THE LAST GREAT CRIME NOVEL OF 1975

I recently read Quentin Tarantino’s book Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, a novelization of his 2019 film Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood (the ellipses are missing from the title of the book). I can’t tell you how it ranks against other crime novels of 2021 because I haven’t read any yet. But a more important question is how it ranks against the crime novels of 1975. In February of this year, I published an essay here on Substack in which I argued that 1975 was the greatest year ever for crime fiction. And I believe that Tarantino intends for us to treat his novel as though it were an artifact from that year. Why? Let’s look at the clues.

The book, like the film, concerns itself, in part, with the murderous “family” of Charles Manson. The Manson Family came to prominence as a result of nine Southern California murders carried out in July and August of 1969. Since the book provides us with an alternate history of Manson’s clan and their killing spree, it naturally had to be written sometime after 1969. But Tarantino’s book, which was released as a paperback original, doesn’t present itself as a contemporary paperback. In the back pages of the book, we find full-page advertisements for a variety of popular 1970s books: Erich Segal’s Oliver’s Story (published in 1977), Elmore Leonard’s The Switch (1978), and Peter Maas’ Serpico (1973). Anyone familiar with mass-market paperbacks of the era knows that those books usually carried advertisements in their back pages for other recent titles from the same publisher. Usually these advertisements were for titles similar to the one in which the ads appeared. For instance, my paperback copy of William Goldman’s 1974 thriller The Marathon Man carries advertisements in its back pages for Richard Condon’s thriller Winter Kills and Robert Ludlum’s thriller The Rhinemann Exchange, both of which were also published in 1974. In the back pages of a 1977 thriller, you wouldn’t generally find full-page ads for a 1962 romance novel or a 1972 cookbook. Not always, but usually the space at the back of a book was used to advertise books of the same vintage and in the same genre. Which makes the back page material in Tarantino’s novel seem a little inauthentic (which, of course, it is). Tarantino and his publisher (Harper Perennial Paperbacks) are trying to make this novelization look like a relic from an earlier age. Because it carries an ad for a novel (The Switch) published in 1978, we have to assume that this paperback was published no earlier than that. But because Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a paperback, we can assume that a hardback edition must have preceded it by at least a year. It’s true that plenty of paperback originals were published in the 1970s, but these were usually shorter and less ambitious novels. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a fat book with 400 pages of fairly small print. It is an ambitious book with plenty of cultural commentary, lots of character back-story, and a complex plot. This isn’t the type of book that a publisher would normally have released as a paperback original. Therefore, we have to assume that the fake vintage paperback must have been preceded by a fake hardback. So, when was the hardback published?

The Manson Family story gained new cultural currency in 1974 with the publication of Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry’s Helter Skelter, a nonfiction account of the murders. The book was a bestseller and won the 1975 Edgar Award for Best True Crime Book. If Tarantino’s novel had been published in the 1970s, 1975 would have been the ideal year for it to happen. The book is perfectly in tune with the zeitgeist of that year. As noted in my earlier essay, many of the most successful crime novels of 1975 were, like Tarantino’s, inspired by real-life crime stories. These include E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime (the year’s bestselling novel), Judith Rossner’s Looking for Mr. Goodbar (the year’s fourth bestselling novel), and Michael Crichton’s The Great Train Robbery (the eighth bestselling novel of the year). Joseph Wambaugh’s The Choirboys (the fifth bestselling novel) takes place in L.A. and shares a lot of attributes with Tarantino’s book – evil under the California sun, a dark sense of humor, plenty of violence, sexual banter, casual misogyny from the characters, and raw language. I believe that Tarantino and his publisher are trying to pass off this fake vintage paperback as a reprint of a book that had been published in hardback sometime around 1975. (On two or three occasions Tarantino jumps forward to tell us some sad story about what happened to Aldo Ray in 1979 or Cameron Mitchell in the 1980s, but this material probably adds up to less than a full page of text and seems largely superfluous; I suspect that Tarantino included it simply because he had an anecdote he couldn’t resist passing on. Besides, he loves anachronism, as demonstrated by his inclusion of Jim Croce’s 1973 pop single “I Got A Name” in the film Django Unchained, which is set in the 1850s.)

So, viewed as a 1975 crime novel, how well does Once Upon a Time in Hollywood stack up against the rest of the Class of ’75? Could it have stood out in a year so rich in masterpieces? In my opinion, the answer is a resounding yes.

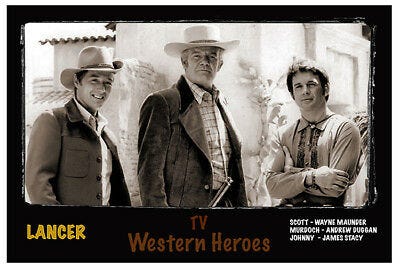

Though literary purists might object, I believe Tarantino’s novel compares favorably with Doctorow’s masterpiece Ragtime. Doctorow’s novel is loosely tied to the real-life murder of famed architect Stanford White, who was killed in 1906 by Harry Thaw, the deranged husband of legendary beauty Evelyn Nesbit, whom White had deflowered when she was still a teenager. Though Thaw and his crimes are mentioned in Ragtime, Doctorow seems much more interested in exploring a particular time (the turn of the twentieth century) and place (New York City and its environs). And he seems most interested in weaving the real-life stories of various celebrities of the era (Harry Houdini, J.P. Morgan, Emma Goldman, Booker T. Washington, and many others) with the fictional stories of his own invented characters. This is pretty much precisely what Tarantino does in his book. He explores a particular time (late 1960s) and place (Hollywood and environs) and weaves the real-life stories of various celebrities (Sharon Tate, Roman Polanski, Bruce Lee, James Stacey, Jay Sebring, and many others) with the stories of his own invented characters. Doctorow is the more careful prose stylist, but there’s something endearing and addictive in Tarantino’s more conversational, expletive-laden, narrative style. It’s like he’s sitting in the room with you, telling a compelling story but interrupting it often to interject equally compelling commentary on movies, music, pop fiction, etc. Tarantino’s prose isn’t as well-behaved as Doctorow’s, but good behavior isn’t everything.

At this late date, younger readers may look at an old hardback copy of Doctorow’s Ragtime – with its ornate lettering and dry, unillustrated cover; the jacket flap copy describing a book set in a long-gone era – and come away with the notion that this was a fairly sedate historical novel. But they’d be wrong. Ragtime is filled with horrific violence, most of it race-related, and it is probably just as relevant to our present day predicament in America as it was in 1975. The well-behaved prose belies an angry, incendiary story about a Black man who retaliates against a racist society by trying to violently overthrow its government. The well-mannered prose works in counterpoint to the ill-mannered behavior of many of Doctorow’s characters.

Tarantino, on the other hand, doesn’t try to keep any kind of a cool distance between the narrator and his characters. Tarantino is, for all intents and purposes, a character in his own book, perhaps the main character. His expositional asides about such things as the films of Akira Kurosawa are as full of foul language as the rants of the characters are. Doctorow’s well-mannered prose was appropriate to the historical setting of Ragtime. But Tarantino’s prose is equally as appropriate to the historical setting of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (whose very title announces – as does Doctorow’s – that the book is historical fiction). And though Tarantino doesn’t foreground racism the way Doctorow did in Ragtime, he does remind his readers that Manson, who was hoping to incite a race war in America, feared and loathed Black men.

What’s more, Tarantino’s prose isn’t at all bad. It’s conversational and often profane, but it also manages to be quite impressive at times. One of the most memorable scenes in the film is the one in which Hollywood stuntman Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) picks a fight with legendary martial artist Bruce Lee on the set of the TV series The Green Hornet. The same scene appears in the book, but here Tarantino slows it down and gives us the thoughts of both Booth and Lee. The men have decided to have a contest. The first one to knock the other on his ass twice wins. In the book we hear Cliff’s strategy running through his head. He decides to let Lee knock him down easily in their first clash. If it happens easily, Cliff figures Lee will get lazy and try the exact same assault tactic the second time around. But once Cliff knows the tactic, he’ll be able to anticipate it and knock Lee on his ass. In the book (unlike the film) we learn that Cliff is a World War II vet who killed more Japanese soldiers in up-close combat (with his hands and a knife, usually) than any other American. He did this mostly in the jungles of the Philippines, in the company of Filipino resistance fighters. He’s killed plenty of dangerous Asians and isn’t even slightly fearful of Lee. But Lee doesn’t know this at first. He attacks and easily knocks Cliff on his ass. And, as expected, he comes back with an identical second assault, but this time Cliff easily defends himself, throwing Lee up against a car and causing injury to the martial artist. Suddenly Bruce understands exactly what has happened, that the first strike was a set up. Here’s Tarantino describing what’s going on in Lee’s head now:

Bruce also quickly recognized that, while Cliff wasn’t anywhere near as skilled as the opponents he fought in any of his martial-arts tournaments, he was something they weren’t.

He was a killer.

Bruce could see Cliff had killed men before with his bare hands.

He could see Cliff wasn’t fighting Bruce Lee.

Cliff was fighting his instinct to kill Bruce Lee.

Lee is right to be afraid of Cliff. In the film it is strongly suggested that Cliff might have murdered his wife. The book leaves no doubt about it. Cliff cut his wife in half with a spear gun meant to kill sharks. And she’s not the only person Cliff has killed since the end of the war. In a flashback to the days when Cliff was newly returned to America after his World War II service (and following a brief stint as a Parisian pimp), Cliff finds himself being threatened in a pizza parlor by two low-level Italian-American goons. What follows is somewhat reminiscent of the legendary “Sicilian scene” in the 1993 Tony Scott film True Romance, which Tarantino wrote. In the Sicilian scene, Dennis Hopper finds himself outnumbered by a gang of Sicilian-American gangsters led by Christopher Walken. He knows they plan to kill him, but he buys himself a little time by telling a story about the evolution of the Sicilian people. At first the story is merely sort of dryly amusing, so Walken lets him ramble on. Eventually though, Hopper turns the story into a slur on the Sicilian race, at which point Walken murders him. The pizza parlor scene in Tarantino’s novelization mirrors this somewhat, but has a much happier outcome for the person (Cliff) telling the story.

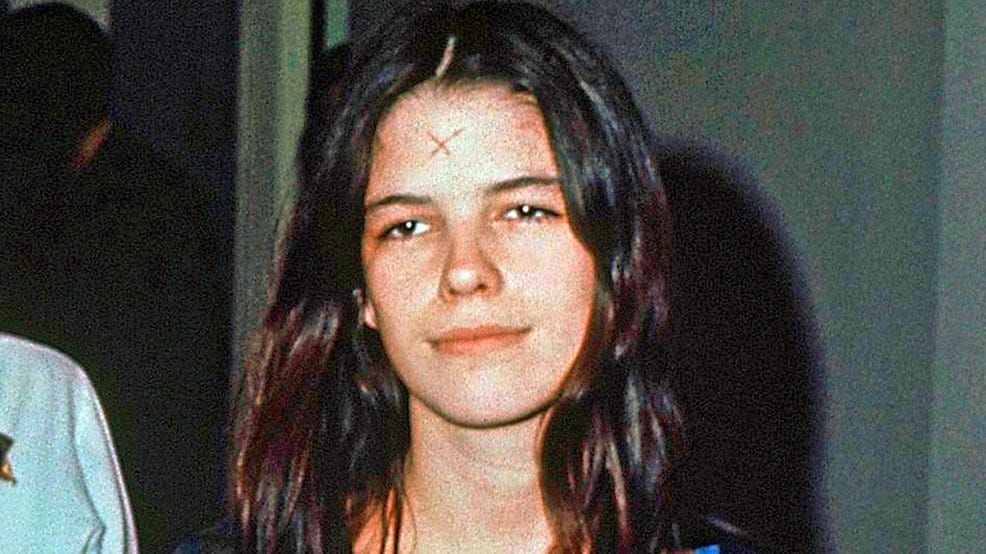

The book abounds with gripping scenes that aren’t in the movie (though they might have been filmed and then cut from it). One such scene takes place between two and three in the morning at an upscale home in Pasadena. Manson has brought some of his acolytes out with him to watch as they put the youngest member of the family, a beautiful teenager named Debra Jo “Pussycat” Hillhouse (a fictional character but probably at least partially based on Leslie Van Houtem — who is pictured above — and played by Margaret Qualley in the film) through an initiation ritual they call “the kreepy krawl.” This involves breaking into an occupied home at night and wandering through it, possibly even interacting with the occupants if they are awake. As the rest of the family stand outside on the sidewalk, Pussycat goes around back, jimmies open the sliding door, and enters the dark and silent residence. The next several pages are very tense. Tarantino does a fine job of demonstrating how thoroughly Manson is able to colonize the minds of his followers. Though “Charlie” remains outside, Pussycat can “hear” him guiding her through the house, admonishing her when she seems about to chicken out. At one point, Tarantino writes, ominously, “She can hear Charlie’s grin in her brain.”

Just as there are scenes in the book that aren’t in the movie, there are scenes in the movie that aren’t really in the book, including perhaps the biggest scene of the film. In fact, this is Tarantino’s gutsiest move. The film’s climax is a scene in which Rick Dalton, Cliff Booth, and Booth’s dog Brandy violently dispatch with several Manson Family members who have broken into Rick’s home. We get a brief mention of that episode early in the book but it isn’t dramatized and never comes up again. The book arrives at an ending that employs something rarely seen in a Tarantino film: subtlety. The book’s ending is soft, moving, and sweet.

One of Tarantino’s most impressive feats is the way that he turns the plot of the pilot episode of Lancer into a novel-within-a-novel. Lancer was an actual short-lived (two seasons) TV series that debuted in 1968. In both the film and the book, many of Rick Dalton’s scenes concern his guest-starring role in the Lancer pilot, in which he plays a villain named Caleb DeCoteau (Rick think the last name is pronounced “Dakota”). In the film, we’re told very little about the TV series. We know it is a Western drama but we aren’t told much about the time or the place. We don’t know the back-stories of its characters. In the novelization, Tarantino gives us a complete panoramic Western tale that explains how Caleb DeCoteau came to cross paths with Johnny Madrid, the half-Mexican bastard son of Murdoch Lancer, a fabulously wealthy cattle baron who owns a massive Texas ranch somewhere near the Mexican border. Mind you, Tarantino doesn’t treat this as fictional material but as a parallel story running alongside the contemporary one. True, it is sketched out in the manner of a film treatment or a cheap novelization but, quite obviously, those aren’t genres Tarantino considers beneath him. And one of Tarantino’s most brilliant novelistic devices is the way that he is able to merge the two stories – the tale of Rick Dalton and the tale of Caleb DeCoteau – into one as the book comes to a close.

Although I loved Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, that may have something to do with my age. Tarantino and I were both born near the end of the so-called Baby Boom era (1946-1964), he in 1963, and I in 1958. And we grew up addicted to many of the same films, TV shows, pop fictions, pop music, etc. This is much more common among Baby Boomers, who had only three TV networks and a handful of radio stations to choose from, than it would be among Millennials or GenZs, who have so many streaming options to choose from that a dozen of them could watch five or six hours of TV a day without any two of them ever seeing the same program. Much of what I enjoyed about Once Upon a Time in Hollywood were the many cameos involving celebrities from my youth, people such as Robert Conrad (star of The Wild Wild West), Otto Preminger (an esteemed film director but first known to me as Mr. Freeze on Batman), Dennis Wilson (drummer for The Beach Boys), Pete Duel (co-star of Alias Smith and Jones), and many others. The book is also filled with references to Elmore Leonard, T.V. Olson, Marvin H. Albert and many other pop-fiction writers whose works I eagerly devoured back in the day. As a teenager I felt guilty about enjoying the music of The Monkees more than the music of The Beatles, but Tarantino convinced me (through his loving portrait of Sharon Tate) that this wasn’t uncommon. Will a 25-year-old reader who has never heard of the pop group Paul Revere and the Raiders enjoy Tarantino’s book as much as I did? Hard to say. I read Ragtime back in 1976 when it first came out in paperback. I found it a chore to get through. I re-read it last year, while researching my essay about the crime fiction of 1975, and found it brilliant. In 1976, I had never heard of Evelyn Nesbit or the Stanford White murder or most of the other people and events referenced in the book. Over the subsequent 45 years I’ve learned much about American history that I was never taught in school. And so, naturally, I derived much more enjoyment from Doctorow’s novel. When Ragtime was published, the events it depicted were 69 years in the past. The events depicted in Tarantino’s book are now 52 years in the past – pretty much ancient history from the perspective of a Millennial. But because much of the pop cultural material described in Tarantino’s book is preserved on film or audiotape and is easy to access – the movies of Roman Polanski, the music of The Beach Boys and The Monkees, old TV shows like Mannix and the FBI – it might not seem quite as remote to today’s twenty-somethings as the trial of Harry Thaw seemed to me back in 1976.

But how might Tarantino’s novel have fared had it been published in 1975, crime fiction’s annus mirabilus? Well, a lot depends on how it was presented to the public. If it had been brought out by a major New York publishing house and given plenty of promotion – just as Ragtime, Mr. Goodbar, and The Choirboys were – I’m convinced it would have been a sensation. Readers whose minds had been blown in 1974 by the incredible forensic detail of Helter Skelter, might have been in need of a good alternative history, a book that posits what might have happened if an alcoholic, has-been TV star and his stunt double had somehow managed to kill off a few of the Manson family before the group could wreak the havoc for which they became notorious. Don’t forget, it was on September 5, 1975, that Manson follower Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme attempted to assassinate President Gerald Ford in a Sacramento Park located about a mile from where I sit. Fromme is an important secondary character in both the Tarantino novel and the film that preceded it (in which she was played by Dakota Fanning). That event in and of itself might have sent people scrambling to their local bookstores to see how she fared in Tarantino’s alternate history. Otto Preminger was alive and well in 1975. In fact, his crime film Rosebud was released that year. He would probably have bristled to see how he was portrayed by Tarantino, and that would have drummed up publicity for the book. Likewise, Robert Conrad was still very active as a TV actor in 1975. In Tarantino’s book he’s portrayed as a jerk who often “forgets” to pull his punches when swinging at a stuntman he is staging a fight with. That, too, might have generated publicity for the book.

Had the book been properly handled by its publisher in 1975 I feel confident that Once Upon a Time in Hollywood would have made Publishers Weekly’s list of the year’s ten bestselling books in America, knocking Saul Bellow’s Humbold’t Gift off the list completely. And good riddance to Saul Bellow. There isn’t a flame-thrower to be found anywhere in the work of that second-rater.

I can’t say that Tarantino is as good a novelist as he is a filmmaker, but that’s only because he is an excellent filmmaker. But as a writer of film novelizations? Well, with his very first effort he may have just established himself as the greatest of all time.