Last November, the Atlantic published a selection of poetry called “9 Poems for a Tough Winter.” First among the nine was “So Penseroso,” a poem by Ogden Nash. I was surprised to see it because Nash, who was insanely popular from about 1931 (the year his first collection of poetry was published) until about 1971 (the year he died), has fallen seriously out of fashion over the last three or four decades. I was born in the late 1950s. My mother often quoted Ogden Nash to me. For some reason she was particularly fond of this little ditty:

THE LAMA

The one-l lama

He’s a priest.

The two-l llama

He’s a beast.

And I will bet

A silk pajama

There isn’t any

Three-l lllama.

Nash was famous for such terse little rhymes. When I mentioned his name to my regular walking partner the other day, she instantly recited one of his best-known works, a quatrain called “Reflections on Ice Breaking.” It goes like this:

Candy

Is Dandy,

But liquor

Is quicker.

Nash summed up the legendary stinginess of the Scottish with this “Genealogical Reflection”:

No McTavish

Was ever lavish.

And he summed up his opinion of one New York City borough this way:

The Bronx?

No thonx!

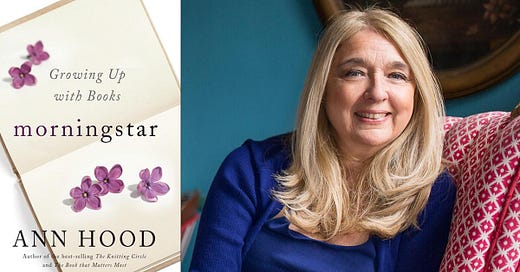

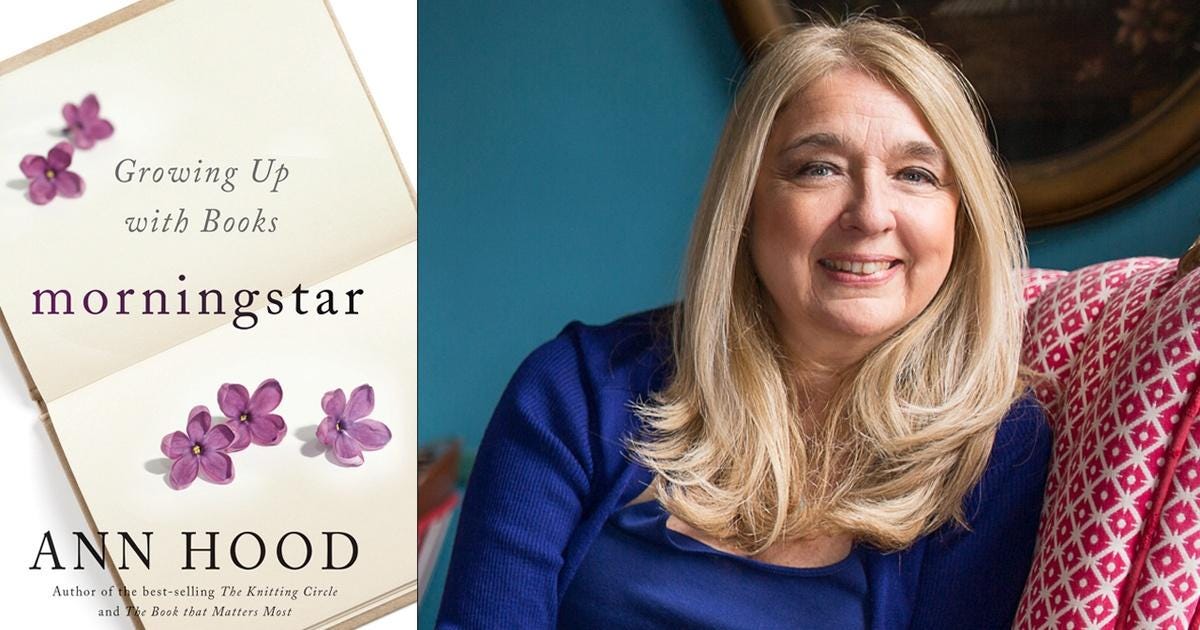

Critic Joseph Epstein spoke the truth when he said that Odgen Nash “completely dominates light verse in American literature, and no one is ever likely to surpass him.” Because he was America’s best-loved aphorist, Mark Twain often gets credited with witty maxims he didn’t actually write. Likewise, because he is about the only American ever to make a good living writing comic verse, Nash tends to get credited with all American comic verses, even those he didn’t write. In Morningstar, a lovely memoir of her reading life, novelist Ann Hood relates this anecdote about how her Aunt Angie introduced her to the world of poetry:

One afternoon, when I was seven or eight, as I sat beside her at the enamel-topped kitchen table, she produced from the depths of her handbag a neatly folded newspaper clipping. She smoothed it out and told me to read it out loud.

“’I never saw a Purple Cow,’” I read. “’I never hope to see one. But I can tell you, anyhow, I’d rather see than be one!’”

Aunt Angie hooted with laughter. “This guy, Ogden Nash, he makes the best rhymes.”

Why this poem was in the newspaper, or how Aunt Angie had heard of Ogden Nash, I cannot say. What I do know is that reading that nonsense poem out loud, feeling the rhymes slide off my tongue, reaching the delightful ending – “I’d rather see than be one!” – was an experience that I still can’t describe, like the first time you ride your bike without training wheels or watch television in color instead of black and white. A world opened up.

There’s only one thing wrong with Hood’s charming anecdote. The poem she quotes was first published in 1895, six years before Nash’s birth, and was written by the long-forgotten Gelett Burgess (above). I’ve no doubt that the scene played out exactly as Hood described it. By 1963, the year Ann Hood turned seven (and I turned five), Nash was so popular that nearly every short comic American poem tended to get credited to him by harried newspaper columnists who didn’t have time to look up the origins of every poem they quoted.

Alas, Nash’s name is no longer a household name all across America. I’m a long-time fan of Nash’s work. I’ve also collected some of his autographed books and his signed personal correspondence. But even I long ago learned to accept that my poetic hero is gradually fading from the American cultural memory. There appear to be very few people younger than I am (62) who even know who he was, and fewer still who are capable of reciting his verse from memory.

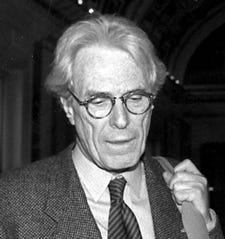

In 2012, I attended the Sewanee Writers Conference in Sewanee, Tennessee, where I worked with a variety of very talented poets, including Mark Strand (above), who was the U.S. Poet Laureate for 1990-91. All of us out-of-town participants in the workshop flew to Nashville before boarding a bus that took us to Sewanee. In Nashville, I mentioned to Strand that the city was named for a General in the Continental Army who had a much more famous relative, an American poet. “Not Ogden Nash?” he said. “The very same,” I responded. Strand’s poetry is famously surreal and often difficult to decipher. I doubted that he’d be much interested in a popular and accessible poet like Nash, but I was wrong. Although Strand rarely employed rhyme or meter in his work, he said he believed every poet should start out writing in those forms. “How can you rebel against convention,” he asked the free verse poets in one of my classes, “if you don’t know what the conventions are?” Not only was Strand fond of Nash, he told me that at his age (he was 78 at the time) he mostly enjoyed reading in various traditional genres, particularly mystery novels. At the end of the workshop, he wrote down his Brooklyn home address in my notebook and encouraged me to write to him. I wrote him only once, and he promptly sent me a lovely handwritten reply dated August 23, 2012. I didn’t know it at the time, but he was suffering from cancer during the summer of 2012 and would die just two years later. Alas, Strand was about the only Nash fan I met at Sewanee. Most of the younger poets I mentioned him to had no idea who Ogden Nash was.

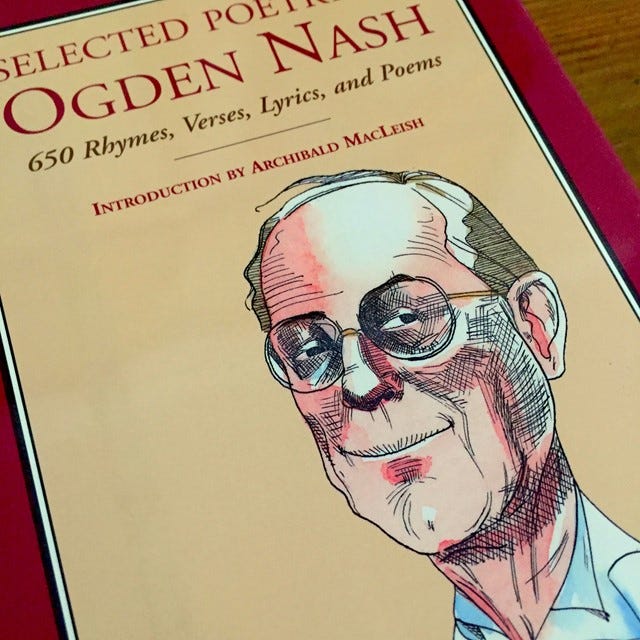

Strand and Nash had little in common as writers, but as readers they shared a fondness for crime fiction. Although Ogden Nash never wrote any prose fiction, to my knowledge, many of his poems are essentially crime stories in verse. I have more than a dozen volumes of Nash’s work around the house, but the most convenient source is a tome called Selected Poetry of Ogden Nash: 650 Rhymes, Verses, Lyrics, and Poems, published by Black Dog & Leventhal Press in 1995 and featuring an introduction by Archibald MacLeish. The very first poem in this massive collection is titled “The Strange Case of the Lovelorn Letter Writer,” and it retells the story of one of English literature’s most famous suicides, although the identity of the lovelorn letter writer remains a mystery until the poem’s final word.

A few pages later we find a poem called “The Strange Case of Mr. Ormantude’s Bride,” which tells the tale of a murder by poisoning. Next comes “The Solitude of Mr. Powers,” about a husband who simply walks away from his marriage one day for a very mysterious reason. Another spouse mysteriously disappears in “The Mind of Professor Primrose.” On page 28 we find “The Strange Case of the Dead Divorcee.” In that comic masterpiece two women are murdered by husbands wielding ice picks. On page 46 we find “A Warning to Wives,” which begins with a quote from a news story in the Boston Globe: “The outcome of the trial is another warning that if you must kill someone, you should spare the person possessing life insurance…Figures are available to show that convictions are much more common in ‘insurance murders’ than in any other types of homicides.” Nash’s poem, addressed to unhappy wives, advises them of various ways of bumping off a husband, but each piece of advice comes with a warning to call off the plan if the intended victim possesses life insurance. Nash’s poem titled “Love Under the Republicans (or Democrats)” tells us that no matter what the political situation of the country, love often leads to its opposite. The poem ends with this quatrain:

And every Sunday we’ll have a lark

And take a walk in Central Park.

And one of these days not too remote

I’ll probably up and cut your throat.

Likewise, the poem “Lucy Lake,” a spoof of William Wordsworth’s so-called “Lucy poems,” sings the praises of the ever-optimistic title character, but comes to this startling conclusion:

A visit to Lucy’s bucks you up,

Helps you swallow the bitterest cup.

Lucy Lake is meek as a mouse.

Let’s go over to Lucy’s house,

And let’s lynch Lucy!

Elsewhere in the collection we find “The Strange Case of Mr. Donnybrook’s Boredom,” which culminates in an act of mariticide (the killing of a husband). But unlike the wife in James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity, who murdered her husband for the insurance money (apparently she hadn’t read “A Warning to Wives”), Mrs. Donnybrook kills her husband for a reason that is found nowhere else in crime literature. (Speaking of James M. Cain, Nash once wrote a poem called “Why the Postman Has to Ring Twice,” but it is a lament for the death of the telegram and not a hardboiled crime tale.)

References to mystery fiction abound in Nash’s work. The poem “Polterguest, My Polterguest,” which describes the behavior of an atrocious houseguest named Hecate Hopper, concludes with these two quatrains:

Hecate Hopper the Polterguest

Left stuff to be posted or expressed,

And absconded, her suavity undiminished,

With a mystery story I hadn’t finished.

If I pushed Miss Hopper under the train

I’d probably have to do it again,

For the time that I pushed her off the boat

I regretfully found Miss Hopper could float.

Perhaps Nash’s most direct engagement with mystery fiction occurs in a poem called “Just Holmes and Me and Mnemosyne Makes Three.” In it, Nash confesses to having a terrible memory but takes comfort from the fact that the great Sherlock Holmes (or, more accurately, his creator Arthur Conan Doyle) had a poor memory also. The poem concludes this way:

Me, I can never be elected to any office, because I am nearsighted

and frequently forget the face of an acquaintance, and, worse,

I invariably forget the name,

So I am solaced by the discovery that my lifelong hero Mr. Sherlock

Holmes was once the same.

In “The Adventure of the Speckled Band” (The Complete Sherlock

Holmes, Doubleday, 1953), the proposed victim of a fiendish

plot introduces herself on page 294 as Miss Helen Stoner,

stepdaughter of Dr. Grimesby Roylott, of Stoke Moran,

An unpleasant man,

Yet on page 299 Holmes says to her, “Miss Roylott…you are

screening your stepfather,” a slip that Miss Stoner left

uncorrected, either through tact or because her mind was

upon her approaching wedding,

For she had recently become betrothed to Mr. Percy Armitrage,

second son of Mr. Armitrage, of Crane Water, near Reading.

Well, whatever caused Holmes’s error and Miss Stoner’s overlooking

it, I have this reflection to cheer me as I step from the mounting

block to the saddle of my high-wheeled bike:

Great minds forget alike.

Murder and mayhem and violent death can be found throughout the poetic works of Ogden Nash. In one poem he tells us:

Some people suffer weeks of remorse after having committed the slightest peccadillo,

And other people feel perfectly all right after feeding their husbands arsenic or smothering their grandmother with a pillow.

And then he concludes:

There is only one way to achieve happiness on this terrestrial ball,

And that is to either have a clear conscience, or none at all.

In “Mr. Barcalow’s Breakdown” we hear of a grandmother scalded to death in a shower, and a seventeen-year-old boy who burns down a schoolhouse and kills a music teacher and a janitor.

Nash was a man who was addicted to both alcohol and gambling, and his poems often take place among the type of people who populate the world of Damon Runyon: horse-race gamblers, card players, saloon habitués, roués, and women of questionable repute. Thus, even when there is no actual criminality in a poem, it often feels crime-fiction-adjacent. Of course, he was also a bit of a prude, even by the standards of his fairly prudish generation, so, although it is often suggested, there is rarely any outright obscenity or depravity in his work. This is curious, because his work often criticizes prudery. In fact, one of his crime poems is called “The Strange Case of the Irksome Prude.” It is the story of a pickpocket named Harold Scrutiny and his nemesis Detective Guilfoyle. The final line reads: “Don’t be a prude.”

If you find yourself in possession of a large volume of Nash’s poetry and are eager to seek out just the crime-fiction-adjacent poems, my advice is to look through the index for entries beginning with the words “The Strange Case of.” Nash wrote a lot of them and they usually involve some sort of violent death. In “The Strange Case of Mr. O’Banion’s Come-Uppance,” a tiresomely cynical scoutmaster meets a frightful but appropriate demise. Boy Scouts also figure in “The Strange Case of Mr. Wood’s Frustration.” Alas, the poem is lame and concludes with one of Nash’s dumbest puns. “The Strange Case of the Cautious Motorist” concludes with another violent, and ironic, death. Another motorist meets a curious fate in “The Strange Case of Mr. Niobob’s Transmogrification,” a tale reminiscent of Steven Spielberg’s debut film Duel, based on a short story by Richard Matheson. No violence is found in “The Strange Case of Mr. Pauncefoot’s Broad Mind,” but the title character does solve a vexing problem cleverly by the close of the poem. “The Strange Case of Mr. Ballantine’s Valentine” includes both murder and another act of violence, but, as the title suggests, concludes with love. In “The Strange Case of the Lucrative Compromise,” a young man with prodigious gifts as both a healer and a wordsmith, finds an inventive way to put both skills to work. And “The Strange Case of the Ambitious Caddy” ends with the suggestion that the title character just might be murdered the next day by…Ogden Nash himself! My favorite of these is “The Strange Case of Mr. Palliser’s Palate,” in which the French language isn’t the only thing that gets murdered.

Nash was also extremely fond of children, and wrote quite a bit of verse for them, including a well-known children’s storybook called The Tale of Custard the Dragon. Some of his observations about childhood are sentimental and others are more gimlet-eyed. But even in his poetry for children, mayhem and malice are rampant, particularly when animals are involved. In one poem a lion eats a Mr. Bryan while the lion’s lioness eats Bryan’s Bryaness. In another poem a giant python swallows a scientist, thus allowing said scientist to confirm, before dying, that the python does indeed possess 318 pairs of ribs. Of another voiceless predator Nash writes, “This I know about the shark/His bite is worser than his bark.” And he warns visitors to South American jungles, “If called by a panther/Don’t anther.”

Nash was once the most popular and best-loved poet in America. Today he is largely unknown by most people under 60. This is a shame. Resurrecting Nash might be difficult in these politically-correct times, because much of his humor comes from old-fashioned notions about marriage, the roles of men and women in society, and the innate characteristics of various nationalities (i.e., the stinginess of Scots). At first glance, “The Japanese” would appear to be a problematic poem:

How courteous is the Japanese;

He always says, “Excuse it, please.”

He climbs into his neighbor’s garden,

And smiles, and says, “I beg your pardon”;

He bows and grins a friendly grin,

And calls his hungry family in;

He grins, and bows a friendly bow;

“So sorry, this my garden now.”

But Nash wasn’t talking about race in the poem. Rather he was criticizing the rampant colonization of Asia that the Japanese military undertook in the first four decades of the twentieth century. During that period Japan sent occupying forces into Manchuria, Korea, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, and many other parts of Asia. A young contemporary reader seeing the title of the poem and the Pidgin English employed by Nash might accuse him of political incorrectness (or worse). But nowadays, “colonialism” is one of the evils most reviled by woke social-justice warriors. The fact that Nash was decrying colonialism nearly 90 years ago ought to earn him some respect from the woke crowd. But in an age where people are quick to take offense over the slightest thing, a jokester like Nash, who poked fun of virtually everything he wrote about, isn’t likely to be welcome.

Ah well, if you like murder, mayhem, and mystery, you ought to take a look at Ogden Nash’s poetry. It’s nearly as bloody as the collected works of Mickey Spillane. And it’s a helluva lot funnier.

I can still recite the one that tickled me as a young girl! Hopefully my brain didn’t mangle it over the years.

“Tell me, oh octopus, I begs,

Is those things arms, or is they legs?

I wonder at thee, oh octopus

If I were thou, I’d call me us!”

Thanks Kevin. Well, since I am from the Bronx I will say "Thonxs"