THE EX – A NOVEL BY ALAFAIR BURKE

Some spoilers ahead.

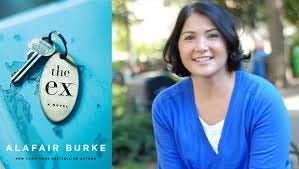

Last week I posted a review of the new Amazon Prime miniseries The Better Sister. While I found parts of the series enjoyable, I had nothing good to say about the show’s depiction of how a murder trial is conducted. The Better Sister is based on a novel of the same name by Alafair Burke (pictured above), a Stanford-educated attorney and law professor with plenty of experience in criminal trials. Thus I assumed that the miniseries’ ludicrous portrayal of the judicial system was the fault of the TV showrunners and not of the source material. At that point, I had never read a novel by Alafair Burke, but I assumed that no one with her legal background could be responsible for such laughable courtroom scenes. It turns out that I was right.

Over this last weekend, I read Burke’s 2016 legal thriller The Ex, and I thought it was excellent. In fact, the book is more of a legal procedural than a legal thriller. It wasn’t filled with gunplay and car chases and murder. The only murders dealt with in the book occur before the story begins. The novel largely concerns itself with how a complex murder case wends its way very slowly through the judicial process. This stands in sharp contrast to Amazon’s The Better Sister, in which the murder trial appears to begin mere days after the murder is committed. In The Ex, three people are shot dead in a recreational area along a New York City waterfront park on the morning of June 17, 2015. The story begins a few hours later as the police are interviewing Jack Harris, a successful novelist who was at the park and believes he is being questioned as a possible witness to the murders. Actually, the police suspect him of having perpetrated the murders. And in a short while, they will arrest him and lock him up.

Jack is a widower with a sixteen-year-old daughter, Buckley. His daughter still struggles emotionally as a result of her mother’s murder (in an apparently random mass shooting incident), which occurred years earlier. For Buckley’s sake, Jack doesn’t want to spend so much as a night in prison, much less the rest of his life. So he calls upon an old girlfriend, Olivia Randall, whom he hasn’t seen in nearly twenty years but who has become a top New York City defense attorney in the interim. Jack’s history with Olivia is fraught with emotional baggage. They were engaged to be married until he came home to their apartment one day and discovered evidence that she had just engaged in sex with another man. Distraught, Jack went to a bar and called his only brother, Owen, and asked him to join him for a few drinks. While commiserating with Jack, Owen drank way too much and died in a drunk-driving incident on his way home. Thus, Olivia is linked in Jack’s mind not only with a failed romance but also to Owen’s death. Nonetheless, he needs help, isn’t particularly wealthy, and Olivia is the only criminal defense lawyer he has any connection to.

With great reluctance, Olivia agrees to represent Jack. Her first big hurdle is Jack’s bail hearing. In real life (unlike in TV shows such as The Better Sister), a multiple murder case like Jack’s could take years to reach trial. And, unless the judge sets bail for him, Jack would have to spend those years awaiting trial in a jail cell. Scott Temple, the ADA who will be prosecuting Jack, doesn’t bother attending the bail hearing, assigning it instead to a less experienced ADA named Amy Chandler. Temple knows that, in New York City and probably every other city in the U.S., a subject accused of gunning down three people in a public square is an unlikely candidate for bail. No judge wants to release a suspect on bail only to have him go out and commit another senseless mass murder. But Temple has made a critical mistake by assigning the bail hearing to Chandler, who has been an attorney for only six years and has nowhere near as much criminal trial experience as Olivia Randall. Had Temple appeared in person, Jack would probably never have gotten bail. But Burke does a good job of showing how a shrewd defense attorney can outmatch a less-experienced ADA in court. Olivia makes sure that Buckley shows up in court, looking particularly youthful and woeful and in need of her father. Olivia also marshals evidence to point out how weak the prosecutor’s case against Jack is, relying almost exclusively on circumstantial evidence. She also presents evidence that several other people had at least as much motive as Jack did for wanting to commit the murders. Amy Chandler, relying on the judge’s natural reluctance to release someone suspected of such a heinous crime, hasn’t prepared herself for this onslaught and gets steamrolled by Olivia, who manages to secure bail for Jack. This is just one of many examples in the novel of Alafair Burke using the legal process itself (not some fictional, Hollywood-ized version of it) to create compelling drama. Who needs car chases and shootouts when you know how to squeeze excitement from the real-life processes of the legal system?

In The Ex, Burke not only demonstrates how the judicial system works in real life, she also bluntly contrasts it with the way it is portrayed by Hollywood. Here’s an example of that: “One of the great myths about criminal cases is that prosecutors have to give defense attorneys access to all their evidence. Don [Olivia’s law partner] called it the nonexistent ‘law of Cousin Vinny.’ In reality, prosecutors were generally allowed to keep the defense in the dark until we got closer to trial, but had to turn over ‘material, exculpatory evidence’ – called Brady evidence. They could keep the stuff that might hurt us long as they turned over the big stuff that might help us.”

The bitter fight between prosecutor and defense attorney over disclosure rules takes up a good deal of space in The Ex. At one point Olivia accuses Temple of turning over exculpatory evidence to the defense but burying it in so much excess material that looking for the exculpatory part is like seeking a needle in a haystack. For instance, Temple turns over reams of subpoenaed phone records which he claims contains exculpatory evidence, but he doesn’t tell her what the evidence is. The defense team is forced to track down hundreds of phone numbers in order to find the single phone call that might help their case. This is apparently a fairly common practice by real-life prosecutors though not within the spirit of the law. It is also far more fascinating than the type of Perry Mason nonsense found in most TV legal dramas.

Also interesting is the haggling that occurs over the fact that, after his arrest, Jack’s clothes and hands were tested for gunshot residue (GSR). The test found GSR on Jack’s shirt but not on his hands. Olivia argues that this evidence should be suppressed. She points out that police officers regularly take target practice at a shooting range. Since Jack spent a good deal of time in the police station, rubbing shoulders with cops and criminals, his shirt could have picked up GSR even if he hadn’t been handling a weapon lately. Olivia believes that the fact that Jack’s hands tested negative for GSR proves that he couldn’t have handled a gun that day. The prosecutor argues that Jack could easily have washed his hands after the shooting. But washing his shirt immediately afterward would have been more difficult. None of this discussion takes place during an actual trial or before a jury. These things are argued as preliminary motions in front of only a judge, who will ultimately decide what evidence a jury will be allowed to see at trial. Burke does a good job of showing how much of the actual legal battle takes place long before a court date is set and a jury is selected. The battle to determine what evidence will be allowed and what evidence will be suppressed is probably as important, if not more so, than anything that will be argued before a jury. Burke describes the process this way: “The march toward a criminal trial is slow but never steady – fast and frenetic at the beginning, followed by a long period that would feel almost normal if not for the pending charges, followed by the ramp up toward trial.”

Months after Jack is arrested, a trial date hasn’t even been set, which is fairly normal in a complicated criminal trial. But Burke manages to make all of the pretrial maneuvering fascinating. I have to assume that her novel The Better Sister is as realistic as The Ex in its portrait of how a criminal case moves towards trial. Thus, it is a shame that the people who adapted it for TV didn’t remain more faithful to their source material.

The Ex has a lot more going for it than its verisimilitude to real life. Burke has fashioned a story that delves into not just one mass shooting in New York City but two of them. She has peopled her novel with interesting characters and provided them with plenty of backstory. Frequent flashback sequences provide the book with an engrossing second storyline, one that details the birth and death of the long-ago romance between Olivia and Jack. Burke also demonstrates how a catastrophic event can be triggered by far more mundane events (a missed train, an ill-advised sexual liaison). She provides various Hollywood style plot twists, but these are always foreshadowed and never come completely out of the blue. But even if you are able to anticipate all of the novel’s major plot twists, the story won’t be spoiled for you, because the real fun of reading The Ex comes from watching (what I assume is) a fairly accurate portrait of highly skilled attorneys trying to navigate the Byzantine labyrinth of the contemporary American judicial system. If you enjoy watching top-notch professionals operating at the top of their game, then you might want to seek out some legal thrillers by Alafair Burke. I’ve already got a few others lined up on my nightstand.