WARNING: Spoilers ahead.

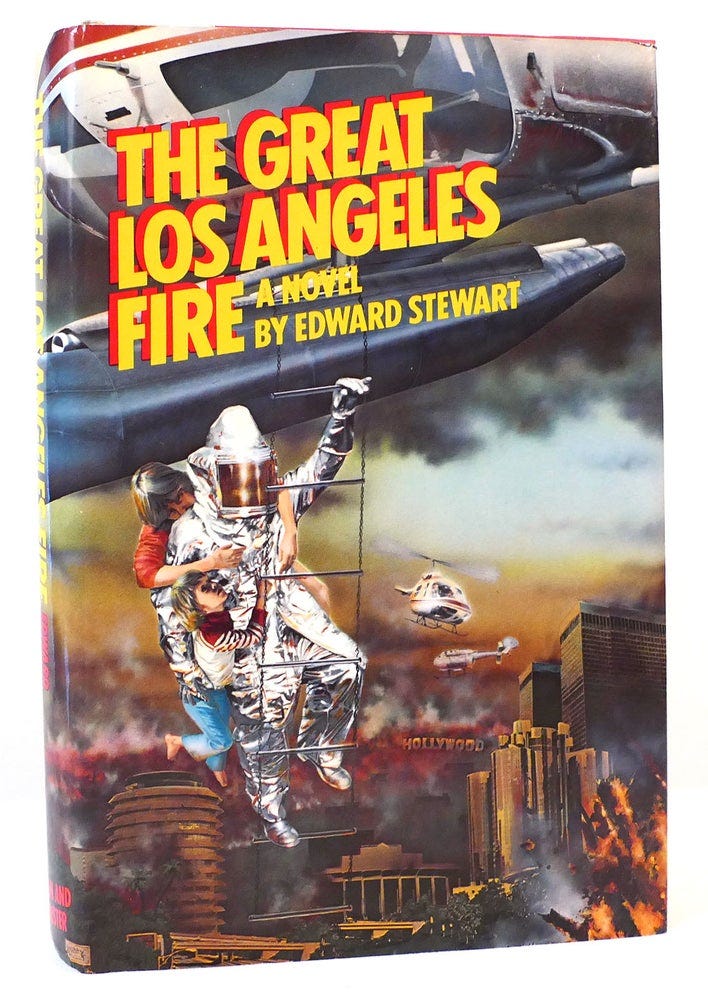

No this is not an essay about the fires that are currently ravaging Los Angeles County. I love L.A. and I am saddened by the disaster currently unfolding there. But this essay isn’t about the real Los Angeles. It is about a 1980 novel called The Great Los Angeles Fire, written by Edward Stewart and published in hardback by Simon and Schuster.

Stewart (1938-1996, and pictured above) was a highly educated (Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard University) American author, who was born in New York City and, after graduating from Harvard, studied music in Paris, where he also worked as a composer and arranger before switching gears and pursuing a career as a novelist. His first novel, Orpheus on Top (1966), had literary pretensions and sold poorly. After that, he seems to have made a conscious decision to court fame and fortune by writing in a more popular vein of fiction. At that point he started churning out titles like They’ve Shot the President’s Daughter (1973), For Richer, For Poorer (1983), and Privileged Lives (1988). His best novel was probably Ballerina (1979), a soapy and trashy inside look at the high-pressure world of professional ballet dancers, with plenty of backstabbing and sex to make it all go down easily. Much of his work seems to have been written to try to cash in on some pop-cultural vogue or another. They’ve Shot the President’s Daughter, for instance, might have been inspired by the success of Robert Serling’s 1967 novel The President’s Plane is Missing, Fletcher Knebel’s 1968 novel Vanished, and the many subsequent political thrillers of that ilk that proliferated in the 1970s. Ballerina was probably inspired by the success of the 1977 Herbert Ross film The Turning Point. For Richer, For Poorer may have been inspired by Irwin Shaw’s 1969 novel Rich Man, Poor Man (source of a wildly successful 1976 TV miniseries) and the many other novels of dynastic wealth that proliferated in the 1970s. Late in his career, Stewart seemed to have noticed that pop-fiction fans were fond of crime-book series, and so he created Vincent Cardozo, an NYPD detective, and wrote four novels about him. The books have been compared to Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct series. For all of his pandering, however, Stewart never seems to have produced a genuine bestseller. His biggest failing, I believe, was simply that he was too sophisticated and snobbish to really embrace pop fiction whole-heartedly. His books seem to occupy an awkward space somewhere between midlist literary fiction and genuine pop-fiction bestsellers. He probably should have leaned more heavily into the sensationalistic aspects of his stories. He never really had a shot at being another John Updike or Philip Roth so he should have just gone all Dean Koontz on us.

The Great Los Angeles Fire was almost certainly written to cash in on the success of the disaster novels and movies that were all the rage in the 1970s and 1980s: The Poseidon Adventure, The Towering Inferno, Airport, etc. The novel’s most obvious forebear is the 1974 Mark Robson disaster film Earthquake, in which a catastrophic earthquake levels much of Los Angeles. Stewart seems to have thought that by combining parts of The Towering Inferno with Earthquake he could produce a surefire bestseller. Alas, the book never (you should pardon the expression) caught fire. I read it years ago and promptly forgot about it. I re-read it just recently to see if it might have anything interesting to say about the fires currently wreaking havoc with Los Angeles and environs. Here’s how the book begins:

Los Angeles is a city with a forest inside it. See it as hills and canyons and mountains and woods in and all around an urban and suburban complexity that is vast and never lets up. There are no boundaries to go by: housing and commerce thrive anywhere here – even on the dreary desert scruff. So forget anything that comes close to exactitude and settle instead for an impression.

A crescent—that’s the impression. That’s what Los Angeles is. See it as a crescent. See it as a crescent that has turned its back on the rest of the continent. See the points of the crescent touching the Pacific, water filling the concavity from top to bottom.

Keep your eye on that crescent, on the sea caught in its scoop. It’s like a skinny man all bent over, and heaped up there against his back is mountain and forest from top to bottom…Like all the hills and forest that thread through and around the city, it is dry kindling…But this is not ordinary kindling: it contains its own fuse, the flammable resin of the pines.

There you have it: the kindling, the fuse; the city surrounded and penetrated.

Today, September 7, at 6:00 p.m., with the hot dry Santa Ana wind lashing across the hills, there is only one thing missing.

The spark.

That spark is four hours in the future, and once it touches the kindling and the fuse, the thing that the city does not yet even suspect will become the horror that it will never forget.

That’s not bad as thriller-novel openings go. Stewart’s novel definitely has its virtues. And it did managed to predict some of the fallout from a major fire such as the one menacing L.A. this week. Just today, Substack pundit Noah Smith published an essay in which he complained that:

“Public social media – X, Reddit, Bluesky, and so on – has changed how we think about disasters. On the one hand, because it floods us with information, it gives us the ability to draw reasonable, well-informed conclusions about terrible events much more quickly and arguably more easily than we could in earlier times. On the other hand, the inevitable flood of misinformation and opportunistic politicking that inevitably accompanies any disaster raises our chances of being rapidly misinformed and makes any calamity more socially divisive than it would have been before.

Compare the reactions to the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake – the first major natural disaster I can remember hearing about – with the reaction to the horrific wildfires burning through Los Angeles today. Back in 1989, the news responded to the earthquake for the first few days by simply showing photos and videos of the damage, telling stories about the victims, and generally just saying, “Oh, what a terrible disaster.”…In contrast, the social media reaction to the 2025 wildfires – which have already claimed five lives, left thousands homeless, and cost tens of billions of dollars – has featured all the finger-pointing and false rumors that we’ve come to expect from every big negative news event in America.”

I like Noah Smith but I think he’s wrong about this. Major American disaster have been cynically politicized for as long as I have been alive. Edward Stewart knew this, and in his novel, he shows how it worked in a pre-social-media era. As L.A. residents wake up to the news that wildfires are threatening the city, VV Cameron, the host of a sleazy TV tabloid program, greets her audience with this populist rant:

“While you slumbered Los Angeles, your backyard was going up in cinders. Yes, it’s happening right up there in the Santa Monica Mountains, and the Santa Susanas, and the San Gabriels. Film notables are this very minute running for their lives and leaving their million-dollar bungalows behind for the insurance companies to fret about. But it’s not those pampered prima donnas and Donalds of Tinselwood that are the stars in my book. It’s you, the card-carrying Californians that care about this city – because you’re the ones that have got to live here and make this city work. You and me, Los Angeles, we’re not hopping a Concorde to Rome or Acapulco when the whole kit and caboodle burns down. We’re stuck with L.A., holocaust or not, it’s ours! So here are a few questions I want you to consider: Is there any city in the world that has battled as many blazes as many times as we have? The answer is no, my friends, and you know it. Yet what are we doing about it? Are we protecting the lives of our families and loved ones? Are we building more fire stations? Are we putting in hydrants where there are none for blocks and blocks and blocks? We are not my friends. And why? Because your elected political leaders have the idea that fire stations and fire hydrants are unsightly! Oh, no, innocent bystanders, your political leaders don’t want those unsightly fire stations and fireplugs that could save the lives of your children! And here’s one more fact: cities all over the world, cities everywhere in these United States, have passed laws against roofs made out of flammable material – but have we, my friends? We have not.”

Even before the advent of Facebook and Twitter, we had talk radio and tabloid TV to help fan the fires of disaster opportunism.

Stewart’s book also has plenty of information about what makes the Los Angeles area so prone to catastrophic fires: “You have to remember,” says one character, “the Los Angeles region has the fastest-burning ground cover in this part of the hemisphere. What with wind and drought, like we got now, fire could go through that grass and brush at sixty an hour easy. See, when it comes to fire, it’s the speed that counts, you know what I mean? The faster the fuel burns the hotter it gets and more people are killed by heat than by fire itself. The heat scalds your lungs, know what I mean?”

But the fire in Stewart’s books differs in one significant way from the fires currently destroying much of Los Angeles. The real life fires appear to be a natural disaster. The fires in Stewart’s book were all set deliberately by one man, a disgruntled Vietnam War vet (a ubiquitous stereotype in the pop cinema, fiction, and television of the era) named Frank Venice aka Frank Defino. Frank was an Army technician who specialized in incendiary devices. He was burned hideously in an explosion. Now he is out of the military and wants to make somebody pay for what happened to him. He has decided to restage the WWII firebombing of Dresden in 1980’s Los Angeles. Because of its geography – surrounded on three sides by mountains and on the fourth side by an ocean that frequently serves as a highway for strong easterly breezes that don’t allow smog and smoke to escape the valley – Defino believes that L.A. is ideally suited for a massive firestorm. If he sets the crescent of forests and mountains that surround L.A. alight when a strong easterly breeze is blowing, he believes he can incinerated the entire city, with the mountains acting as a smokestack and the valley as the fireplace.

Defino’s plan for setting off multiple fires at once in critical locations is an evil one (as well as somewhat ludicrous). It may also explain why the book never became very popular. Defino adopts homeless dogs from a local shelter and drugs them. Then he ties an incendiary device to their leashes. These mini firebombs have fuses that are triggered by sunlight. So the dogs are set into the wilderness area at night. Because they are drugged they sleep until the sun rises and…well, I’ll let the L.A. Fire Chief explain it to you: “He’s leashing the dogs with light-sensitive fuses. The sun comes up, the fuse ignites, sets off the bomb, releases the dog. The dog runs in panic and the bomb gets dragged ten yards or so before the fuel’s used up. By then, the forest’s on fire.”

Leaving aside that probably no expert in incendiary devices would ever try to burn down an entire city using a method so fraught with unpredictable elements, I’ll let bestselling novelist Tess Gerritsen explain to you why Stewart’s doggie-dependant disaster story was a commercial misstep. This is from her online blog:

Every thriller writer knows you must never, ever kill a pet in your novel. You can torture and mutilate any number of human beings. You can slice and dice women, massacre men on a battlefield, and readers will keep turning the pages. But harm one little chihuahua and you’ve gone too far. The readers will let you have it.

I learned that lesson the hard way when I wrote PLAYING WITH FIRE, about the fate of a Jewish-Italian family during WWII. What upset readers wasn’t the tragic fate of the doomed young lovers, or the fact the family perishes in a Nazi death camp. No, what really outraged them – and boy, did they vent their outrage in emails, reviews and reader forums — was the death of a fictional cat. In a novel about the Holocaust.

I was certainly aware that animal deaths are a trigger point in fiction, even for hardcore thriller readers, but I assumed horror movie fans were a tougher bunch. After all, they’re accustomed to zombie apocalypses and oozing brains and fountains of blood. Surely they can handle the death of a yappy little terrier.

Or so I thought when my son Josh and I made our low-budget horror film “Island Zero.” Set on a remote Maine island at Christmas, the movie’s about a small fishing community that finds itself cut off from the outside world when the ferry suddenly stops coming, and no one knows why. The phones are dead, the power’s out, and every fisherman who tries to make it to the mainland vanishes. When horribly mutilated bodies start to turn up along the water’s edge, the survivors realize that someone – or something – is hunting them. Without the budget for big-studio CGI or elaborate creature effects, we focused instead on a character-driven plot. Inspired by wintry Scandinavian films, “Island Zero” is very much about the villagers and their personal crises. The story is a slow but inexorable buildup to terror. Would a horror audience sit through a film where the blood doesn’t start spilling until the second half? How could we goose the scare factor early in the story?

We chose to add a cold open before the opening credits. This introductory scene is the equivalent of a prologue in a novel, and it gives the audience a taste of the scares to come. We had access to a sailboat and our producer found a scene-stealing terrier named Henry, who made his big-screen acting debut playing the very first victim. Henry happily dove right into the job, yapping on cue as we filmed his gruesome cinematic fate. Problem solved!

Or so we thought.

Not long after the film was completed, I got an urgent call from my friend Dan Rosen, a screenwriter who’d watched “Island Zero” at a film festival. “You can’t kill the dog! You’ll piss off the audience and they won’t sit through the rest of the movie because they’ll still be thinking about the dog!” He implored us to get rid of the cold open before we officially released the film.

I worried that Dan was right, but the rest of the “Island Zero” team adamantly refused to cut the cold open. They told me that horror audiences are tough, they want a jolt of adrenaline in the first three minutes, and a focus group who’d watched the film never raised any objections to the dead dog.

Reluctantly I agreed to keep the cold open.

A few months later, our distributor Freestyle Media released “Island Zero” on multiple streaming platforms. The very first week, it hit the top ten in horror films on iTunes, which was astonishing for a low-budget film by first-time indie filmmakers, and it picked up review attention from dozens of horror film critics. But it soon became clear that the dead dog was shocking viewers. Even gore-hardened horror audiences have trigger points, and one thing that really triggers moviegoers is dead pets. It’s such a sore point there’s even a website called DoesTheDogDie.com, which warns audiences which movies to avoid.

With our very first scene, we had broken one of Hollywood’s biggest taboos – a taboo so universally known that Blake Snyder’s classic book about screenwriting is called Save The Cat. When the fate of a dog named Boomer is unclear in the space-alien movie “Independence Day,” audiences sent an avalanche of angry letters in protest. (The alien attack wipes out entire cities and millions of people, but it was the dog’s fate that really upset them.)

***

Stewart’s novel, The Great Los Angeles Fire, has a title that seems to have been ripped from today’s headlines, but his was hardly the first novel to deal with fires as a dangerous fact of life in Southern California. One of my favorites is Shirley Streshinsky’s 1981 Malibu historical novel Hers The Kingdom. Barry Kaplan’s 1983 novel, That Wilder Woman, also incorporates a massive Malibu fire in its plot, as does Taylor Jenkins Reid’s more recent (2021) novel Malibu Rising. Dozens, if not hundreds, of novels have been written about fires and the Los Angeles area. The Great L.A. fire of 2025 is sure to inspire dozens more. Joseph Wambaugh’s 2002 nonfiction book Fire Lover, reads like a great L.A. fire novel. And, though it is set in Northern California, George R. Stewart’s 1948 novel, Fire, is probably the granddaddy of all California fire novels.

But if you are looking for something truly different, I suggest that you check out Thom Racina’s 1977 novel The Great Los Angeles Blizzard. Racine’s book imagines just how a sudden, unanticipated blizzard might bring Los Angeles to its knees. It’s a very original concept. Let’s hope that it never comes true. Although, right about now, most Los Angelinos might just welcome a blizzard.

Apparently at least one of the fires was set deliberately. But not by a crazy idiot and his dogs.