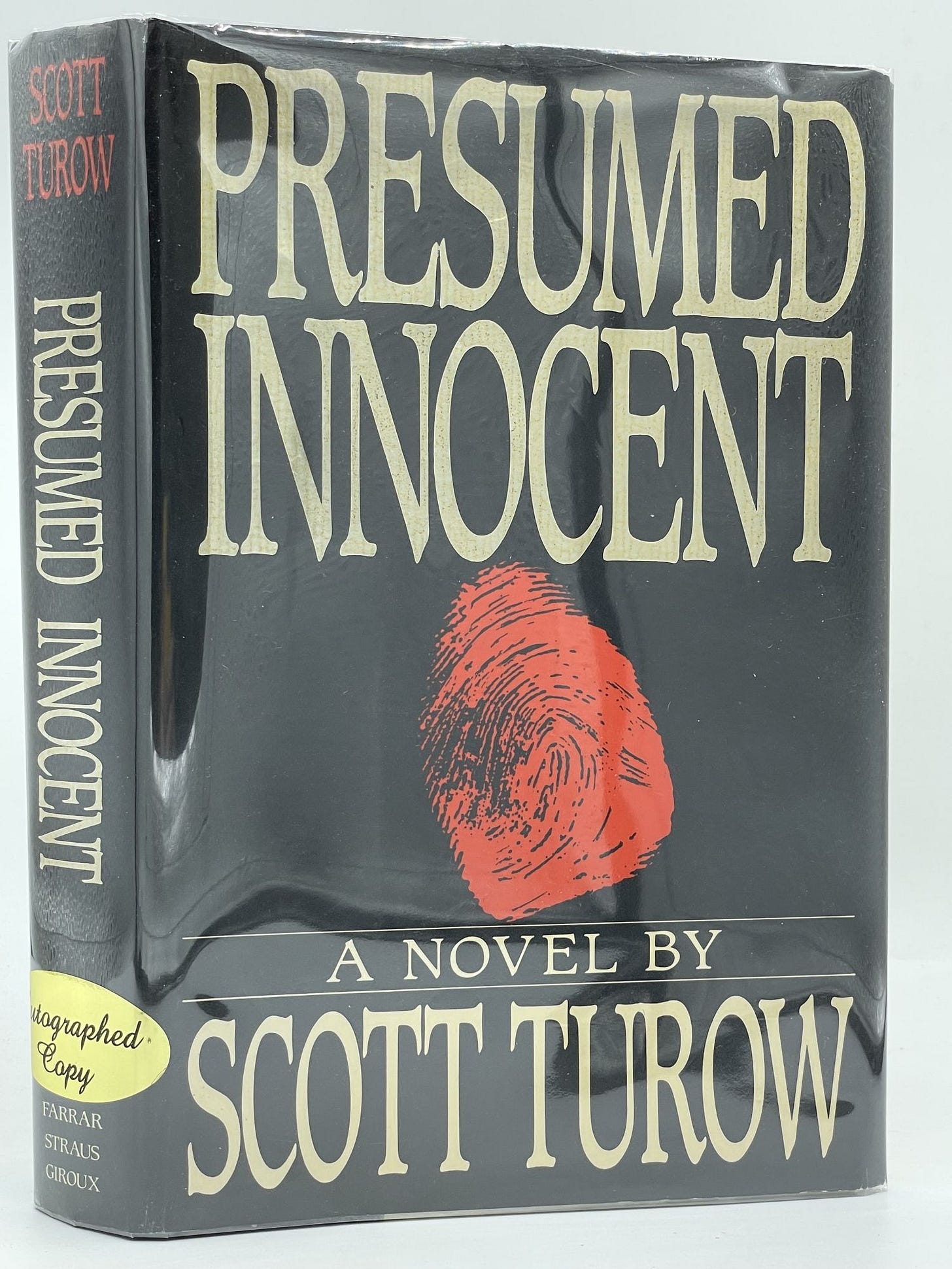

Presumed Innocent, a new Apple-TV miniseries starring Jake Gyllenhall, is based on a 1987 Scott Turow novel of the same name which many pop culture authorities credit with kickstarting the modern fiction genre known as the legal thriller. The book was a huge success even before it was published. It earned advance praise from the likes of Wallace Stegner, who attested to its literary quality, and Vincent Bugliosi, who attested to its authenticity. It became the seventh bestselling novel of 1987, outselling titles by Stephen King (whose Eyes of the Dragon finished in tenth place), Louis L’Amour (whose The Haunted Mesa finished in eleventh place), and even Tom Wolfe (whose Bonfire of the Vanities finished in twelfth place). In 1990, Warner Bros. brought out a film adaptation directed by Alan J. Pakula (To Kill a Mockingbird, All the President’s Men) and starring Harrison Ford. The film was a smash at the box office, earning ten times its production budget.

Presumed Innocent was Turow’s first novel, but ten years earlier he had published a successful nonfiction book, One-L, about his first year as a student at Harvard Law School. He followed up Presumed Innocent in 1990 with The Burden of Proof, which was a sort of sequel to his first novel and is set in the same fictional Illinois County – Kindle, a stand-in for Cook County, home of Chicago – and reuses some of the same characters as Presumed Innocent. In the 34 years since the appearance of Burden of Proof, Turow has published an additional eleven novels, all of them tied to Kindle County in one way or another. But Turow has long since lost his luster as an author of mega-bestsellers. In 1991, another lawyer-turned-novelist, John Grisham, published a novel (his second) called The Firm. It became a runaway bestseller, finishing in seventh place among the year’s top selling novels, right alongside such household names as Stephen King, Danielle Steel, Tom Clancy, Dean R. Koontz, and Ken Follett. Unlike Turow, Grisham never relinquished his role as the King of the Courtroom Thrillers. The bestselling American novels of 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, and 2000 were all written by Grisham. In 2001, he fell all the way to second place, with Skipping Christmas, but he was right back on top the following year with The Summons. He continues to turn out hugely successful legal thrillers as well as novels in other categories, such as YA, humor, mystery, etc. Grisham and Turow are sort of the Hammett and Chandler of the American legal thriller. Turow, with his undergraduate degree from Amherst, his fellowship from the Stanford University Writing Program, and his law degree from Harvard is often thought of as the thinking-man’s thriller writer. Grisham, with his undergraduate degree from Mississippi State University and his law degree from the University of Mississippi tends to be looked down upon by serious literary critics as a writer of mere page-turners. But he is definitely the People’s Choice. He has written 37 consecutive books that have reached the number one spot on the New York Times’s weekly fiction bestsellers list. His books have sold more than three hundred million copies. And at age 69 (six years young than Turow who is still active as a writer) he remains as prolific as ever.

I have complicated feelings about both authors. I really liked Presumed Innocent and sorta liked The Burden of Proof when they first came out more than thirty years ago. But after that I felt that Turow’s books became too self-serious, as if he were trying to turn Kindle County into Yoknapatawpha County and become, not the Hammett of the legal thriller but the Faulkner of that genre. And the results tended to be mixed at best. With 1996’s The Laws of Our Fathers, Turow’s longest novel at 832 pages, he seemed to want to write The Great American Baby Boomer Novel. It is a complex and, at times, even convoluted story that goes back and forth from the present to the Vietnam War era, and Turow seems to be trying to capture every aspect of life in his generation of Americans. I admired the ambition but the book was a slog to get through. In Presumed Innocent, the narrator, Rusty Sabich, says of his ambitious colleague Carolyn Polhemus, “I suppose I thought she was just a little bit too much…Too much everything. You know. Too bold. Too self-impressed. Always running one gear too high. She didn’t have the right sense of proportion.” That pretty much sums up how I began to feel about Turow’s work. He was striving to be Faulkner when he should have just been striving to be a better writer of legal thrillers. After The Laws of Our Faulkners – oops, Fathers – he was no longer a must-read for me. Some of his books I read. Some I let pass. It depended upon how long they were and whether I could find a cheap used copy.

As for Grisham, I was a big fan of The Firm. My father, a CPA, was in the hospital for prostate surgery when I was reading The Firm. I passed the book on to him, because the story deals with tax fraud and money laundering and other subjects I thought might interest a bedridden CPA with time on his hands. My father loved the book, and I sat in his hospital room talking with him about it for an hour one day. It was the only time I ever discussed a work of popular fiction with my father. He wasn’t a reader of novels. He mostly read newspapers and magazines related to the business world. My mother was the pop-fiction fan of the family. I acquired that love from her. But Grisham’s novel is firmly planted in my heart because it was the only book my father and I ever shared a love of.

Alas, after that, my experience with Grisham’s fiction was sort of uneven. He produced a lot more work than Turow did and his weaknesses were the opposite of Turow’s. The books sometimes had a rushed quality about them. The writing wasn’t always that crisp. Nonetheless, if forced to choose, I’d rather spend a year reading nothing but Grisham’s books than a year reading nothing but Turow’s. I admire both men, but Grisham seems more comfortable wearing the mantle of pop-fiction megabestseller. His books seem designed to be crowd-pleasers. Turow’s seem designed to be critic-pleasers. In this instance, I’d rather be with the crowd than the critics. But it still leaves us with the question of why Presumed Innocent has become recognized as the book that created the modern legal thriller. Plenty of novels about lawyers and courtrooms were published prior to Presumed Innocent. And many of those novels were written by lawyers. Erle Stanley Gardner, a member of the California State Bar, wrote approximately 80 novels about defense attorney Perry Mason. He also wrote a lot of other novels with legal themes. Michigan Supreme Court Justice John D. Voelker’s Anatomy of a Murder (published under the pseudonym Robert Traver) is a highly authentic tale about a murder trial, and it became the second bestselling novel of 1958. Six years earlier, Herman Wouk’s tale of a military court-martial, The Caine Mutiny, was the second bestselling novel of 1952. Both Murder and Mutiny became hugely successful Hollywood films. Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder, starring James Stewart, was the tenth highest grossing film of 1959. Edward Dmytryk’s The Caine Mutiny, starring Humphrey Bogart, was the second highest grossing film of 1954. Plenty of other high-profile legal tales became bestsellers: James Gould Cozzens’s By Love Possessed was the bestselling American novel of 1957. Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird was the third bestselling novel of 1961. Louis Auchincloss’s The Embezzlers was the ninth bestselling novel of 1966. Taylor Caldwell’s The Testimony of Two Men was the fifth bestselling novel of 1968. Leon Uris’s QBVII was the sixth bestselling novel of 1970. The list goes on and on, but none of these books is ever credited with having created the modern idea of a legal thriller.

Vincent Bugliosi, who blurbed Presumed Innocent, wrote the most commercially successful true-crime legal thriller of all time, 1974’s Helter Skelter. In 1981 he co-wrote, with Ken Hurwitz, a novel called Shadow of Cain. Like Presumed Innocent, its leading characteristic is the authenticity of its legal details. To me, it is every bit as good as Presumed Innocent, and maybe even better. It is shorter and terser, but packs the same wallop. The book’s main character went on a killing spree as a high school senior and murdered several of his classmates. Twenty years later, because he was a minor when he was convicted, he is released on parole. The story is largely told from this killer’s POV, and Bugliosi even manages to make him fairly sympathetic, something you wouldn’t expect from the man who prosecuted Charles Manson. When people in the protagonist’s orbit begin to die, suspicion naturally falls on him. But Bugliosi and Hurwitz do a good job of keeping the reader guessing what the outcome of the story might be. I’m not sure why this novel didn’t become a bestseller. But it didn’t.

In 1977 Avery Corman published an iconic courtroom novel called Kramer Versus Kramer. Two years later it was adapted by Hollywood and became the highest grossing film of 1979. Curiously, this courtroom drama involved no crime. The novel details a custody battle between the mother and the father of a little boy. But the book generated a great deal of suspense and could certainly be described as a legal thriller if not a crime novel or a mystery. Corman wrote a phenomenally successfully courtroom drama a full decade before Turow did. Had he been a young, telegenic Baby Boomer he might now be remembered as the father of the modern legal thriller. But he isn’t. In 1992, after Turow and Grisham had made legal thrillers the hottest genre in popular fiction, Corman returned with another attempt at a blockbuster legal drama, a novel called Prized Possessions, about a girl trying to seek legal recourse against the school classmate who date-raped her. But this book turned out to be more bust than blockbuster. It failed to make the bestseller list and infuriated many feminist critics who felt that Corman had completely mishandled the subject of date rape, treating it as though it were a lesser form of rape.

John R. Feegel, who died in 2003, at the age of 70, had an impressive resume. He earned a law degree, a medical degree, and a masters in public health. In the 1970s he served as the medical examiner (coroner) for Hillsborough County, Florida, home of the city of Tampa. He also served for a while as an associate medical examiner in Atlanta, Georgia, where he testified in the trial of notorious serial killer Wayne B. Williams. Feegel’s 1976 novel, Autopsy, written in his spare time, won the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best First Novel. His interests included ancient Mayan culture, and he taught himself how to read the Mayan language. His obituary makes him sound like a cross between Quincy M.E. and Indiana Jones. But neither of those fictional characters was also an award-winning novelist. He wrote a textbook called Legal Aspects of Laboratory Medicine, and a total of seven novels. In 2022 I read his second novel, Malpractice, published in 1981 but set in the late 1970s. The novel makes excellent use of the author’s knowledge of both medicine and law, as well as his familiarity with small-town Southern culture. The reluctant hero of the novel is a young and inexperienced lawyer named Yancey Marshall, who practices in the town of Pine Hill, Georgia. His law office is just a cheap rented room above a drug store. One day he is visited by an impoverished Black woman named Eula Pitts. Her sixteen-year-old son Franklin Delano Pitts, an outstanding high school athlete, died recently during an appendectomy performed at the local hospital by a highly respected physician named Joe Thatcher. Ms. Pitts believes that Dr. Thatcher (a pillar of the white community) screwed up during surgery and that the hospital and the insurance company are covering it up. She wants Yancey Marshall to look into the matter. Marshall, for a variety of reasons (laziness, fear of stepping on the toes of powerful people, the knowledge that Ms. Pitts won’t be able to pay him much) tries to dissuade Ms. Pitts from pursuing the matter, but she won’t take no, and he eventually agrees to make a few casual inquiries. Fairly quickly Marshall uncovers a lot of dirty little secrets about his town. He learns, for instance, that Dr. Thatcher is a raging alcoholic and wife beater who often shows up drunk in the operating room. He learns that the small medical community is a tightly knit group of white people who tend to cover up each other’s mistakes. He also learns (although it isn’t really news to him) just how thoroughly racist the community is. The book has a lot in common with To Kill a Mockingbird. Both are set in the rural South. Both feature white lawyers fighting for the rights of Black people. Both are crime novels. Harper Lee was a better stylist than Feegel, but his prose, if not dazzling, is nonetheless rock solid. In some ways, you could say that Feegel’s timing was a bit off. Had Feegel published Malpractice in the early 1990s it might have been swept up in the mania for legal-thrillers that was a hallmark of American pop-fiction at the time. In fact, Feegel’s novel bears a strong resemblance to Grisham’s first novel, A Time To Kill, which was published by a small press in 1988 but didn’t become a bestseller until after The Firm made Grisham a household name. Alas, Feegel’s work never got much attention and is now mostly out of print. He’s another author whose courtroom dramas might have kickstarted the legal thriller craze if only they’d gotten the right kind of support from their publisher.

Another might-have-been father of the legal thriller was John Jay Osborn Jr. Born in 1945, Osborn was a Baby Boomer who published his first and most famous novel, The Paper Chase, in 1971. The book was a hit and it inspired an Academy Award-wing film starring John Houseman. Houseman also starred in a subsequent TV series adapted from the novel and the film. The Paper Chase isn’t really a legal thriller. It tells of the trials and tribulations of a first-year student at Harvard Law. It is, essentially, a fictional forerunner of Turow’s One-L. The novel was actually written while Osborn was a student at Harvard Law School. But after that, he wrote only four more novels over the remaining 51 years of his life, none of them a big seller. These were legal novels but not thrillers. He also wrote fifteen scripts for The Paper Chase TV series, as well as scripts for various other programs, such as L.A. Law and Spencer: for Hire. Mostly he focused on his career as a lawyer and law professor. But had he focused all his attention on producing bestselling novels, he might well have become the father of the modern legal thriller.

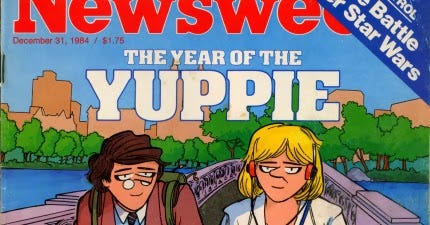

When Turow’s Presumed Innocent was published in 1987, Farrar Straus & Giroux could have promoted it as a “courtroom drama,” an appellation that had been applied to earlier bestsellers such as The Caine Mutiny or The Anatomy of a Murder. But, by the 1980s, “thriller” was the term of choice for the kind of books that were known to keep pop-fiction junkies sitting up all night in their armchairs. And so the publicity department for FS&G promoted Presumed Innocent as a “legal thriller.” It might not have been the first use of the term, but it was the first time the term was applied to a cultural juggernaut, a book that, in its way, would become as seminal as Rosemary’s Baby or The Day of the Jackal or Jaws. Four years later, when John Grisham broke into the big time with his second novel, 1991’s The Firm, the appellation was just waiting there to be exploited. Nowadays, of all the subgenres of thriller, the legal thriller is probably America’s most popular, thanks in large part to Grisham. But it was Scott Turow’s Presumed Innocent that gave birth to the genre. And it is still difficult to say exactly why that was. Perhaps it was his youth. Turow was only 38 when the book was published, roughly the same age as his protagonist. In his dust jacket photo, he looks even younger. No doubt it helped that he was well connected with establishment institutions like Harvard and Stanford. What’s more, Turow wasn’t a lawyer-turned-writer but rather a writer-turned-lawyer. He was a lecturer at Stanford’s prestigious Stegner writing program for several years before he switched career paths and enrolled at Harvard Law. It probably also helped that, when he began writing Presumed Innocent, he already had one published (non-fiction) book under his belt. What’s more, he was the consummate yuppie at a moment in time when yuppies were the masters of the universe – or at least of the American media ecosystem. A few years earlier, Newsweek had proclaimed 1984 to be “The Year of the Yuppie.” In case you’ve forgotten, yuppies were Young Upwardly-Mobile Urban Professionals. By rights, they probably should have been called “yumpies,” but the pundits were trying to connect the term to various previous double-P terms, such as hippies and yippies. All three terms essentially describe various stages in the evolution of the Baby Boomers (free-spirited anti-establishment types, organized leftwing political activists, status- and money-seeking corporate sellouts). Turow is, in many ways, a quintessential Baby Boomer: born in the late 1940s into an upwardly-mobile American household, he was in college in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the counterculture was at its peak; he got a premium education in a number of prestigious institutions before going to work in a top-tier profession and becoming well-off in the Reagan Era, when Greed is Good became a catchphrase for many people, especially yuppies. All of the above reasons may explain why it was Turow whom the media anointed the creator of a new genre, despite the fact that the genre had been around for as long as pop-fiction itself.

Turow (pictured above) had a couple of other things going for him too. In his book Bestsellers, scholar John Sutherland notes that the 1970s gave rise to the institutional bestseller, sometimes called the insider bestseller, a subgenre of pop-fiction that was written by people with actual insider experience with an especially interesting profession. He specifically cites the work of Joseph Wambaugh, who spent more than a decade as a member of the LAPD before he began publishing police novels, novels that provided a lot of details about police work that outsiders probably couldn’t have known about. Sutherland also mentions Michael Crichton and Robin Cook, two medical doctors who wrote, among other things, medical thrillers that often included a lot of seemingly hyper-realistic technical details about the medical profession. And he mentions Peter Gent, a former wide receiver for the Dallas Cowboys whose novel North Dallas Forty and its follow-ups provided readers with an inside look at what it was like to play in the National Football League. Likewise, former steeplechase jockey Dick Francis (and his uncredited wife Mary) wrote a lot of thrillers set in the world of professional horse racing. Institutional novels written by insiders existed before the 1970s (see the aforementioned Anatomy of a Murder) but the genre really began to blossom in the 1970s. Even Jaws was a form of insider novel, because Peter Benchley had a lifelong interest in sharks and oceans, had grown up in a seaside town, and written a lot about the natural world for National Geographic and other publications before tackling a novel about a great white shark.

The insider fiction trend became popular in the 1970s but no single author really stepped forth to take on the mantle of America’s best legal novelist the way that Wambaugh had seized the title of America’s best cop novelist or Robin Cook (Coma, etc.) had seized the title of America’s favorite author of medical thrillers. The closest anyone came was George V. Higgins who, like Turow, got a prestigious education and then a law degree and became a public prosecutor. In 1970 he published his first and best-known novel, The Friends of Eddie Coyle. It became a critical success and remains a milestone in realistic American crime fiction. The book, about Boston gangsters, exudes insider knowledge of the legal system and the criminal underworld. But it is not a courtroom drama. Neither were its immediate follow-ups, The Digger’s Game (1973) and Cogan’s Trade (1974). Only in the 1980s, with the arrival of his Jerry Kennedy series of courtroom novels, did Higgins become a candidate for the inventor of the legal thriller. But by then he had already been pigeonholed by the publishing industry as a writer of hardboiled Boston crime novels. Also, he was ten years older than Turow, and had lost his freshness by the time he had fully embraced lawyer novels.

Rereading Presumed Innocent recently, I found it somewhat slow and self-consciously literary. The author seemed hell-bent on finding new ways of describing every person, place, or thing in his story. This is an admirable ambition and sometimes it pays off. But a lot of the time it just acts as a drag on the story, like a parachute slowing down a hotrod (see what I did there?). He has an annoying habit of beginning paragraphs with a sentence that means nothing by itself: “But that, of course, begins to give way.” This occurs in a passage where Rusty Sabich is reviewing crime scene photos of his dead ex-lover who has recently been murdered. The previous paragraph ends with this sentence: “I urge myself to maintain professional composure.” At any rate, I’m going to quote the following paragraph in full because I think encapsulates Turow’s tendency towards pretentious writing that often becomes almost nonsensical.

But that, of course, begins to give way. It is like the network of crazing that sometimes seeps through glass in the wake of an impact. There is excitement at first, slow-entering and reluctant, but more than a little. In the top photographs the heavy glass of the table is canted over, compressing her shoulder, so that you might almost make the comparison to a laboratory slide. But soon it is removed. And here is Carolyn’s spectacularly lithe body in a pose which, for all the agony there must have been, seems initially, supple and athletic. Her legs are trim and graceful; her breasts are high and large. Even in death, she retains her erotic bearing. But, I slowly recognize, other experiences must influence this response. Because what is actually here is horrible. There are bruises on her face and neck, mulberry patches. A rope runs from her ankles to her knees, her waist, her wrists; then it is jerked tight around her neck, where the rim of the burn is visible. She is drawn back in an ugly tormented bow and her face is ghastly; her eyes, with the hyperthyroid look of the attempted strangulation, are enormous and protruding and her mouth is fixed in a silent scream. I watch, I study. Her look holds the same wild, disbelieving thing that so frightens me when I find the courage to let my glance fix on the wide black eye of a landed fish dying on a pier. I take it in now in the same reverential, awestruck, uncomprehending way. And then, worst of all, when all the dirt is scraped off the treasure box there is rising within, unhindered by shame, or even fear, a bubble of something light enough that I must eventually recognize it as satisfaction, and no lecture to myself abut the baseness of my nature can quite discourage me. Carolyn Polhemus, that tower of grace and fortitude, lies here in my line of sight with a look she never had in life. I see it finally now. She wants my pity. She needs my help.

We find a lot to unpack in that sentence. It is the kind of writing that undoubtedly dazzles the kind of people who make it into the Stegner writing program, but it doesn’t really have any business in a book that offers itself as a thriller. It contains some decent writing but it also contains some real head-scratchers. The paragraph’s second sentence is a simile comparing the faltering of the narrator’s composure to the way auto glass (I guess) begins to crack after an impact with a rock or something. All right, fine. But then almost immediately the narrator is talking about a glass-topped table in the crime scene photo, which is confusing. Was the reference to crazing glass meant to be a reference to the glass-topped table. But, no, in the next sentence the glass-topped table is compared to a laboratory slide, with the dead woman’s flesh being, I suppose, the material to be examined under a microscope. And why does he write “you might almost make the comparison to a laboratory slide,” when, in fact, he is doing exactly that? Why not just make the comparison? And then, suddenly, we get a description of the dead woman’s sexy body that seems to have come from a pulp crime novel of the 1960s. I’ve never really understood the concept of “high breasts,” unless it simply refers to breasts in a push-up bra or breasts that haven’t begun to sag yet. But it’s difficult to imagine what high breasts are when the body is dead and lying on the floor under a glass-topped table. Have they simply slid up towards the corpse’s chin? The reference to “large” breasts is easier to understand and it won’t be the last such reference, not by a long chalk. Meanwhile, Carolyn’s body, originally described as a laboratory specimen, is now described as a sort of hunting bow. And now we learn that her “erotic bearing” includes bulging eyeballs and a mouth frozen in a silent scream. Yummy. Shortly thereafter we are given a dead-fish simile. And then, out of nowhere, we are told that, “when all the dirt is scraped off the treasure box there is rising within, unhindered by shame, or even fear, a bubble of something light enough that I must eventually recognize it as satisfaction, and no lecture to myself abut the baseness of my nature can quite discourage me.” Where the hell did the treasure box come from? And what is it a metaphor for? It seems to be referring to the narrator himself, because rising within it are shame and fear and satisfaction, which can only be describing the narrator’s state of mind. But why would he describe his…psyche(?) as a treasure box, when it seems to contain nothing but unpleasant things? And, given the pulp fiction nature of the sexual descriptions contained in the paragraph, I couldn’t help wondering, at first, if treasure box was somehow a less crude synonym for snatch box. All of this rubbish writing appears in just a single paragraph of a 431-page novel that is filled with similar stuff. After re-reading only the first fifty pages of this book, I wanted to slap Wallace Stegner, a writer I highly admire, for praising Turow’s “marvelous control and touch.” Jeez. The above paragraph strikes me as totally out of control, with similes and metaphors – auto glass, lab slide, hunting bow, dead fish, treasure box – coming at the reader with no real rhyme or reason.

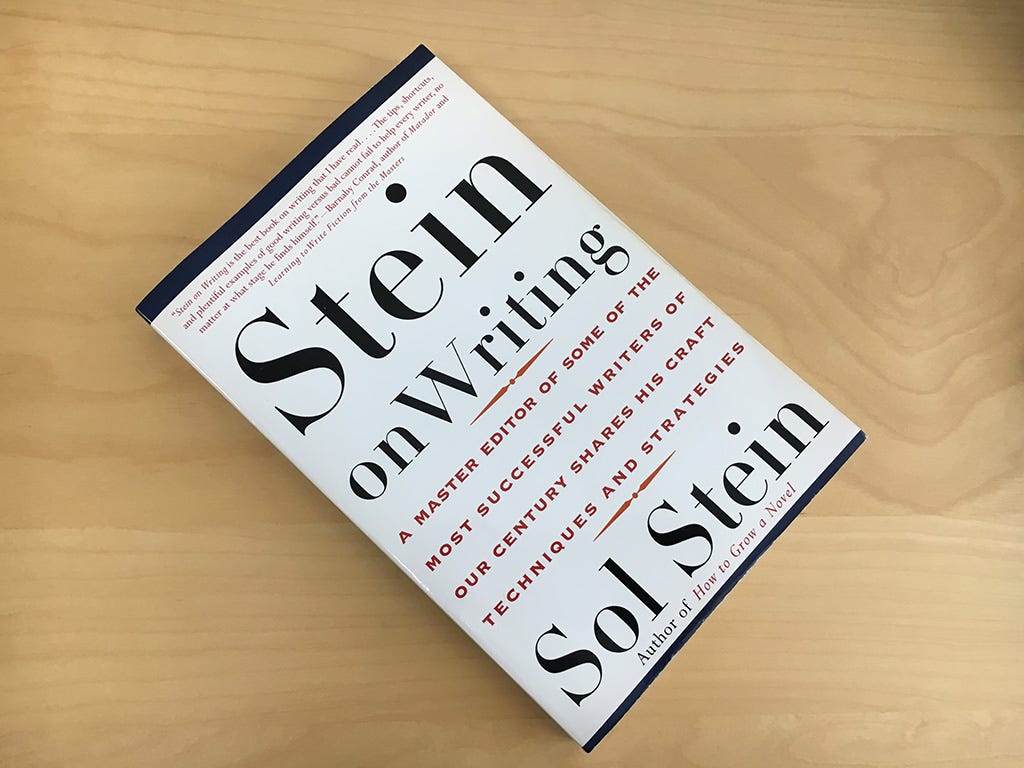

If Turow’s overwrought prose tends to be overpraised by the literary establishment, Grisham’s tends to be sneered at. In Stein on Writing, a craft manual written by the late Sol Stein, who was, among other things, the author of several failed legal thrillers, Grisham is singled out as an example of a bad writer. Stein writes: “I urge my students, once they have begun to master craft, to read a few chapters of John Grisham’s The Firm, or some other transient bestseller, to see what they can learn from the mistakes of writers who don’t heed the precise meanings of the words they use.” Grisham’s “transient” bestseller remains in print a third of a century after it was first published. It has generated over 20,000 reader reviews on Amazon.com, even though it was published long before Amazon reviews – or Amazon itself – were a thing. And it has a near-perfect 4.6 star rating. Sol Stein’s first novel, The Husband, has garnered 19 reviews and a 3.0 rating. None of his novels has generated even close to one hundred reviews at Amazon or Goodreads. Most of his books are long out of print, having proved not just transient but ephemeral.

I too have sometimes been disappointed in Grisham’s prose. But his mistakes are generally fairly ordinary ones, misplaced modifers, unclear referents, etc. And in my opinion, ordinary bad writing isn’t nearly as unendurable as literary bad writing. Grisham just wants to tell a good story and doesn’t seem to fuss much about the style of the writing. With Turow, the fussiness is the whole point of the writing. He wants you to know that he labored over this writing. Sadly, this fact is obvious to the reader, because it takes a great deal of labor to get through it.

When I re-read Presumed Innocent recently, what I found most surprising was just how sexist the main character seems these days. This wouldn’t have bothered me back in 1987. I probably didn’t even notice it. I’m hardly the most woke man in America. I don’t mind a little – or even a lot – of political incorrectness in a novel. Most novels are essentially reflections of their time, and Presumed Innocent is no exception. What bothered me about the sexism in Presumed Innocent was how badly written it was. With its emphasis on female breasts and buttocks and legs it often reads like the worst of John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee novels. Here’s Rusty Sabich describing Carolyn Polhemus to his shrink: “Very sexy. Torrents of blond hair, and almost no behind, and this very full bosom…You know: this very good-looking blond with big tits. Every copper who came in would roll his eyes and make like he was jerking off.” A page or two later he mentions, “her silk blouses, her red lipstick and painted nails, that large heaving bosom and her long legs.” Rusty seems obsessed with breasts. When we first meet his wife, he tells us that she is lying on her back, “breasts girdle in her sports bra.” I wouldn’t be bothered by any of this in a pulp paperback with no literary pretensions. But it annoys me that the cultural critics who hailed Presumed Innocence as a work of literature let this kind of writing pass without comment.

Elsewhere Turow’s writing possesses the standard political incorrectness of its time. He describes medical examiner Kumagai as “a weird-looking little Japanese who seems out of a forties propaganda piece.” It seems unlikely that Kumagai is Japanese. Most likely he is a Japanese-American. And we’re not told what is weird about his looks. Apparently being Japanese and little is enough to render him weird-looking in Rusty’s eyes. Anti-Japanese propaganda of the 1940s tended to portray the Japanese male as buck-toothed, squint-eyed, and wearing thick glasses. The racist cliché was still fairly common in the 1960s. See for instance Mickey Rooney’s godawful portrayal of Mr. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Or Vito Scotti’s buffoonish portrait of a Japanese sailor in a 1965 episode of Gilligan’s Island:

We could excuse all this if it Turow was using it to make Rusty look like a bigot, but that doesn’t seem to be his intention. He seems to share Rusty’s opinion of Kumagai. By evoking the propaganda, Turow is essentially employing it to describe Kumagai. It might have been more courageous of him to simply have described Dr. Kumagai as buck-toothed and squint-eyed.

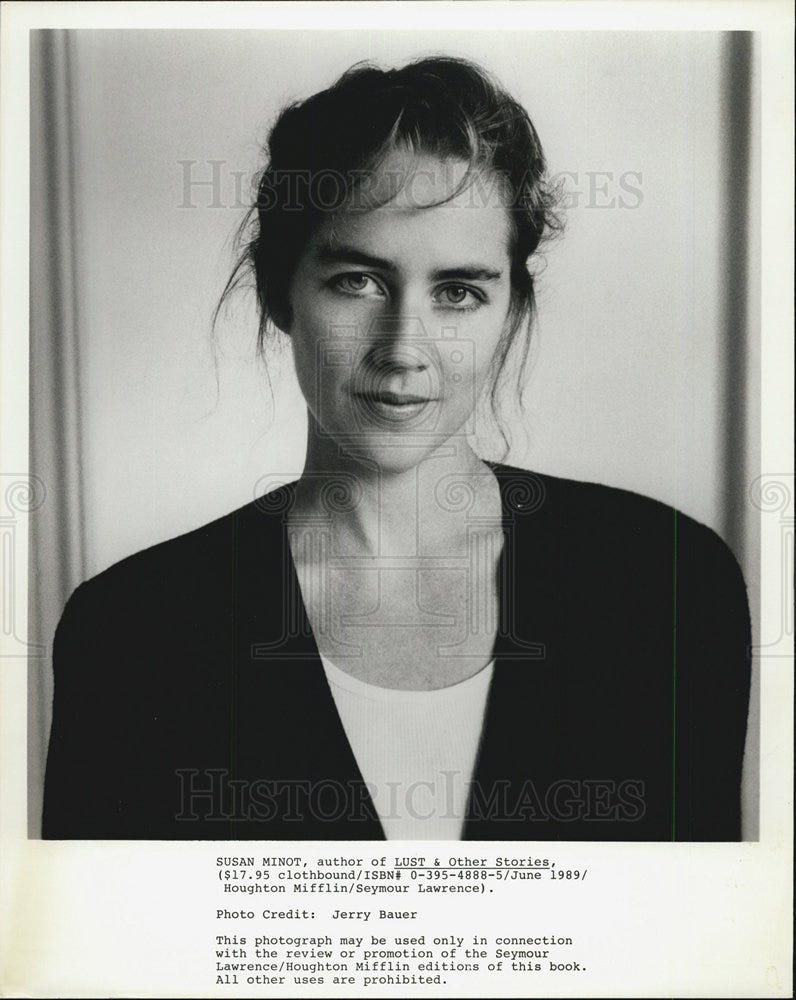

In the 1980s and 1990s, following the success of the so-called literary brat pack – Tama Janawitz, Bret Easton Ellis, David Leavitt, Jay McInerney, Lorrie Moore, Mona Simpson, Susan Minot, etc. – the east coast publishing houses went looking for the next big writer to come out of a major university’s writing program. David Guterson, Charles Frazier, Arthur Golden, Nathan Englander. All of them were, at one point or another, described as the Next Big Thing in serious American fiction. But each of these first-time authors seemed to have only one worthwhile book in him. And even those first books were drastically overhyped by their publishers and a compliant book-review complex, so that each new writer was praised as the next Bernard Malamud (Englander) or Saul Bellow (Ethan Canin) or Harper Lee (Guterson). Alas, you can generally fool the reading public once, but not twice. Thus, Guterson’s Snow Falling on Cedars was a monster hit but his follow-up novel, East of the Mountains was a disappointment. Nathan Englander’s story collection For The Relief of Unbearable Urges was successful, but none of his follow ups ever generated much interest. And some of these Next Big Writers never even managed to write a single follow up book. After writing Memoirs of Geisha, Arthur Golden was one and done. That’s not quite the case with Turow. The Burden of Proof was a brisk seller. But his subsequent books don’t seem to have done as well. At Goodreads.com, Presumed Innocent and The Burden of Proof have healthy reader approval ratings of 4.10 out of five stars and 4.06, respectively. But those are the only two Turow novels to rise above 4.0. The rest have fairly meh ratings. In backing Turow as the master of a new genre, the publishing industry seems to have bet on the wrong horse. Turow’s career has been a success, but Grisham’s career is one of the all-time best. If Turow were winning Pulitzer Prizes for his novels or having them enshrined in the Library of America, his decision to strive for literary excellence over thrills and chills might make sense. But, as far as I can tell, his work isn’t highly prized in elite literary circles any longer. Writers of Stegner’s stature no longer sing his praises. In popular fiction circles he retains a great deal of cache but nothing close to what Grisham has attained.

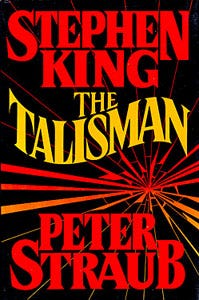

In some ways, Turow and Grisham are to the legal thriller what Peter Straub and Stephen King were/are to the horror novel. Straub tended to get much better reviews from the serious literary crowd than King did. Straub’s role model was Henry James, and he sought to write novels that were as long and complex as James’s generally were. His writing tended to be restrained and finely honed. Most of King’s best early work, on the other hand, was relatively short – Carrie, Cujo, The Dead Zone, Misery, Thinner, etc. – and fairly pulpy. He wasn’t timid about grossing out his readers or concluding his novels with big apocalyptic endings rather than subtle and ambiguous ones. Alas, Straub found himself in a sort of no man’s land. His books were generally too slow and literary to achieve massive pop fiction bestsellerdom. But they were marketed as horror novels, which tended to prevent them from being taken seriously by the smart set. His 1979 bestseller Ghost Story was essentially Straub’s Presumed Innocent, a long genre tale with literary pretensions. It sold well and got a lot of love from both critics and horror fans. But, after that, his literary ambitions seemed to turn off a lot of readers. His reached seemed to exceed his grasp. His books became longer and more complex, but not necessarily better. His so-called Blue Rose trilogy of novels ran to a total of 2,088 pages. He seemed to be swinging for the fences with every at-bat but he rarely hit more than a single. King has written his fair share of bloated misfires but, like Grisham, he is incredibly prolific and writes in a wide variety of genres and styles. Even if his literary batting average were only .500 (and it is probably much higher than that) that would still leave us with a lot of very good books.

Straub, who died in 2022, already seems to be fading from pop fiction prominence. At Goodreads, his books, with the exception of Ghost Story and those he co-authored with King, seem to garner no more than a few hundred, generally middling, reviews. Compare that with King, whose 2011 novel 11/22/63 has generated nearly fifty thousand reader reviews at Goodreads and has an overall rating of 4.34 out of five stars. Ambition is a fine quality in a writer, but it can sometimes blind him to his own weaknesses. Turow was never going to be another William Faulkner. But, had he focused more on crafting nifty plots and less on producing eye-catching phraseology, he might have become another Joseph Wambaugh, a hugely popular author of riveting institutional novels. One of his biggest mistakes was the invention of Kindle County. Though obviously based on Chicago, it is a fictionalized version of it, and those of us who don’t know the Windy City well can’t really ever be sure whether some building or cultural landmark or geographical oddity in a Turow novel is based on an actual feature of Chicago or just another of Turow’s inventions. The fact that the current David E. Kelley miniseries dispenses with the Kindle County pretense entirely and simply locates the story in Chicago indicates just what a failure Turow’s invention was. Created and expanded over the course of thirteen novels and thousands of pages, Kindle County proved completely expendable when adapting Presumed Innocent for Apple-TV. I’ve watched only the first two episodes of the series, but I can’t tell any difference between the Chicago setting of the TV show and the Kindle County setting of the novel. If Turow was trying to create a setting for his books that differed in important ways from Chicago, he seems to have failed. If was trying to create a Kindle County that was pretty much Chicago with a different name, I’m not sure why he even bothered.

For reasons that still aren’t entirely clear to me, Presumed Innocent remains, 37 years after its publication, the book generally credited with spawning the contemporary American legal thriller. But its influence seems to have been fairly limited. Most writers of legal thrillers these days seem to be aiming for Grisham-like thrills rather than Turow-like literary pretensions. In the mid-1990s, it was still possible to debate whether Turow or Grisham was the true master of the American legal thriller. But the matter is no longer up for debate. The jury has made its ruling.

I decided to never read another Scott Turow book after feeling cheated by the unreliable narrator device he used in Presumed Innocent.