Few great authors actually hit the ground running. Most of them stumble and fall a bit before finding their stride. John Steinbeck’s first novel, Cup of Gold (1929), is probably his worst. Ernest Hemingway’s first novel, The Torrents of Spring (1926), is a pallid spoof of a now-forgotten Sherwood Anderson novel. Sinclair Lewis’s first five novels – Our Mr. Wrenn, The Trail of the Hawk, The Job, The Innocents, and Free Air – are all eminently forgettable. Steinbeck, Hemingway, and Lewis would all go on to win Nobel Prizes, but their first novels were anything but auspicious. This is the general rule in American fiction, but there have been some notable exceptions.

In 1971, at the age of 34, Joseph Wambaugh, still an officer with the Los Angeles Police Department, published his first novel, The New Centurions. It followed the fortunes (and misfortunes) of three LAPD rookie cops, all of whom joined the force together in 1960, the same year that Wambaugh did. The book was published in January, and by February 7 it was the tenth bestselling work of fiction in the country. By March 28, it had jumped to the third spot, surpassing Erich Segal’s Love Story, which had dominated the list for 57 consecutive weeks. Not until October 3 – eight months after making its debut on the list – did Wambaugh’s novel finally fall out of the top ten.

But The New Centurions was more than just a commercial blockbuster; it was also an important piece of American literature. And it remains as relevant today as it ever was. It is a story of police brutality, racism, public unrest, systemic rot, poverty, and the seemingly everlasting tension between police departments and the communities they are supposed to protect and serve. Ernest Hemingway once asserted that, “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.” You could just as truthfully assert that all modern cop literature comes from one book by Joseph Wambaugh called The New Centurions. In fact, plenty of knowledgeable people have made that claim, including Michael Connelly, creator of the Harry Bosch novels, who wrote, “Joseph Wambaugh is the master of the modern police novel – no, scratch that, he invented the modern police novel.” This isn’t to say that nobody ever wrote about cops before Wambaugh did. That, obviously, isn’t true. But prior to Wambaugh’s arrival on the literary scene, most cop books were novels of mystery and detection. Wambaugh’s early books (and many of the later ones, as well) were about the daily working lives of patrol officers. The books didn’t set up and then resolve mysteries. They basically followed LAPD officers on their daily rounds in order to illustrate what police work was really like. This wasn’t Dragnet or Columbo. This was a report from a writer who had done the job himself.

The New Centurions was unlike any crime novel published before it. Wambaugh’s mean streets were nothing like Raymond Chandler’s. Random acts of senseless violence rarely occurred in the novels of Chandler and his ilk. The criminals in classic crime novels generally have motives and make plans and think everything out in advance. What’s more, the crime fighters in those books generally solve every case. Wambaugh’s cops are faced with a starker reality. They are patrolmen. They don’t investigate murders. They take radio calls that send them off to referee domestic disturbances, street fights, bar fights, landlord/tenant disputes, and other types of disorder. They get called to the scene of plenty of thefts and robberies, and even a few murders, but they don’t solve these crimes. They take reports. They advise the victim (or his survivors) that that he may never get any restitution. They lock down the scene until the detectives arrive, and then they move on to answer the next radio call.

Early on in The New Centurions, a veteran LAPD officer tells a trainee, “You’re going to find out before too long that we’re the only ones that see the victims. The judges and probation officers and social workers and everybody else think mainly about the suspect and how they can help him stop whatever he specializes in doing to his victims, but you and me are the only ones who see what he does to his victims – right after its done.” And often, what they see is horrible. Re-reading it recently, I had to skip to the end of a scene that involved both child- and animal-abuse.

Wambaugh begins his book in August of 1960, when his three protagonists are still just cops-in-training. He checks in with them every August through 1965. Anyone familiar with California history will know that the infamous Watts Riots (now sometimes referred to as an uprising or rebellion) took place in August of 1965. Many Americans, particularly middle-class whites, were taken by surprise by the riots, and Wambaugh’s entire project seems to have been to demonstrate that this tragedy didn’t arise suddenly or unexpectedly. Relations between the LAPD and the “Negro” community of Los Angeles had been tense for a long time. As rookies, all three of Wambaugh’s protagonists are assigned to districts of L.A. populated mainly by impoverished minority members. They get an up-close look at just what a powder keg certain parts of the city are. The book is so eerie in the way that it foreshadows the protests/riots that followed the killing of George Floyd that I’m surprised that few if any cultural critics have referred to it in recent years. But that is probably just as well. If the kind of censors that have recently been bowdlerizing books by Roald Dahl and Ian Fleming and Agatha Christie ever took a whack at censoring Wambaugh’s early work, they would likely leave no sentence unaltered. It is filled with the kind of racist language that was no doubt part and parcel of nearly every LAPD officer’s vocabulary back in the 1960s. Here’s a sample.

“I gotta transfer out of University,” said Rantlee.

“Why?”

“Niggers are driving me crazy. Sometimes I think I’ll kill one someday when he does what that bastard in the tow truck did. If someone would’ve made the first move those savages would’ve cut off our heads and shrunk them. Before I came on this job I wouldn’t even use the word nigger. It embarrassed me. Now it’s the most used word in my vocabulary. It says everything I feel…I’m finding myself agreeing with every right wing son of a bitch I ever read about. I wasn’t brought up that way. My father’s a flaming liberal and we’re getting so we hate to see each other anymore because a big argument starts.”

Wambaugh seems especially sympathetic towards the LAPD’s black cops, who were an extreme minority back then and who play only small roles in his book. Lots of racist banter takes place every morning at roll call when the supervisor reads a summary of all the major crimes that took place on the previous watch. At one point, Wambaugh writes, “Gus glanced over at the two Negro officers who sat together near the front, but they laughed when the others did and showed no sign of discomfort. Gus knew that all the ‘down heres’ referred to the Negro divisions and he wondered if all the cracks about the crimes affected them personally. He decided they must be used to it.” Often the black cops in Wambaugh’s books seem forced to decide whether they are African-Americans or cops, because the culture of the LAPD doesn’t allow them to be proud members of both tribes. Undoubtedly that still goes on in police departments across the U.S., which may explain why the Memphis cops who allegedly killed Tyre Nichols were all black.

Even some of Wambaugh’s racist white cops decry the treatment of their black colleagues:

“I just talked to old Sam Tucker,” said Whitey with a deep sigh. “The old bastard gets lonesome there at the desk. We was academy classmates, you know. Twenty-six years this October. It’s tough on him being colored and working a nigger division like this. Some nights he feels pretty low when they bring in some black bastard that killed an old lady or some other shitty thing like that, and these policemen shoot off their mouth in the coffee room about niggers and such. Sam hears it and it bothers him, so he gets feeling low.”

Race and racism infuse nearly every page of the novel. Any attempt to try to clean it up would simply weaken Wambaugh’s whole point, which is that what happened in August of 1965 should have been predictable to anyone who had spent any time inside the LAPD back in the early 1960s.

In 1972 The New Centurions was made into a film starring George C. Scott and Stacy Keach. The book also became a bestseller in paperback. But the cultural impact of Centurions was larger than its official footprint. Although he got no money or credit for it, Wambaugh and his book were clearly the inspiration for the ABC TV series The Rookies, which debuted in 1972. Even today, more than a half century later, Wikipedia’s entry for The Rookies notes that, “The success of Joseph Wambaugh’s book, The New Centurions…had sparked interest at the time in a more realistic depiction and storytelling of the typical uniformed officer.” Before Wambaugh burst on the scene, most TV crime shows were closer in spirit to the drawing-room mysteries of Agatha Christie than to the kind of gritty, realistic tales that have dominated TV ratings and bestseller lists for much of the last half century. Hill Street Blues, Homicide: Life on the Street, NYPD Blue, The Wire – all of these and many others owe a huge debt to the works of Joseph Wambaugh in general and Centurions in particular. Even today, the debt keeps adding up. The current ABC TV series The Rookie, starring Nathan Fillion, is basically just an updated version of The New Centurions, though, naturally, Wambaugh gets no official credit for it. That series has since birthed a spinoff, The Rookie: Feds, which applies the Centurions format to a group of newbie FBI agents. Many of these bastard offspring of Centurions are very good. The Rookie, in particular, does an admirable job of highlighting the racism and sexism and brutality that still occasionally mar the operations of the LAPD. But none of these intellectual properties has yet surpassed the grittiness or authenticity of Wambaugh’s original. Even if it had been the only book he ever published, The New Centurions would have cemented Wambaugh a permanent place in American cultural history. But he was just getting started.

Thirteen months after the publication of Centurions, Wambaugh returned with The Blue Knight. Published in February of 1972 and set in 1971, it covers just three days in the life of Los Angeles Police Department Officer William “Bumper” Morgan. Born in 1921, Morgan joined the force in 1951, after an eight-year career in the military. He is now just 72 hours away from completing his twenty years of service on the LAPD. After that, he can retire and collect a pension equal to forty percent of his monthly pay, every month for the rest of his life. He plans to leave L.A., marry his college professor girlfriend, Cassie, and move to San Francisco, where a cushy job awaits him as head of security for a large and profitable corporation. But getting through those last three days will not be easy. Bumper is a reckless tough guy who loves butting heads with real criminals.

By March 19 The Blue Knight was on the New York Times bestseller list, in tenth place. Wambaugh’s book debuted on the list just one week after George V. Higgins’s novel The Friends of Eddie Coyle had arrived on it. Higgins was a lawyer who had spent years working as a government prosecutor, and he specialized in organized crime cases. He was able to bring to his novel the same first-hand knowledge of crime and criminals that Wambaugh brought to The Blue Knight. The Friends of Eddie Coyle is widely considered one of the best American crime novels of all time. Elmore Leonard and Dennis Lahane are just two of the highly regarded crime writers who claim to have been heavily influenced by it. As good as it is, however, it is the only one of Higgins’s twenty-seven novels that ever achieved blockbuster status. Curiously, The Blue Knight and Eddie Coyle seemed to have been handcuffed to each other during their stay on the bestseller list (which was appropriate, since The Blue Knight is a cop and Eddie Coyle is a criminal). They were almost never far apart. Most weeks they occupied adjacent spots on the list. They both dropped from the list at about the same time that Eudora Welty’s novel The Optimist’s Daughter arrived on it. Welty was one of the best American short story writers of the twentieth century but she was not a natural novelist. The Optimist’s Daughter would eventually beat out all the other novels of 1972 for the Pulitzer Prize in fiction, but even back then it looked more like Welty was being given a make-up award, a prize honoring her previous achievements rather than the book in question. The Friends of Eddie Coyle was almost certainly the best American novel published in 1972 and The Blue Knight was nearly its equal. But the staid academics of the Pulitzer committee likely never even deigned to consider either book, seeing as how Higgins and Wambaugh were mere crime writers.

Like its predecessor, The Blue Knight was quickly snatched up by Hollywood. In 1973 it was dramatized as a four-part TV miniseries that was broadcast over consecutive evenings in prime time. William Holden, who played Bumper Morgan, earned an Emmy Award for his performance. In December of 2022, film director Whit Stillman (The Last Days of Disco) noted on Twitter, “If memory serves, the Joseph Wambaugh mini-series, The Blue Knight, was perhaps the beginning of Quality TV.” The miniseries was re-cut and released in Europe as a theatrical film. In a 2012 reassessment of the film, a reviewer for Time Out magazine called it “seminal stuff” and noted that the TV series had had a “tentacular influence over subsequent developments in US police representation…” The mini-series was spun-off into a regular dramatic series, which starred George Kennedy and aired on CBS for twenty-three episodes in 1975 and 1976. Again, the influence of Wambaugh’s book would expand far beyond its official spin-offs. Bumper Morgan’s DNA can be found all over the various crusty old beat cops who showed up as regulars on dozens of police shows over the next few decades, always representing the good old days of retail police work and griping about the younger cops and their reliance on computers and forensics.

Wambaugh’s third book, The Onion Field, was a departure for him, a nonfiction work about the notorious kidnapping, in March of 1963, of two LAPD plainclothes officers, one of whom was also murdered. Truman Capote, who had practically invented the modern true-crime blockbuster with his 1966 book In Cold Blood, praised Wambaugh’s book, calling it, “a distinguished contribution toward the gradually enlarging field of the ‘factual novel.’ A fascinating account of a double tragedy: one physical, the other psychological.” Reviewing the book for The New York Times, James Conaway wrote: “Wambaugh is obviously indebted to Truman Capote — who, in 1965, demonstrated his skill in applying a novelist's techniques to a true crime narrative. Both In Cold Blood and The Onion Field involved a prodigious amount of research, and are equally compelling. Wambaugh takes greater liberties with his characters and he lacks Capote's neatness. But in terms of scope, revealed depth of character, and dramatic coherence, this is the more ambitious book.” The book spent fourteen weeks on the New York Times non-fiction bestsellers list in late 1973 and early 1974, rising as high the fourth spot.

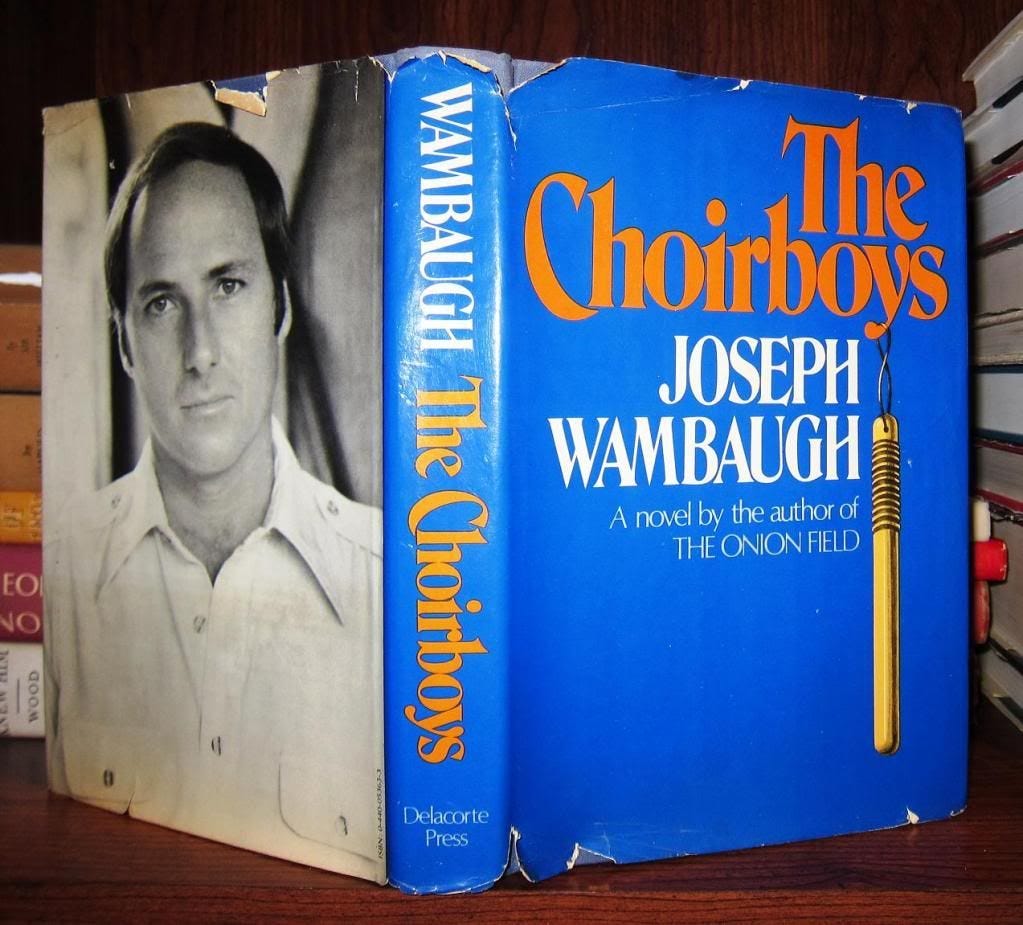

In 1975, Wambaugh published his third novel (and fourth book), The Choirboys, which many people consider his masterpiece. Up until that time, Wambaugh had written primarily in a realistic mode. His books were often very critical of the LAPD and didn’t shy away from the racism, homophobia, and brutality endemic to the department, but they were also pretty straightforward accounts of life as an L.A. cop. And they didn’t preclude the possibility that some LAPD officers were actually pretty decent human beings. Virtually none of the cops in The Choirboys is a decent human being. To varying degrees, they are corrupt, dishonest, violent, racist, homophobic, sexist, and brutal. It isn’t a coincidence that Wambaugh retired from the LAPD a year before the publication of The Choirboys. It’s unlikely he could have published The Choirboys and remained in good standing with his superiors.

But Wambaugh’s retirement wasn’t motivated entirely by a desire to write more freely about the LAPD. In 1973, NBC debuted a new anthology TV series called Police Story. It was created by Wambaugh and became a hit, running for a total of six seasons and 98 episodes. This series, and Wambaugh’s many promotional appearances on The Tonight Show and other TV chat programs, made the ex-cop pretty much a household name in America. Suddenly, people began calling up the LAPD and asking if Joseph Wambaugh could personally come out and investigate the matter of their stolen bicycle or their noisy neighbor or their smashed car window. Aspiring scriptwriters would show up at Wambaugh’s station house and drop off scripts they hoped he would consider for use on Police Story. Others brought in fat crime novels, in manuscript, and dropped them off at the front desk, with a note addressed to Wambaugh. Criminals that Wambaugh arrested on the street would ask for his autograph. Even fellow cops began rushing to open doors for him or fetch him coffee. By 1974, Wambaugh realized that his celebrity had made it impossible to do his job as a cop. Reluctantly he resigned. (Wambaugh wasn’t the first member of the LAPD to give up police work for the entertainment world; Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry spent seven and a half years with the LAPD before leaving to focus fulltime on a career as a TV writer and producer. The character of Mr. Spock was reputedly based on former LAPD Chief William H. Parker, under whom both Roddenberry and Wambaugh served.)

Published in late 1975, The Choirboys debuted on the New York Times Bestsellers list on November 30. Despite its late start, the book would go on to be the fifth bestselling novel of 1975. By January 18, 1976, the book had reached third place on the New York Times’s list, behind only E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime and Agatha Christie’s Curtain (she had died six days earlier). By February 8, only Agatha Christie was outselling Wambaugh, making him the bestselling living author in America, surpassed only by Christie’s ghost.

By late 1975, Wambaugh had produced four of the decade’s best books, and yet he remained largely ignored by the serious literary crowd. John Leonard, as editor of the New York Times Book Review, was a high-ranking member of that crowd, and the fact that he chose to review The Choirboys himself, suggests that he, at least, had some notion of just what a cultural juggernaut Wambaugh had become. Alas, Leonard’s reviews were often marred by his heavy-handed attempts to impress others with his wit and style, which were rather weak instruments. He said of The Choirboys, “It’s as though Catch-22 had been written by Popeye Doyle.” Presumably this was meant as high praise, but why drag a fictional cop (based on actual NYPD officer Eddie Egan) into the mix in order to praise an actual cop? Why not simply state that (now former) LAPD officer Joseph Wambaugh has written a black comedy every bit the equal of Catch-22? Leonard goes on to say, “Very little in Wambaugh’s first two novels prepares one for the scabrous humor and ferocity of The Choirboys.” That sounds good, but then he has to ruin it with another attempt at humor: “The New Centurions (1971) and The Blue Knight (1972) were bittersweet slices of naturalism, Hamlets on wry crisp, as if to elaborate the extenuating circumstance that cops, too, have feelings and may often be the victims of their particularity. In The Choirboys Wambaugh comes on like Celine derailed along the laugh-track. His characters are a brutalized M*A*S*H unit. Their giggle is a kind of howling, most of which can’t be quoted in a family newspaper…Having recently retired from the LAPD, Wambaugh seems to be waving goodbye to all his liberal pieties. Each of his choirboys…wears his cynicism like a bulletproof jockstrap.” It’s difficult to make much sense of this word salad (“Their giggle is a kind of howling”?). Leonard seems to be laboring to make a play on the phrase ham-on-rye but there is very little Hamlet-like about Wambaugh’s cops. Rather than being crippled by indecision, they seem easily able to make one bad decision after another. Yeats could have been writing about Wambaugh’s choirboys when he noted that “the worst are full of passionate intensity.” As for “Celine derailed along the laugh-track,” well, you’re on your own with that one. I’m much more familiar with the M*A*S*H franchise than I am with the works of Celine, and here Leonard seems to be on firmer ground. What The Choirboys did for American big-city police departments is comparable to what Robert Altman’s 1970 film M*A*S*H did for the American military: expose the incompetence, stupidity, and brutality that marred their often noble missions.

At any rate, the fact that an intellectual snob like Leonard wanted it known that he had read all three of Wambaugh’s novels is telling. By the mid-70s Wambaugh occupied an interesting position in American letters – too dark and disturbing to be fully embraced by the mystery establishment, but too much of genre writer to be fully embraced by the literary elite. In 1970, the Mystery Writers of America awarded its Best Novel prize to Dick Francis’s Forfeit. Over the next decade, Wambaugh would completely alter the American crime-writing landscape. These days, crime-writing giants like Michael Connelly and James Ellroy readily acknowledge the debt they owe to Wambaugh. But it took a long time for his influence to really take hold. In 1981, by which time Wambaugh had published five novels (six, if you count The Onion Field), The MWA awarded the Edgar for Best Novel to…Dick Francis’s Whip Hand. At some point in his career, Wambaugh should probably have been recognized with a Pulitzer Prize for his work, and yet he had trouble gaining recognition even from the MWA. To this day, not only have none of his sixteen novels been honored with an Edgar Award, not one has ever even been nominated for the prize! The MWA has twice awarded Wambaugh a nonfiction Edgar (for The Onion Field, in 1974, and Fire Lover, in 2003), and once awarded him an Edgar for Best Motion Picture Screenplay (for The Black Marble, in 1981). In 2004, he received the MWA’s highest honor, the Grand Master Award. But the fact that his novels have garnered no awards, either from mainstream-literary bodies or mystery-fiction guilds, indicates just how difficult his accomplishments are to place in American literature, and how underappreciated they are.

Back in the 1970s, I credited the greatness of Wambaugh’s books to the fact that the author had actual experience as a police officer. I assumed that, as more police officers took up writing fiction, we would come into a golden age of gritty police procedurals. It never really happened. Nowadays, bookstore shelves groan under the weight of novels written by cops or ex-cops.

But none of those writers has come close to accomplishing what Wambaugh did in just his first five years as a professional (but part-time) writer. Here’s editor and publisher Otto Penzler, founder of the Mysterious Press, writing in The New York Sun:

“American police writers must pay obeisance to Joseph Wambaugh, who showed what it was really like to spend your life in a uniform. James Ellroy credits the former cop with giving him direction, and there can be little doubt Wambaugh also influenced such superstars as Michael Connelly (whose Harry Bosch is in the pantheon of all-time great detectives), John Sanford (whose Lucas Davenport regularly and deservedly makes the best-seller list), and James Patterson (whose Alex Cross series are among the best-selling books of all time).”

In an influential 1989 essay for Harper’s called Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast, Tom Wolfe noted that, at some point in the mid-twentieth century, serious American literary novelists stopped paying much attention to life as it is actually lived by most ordinary Americans (whom he dubs the “billion-footed beast”) and began playing postmodern games in the manner of John Barth’s Chimera and Ronald Sukenick’s Up. He quotes John Hawkes, another postmodernist, who once wrote that, “I began to write fiction on the assumption that the true enemies of the novel were plot, character, setting, and theme.” Wolfe disliked this trend. He believed highbrow literary types had ceded the field of realistic fiction to writers of more commercial fiction. He wrote:

In many years, the most highly praised books of fiction have been overshadowed in literary terms by writers whom literary people customarily dismiss as “writers of popular fiction” (a curious epithet) or as genre novelists. I am thinking of novelists such as John le Carré and Joseph Wambaugh. Leaving the question of talent aside, le Carré and Wambaugh have one enormous advantage over their more literary confreres. They are not only willing to wrestle the beast; they actually love the battle.

If you are not old enough to have been an avid cultural consumer back in the 1970s it is probably difficult for you to appreciate the way that profanity was used back then. Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H, released in 1970, was the first mainstream American film to feature the use of the word “fuck.” Carnal Knowledge, released one year later, was the first mainstream film to employ the word “cunt.” Blazing Saddles, released in 1974, was the first American film to feature audible farting. The “n” word is used numerous times in Blazing Saddles, always for comic effect. Throughout most of American history, words like fuck and cunt and even fart couldn’t be used in popular literature or cinema or really any other venue. But in the 1950s and 1960s, British and American publishers went to war with the government censors who had made it impossible to legally publish books such as D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, and William S. Burrough’s Naked Lunch. By the end of the 1960s, the war was pretty much over and the censors had lost. Slowly at first, and then seemingly all at once, profanity found its way into the mainstream. Richard Pryor, George Carlin, Redd Foxx, and other stand-up comedians made it an integral part of their live performances. Carlin’s best-known routine was called “The Seven Words You Can’t Say On TV.” For the most part, TV and radio remained profanity-free environments throughout the 1970s, but many filmmakers, novelists, and stand-up comedians embraced this newfound freedom wholeheartedly. And racial epithets were just a normal part of this new freedom. Tellingly, none of Carlin’s seven forbidden words was a racial slur. That’s because these slurs just weren’t as shocking to people then as they are now. Archie Bunker, the main character on the hit TV show All In The Family, sprinkled his speech with “hebes” and “darkies” and “coons” and “spades” and “spicks” and “dagos” and “Polacks” and many other racial slurs.

Wambaugh was one of the first serious American novelists to take full advantage of this newfound freedom, and he used it to accurately depict the profane way that many big-city cops (and plenty of other people) talked to each other. His cops – be they white, black, Asian, Hispanic, or Jew – all use racial slurs. His books – especially the first three novels – are filled with profanity. Some of that is just garden variety “f” bombs and such. But Wambaugh had a good ear for the poetry of American obscenity, the way it can be used not to poison the discourse but to spice it up. And he understood the way that racial slurs could sometimes be used not to heighten racial tensions between two people but rather to defuse them. In The Choirboys, Wambaugh gives us two LAPD cops named Willie Boyd and Francis Tanaguchi. Willie is Black. Francis is a Japanese-American but was raised in a Hispanic barrio and considers himself more Hispanic than Asian. Other cops refer to this duo as the Spook and the Gook. When other cops direct Asian slurs towards Francis, he usually insists that they should be using Hispanic slurs instead. Francis refers to other Asians as Buddha heads, regardless of their actual country of origin or religion. By the mid 1970s, this type of casual racism was fairly commonplace even in books that weren’t really about race. But Wambaugh’s books are on a whole other level from most pop fictions of the era. That’s because Wambaugh’s first three novels are about race. In fact, the Watts riots seem to have been pivotal to Wambaugh’s decision to become a writer. They are a climactic event in The New Centurions, still loom darkly over the Los Angeles of the early 1970s as depicted in The Blue Knight, and are still being referred to tellingly in The Choirboys, which takes place roughly ten years after the riots occurred. And the racism in those early novels is complicated. Bumper Morgan is clearly a racist, but he is also fond of plenty of non-white people. One of his favorite restaurants is the Geisha Doll, in L.A.’s Japantown. The owners of the restaurant also seem to have a genuine fondness for Bumper. At one point, Bumper notes that most L.A. cops admire the Asian-American community: “Los Angeles policemen are very partial to Buddha heads because sometimes they seem like the only ones left in the world who really appreciate discipline, cleanliness, and hard work. I’ve even seen motor cops who’d hang a ticket on a one-legged leper let a Nip go on a good traffic violation because they contribute practically nothing to the crime rate even though they’re notoriously bad drivers. I’ve been noticing in recent years though that Orientals have been showing up as suspects on crime reports. If they degenerate like everyone else there’ll be no group to look up to, just individuals.” That statement is full of racism but it’s a complicated racism.

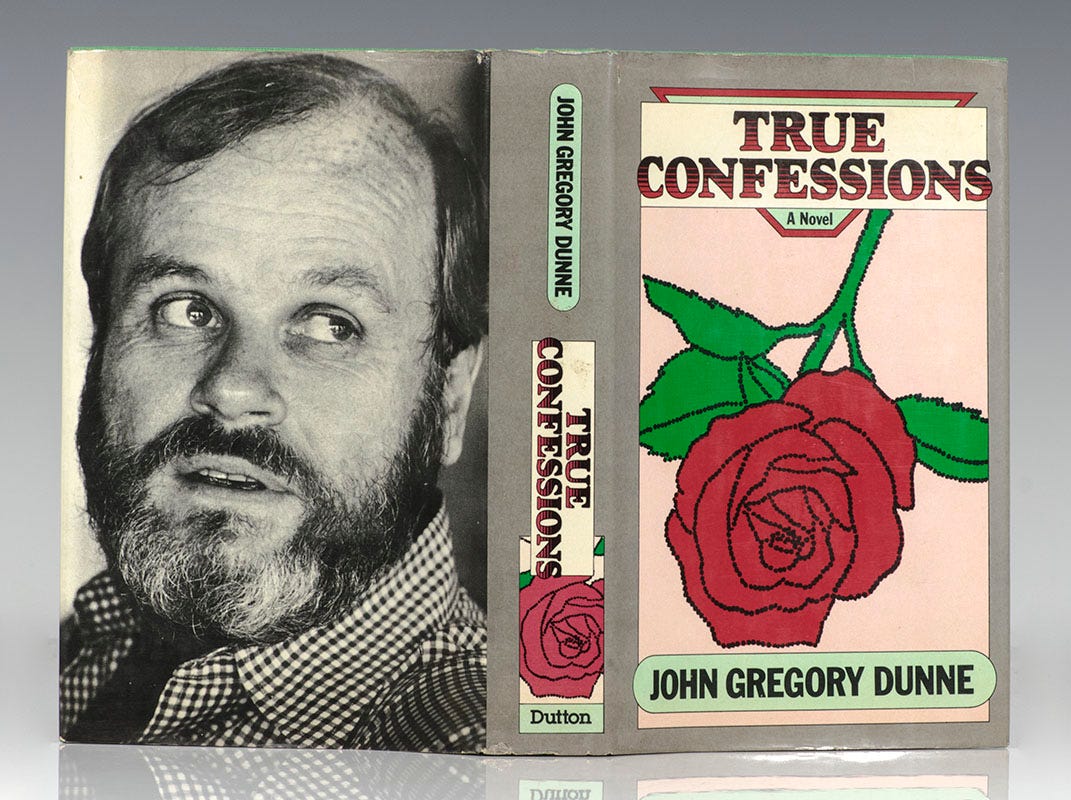

Perhaps the first American writer to be heavily influenced by Wambaugh’s fiction was Joan Didion’s husband, John Gregory Dunne. He once alluded to Wambaugh’s work as an example of “cop tristesse,” or the sadness of being a cop. Up until 1977 Dunne had written nothing but nonfiction. But in that year he brought out his first novel, True Confessions, which reads almost like a mash-up of Wambaugh’s first four books. One of the main characters is Tom Spellacy, a Los Angeles cop of dubious integrity. Like The Onion Field, the story is based on a sensational L.A. crime (in this case, the Black Dahlia murder of 1947). The opening line of dialog (“Imagine a pickaninny mayor.”) contains the kind of racist language associated with Wambaugh’s cops. In the opening scene, Tom Spellacy is in a Chinese restaurant much like Bumper Morgan’s beloved Geisha Doll. The meal, like all of Bumper’s meals, is being comped by the owners. The dialog in that scene refers jokingly to an interracial pair of police partners – “Black and white in a black-and-white” – and seems to be a deliberate effort to evoke Wambaugh’s “the Spook and the Gook.” The other character in the scene is an ex-LAPD officer who was able to retire handsomely because of all the crime he was willing to overlook (for a price) during his career. Before we reach the end of the third page, the two cops have used a total of four different racist terms for African-Americans, and none of them is the n-word (though plenty of those will be forthcoming). As in many a Wambaugh novel, roughly half the cops and crooks in the book are known by a nickname rather than by a real one. An avid pop-fiction fan of the era, reading those opening pages without knowing their author, would almost certainly have guessed that they were written by Wambaugh. Just as Stanley Donen’s 1963 film Charade is often called “the best Alfred Hitchcock film that Hitchcock never made,” True Confessions could be called the best Joseph Wambaugh novel that Wambaugh never wrote.

Alas, by 1975, Wambaugh had pretty much dried up his reservoir of personal experiences that could be turned into bestselling fiction. At that point, he noted in a 2005 essay, “I was forced to do research in order to collect fresh anecdotes and ideas for my fiction.” The first of these researched novels was The Black Marble (1978), which deals with the cutthroat world of professional dog shows (though, thanks to a high-profile dog-napping, LAPD officers figure prominently in the story). The novel is set largely in upper crust Pasadena during the weekend that Super Bowl XI was being played at Pasadena’s Rose Bowl. The book spent eighteen weeks on the New York Times Bestsellers list, rising as high as number three.

After 1980, Wambaugh began to stretch both his geographical range and his subject matter. The Glitter Dome, published in 1981, concerns the murder of a Hollywood studio chief and has as much to say about the film business as it does about the cop business. It spent 22 weeks on the Times bestsellers list. The Secrets of Harry Bright (1985) and Fugitive Nights (1992) are novels set largely in Palm Springs, located 110 miles from L.A. They spoof wealthy Palm Springs residents in much the same way that The Black Marble spoofed their Pasadena counterparts. Finnegan’s Week (1993) and Floaters (1996) are both set in San Diego (by this time Wambaugh and his wife were living there full time).

Wambaugh has also produced some of the best narrative nonfiction books of the last fifty years or so but hasn’t gotten anywhere near the accolades awarded to contemporaries of his such as Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, or Hunter S. Thompson, or to Baby Boomers such as Mark Bowden (Black Hawk Down), Michael Lewis (Moneyball), or Susan Orlean (The Orchid Thief), nor even to GenXers like Lauren Hillenbrand (Seabiscuit). Those writers were mostly associated with impressive east coast publications and elite universities. Wambaugh is associated with Cal State Los Angeles and the LAPD. For all the attention he pays to them in his work, New York City and the Ivy League might as well not exist.

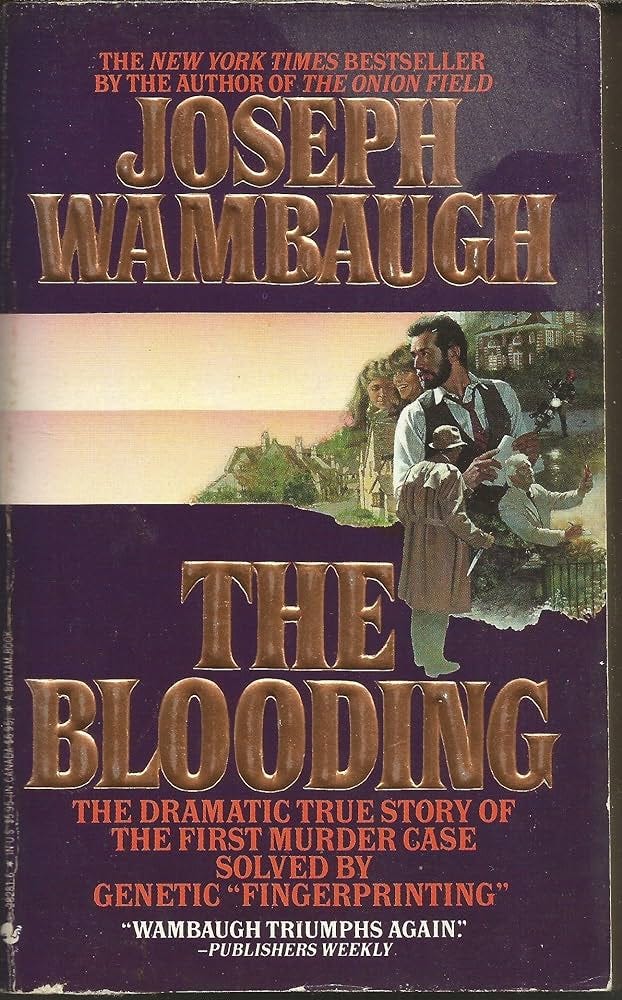

Wambaugh’s nonfiction ventures much farther afield than his novels. Echoes in the Darkness tells of a murdered schoolteacher in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, and the effort to find her killer. The Blooding is set in and around the English village of Narborough. You could reasonably call it the best Michael Crichton thriller that Crichton never wrote. Like Crichton’s 1975 thriller The Great Train Robbery, it concerns an audacious and true-life English crime. And, like Jurassic Park, it was one of the first full-length books to exploit recent scientific advances in the understanding of DNA. Fire Lover (2002) details the hunt for the most prolific arsonist in California history, and Lines and Shadows profiles some of the law-enforcement officers who patrol California’s border with Mexico.

And then, of course, there is The Onion Field. Just as it surprised me two years ago when no one in the media seemed to pay much attention to the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Frederick Forsyth’s hugely influential thriller The Day of Jackal, it surprises me now that the media seem poised to largely ignore the fiftieth anniversary of The Onion Field’s publication. Capote’s In Cold Blood may have been the book that triggered the mid-century boom in true-crime “novels,” but its accuracy came under critical assault almost immediately and it is now known that Capote invented much of his story (he admitted to some of this in the last years of his life). After reading the book, Jack Olsen, one of the masters of the true-crime book, told Esquire magazine, “I know fakery when I see it…Capote completely fabricated quotes and whole scenes…The book made something like $6 million in 1960’s money, and nobody wanted to discuss anything wrong with a moneymaker like that in the publishing business.” The accuracy of The Onion Field, on the other hand, has never been seriously questioned. As Capote’s book was approaching its fortieth anniversary, Hollywood brought forth two films to commemorate the achievement. Capote (2005) starred Philip Seymour Hoffman, who won an Academy Award for his performance, and also featured Catherine Keener as novelist Harper Lee, a lifelong friend of Capote’s. Infamous (2006) starred Toby Jones and featured Sandra Bullock as Harper Lee. Needless to say, no films called Waumbaugh are currently in production. Which is understandable, because Waumbaugh’s life has been largely devoid of the kind of sensationalism that Hollywood seems to prefer in its biopics. Wambaugh and his wife, Dee, have been married since 1955. They produced three children and very little in the way of tabloid drama. But it’s odd that even books that specifically focus on pop-cultural products from Los Angeles in the 1970s often make no mention of Wambaugh.

In 2021, HarperCollins published Ronald Brownstein’s Rock Me On the Water, whose cover explains its thesis: “1974 – The Year Los Angeles Transformed Movies, Music, Television, and Politics.” The book makes no mention of Wambaugh, despite the fact that, by 1974, he had already published three of the decade’s best books – all of them set in L.A. – and had created one of the most talked about shows on television in Police Story. What’s more, his books had already inspired a film, The New Centurions, and a groundbreaking TV mini-series, The Blue Knight.

Fire Lover, published in 2002, would have made an excellent career capper for Wambaugh, a final book that would allow him to retire from writing while still at or near the peak of his powers. By this time, he hadn’t produced a novel since Floaters in 1996 and didn’t plan to write any more. But novelist James Ellroy (L.A. Confidential), a Wambaugh superfan, talked him out of retirement. After the Rampart scandals of 1997 and 1998, the LAPD’s reputation had sunk to an all-time low.

In 2001, the U.S. Department of Justice imposed a federal consent decree on the LAPD, requiring that the department make numerous reforms to its operational procedures and giving the federal government wide-ranging authority to enforce the implementation of those reforms. The decree was lifted in July of 2009, but during those eight years the LAPD underwent dramatic changes. Nearly 1,700 officers left the force (mostly to go to work for smaller and less beleaguered forces). An effort was made to make the LAPD look, at every level, more like the community it served. More minorities and women were brought on board, and more of them were promoted to higher ranks than ever before. Many of these reforms were uncontroversial and highly successful. But some cops – especially longtime veterans – complained that so many restrictions had been placed upon how and when they could use force against a suspect that it had made the job infinitely more dangerous. Ellroy apparently believed that Wambaugh was the only writer with the skill and experience to capture this time of transition in a novel. As it happened, Wambaugh wrote five of them, each of them centered around the LAPD’s Hollywood Station.

Amazingly, these last five novels are pretty much the equal of the five books he produced in the 1970s. And I’m not the only one who thinks so. Of Hollywood Station, Marilyn Stasio, longtime crime-and-mystery fiction reviewer for the New York Times (and occasional naysayer of Wambaugh’s work), wrote: “It’s a serious pleasure to have Joseph Wambaugh back in Los Angeles and writing another blisteringly funny police procedural about the LAPD. While it may have taken him a couple of decades to get his mojo back, after some half-baked books set elsewhere in Southern California, Hollywood Station has all the authority, outrage, compassion and humor of the great early novels (like The New Centurions and The Choirboys) this one-time cop wrote in the 1970s. The formula is familiar, but it still rocks.”

In fact, the Hollywood Station novels seem to be in constant communication with those great early novels. Wambaugh’s centurions, knights, and choirboys were all mostly white, working-class men who lacked a higher education and, often, had served in the military, seeing action in WWII, Korea, or Vietnam. In comparison with those men, the cops in the Hollywood Station series seem to come from an alternate universe. They spend a lot of time worrying about how to pump their breast milk when they are out on patrol. They worry about their gun belts rubbing against their navel rings and irritating the flesh. They worry about bleaching the tips of their hair and getting into the Malibu surf in time to enjoy the “evening glass.” Before frisking a transsexual female, they ask if she is pre-op or post-op. If pre-op (i.e., if she still has male genitalia), she’ll be frisked by a male cop. If post-op, she’ll be frisked by a female cop. These twenty-first-century cops are also, for the most part, much less likely to utter racist epithets or use any kind of force on a criminal suspect. They aren’t necessarily better people than Bumper Morgan (though, thankfully, most of them are), but they are under a microscope to a degree that Morgan couldn’t even have conceived of. Everywhere they go they encounter people with camcorders or cell phones or some other device that can capture the slightest instance of police misconduct. What’s more, thanks to the consent decree, LAPD’s Internal Affairs Group (IAG) is actively trying to weed out bad officers by using tactics that, were they used against a suspected criminal, would be deemed entrapment. One officer notes that, “Being an LAPD cop today is like playing a game of dodgeball, but the balls are coming at us from every-fucking-where.”

I noted that The Rookie, starring Nathan Fillion, owes a great deal to The New Centurions. But it seems to owe even more to Wambaugh’s Hollywood Station books. Fillion plays John Nolan, a former building contractor from Foxburg, Pennsylvania. Foxburg is located about a ninety-minutes drive from Wambaugh’s old hometown of East Pittsburgh. After moving to L.A. and joining the force, Nolan decides to go back to school at the age of 45, hoping that a college degree will improve his chances of promotion. The creators of The Rookie may have gotten that idea from a character in Hollywood Station named Andi McCrea, of whom we are told, “With her forty-fifth birthday right around the corner and her oral exam for lieutenant coming up, it had seemed important to be able to tell a promotion board that she had completed her bachelor’s degree at last, even making the Dean’s List…” Angela Lopez, one of Nolan’s co-workers (played by Alyssa Diaz), is a nursing mother during season four of The Rookie, and has a difficult time both pumping and storing her breast milk at work. Twelve years before The Rookie debuted, Budgie Polk, in Hollywood Station, experienced a similar ordeal. In The Rookie, all of the patrol officers refer to their police vehicles as their “shop.” I first learned about this little bit of terminology in Hollywood Station. Season four of The Rookie included a multi-episode storyline about a respected firefighter who is suspected of being a serial arsonist. This is essentially the tale told in Wambaugh’s Fire Lover. The Rookie doesn’t come close to committing plagiarism. None of its characters appear to be based specifically on any Wambaugh characters. Fire Lover is nonfiction; Wambaugh didn’t invent the storyline. But if, as I suspect, the creator of The Rookie, Alexi Hawley, studied Wambaugh’s work while putting together his own version of the LAPD, he made a smart move. No writer has ever captured the LAPD better than Wambaugh. Most good novels, films, and TV shows about the LAPD seem to have been created and written by people familiar with his books. That doesn’t mean that they always scrupulously adhere to the truth of L.A. police work. Even Wambaugh’s work is filled with exaggerations and far-fetched episodes. But everyone seems to borrow from him.

Throughout his career, Wambaugh has been able to capture his particular segment of the California mosaic with wit and clarity and deadly accuracy. No one ever wrote better about California’s cops and crooks and those caught in the crossfire between them than Wambaugh did. In the forest of California literature, Wambaugh is a giant sequoia. Let’s hope the bowlderizers never get a chance to chop him down.

Thanks. Excellent stuff.

What a great article. My father introduced me to Wambaugh's novels when I was in high school, and he became one of my favorite authors. You're right. Wambaugh does not get enough credit for being one of the first writers to realistically represent the coarse language Americans use. What Norman Lear did for television, Joseph Wambaugh did for literature.