THE WIT AND WISDOM OF BARNABY JONES

When people discuss the prestige TV crime dramas of the 1970s, they tend to mention Columbo, The Rockford Files, Kojak, The Streets of San Francisco, Police Story, McCloud, and McMillan and Wife. Sometimes they also throw in Starsky and Hutch, Baretta, and Angie Dickinson’s groundbreaking Police Woman. One show that doesn’t get enough attention from genre aficionados is Barnaby Jones, a Quinn Martin production that starred Buddy Ebsen and Lee Meriwether and ran on CBS TV from 1973 to 1980, for a total of 178 episodes. A Widipedia page titled “1970s American Crime Drama Television Series,” which lists its entries alphabetically, contains only four programs under the letter B: Baretta, The Blue Knight, The Bold Ones, and Bronk. Baretta was by far the most successful of this foursome, and it racked up only 82 episodes over four seasons, which is 96 fewer than Barnaby Jones’s total. The Rockford Files, one of the most highly regarded TV detective shows of all time, notched a total of 123 episodes (later augmented by 8 TV movies scattered over five years in the 1990s). Likewise, Peter Falk’s iconic Columbo character appeared in only 45 canonical episodes of that program between 1971 and 1978. After a decade-long hiatus the character was resurrected, less successfully, for an additional 24 episodes, which aired on ABC TV between 1989 and 2003. Even among Quinn Martin productions, Barnaby Jones was exceptional. The Streets of San Francisco and Cannon, both Quinn Martin productions of the 1970s, ran for a total of 121 and 122 episodes respectively.

Of course, longevity alone isn’t always a sign of a high-quality TV series. Some mediocre programs seem to last forever. And some very good programs get cancelled far too prematurely. My favorite detective series of the 1970s is Harry O, which starred David Janssen and lasted for only two seasons and a total of 44 episodes. I also liked George Peppard as Banacek (17 episodes), and was a big fan of Switch (70 episodes), which starred Robert Wagner and Eddie Albert. Crime novelist Max Allen Collins has called City of Angels, starring Wayne Rogers, “the best private eye series ever.” It debuted in February of 1976 and was cancelled in May, after a run of just 13 episodes. The fact that Barnaby Jones ran for eight seasons tells us that it was popular but not that it was necessarily a good show.

The series came along at a time when network television was focused on a 1970s version of what we nowadays call “inclusion.” These days, inclusion, when applied to television, generally refers to an effort to highlight stories featuring racial minorities, gays and lesbians, women, and others whose stories tended, in the past, to be overshadowed by the stories of heroic white, heterosexual males. In the late 1960s and the 1970s, TV networks made an effort to give their viewers heroes who weren’t necessarily ideal physical specimens (though they were all still very much white, heterosexual, and male). Thus, we got Ironside (starring Raymond Burr), a show about a San Francisco police chief who is confined to a wheelchair. We also got Longstreet (starring James Franciscus), about a blind New Orleans insurance investigator. We got Baretta (starring 5’ 4” Robert Blake) about a short detective. We got Cannon (starring William Conrad), which featured an obese private detective. And we got Barnaby Jones, which was about a senior-citizen detective. Buddy Ebsen was a few months shy of 65 when the program debuted in January of 1973. The final episode aired on April 3, 1980, one day after Ebsen’s 72nd birthday.

The series began with a crossover episode that also featured William Conrad’s Cannon character. In the opening episode, Barnaby Jones is a retired private eye. He comes out of retirement to investigate the murder of his son, Hal, who was also a private eye and a colleague of Frank Cannon’s. Together, Barnaby and Cannon bring Hal’s killer to justice. At the end of the episode, Barnaby decides that he wants to become a full-time detective again. He hires his widowed daughter-in-law, Betty (played by Lee Meriwether), to run his office.

Many of the most successful TV crime series of the 1970s employed a gimmick or two that set them apart from the rest. Columbo, for instance, had numerous such gimmicks. Foremost among these was the format. Each episode began with a murder being committed. The viewer always knew who the killer was. Columbo wasn’t a whodunit or a mystery. The pleasure came from watching Columbo develop a rapport with his chief suspect as he slowly reeled him in. What set The Rockford Files apart from other detective shows was its humor. Columbo contained plenty of humor, but it was light on violence and action, so the humor didn’t seem out of place. The Rockford Files, on the other hand, had plenty of car chases, shootouts, fistfights, and other hallmarks of the violent TV detective show. The humor in Rockford seemed more subversive than the humor in Columbo, because Rockford often employed it just as he was about to be beaten to a pulp by some thug, or as he was being led off in handcuffs by some overzealous police officer. Police Woman was distinguished by the fact that its tough-guy cop was actually a female police detective. Police Story was distinguished by the fact that it was an anthology series and featured a new set of characters with each episode. Kojak tried to distinguish itself from the pack by bringing gritty, realistic detail to its stories of crime on the streets of New York City. By comparison with these programs Barnaby Jones was fairly conventional. The writers of the show didn’t emphasize the character’s age much, and Barnaby regularly engaged in the kind of action-hero antics – car chases, shoot-outs, even karate chops – that were commonplace on TV crime dramas of the era. One thing that did distinguished Barnaby from the other detectives was his interest in forensics. His office was equipped with a laboratory where he regularly examined things – blood, dirt, fabrics, paint, etc. – under a microscope. He also had a darkroom, where he could develop his own photographs. He was ahead of the curve here. By the end of the twentieth century, forensics would be all the rage in crime dramas, not just on television but also on the big screen and in many a series of crime novels. But when Barnaby Jones debuted back in 1973, forensics generally took a back seat to shoot-outs and fisticuffs.

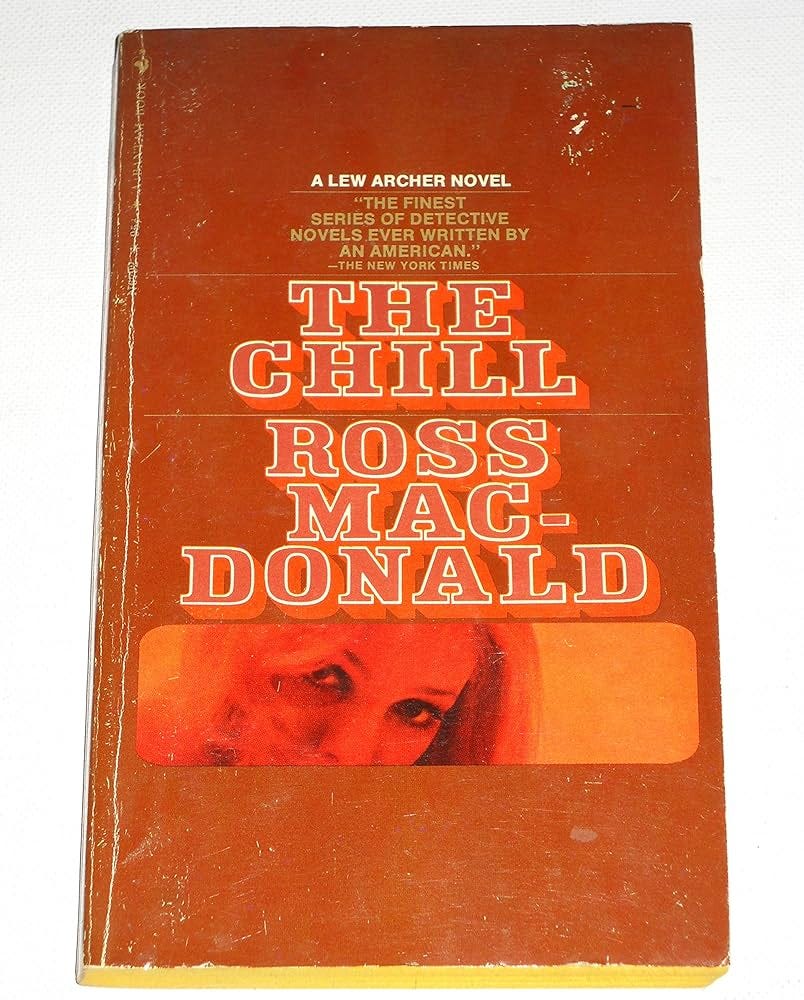

Columbo was noteworthy for the high quality of its guest stars. But many of Columbo’s most memorable guest stars also guest starred on Barnaby Jones, including Jack Cassidy, Ross Martin, Susan Clark, Roddy McDowell, Patrick O’Neal, Ida Lupino, and William Shatner. What’s more, the writers of Barnaby Jones weren’t required to employ any specific storytelling formula. Sometimes you knew from the first act who the killer was and how he did it. Sometimes these things were not revealed until the final act. Thus, when they wanted to, the writers of Barnaby Jones were free to employ the Columbo formula. Many Barnaby Jones episodes begin by showing us exactly who the killer is and how he committed the crime. Then, like Columbo, Barnaby shows up and begins slowly unraveling the villain’s perfect murder. By the time Barnaby Jones debuted, Columbo was the most highly-regarded crime show on TV, so it makes sense that Quinn Martin and company might have wanted to borrow a few pages from the Columbo playbook now and then. But Barnaby’s most obvious forebear, it seems to me, isn’t a television character at all but rather Ross MacDonald’s Lew Archer. In The Moving Target, the first Archer novel, published in 1949, we learn that the character is “approximately” 35 years old, which means that, by 1973, he would have been close to sixty, or roughly the same age as Barnaby Jones. Barnaby often comes across as a bit of a loner, but Archer is even more of a loner than Jones, since he runs a one-man detective agency. He has no office manager and relies on a messenger service to answer most of his business calls for him. But, like Jones, Archer also comes across as well educated (Barnaby used to teach college science courses) and articulate. Ross Macdonald had a Ph.D. in English from the University of Michigan, and Archer frequently finds himself engaging in literate conversations with professors and other academics. What’s more, both Barnaby Jones and Lew Archer, though they operate in southern California, tend to avoid the mean streets of Los Angeles where Philip Marlowe famously prowled. Archer is headquartered in Santa Theresa (a fictionalized version of Santa Barbara, which lies 90 miles north of L.A.), and he often finds himself roving through various small California towns in search of clues and suspects. Barnaby’s office is located in a Pasadena commercial building. Pasadena is in Los Angeles County, but Barnaby, like Archer, often finds himself wandering through hamlets and burgs that seem more like towns in the American south or Midwest than what we normally picture when we think of the Los Angeles area. Often, as in Macdonald’s books, these hamlets are given fictional names such as Bryan’s Crossing or Dalton Junction.

It is a tribute to Ebsen’s acting skills that he was able to make a success of Barnaby Jones at all. From 1962 to 1971, he starred as Jed Clampett in The Beverly Hillbillies, one of the most commercially successful TV shows of its era. Jed Clampett was a hick from Tennessee who somehow managed to make a fortune, which allowed him to move to Beverly Hills, California, where he thrived as a fish-out-of-water among his much more sophisticated and refined neighbors. Very few TV actors of the era were able to escape being typecast after portraying an iconic character in a sitcom. None of the actors in Gilligan’s Island went on to break out of their comic mold. Don Adams, Barbara Felton, and Ed Platt, who starred in Get Smart, all saw their careers peter out after the show went off the air. Things got so bad for Ed Platt that he committed suicide, in 1974, at the age of 58, having failed to resume the film career that he left in order to take on a role in a sitcom. Shrewdly, the creators of Barnaby Jones had Ebsen’s character often pretending to be just another down-home country boy like Jed Clampett. Ebsen’s Jones liked to assume an “aw shucks” manner in order to lull his prey into a false sense of intellectual superiority. Barnaby Jones claims (believably) to have been born and raised in North Carolina, and Ebsen gives the character a comfortably folksy geniality most of the time.

It must be conceded that the mysteries on Barnaby Jones are generally not all that clever or absorbing. The killers and victims tend to have very little in the way of back-story. This was true of most of the crime dramas of the era. Nowadays, my wife and I enjoy watching 1970s TV dramas in order to see the three Cs: cars, clothes, and coiffures. Barnaby himself drives a Ford LTD and the show usually features a bunch of similar early 1970s land yachts. The series began just as rising oil prices were causing Americans to turn away from massive gas-guzzlers like Barnaby’s. In a nod to this reality, his daughter-n-law, Betty, drives a cherry-red Ford Pinto (as with all other Quinn Martin productions, the cars were provided mostly by the Ford Motor Company). Julie and I enjoy it when an episode features an actual southern California street scene and we can try to identify all those bygone Mavericks and Mustangs and Thunderbirds and Pacers and Cameros and so forth as they go whizzing by. Nearly as entertaining to see are the clothes of the era. The men’s ties are often as wide as lobster bibs, and far more colorful. For a particularly egregious example of the era’s garish clothing, check out the attire worn by actor Tim O’Connor in the second episode of season two, called Death Leap. That episode also features some incredibly garish sofa upholstery. The women’s dresses frequently feature patterns that are positively psychedelic. The women’s hair is often big and bouffant-y. But even the men in your typical Barnaby Jones episode all look as if they need a haircut – including Barnaby. Their hair tends to fall down over their ears and, in the back, over the collars of their shirts or jackets. Nowadays, younger people tend to laugh when they see photos of former President Lyndon Johnson’s post-presidency hippie hair. But if you watch Barnaby Jones (or pretty much any other other 1970s American TV show) you’ll see all sorts of serious American men sporting the same shaggy appearance.

You can find, and enjoy, the three Cs on just about any 1970s detective show, but among the things that set Barnaby Jones apart from most of its competitors were the homespun pieces of wit and wisdom that Barnaby was forever spouting to his listeners. Those alone make the program worth watching. Some of these possessed the mysterious quality of a Zen koan. Some of them feel like they might have come out of Poor Richard’s Almanac. And others feel like something your grandfather might have told you when you were just young ‘un yourself. Here are just a few examples of the wit and wisdom of Barnaby Jones.

“When one egg gets broken you blame the chicken. When they’re all broken you get the feeling there has been a fox in the hen house.”

“It takes more than age to make an antique.”

“When you don’t know what you’re looking for, it doesn’t hurt to look everywhere.”

“Sometimes a man has to gamble with what he hasn’t got.”

“Even a young possum knows enough to tell when it’s been treed.”

“It doesn’t take courage to commit murder, just a particular kind of cowardice.”

“The great thing about each day is that nobody has ever used it before. It’s fresh and you can do what you want with it.”

“Never try to bury the truth. It has a sneaky way of coming back to haunt you.”

“The only thing that’s a cinch is the strap on a saddle.”

“Love is the most misused four-letter word around.”

“Bananas and grapes may come in bunches but not coincidences.”

All eight seasons of Barnaby Jones are currently available for streaming on Amazon Prime. My wife and I have been bingeing them for a month or so now. When the show debuted in 1973 I was fourteen years old and Barnaby Jones struck me as sort of a dull old fuddy-duddy. I couldn’t understand the program’s popularity. I preferred rugged tough guys like Mannix, and Rockford, and Baretta. On my most recent birthday I turned 65, roughly the same age Barnaby Jones was when the show debuted. Suddenly the character seems filled with hard-won intelligence and amazing insights into human foibles and frailties. I suspect those qualities were always there in Ebsen’s performance. They’ve just been waiting for me to grow wise enough to appreciate them. I think I’m finally there.

Honestly, I haven't seen a bad Barnaby Jones episode yet. Stumbled upon it early Season 3 now it's Season 5. J.R. has already been in a few episodes. I like that Barnaby Jones uses the forensics. He will look under the microscope 🔬 analyzing things. I turned 50 this year. Vaguely remember BJ and Hawaii Five-O 🌊 in the late 1970's. Some of the 1970's crime shows initial runs. Barnaby Jones is definitely underrated. He looks very old with his white hair and has a soft-spoken manner. It's probably why Barnaby Jones can solve so many crimes. Very intelligent and sharp mind. He has the detective skills plus the forensics ability. In most of the 1970's shows, they have a lab tech type who gives them the info they seek. Lt. Biddle also deserves more shine. He listens to BJ and backs him up when the time has arrived. Just very impressed by the show. JC

Have been watching Barnaby Jones here on ME-TV. I was surprised by the intelligent and quality episodes. Barnaby Jones similar to Columbo as he grinds down the criminal offender over time. It's 5th season episodes now where J.R. has joined the team. Barnaby, Betty, and J.R. are a formidable team. J.R. brings some energy and youth to the show. It was a smart decision to bring in J.R. to the team. Agree Barnaby Jones is underrated compared to the more notable 70's Crime Dramas. Cannon, Hawaii Five-O 🌊, Kojak, The Rockford Files, Streets Of San Francisco. It's my own fault and ignorance not watching Barnaby Jones in the syndicated episodes long ago. Guess better late than never. JC