea for gun control nowadays. But back in the 1960s and 70s issues like abortion and gun control and the Equal Rights Movement hadn’t become a clear dividing line between liberals and conservatives the way they are now. Liberals like Jesse Jackson and Al Gore embraced a pro-life platform until well into the 1980s, at which point they changed their tune in order to attract Democratic presidential primary voters. Likewise, George H.W. Bush was nicknamed “Rubbers” Bush, because for many years he was an outspoken proponent of Planned Parenthood. He switched his position only after Ronald Reagan chose him as his running mate in 1980. Republican President Gerald Ford and his wife Betty were vocal supporters of the ill-fated Equal Rights Amendment. That explains how Mac Davis, a native of Lubbock, Texas, could write a song like In The Ghetto, which became a hit, in 1969, for Elvis Presley, a native of Tupelo, Mississippi. The song is critical of gun culture, and also criticizes the way that so many African-Americans of the era were condemned to poverty. It remains an incredibly powerful indictment of guns and poverty and, implicitly, racism. Nothing quite like it has come from Southern good-ole-boy culture in quite some time.

One of the earliest Hollywood films to deal with the post WWII rise of gun violence in the U.S. was Peter Bogdanovich’s 1968 thriller Targets, which starred Boris Karloff and Tim O’Kelly and was produced by Roger Corman. The film was inspired by the real-life killing spree of Charles Whitman who, in August of 1966, climbed to the top of a clock tower on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin and used a variety of weapons to fire upon the people down below. The shooting spree lasted 98 minutes and claimed the lives of fourteen people (including an unborn child). An additional 31 others were seriously injured during the spree, including one who would die years later from his wounds. Two Austin police officers finally brought the spree to an end by shooting and killing Whitman. Like a lot of other deadly rampages, Whitman’s started out with an act of domestic violence. Even before leaving for the UT campus, he stabbed both his mother and his wife to death. In Bogdanovich’s film, Boris Karloff plays Byron Orlok, an aging horror-movie actor who has decided to retire. Tim O’Kelly plays Bobby Thompson, a young Vietnam War veteran who lives in Los Angeles with his wife and his parents. One day, like Charles Whitman, Bobby Thompson snaps. He murders his wife and mother and then goes on a killing spree that eventually ends at a drive-in movie theater where Karloff’s character is making a final public appearance. It was probably the first American film to capture the phenomenon of the motiveless mass murder who, thanks to a combination of mental illness and easy access to deadly weapons, guns down a large number of people in a short span of time. The film was completed before the assassinations of King and RFK but released just a few months afterwards. In 2020, director Quentin Tarantino wrote of Targets, “[F]orty years later it’s still one of the strongest cries for gun control in American cinema. The film isn’t a thriller with a social commentary buried inside of it (the normal Corman model), it’s a social commentary with a thriller buried inside of it…It was one of the most powerful films of 1968 and one of the greatest directorial debuts of all time. And I believe the best film ever produced by Roger Corman.”

In 1974, director John Badham made a curious TV film for the American Broadcasting Company called The Gun, which was an undisguised plea for sensible gun control in America (Curiously, three years after he directed The Gun, Badham struck cinematic gold as the director of Saturday Night Fever, a film that, despite the title, had nothing to do with handguns). The “star” of the TV movie is a .38 special handgun that gets passed around from owner to owner. The camera follows the gun as it comes off the assembly production line and then into the hands of various people. Some of them are law-abiding citizens. Some of them are criminals. The gun is used in the commission of several crimes but is never fired during any of these. Eventually the gun ends up in a scrap yard, where it is saved from destruction by a garbage man who brings it home with him after work. Weeks later, the man’s young son happens to find the loaded handgun hidden in his father’s room. Curious, he points the gun at his face. The screen fades to black. And then, at last, we hear the gun being fired as the film comes to an end. The film has become somewhat of a mystery. It was never re-run on television and has never been made available for home viewing on any platform or medium. Some fans of the movie have put forth conspiracy theories online about why the film seems to have vanished from sight. Most of these theories involve the NRA or a cabal of America’s major gun manufacturing CEOs who, having purchased the rights to the film from ABC, proceeded to destroy all copies of it. I’m sympathetic to this theory. The film was incredibly powerful. And, in keeping with the tradition of script recycling in American television, several popular TV programs have reused the central device of Badham’s film. Wikipedia notes that the Hawaii 5-0 episode titled “Diary of a Gun” and the Quincy, M.E. episode titled “Guns Don’t Die” contain plots very similar to the plot of Badham’s film. Though the film isn’t available for viewing any longer, copies of Michael T. Kaufman’s novelization of the film are available cheaply online. And that book is, if anything, more of a clarion call for gun control than the movie itself was. In addition to Kaufman’s novelization, the book contains a weird afterword from Richard Levinson and William Link titled “A Letter To Television Editors From the Producers of The Gun.” Best known as the creators of the TV series Columbo, Levinson and Link produced The Gun and co-wrote the script. Their afterword begins “ABC has asked us to write a note giving some background on our production of ‘The Gun’ — not only the history of the project but also how we feel about the completed film.” Why this is addressed to “Television Editors” and not general readers I cannot say. The novelization runs only about 115 pages long, so perhaps the afterword was written earlier as a part of a promotional package for the film and then tacked onto the book later just to give it the appearance of being longer. At any rate, the afterword directly addresses the issue of gun control. Levinson and Link note that, while working on a previous project, “we learned a disturbing statistic: there are an estimated 200 million guns in the United States, or about one per person for the entire population. [Nowadays the number is closer to 400 million.] After noting that guns are far too easily passed from one owner to another, they write, “The .22 caliber pistol that assassinated Robert Kennedy, for example, had actually passed through five hands, from 1965 to 1968, before it reached its tragic destination…The subject of guns, of course, is an emotional one. Legitimate gun owners, hunters, and collectors resent what they feel are governmental encroachments on their liberties. And yet, 20,000 Americans are killed each year by guns, many the victims not of criminals, but of accidents and domestic squabbles.” And yet that isn’t the end of the gun-control propaganda contained in the novelization. The book concludes with a long essay written by Michael J. Harrington who, at the time, was a U.S. Congressman from Massachusetts. His essay had been previously published in The Nation, a left-leaning national affairs magazine. Harrington’s essay is much longer than Levinson and Link’s and goes into greater detail about the difficulty of fighting for gun-control against the National Rifle Association’s Washington, D.C., lobbyists. He notes that even the mildest gun-control legislation, such as efforts to require that all guns be registered with the government, face ferocious opposition from the NRA. He mentions a number of moderate lawmakers who have been voted out of office after running afoul of the NRA and its propaganda machinery. He also notes that, “In 1968, after the shock of the assassinations, former astronaut John Glenn chaired an ‘Emergency Committee For Gun Control’ composed of people like Warren Beatty, Truman Capote, Joe DiMaggio, Vince Lombardi, and Archibald Cox.” He ends on a positive note, pointing out that plenty of ordinary Americans could probably be brought around to support the gun-control position if the argument is made properly to them. “These people have been grief-stricken by the assassinations of the last decade, believe in the responsible use of firearms, wish to be free of the fear of crime, and want to trust their government.” Harrington seems to believe that there is plenty of common ground to be found between liberal and conservative Americans on the subject of guns. Alas, time would prove him to be tragically wrong about that.

If Targets was the best gun-control movie to come out of the 1960s and 70s, and “Ohio” the best song, then my vote for the best novel of the gun-control genre goes to Glendon Swarthout’s The Shootist, published in 1975. It’s the story of John Bernard Books, a notorious Old West gunman – or “shootist” – who rides into El Paso, Texas, one day in January of 1901 and takes a room at a boarding house owned and operated by a widow named Mrs. Rogers. Books has been feeling poorly and he calls upon Doc Hostetler, a local physician, to diagnose his problem. The doctor examines Books and then tells him that he has an advanced case of prostate cancer and can’t expect to live more than another month or two. Resigned to his fate, Books goes about getting his affairs in order. The novel upends many of the romantic contrivances of the traditional Western. The gunman here isn’t a young buck like the Sundance Kid or Billy the Kid. In fact he isn’t a kid at all. He’s an old man dying miserably of cancer. And Swarthout doesn’t spare us the details. Hostetler tells Books, “When I examine you rectally I find a hard, rocklike mass spreading laterally from the prostate gland to the base of the bladder to the rectum.” When Books asks him how the disease progresses, Hostetler tells him: “The bones of the face become prominent. The skin takes on a grayish cast. You will be a pretty awful sight…There will be increasing severity of pain. In the lumbar spine, in the hips and groins…Your water will shut off progressively. The bladder will swell because you can’t unload it. You will gradually become uremic. Poisoned by your own waste products due to a failure of the kidneys. By this time the agony will be unbearable, and no drug will moderate it. Hopefully, you will become comatose. Until you do, you will scream.”

What’s interesting here is that both the cancer that is killing Books and the various gun deaths that occur in the novel are always described in great clinical detail. It is clear that Swarthout is equating gun violence to cancer. And, like prostate cancer, gun violence is a particularly masculine disease. Here is how a shooting is described in a typical Louis L’Amour Western:

Whipping around at the first sound, I fired the shotgun point-blank at the nearest man; then, forgetting the other barrel, I caught up the pistol and shot into the next man…I fired again, and that man went down. He got up, staggered a few steps, and fell again.” (from The Lonesome Gods)

Here are some of the shootings described in The Shootist:

Serrano had sent a bullet through Jay Cobb’s rib cage from the right side at a distance of nine feet. After encountering bone and entering the chest cavity anteriorly, the slug tumbled through the lower lobe of the left lung, macerating it, before exiting posteriorly through the rib cage on the left side, tearing an exit wound the size of a fist. With such force was the round driven into and through and out of the body that bits and pieces of bone and shirt were found adhering to the rear wall mural the following day, together with gobbets of lung tissue, pink and gray in color…Cobb had incurred what doctors call a “sucking wound.” He had hauled himself to his hands and knees, and since one lung had collapsed, the macerated left, as he breathed laboriously by means of the right lung, air was drawn loudly through the gaping aperture in his left rib cage.

The bullet was fired from above and from the rear, an oblique trajectory, at a range of seven feet. It penetrated the temporal bone above and forward of the ear, exposing the brain, passed through the brain, carrying with it segments of skull, and exited through the right orbit, or eye socket, taking off the ethmoid plate and the bridge of the nose. On the tile floor under what remained of Jay Cobb’s face lay an eyeball and the brain matter which housed the accumulated knowledge of his twenty years…

His round has entered Jack Pulford’s white silk shirt near a diamond stud slightly to the left of the sternum, or breastplate, and torn through the atrioventricular groove. The heart was literally cleaved in two. Yet there was no exit wound in his back, for the heart muscle, tough and fibrous, poses a real impediment, even to a bullet.

His bullet totally smashed Serrano’s globe, or eyeball, spattering the floor and bar and locker doors with the gelatinous substance of the eyeball. Slivers of bone were driven by the round through the brain, and a triangle of skull and hair was lifted out at the exit wound in the occipital area.

Again and again, Swarthout forces the reader to witness just how truly grisly a gun death can be. Unlike L’Amour and most other Western novelists, Swarthout doesn’t let you look away. This is a technique that is just now catching on among contemporary journalists who write about gun violence. On June 1, Charlie Sykes wrote an article for the online journal The Bulwark called “What the AR-15 Does to a Child’s Body,” which begins this way:

What if we saw the pictures?

At the moment, the question is academic, since no one can really bear the thought of seeing them. But what if we saw the pictures of children blown apart by America’s most popular gun?

To the best of his ability, Swarthout, back in 1975, was showing us the pictures of what gun violence looked like up close. Alas, his method didn’t really catch on. Most Western novelists continued, like L’Amour, to describe gun deaths in a fairly bloodless manner. A man is shot. He falls off his horse. And is dead by the time he hits the ground. Nobody needs to know about sucking wounds and gelatinized eyeballs. But Swarthout was trying to tell us that gun violence is a cancer on our culture. And not just any cancer, but a specifically masculine one. And, as if to show just what assholes those who kill with guns can be, rectums figure again and again in the plot. At one point, Books shoots a would-be assassin who has snuck into his rented room to kill him. The wounded man turns and tries to go head first out the window before Books can fire again. The effort fails:

Raising the Remington over the blazing bedclothes, Books sighted on his enemy’s rectum…He fired. Ranging half the length of the spine, shattering vertebrae and destroying the central nervous system, the .44 slug drove the body halfway through the window.

A few moments later, when landlady Mrs. Rogers enters the room, she sees the victim, who “seemed to be attempting to climb out of the south window, out of the house. But he was still, his legs spraddled wide. And from between his buttocks, through the denim of his pants, a dark stream welled as though he were excreting blood.”

For roughly a decade after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, a handful of radicalized novelists, filmmakers, and songwriters tried to waken Americans to just what a cancer gun violence was on our society. But they were spitting into the wind. One of the most popular TV crime dramas of the era was Mannix, about a rugged L.A. private eye played by Mike Connors. The Washington Post once calculated that, over the course of its eight-year run (1967-75), Joe Mannix was shot seventeen times and knocked unconscious fifty-five times. He was also run over by all manner of vehicles (including, once, a dune buggy), forced to jump from a cliff, and subjected to a wide variety of other violent acts. But, of course, none of these encounters left him with any lasting scars or disabilities. The most popular film franchises of the era included the Shaft series and the Dirty Harry series, both of which fetishized gun violence. And one of the most iconic films of the era, 1974’s Death Wish, which starred Charles Bronson, perpetuated the myth that all it takes to stop bad guys with guns in a good guy with a gun. All of these films celebrated the violence they pretended to abhor.

Since 1968, other prominent American politicians have been shot by gunmen. But thanks to improvements in emergency medicine (much of it developed by doctors who served as field surgeons during the Vietnam War), President Ronald Reagan, Congressman Steve Scalise, and Congresswoman Gabby Giffords survived their assassination attempts (though Giffords suffered serious brain damage which ended her political career). After the deaths of MLK and RFK, a lot of American gun-control advocates allowed themselves to become optimistic about the possibility that the country might finally address the problem seriously. But it never really happened. Congress has passed numerous gun-control bills since the 1960s, but those laws have done nothing to reduce the number of guns in circulation. After the 2017 Las Vegas hotel shooting in which a 64-year-old man opened fire on a crowd of people, killing sixty and wounding 411, I foolishly believed we had probably reached a moment in time in which it would now be impossible for American lawmakers to continue to put off serious reform of our gun laws. But, of course, I was wrong. Some people think the turning point is nigh because of the recent racially-motivated murders of ten people in a Buffalo supermarket, and the subsequent shooting at a Uvalde, Texas, elementary school that took the lives of nineteen children and two adults. But I seriously doubt it will happen.

Ordinarily, politics may be downstream of culture. But gun violence in America is more than a stream; it is a river of blood. And it seems likely to roll on forever.