THE BETTER SISTER AND OMEGA: MORE ABOUT COMPETENCE PORN

This post contains numerous spoilers for the TV series The Better Sister.

My wife and I recently binged the new Amazon Prime miniseries The Better Sister, a legal thriller based on a novel by Alafair Burke. I enjoyed it because it starred Jessica Biel and Elizabeth Banks, two actresses I love. Julie enjoyed it because it also featured Corey Stoll, an actor she loves. It also featured Kim Dickens, essentially reprising her great performance from the film Gone Girl. The series has much to recommend it. But, alas, as a legal thriller, it falls short. It provides some thrills, but its portrait of the legal system seems ridiculously flawed. I am not a lawyer. I have no legal training. I am sure that plenty of eye-rolling inaccuracies slip past me all the time when I read or watch a legal thriller. But if the inaccuracies are so glaring that even an idiot like myself has trouble swallowing them, the novelist or the scriptwriter has clearly failed at one of their main tasks: to make the legal maneuvering at least marginally believable. There are plenty of eye-rolling inaccuracies in The Better Sister. I am going to assume that these are the fault of the TV scriptwriters, because Alafair Burke, in addition to being the daughter of crime writer James Lee Burke, is a graduate of Stanford Law School, a professor of law at Hofstra University, and a former assistant district attorney for Oregon’s Multnomah County, a region which includes Portland.

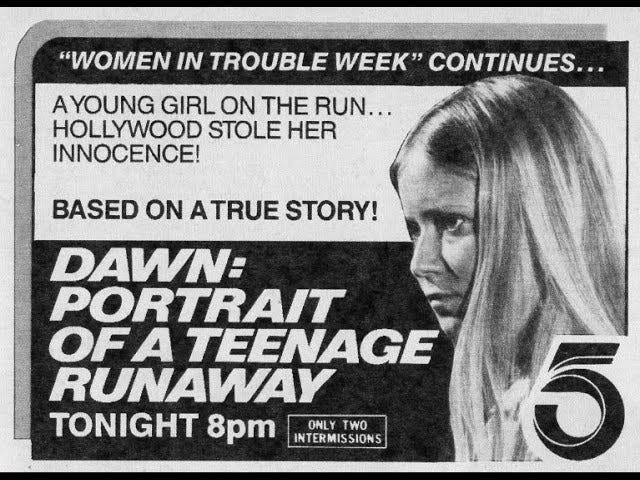

The Better Sister is another of those eat-the-rich dramas (The White Lotus, Sirens, The Perfect Couple, Big Little Lies, The Undoing, etc.) that seem to be ubiquitous on TV these days. Essentially, these programs pose as critiques of the miserable lives that uber rich Americans lead while all the while allowing the audience to wallow vicariously in the luxury of it all. These shows work in much the same way as Clint Eastwood’s classic 1992 western Unforgiven does. While purportedly delivering an anti-violence message, the film caters to the audience’s desire for violence. It also recalls all those Portrait of a Teenage Runaway TV dramas of the 1970s that purported to be a condemnation of the people who exploit underage girls for sex but which nonetheless pandered to the audience’s prurient interest in underage girls having illicit sex, thus further exploiting a vulnerable population. This type of hypocrisy is fairly common in popular entertainment and doesn’t bother me much. I can enjoy a violent movie even when it preaches anti-violence. I can enjoy real-estate porn even when it is cloaked as a cautionary tale about what happens to people who lust for luxurious living. I can even enjoy a good teenage sex drama even when it poses as a condemnation of people who are interested in teenagers having sex.

But The Better Sister is another of those dramas, like The Perfect Couple, in which extremely wealthy and sophisticated people seem to have no idea that, for instance, they are not required to talk to the police under any circumstances, or that they have the right to have an attorney present during questioning if they happen to be dumb enough to want to talk to the police. In The Better Sister, Jessica Biel plays Chloe Taylor, the successful editor of a prestigious national women’s magazine called The Real Thing. She is married to Adam MacIntosh, a lawyer (played by Stoll) who has worked both as a prosecuting attorney and as a partner in an elite New York corporate law firm. Clearly Chloe, who is portrayed as whip smart, has heard of her Miranda rights. But when Ethan, her 17-year-old son, is suspected of murdering his father, Chloe willingly goes down to the police station and blabs on and on to a couple of hostile detectives about the killing, and even allows the police to photograph the scratches on her hands and the blood on her dress. Later, when the cops ask to speak to Ethan, Chloe lets the police interview him without even insisting that he be represented by a lawyer. Nearly everyone Chloe knows in New York works either in publishing or the law. The dramatis personae is filled with Adam’s legal colleagues, and yet Chloe behaves as if she doesn’t know what a lawyer is.

What’s more, as portrayed in The Better Sister, the American legal system is even more irrational than Chloe’s behavior. As usual in TV dramas, the time between the arrest of a suspect and the start of the trial is ridiculously short. Ethan’s trial appears to begin just a few days after his arrest. The murder of Adam Taylor occurred in Suffolk County, Long Island. That’s also where the real-life murderer Rex Heuerman – known as the Gilgo Beach Serial Killer – was arrested. Heuerman was indicted in July of 2023 and yet his trial has yet to begin. Heuerman’s trial, which involves multiple charges of murder committed over many years, is undoubtedly more complicated than Ethan’s fictional trial. But Ethan comes from great wealth, and his family would probably have the wherewithal to delay his trial for a long time, hoping that witness memories would fade, exculpatory evidence might surface, and that the public would largely forget about the crime, making jurors less knowledgeable of the investigation. For some reason, however, Chloe wants her son tried as soon as possible, which seems like a really bad idea.

But even sillier is the way the actual trial is conducted. It is almost certain that Ethan’s lawyer would not allow him to testify in his own trial. Ethan is a troubled teenager, a bit of a loose cannon who frequently cosplays as an Arthurian knight, and no sane attorney would gamble that he would be able to stand up to intense cross-examination by the prosecutor. But what’s really nuts is that Ethan is called to testify by the prosecutor! He’s a prosecution witness – something that would never happen in real life. He is under no obligation to testify on behalf of the team trying to put him in jail. If he testified at all, he would be called as a defense witness by his own attorney. In that case, even though the prosecutor would be allowed to question him, he could only be asked questions related to matters that were raised during the defense attorney’s direct examination. But, in The Better Sisters, Ethan somehow ends up as a star witness for the prosecution. When the prosecutor shows Ethan some damning posts that he made in an online discussion group, Ethan confesses that he wrote the posts. He also confesses that he wanted his father dead. All this while his brain-dead defense attorney sits quietly in her chair and watches her case seemingly crumble before her eyes.

Also crazy is the testimony of Ethan’s best friend, a drug dealer named Kevin. Kevin originally helped the police poke holes in Ethan’s alibi for the time of the murder. Presumably he would make a great prosecution witness. But then Chloe corners Kevin one day while he is out selling drugs from his car and she orders him to say only nice things about Ethan when he testifies in court. This seems kind of bizarre. Kevin is a prosecution witness. Presumably he isn’t going to be asked anything by the prosecutor that will allow him to sing Ethan’s praises. But, sure enough, under questioning by the prosecutor, Kevin says nothing but nice things about Ethan. This is nuts. No doubt his cooperation in the trial was secured by threats to prosecute his drug dealing crimes unless he rats out Kevin. His testimony would have been heavily rehearsed. The prosecutor wouldn’t ask a question that he didn’t already know the answer to. But, somehow, when Kevin takes the stand, he simply talks about what a good and loyal friend Ethan is. Kevin notes that Ethan once took the blame for possessing some marijuana that actually belonged to Kevin. Why would the prosecutor sit and listen to all this nonsense? What kind of questions could have solicited it?

Also idiotic is the famous Perry Mason fallacy, in which every single witness expected to testify at the trial is allowed to sit in the courtroom and listen to the testimony of all the other witnesses. This, too, can’t happen in a real court of law. If the witnesses were allowed to listen to each other’s testimony, then they could alter their own testimony to keep it consistent with what the others have said. This would make it difficult to catch a witness in a lie. In The Better Sister, Chloe Taylor takes the stand and announces to the court that she and Jake Rodriguez, a coworker of Adam’s, were having an adulterous affair. She tells the jurors that Jake hated Adam, both because of his abusive behavior towards Chloe and because Jake wants Chloe all to himself. This gives Jake a motive for killing Adam and casts doubt on Ethan’s guilt. But Jake Rodriguez is sitting in the courtroom as Chloe makes these bombshell revelations. He wasn’t told that Chloe planned to make their secret romance public in her testimony. As soon as Chloe finishes testifying, Jake takes the stand and is questioned about the affair. Had he not listened to Chloe’s testimony, he would have denied having any sexual involvement with her. Now he is simply forced to plead the fifth over and over again.

Just about every second of the courtroom scenes is excruciatingly idiotic. If I didn’t enjoy looking at Jessica Beal and Elizabeth Banks and high-end New York real estate so much, I probably would have shut my TV off before the initial bail hearing had ended.

Several reviewers recently used the term “competence porn” to describe the pleasure of watching the MAX TV series The Pitt, a highly realistic drama about the medical experts who work in the trauma center of a busy Pittsburgh hospital. Even actual doctors, interviewed in the New York Times, praised the accuracy of the medical drama. Although I understood little of the medical lingo employed by the characters in The Pitt, and although I know nothing about how trauma medicine works, I believed to my core that the people who made this series understood exactly how trauma medicine works. And it was a great thrill to watch nurses, doctors, EMTs, and other medical professionals do their jobs with a very high level of competence and efficiency.

The legal professionals of The Better Sister demonstrated none of the competence on display in The Pitt. Even an idiot like myself could have outlawyered the dummies who passed for attorneys in The Better Sister. The prosecutor, for instance, berates the police investigating Adam’s murder for looking into suspects other than Ethan. Once Ethan has been arrested the prosecutor doesn’t want to give the impression that anyone else but Ethan might have had a motive to kill Adam. He tells the police to investigate no one but Adam. Naturally, the defense team is looking into all sorts of other suspects. And they find some good ones. And when they make the case in court that Jake Rodriguez had just as much motive to murder Adam as Ethan had, the prosecutor’s case falls apart. Had he looked into all potential suspects, the prosecutor might have been spared this embarrassment. The Better Sister succeeds as real-estate porn but fails as competence porn.

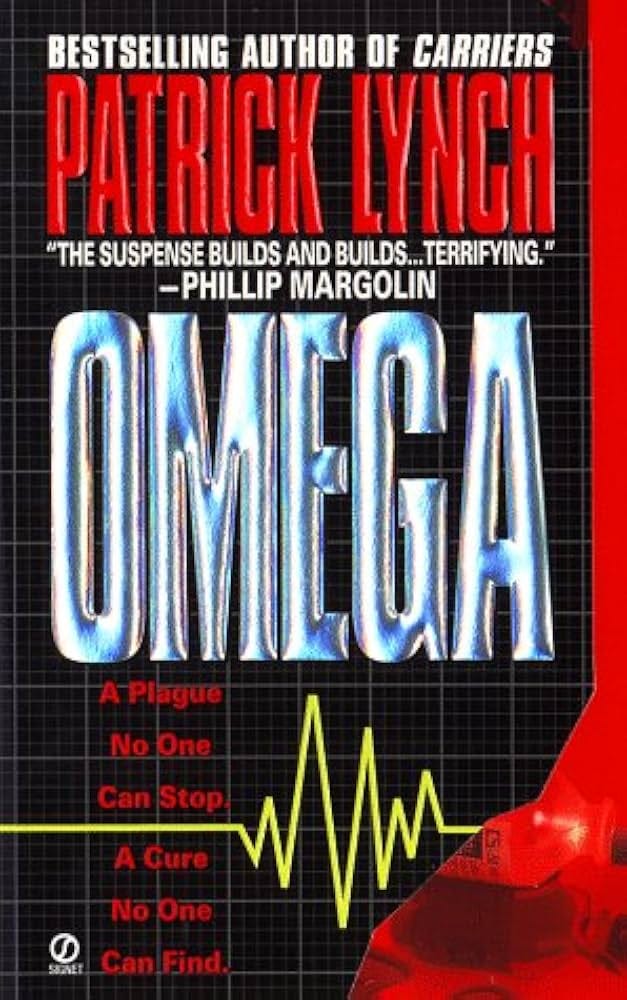

If you read the wrap-up of my 2024 reading year, you may recall that two of my favorite books last year were written by a Brit named Philip Sington. The best of these was his novel The Valley of Unknowing, published in 2012 under Sington’s own name. Nearly as good was Two Storm Wood, published in 2021 under the pseudonym Philip Gray. But I also read a medical thriller called Carriers, co-written by Philip Sington and Gary Humphreys, and published in 1995 under the joint pseudonym Patrick Lynch. Although I liked Carriers, I considered it almost fatally ambitious, loaded down with too many characters and incidents and too much globe-hopping travel, making it difficult to keep track of. As a result, though I knew that “Patrick Lynch” had published a handful of other thrillers, I didn’t bother seeking any of them out right away. Recently, however, I decided to read Omega, a medical thriller written by Lynch and published in 1997. I feared that this too might be another overly-stuffed thriller, but I was wrong. Omega was fairly tightly focused on a small group of characters and the action is set pretty much entirely in the Los Angeles area over the course of a couple of weeks. To my knowledge, neither Philip Sington nor Gary Humphreys is a medical professional, but the sophistication of the medical descriptions in Omega seemed to surpass even that found in the works of such doctors-turned-novelists as Tess Gerritsen, Robin Cook, and Michael Palmer. Sington and Humphreys clearly did their homework, but the novel didn’t feel like one of those fictions in which the author feels duty bound to insert every interesting factoid he uncovered during his research. The book contains a ton of information about bacterial infections and about antibiotics, but the authors do a good job of making most of this info accessible and interesting.

The basic premise of the book is that, by prescribing antibiotics to every patient who complains of a sore throat or a rash or a minor infection, doctors are actually weakening the human body’s ability to fight off bacterial infections. Antibiotics went into widespread medical use only in the late 1930s, about ten years after the discovery of penicillin in 1928. Before that, bacterial infections frequently claimed the lives of many weaker members of the population – children under five, very old people, and people with other co-morbidities. Antibiotics have been a godsend for humankind, but Dr. Marcus Ford, the protagonist of Omega is worried that the overuse of common antibiotics will eventually render many of them worthless. Bacteria have an ability to mutate and develop resistance to the antibiotics used against them. The more we use antibiotics, the better bacteria become at building up defenses to them. In a worse case scenario, we could find ourselves in a world without antibiotics again.

One character says to Dr. Ford (I’m paraphrasing): “But would that really be so apocalyptical? After all, antibiotics weren’t in use in the 1930s but those were hardly the dark ages. Plague and pestilence didn’t wipe out whole cities in the developed world. And sanitation and water treatment and germicide technology is a lot further along nowadays that it was in the 1930s. A lack of antibiotics might be harmful for people living in overcrowded third world countries, but how would it affect modern countries like the U.S.?”

Dr. Ford responds: “A lot. Because microbiologically the planet is now a world away from what it was in the 1930s. And because of the way that the world has opened up – with international trade and tourism, the ability to fly from one country to another – the whole system is permeable. Add to that the political instability and flows of refugees across national borders, and you have an unprecedented confusion of bacterial ecosystems. The whole thing about being able to rely on proper sanitation and urban planning goes out the window.” Scary stuff. And the book is full of such (disgusting) food for thought.

As the novel opens, the Willowbrook Medical Center in Los Angeles, where Marcus Ford works as a surgeon, has experienced several inexplicable deaths due to bacterial infection. Hospitals, unsurprisingly, are hotbeds of infection. Trauma centers and emergency rooms are especially prone to hosting infectious diseases because many of the patients brought to them are homeless and/or drug-addicted and/or mentally ill and have often not been taking good care of their health and probably haven’t been getting regular medical checkups. Often, by the time they show up at a hospital, their systems are teeming with bacteria and disease. As a result, some hospital patients pick up bacterial infections that they didn’t have before entering the hospital. These are called nosocomial infections.

As the infections continue to plague patients of Willowbrook Medical Center, the hospital’s upper management blames their outbreak on the doctors and other members of the medical staff. The managers believe that the surgeons, nurses, and so forth are not properly scrubbing up as often as necessary and have become vectors of disease and infection. The doctors are berated by their superiors and forced to undergo insulting treatments to determine whether they are the cause of the infections. But Dr. Marcus Ford believes that something else is causing the infections, something much more frightening. He believes that some new antibiotic-resistant bacteria are spreading among the more vulnerable populations of Los Angeles County. Willowbrook is located in South Central Los Angeles and serves mostly poor and minority members of the community. He believes that vulnerable members of the community are acquiring these bacterial infections outside the hospital and then bringing them into it when they are admitted. These bacteria are resistant to the most common antibiotics, which means that doctors must treat them with less and less common antibiotics, antibiotics that often carry large risks and dangerous side effects.

A medical thriller about a deadly and drug-resistant strain of bacteria spreading throughout the slums of Los Angeles would be scary enough. But Patrick Lynch has much more in store for his readers than a mere plague. When Dr. Ford’s 13-year-old daughter, Sunny, comes down with a mysterious bacterial infection that threatens to kill her, the search for the source of the bacteria becomes personal for Dr. Ford. Soon he discovers that a secretive group of medical researchers has actually come up with a powerful antibiotic called Omega (“the last word in antibiotics”) that can defeat any known bacterial infection, but the drug is being withheld from the public. The federal government, aware of Omega’s existence, has chosen to purchase the patent and stockpile the antibiotic in case of a nationwide (or worldwide) pandemic that threatens to topple the U.S. government. In other words, the drug is being reserved in case America’s rich and powerful should ever need it in order to survive a pandemic that threatens to kill America’s hoi polloi. The government would never approve using the antibiotic to treat poor black people in Los Angeles, because once a new antibiotic is introduced, it begins to lose his potency. If Omega is introduced into L.A.’s homeless community, it may, in ten years’ time, be worthless in helping the rich and powerful survive a plague.

Dr. Ford wants to make Omega available to the public in time to save Sunny. But nobody will officially acknowledge its existence. Several of the scientists who developed Omega, would also like to bring the drug to market. But, having sold the patent to another group, they are no longer allowed to mention Omega or produce any more quantities of it. And those who do mention it begin disappearing mysteriously.

Meanwhile, Dr. Ford, a widower, has been befriended by a beautiful young pharmaceutical sales rep who seems to share his zeal for finding an antibiotic that will save Sunny’s life. But is Helen Wray really on the level? Or is she secretly working to thwart Dr. Ford’s efforts to save not just Sunny but the at-risk population of Los Angeles?

The book combines fascinating (and presumably factual) details about the workings of both bacteria and antibiotics. One of the most interesting characters in the book is Dr. Lucy Patou, who is Willowbrook’s Chief of Infection Control. Her entire job is to keep infectious diseases from spreading throughout the hospital. She notes that the perineum (the strip of skin between a person’s anus and genitals, and commonly known by the slang term “taint”) is often the most bacteria-rich part of a human body (for obvious reasons) and she comes up with humiliating ways of determining whether Dr. Ford and his colleagues are properly washing theirs. She also forces each of the doctors to strip naked and sit in an isolation chamber for a half hour or so, while the air inside the chamber is checked for bacteria.

Though not written by doctors (to my knowledge) this book oozes with competence porn. Every medical fact at least sounded authoritative to me. What’s more, I frequently looked up some of the more bizarre facts mentioned in the book, Googling them and finding plenty of online sources that verified them. The book struck me as being at least as well researched as season one of The Pitt. Though it wasn’t quite as thrilling as Richard Preston’s The Cobra Event (published at roughly the same time as Omega and my gold standard for medical thrillers), Omega is one of the best of the genre. Curiously, it bears a lot of similarities to Robin Cook’s novel Toxin, which was published in January of 1998, just a few months after Omega, which was published in hardback in September of 1997. Both books feature an unmarried doctor whose teenage daughter comes down with a life-threatening illness as a result of a meal eaten at a fast-food joint. Both doctors find their medical privileges revoked by their hospitals because of the extreme lengths they are willing to go to in order to save their daughters. But Cook’s novel devolves into an action thriller at about the midpoint, after which medicine takes a back seat to fistfights and gunplay and such. Fistfights and gunplay also enter into Omega, but much later in the novel and they never overwhelm the medical dramas at the heart of the book.

In Omega, Patrick Lynch demonstrates how to do competence porn right. In The Other Sister, Amazon Prime demonstrates how to do it wrong. The miniseries has its virtues, but providing us with a glimpse of publishing and/or legal professionals performing at the peak of their powers isn’t one of them. Fortunately, Corey Stoll, Kim Dickens, Jessica Biel, Elizabeth Banks, and Matthew Modine are still at the height of their professional competence, and watching them, even in this uneven production, is great fun. In the meantime, Amazon (or some other streaming service) ought to consider turning Omega into a miniseries. Perhaps the success of The Pitt will make that more likely to happen.