WANDA AND MARIA: A TALE OF TWO STORMS

One of my favorite websites is called Reading California Fiction. It is hosted by Typepad and was written entirely by my friend Don Napoli. Sadly, Don died at age 79 in early 2021. The site is no longer updated. I don’t know if anyone has archived it. It lives on for now but may vanish at any time. Don was a native of Michigan who came to California in 1960. He found himself working at the State Library in Sacramento. When he informed one of his supervisors that he really didn’t know much about California, the supervisor suggested he try reading Raymond Chandler’s books. Don followed this advice and became hooked on California fiction. He made it his mission to read as much California fiction as possible and write about it for posterity. Reading all of the fiction ever written about the Golden State would have been impossible, however, so Don set a few limits on his project. He decided he would write only about books that had been written before 1960, were set in California sometime between 1890 and 1959, were readily available in at least 800 libraries worldwide, and were written by authors who had lived during the era their novels described (in other words, he wasn’t interested in a historical novel set in 1890s Los Angeles but written by someone born in 1910). Don cheerfully admitted that his parameters were fairly random. If I tried to get him to write about Jessamyn West’s brilliant novel The Life I Really Lived, which was published in the 1970s but set, partially, in the Southern California of the 20s and 30s, he would simply laugh off the suggestion. He had his rules and he followed them to the letter. I miss Don a lot but browsing through his website and reading some of the hundreds of reviews posted there always makes me feel as if he is still around somewhere, still reading and writing about California.

Don’s website has a section called The Famous Fifty, in which he reviews fifty of the most famous California fictions that fall into his parameters. These are not necessarily the best fictions ever written about California. Indeed, Don greatly dislikes some of these books, such as Aldous Huxley’s After Many a Summer Dies the Swan and Norman Mailer’s The Deer Park (I share his dislike of both books). Don was a librarian, and he measured the “fame” of a book by how many copies were in circulation in the world’s lending libraries. He had access to this info at his fingertips. So do I, I suppose, but I haven’t really learned how to use WorldCat or any of the other online catalogs of the world’s library holdings, so I simply trust Don’s judgment on matters of fame. Number thirty on Don’s list is George R. Stewart’s 1941 novel Storm. The books on Don’s list are ranked by the number of libraries that carry a copy. Thus, both Huxley’s After Many a Summer and Mailer’s The Deer Park rank slightly ahead of Stewart’s Storm. Don breaks the Famous Fifty into five groups of ten books and then offers a comment on each group. Of the books ranked between 21 and 30, he writes, “What Makes Sammy Run and Storm are must-reads. The three short-story collections (Cress Delahanty, The Pastures of Heaven and The Pat Hobby Stories) are all excellent choices for readers who like their fiction in small chunks. Of the Chandler books, Farewell, My Lovely may be a bit sharper than The Lady in the Lake. The two remaining novels, After Many a Summer Dies the Swan and The Deer Park, should be avoided.”

I bought a copy of Storm years ago on Don’s recommendation, but only this year did I finally get around to reading it. Stewart was a firebrand academic who taught for many years at U.C. Berkeley. In the 1940s he refused to sign a loyalty pledge which the State of California was requiring all professors at state-run colleges to sign. He wrote about this experience in a book called The Year of the Oath: The Fight For Academic Freedom at the University of California. He published many books, and his worked covered a wide variety of subjects. One of his most famous books, Ordeal By Hunger, isn’t reviewed on Don’s blog because, although written like a gripping thriller, it is a true historical account of the tragedy of the Donner Party. Another of his best-known books is an historical account of Pickett’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. Probably his most famous work is the 1949 post-apocalypse novel Earth Abides, which is regarded as a classic of science fiction. Storm, as the title notes, is about a giant storm that germinates in Siberia but doesn’t fully form until it is somewhere off the coast of Japan, after which it gradually gains strength as it moves inexorably towards California. Stewart’s storm will drench all of California but the book focuses mainly on the damage it does to Northern California, specifically the mountainous region near Lake Tahoe and the Sacramento Valley that lies below it. Storm is somewhat of an experimental novel as its main character is, essentially, the storm. The book has human characters – a meteorologist for the state, a dam superintendent, a telephone lineman, etc. – but they all play minor roles and many are not even given names. The only real character is the storm itself. It is huge and it is powerful and it has the potential to take thousands of human lives as it starts pounding the northern Sierra Mountain range with snow and rainwater that could sweep away much of Sacramento, but Stewart doesn’t portray it as evil or malicious. It is a creature of nature, like a lion or a shark, and it is only doing what comes naturally to it. Stewart’s book was written before the construction of the Folsom Dam, which was completed in 1955. Since then, the dam and a series of levies constructed along the banks of the American River have protected the City of Sacramento from the kind of catastrophic flood that threatens it in Storm. Nonetheless, Sacramento still remains vulnerable to flooding. And a failure of the dam or the levy system during a heavy storm would probably prove as devastating to Sacramento as Hurricane Katrina was to New Orleans. Since I live in the very heart of the City of Sacramento I found Storm quite compelling and, at times, even terrifying. I am not sure, however, that I would recommend it to the average fan of popular fiction. The book contains all sorts of ruminations on soil erosion, cloud formation, zoology, geology, ecology, and many other subjects that tend to distract the reader from the thriller aspects of the narrative. Stewart had a lifelong fascination with American place names. In fact, he wrote several books on the subject, including Names on the Land (1945) and A Concise Dictionary of American Place-Names (1970). This interest in place names is on display in Storm. At one point he simply lists the names of the dozens of smaller creeks and streams that feed into the American River. This list meant something to me, because I am familiar with many of these creeks and streams. I have kayaked on even some of the most obscure of them, such as Slab Creek. But unless you have a fascination with the names of Northern California’s small waterways, you may find lists like this to be a bit tedious. Storm is one of those rare novels that actually have profound real-world effects. According to Wikipedia, the success of the novel helped popularized the practice of giving (usually feminine) names to tropical storms, which is now commonplace throughout the U.S. (although, since the late 70s, the names are just as often masculine as feminine). A meteorologist in the book christens the titular storm “Maria” (pronounced ma-RYE-uh, according to a note by Stewart), a fact that inspired the songwriting team of Alan J. Lerner and Frederick Loewe to write a song titled “They Call the Wind Maria” for their 1951 Broadway musical Paint Your Wagon, which is set in Northern California’s Gold Country. The song has since become a staple of both American show tune catalogs and folk music catalogs.

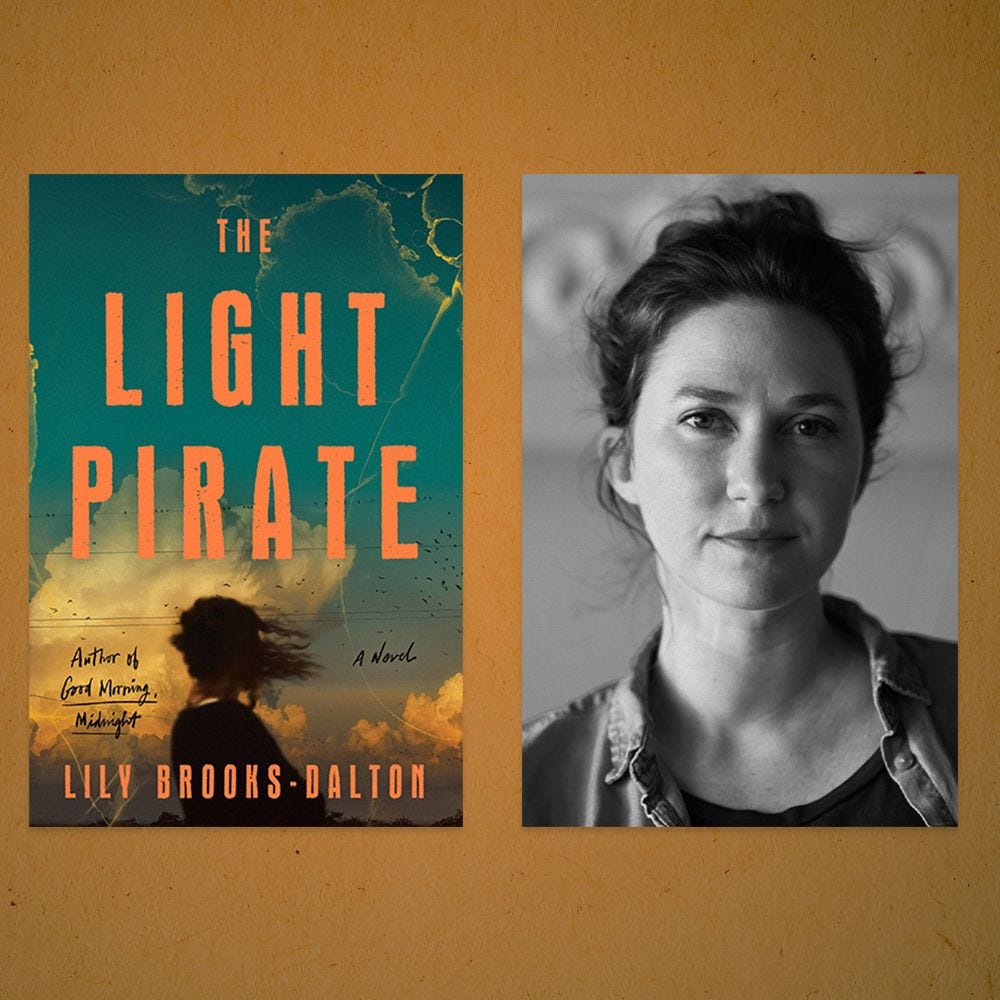

Another reason why I enjoyed Storm has to do with my lifelong love of bad weather. I grew up in Portland, Oregon, which is known for its frequent rain showers. I once thought of compiling a list of all the great rainstorms in popular novels. The list would include the chapter in Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield called “Tempest,” in which he describes a great storm that envelops the narrator and his environs as he takes a carriage ride from London to Yarmouth. I remember also being thrilled by the storm that floods the streets of Los Angeles in chapter eleven of James M. Cain’s Mildred Pierce, making it nearly impossible for the book’s heroine to reach Pasadena. Storm rekindled my desire to read about bad weather, so I went online to search for novels specifically about storms. My search led me to The Light Pirate, a 2022 novel written by Lily Brooks-Dalton. The author’s first novel, 2016’s Good Morning, Midnight, was made into a 2020 film called The Midnight Sky, starring and directed by George Clooney. I saw The Midnight Sky on NetFlix when it first came out and, with some reservations, liked it. Thus I was intrigued when I learned that the author of the film’s source material had recently published a novel about a massive storm that permanently alters the landscape of Florida. I got hold of a copy of The Light Pirate a few days ago and yesterday – Thursday, April 4 – I began reading the book at about nine a.m. It proved so fascinating and compelling that I sat up in bed until eleven p.m. reading all the way to the book’s conclusion. It is a book with many twists and surprises, and I don’t want to give away too many of them, so this review will, of necessity, be somewhat cryptic. The book takes place in and around the fictional town of Rudder, Florida, and begins in roughly the present day. The first character we meet is a young married woman named Frida, who is nine-months pregnant. Her husband, Kirby, has been married before and currently has custody of his two sons, Lucas and Flip. The third hurricane of the season is bearing down on Rudder, and Frida is wishing that Kirby would drive her and the boys to safety, somewhere far from the coast. But Kirby is a lineman for the local public utility. His job requires him to be available for emergency power-line repairs when storms are threatening. What neither Frida nor Kirby realizes is that, thanks to global climate change, the oncoming hurricane – named Wanda by the weather service – is going to be bigger and wetter and more powerful than any previous storm in Florida’s history. In fact, it will bring so much water with it that it will eventually render the Miami-Dade area uninhabitable by humans, leaving it permanently under several feet of water. During the hurricane Frida will be forced to give birth to her child at home, because the roads are unusable and Kirby cannot drive her to a hospital. They name the child, a daughter, Wanda, after the storm. As it turns out, Wanda (the girl not the hurricane) is the main, and titular, character of The Light Pirate. She grows up in a world vastly different from the world that you and I and Wanda’s parents grew up in. Technically, I suppose, The Light Pirate is a post-apocalypse novel. The rising waters and warming climate pretty much cause the entire state of Florida to cease to exist as a political entity. The U.S. government helps relocate the displaced citizens of Miami and other hard-hit parts of the state. Gradually, various local governments simply fall apart, and certain modern conveniences – cell phone service, electricity, natural gas, sewage systems, drinking-water systems – become extinct like dodos and carrier pigeons. Though climate catastrophe hits Florida first, the reader is led to believe that other parts of the U.S. and, indeed, the world are being similarly transformed. But we learn very little about these other catastrophes because the book remains rather relentlessly focused on Wanda the Light Pirate. Curiously, the Florida that Wanda inhabits didn’t strike me as a post-apocalyptic hellscape. In fact, in some ways it seemed kind of pleasant. With Disney World and Miami gone, the natural world has been allowed to creep back into the more Disneyfied parts of the state and reclaim some of its lost territory. The humans who remain living in and around the town of Rudder have no choice but to accept the primacy of nature over the man-made world. Within a decade or so, cars and other automated devices cease to be operable in Rudder, mostly because there is no gas or electricity to power them. The roadways are now mostly underwater, as are the first stories of many of the homes. The people get around by paddling about in canoes. In some ways, Rudder becomes a sort of watery Eden. But, as in every paradise, there is a serpent in this one. With governments gone and the schools all closed, and with everything else that binds a large human community together now just a distant memory, the people of Rudder and its environs have tended to split up into various tribal groups. Many of these are fairly harmless, basically just extended families. But some of the groups, as you might expect, are less friendly than others, and are given to preying on smaller and weaker groups. And this makes the job of eking out an existence in a water-soaked landscape, fraught to begin with, much more difficult and dangerous.

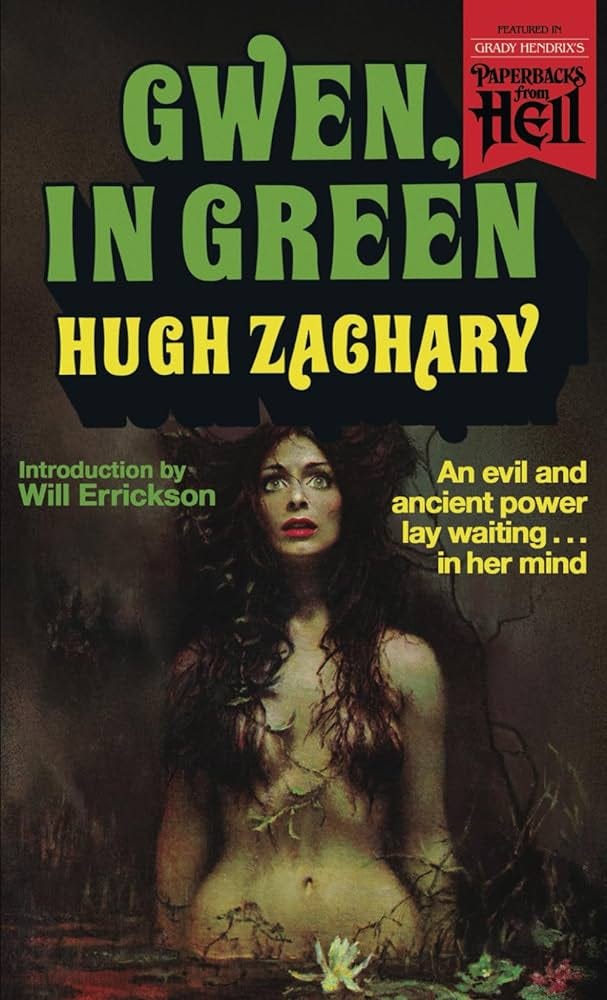

Curiously, Wanda, who seems to represent a new branch in human evolution, develops (or perhaps she was born with it) a supernatural power (suggested by her nickname) that is, unlike most fictional superpowers, of almost no practical use to her (in fact, it can sometimes put her in danger). This supernatural gift is interesting and beautiful to visualize, and it is undoubtedly meant as a metaphor for a new way of being a human in the world, a way that requires not conquering nature but living in harmony with it. The book reminded me of a novel I read earlier this year, a 1974 pulp horror novel called Gwen, In Green, written by Hugh Zachary. Both are set in swampy locations. Gwen, In Green is set in a swamp near the Cape Fear River in North Carolina. Both books have a feminist bent to them. Both are ecological parables about how women seem to be more in touch with the natural world than men are. The Light Pirate is an elegiac and lyrical literary novel. Gwen, In Green is a raunchy horror novel. But they seem to share quite a bit of swampy, feminist ground.

A large part of the The Light Pirate is devoted to simply creating the fictional world that Wanda inhabits. Brooks-Dalton also develops one or two other characters nearly as fully as she develops Wanda. Among these are an older woman named Phyllis and a girl about Wanda’s age who goes by the nickname Bird Dog. This is all interesting but not especially gripping. Fortunately, in the final third of the novel, the narration goes back and forth between the time in Wanda’s life when Phyllis was her most important companion and the time in which Bird Dog is her most important companion. As the narrative flashes forward and backwards we come to learn how it was that Bird Dog eventually replaced Phyllis in Wanda’s life. And these passages bring us some actual pop-fiction-like drama and action – a foray into an abandoned commercial district that evokes similar scenes from the 2018 film A Quiet Place, a shootout, an act of arson, an escape, a disastrous medical development. Brooks-Dalton does a masterful job of doling out information about the events that caused Bird Dog to eclipse Phyllis’s place in Wanda’s life. At the very end of the book, we jump much farther ahead in time, and we are allowed to see…well, you’ll have to read the book if you want to know what we are allowed to see. I will just note that I found the ending very moving and I had tears in my eyes as I closed the book.

The Light Pirate opens with this passage:

Somewhere west of Africa, so far from land the sky is empty in all directions, a storm begins. The water is warm, the waves are high. The air is heavy with moisture. A breath of wind catches, then circles back, churning itself into something new: a closed circuit gathering power, tighter and tighter. In this way, the storm grows.

Near the beginning of George R. Stewart’s Storm, we find this passage:

From Siberia the wide torrent of air was sweeping southward – from death-cold Verkhoyansk, from the frigid basin of the Lena, from thick-frozen Lake Baikal…The air at last swung away from the coast, and moved out over the sea; with every mile of passage across the water it grew more moist and temperate…Now the wind was no longer a gale, scarcely even a strong breeze. The polar fury was spent. But still, east by south, the river of air flowed on across the China sea toward the far reaches of the Pacific.

Both Brooks-Dalton and Stewart begin their narratives with a storm forming in a named place (Africa, Siberia). They describe the air and its movement. They describe the transformations that the storm undergoes as it leaves the place of its conception. Brooks-Dalton sends her storm northwest towards America’s east coast. Stewart sends his southeast, towards America’s west coast. But after that the two narratives diverge dramatically. Stewart’s remain relentlessly focused on a storm called Maria. But Brooks-Dalton’s switches its attention from a storm called Wanda to a girl who is named after the storm. Stewart’s book pays little attention to people and lots of attention to the natural world. Brooks-Dalton’s book pays attention to both people and the natural environment they inhabit. Stewart’s book is weirder and more experimental, less conventional. Brooks-Dalton’s book resembles many another post-apocalypse narrative, including, in some ways, Kevin Costner’s film Waterworld. Stewart’s is probably the greater literary accomplishment, but I enjoyed Brooks-Dalton’s book more than Stewart’s. Great storms can be awe-inspiring but by themselves they are not terribly moving or poignant. The Light Pirate is an oddity: an eco-novel, a literary novel, and a pop-fiction thriller all sort of rolled into one, and not always very seamlessly. Sometimes the eco-novel seems a bit preachy. Sometimes the literary novel seems a bit flowery. And sometimes the pop thriller seems a bit melodramatic. The Light Pirate is one of those legions of intellectual properties – movies, books, TV shows, etc. – that are successful not just in spite of their flaws but almost because of those flaws. If Brooks-Dalton hadn’t been so ambitious, if she had focused, say, on just giving us a very literate novel of ecological disaster, the book might have been well-reviewed but quickly forgotten. Instead, she gave us a somewhat awkward mashup of various literary styles and genres and left us, instead, with something memorable and moving.

My late friend Don Napoli would most likely recommend Storm more highly than he would recommend The Light Pirate. I recommend The Light Pirate more highly than I do Storm. But you don’t have to choose between them. You’re free to read them both, to make friends with both Wanda and Maria. Lucky you.