THE AMERICAN CITY SAGA

During the last three decades of the twentieth century a pop-fiction genre arose that has never been given a proper appraisal, or even a name. I’m talking about books, most of them written by women, that chronicled the rise of an American city, usually as seen through the eyes of a single family or, in some cases, a single (long-lived) individual. Examples of the genre include Charleston and Leaving Charleston by Alexandra Ripley (one of the genre’s grandes dames), New Orleans Legacy, also by Ripley, Seattle by Charlotte Paul, Palm Springs by Trina Mascott, Crescent City (one of New Orleans’ many aliases) by Belva Plain, Hers the Kingdom (which dramatized the early years of Malibu, CA) by Shirley Streshinsky, That Wilder Woman (also about Malibu) by Bruce Jay Kaplan, Biscayne (about Miami, FL) also by Kaplan, Days of Valor (which dramatized the rise of Knights Ferry, once the hub of Stanislaus County, CA) by Willo Davis Roberts, Paloverde (which chronicles the rise of L.A.’s mercantile, oil, and filmmaking sectors through the eyes of three generations of the fictional Van Vliet family) by Jaqueline Briskin, Vintage (about Napa, CA) by Anita Clay Kornfield, Natchez by Pamela Jekel, Savannah (and its three sequels) by Eugenia Price, Maria (a novel about St. Augustine, FL, which spawned two sequels) also by Eugenia Price, Galveston by Suzanne Morris, The Immigrants (a novel about San Francisco, which spawned five sequels) by Howard Fast, Mendocino by Judith Greber, and Cape Cod (rather than a city, it covers a region conterminous with Barnstable County, MA, but still in the ballpark) by William Martin. All of these books were published between the mid 1970s and the mid 1990s.

This genre – which, for the sake of convenience, I’ll call the American city saga – probably owes much of its viability to the success of James Michener’s massive historical sagas of place, the first of which, Hawaii, appeared in 1959. But whereas Michener’s tomes generally cover a vast subject – Texas, Alaska, the Caribbean, Poland, Space, etc. – and often stretch thousands, or even millions of years into the past, city sagas tend to be much more tightly focused and compact. Sometimes these sagas cover just one important epoch in the history of a city. Crescent City, for instance, covers the years just before, during, and just after the Civil War. Palm Springs, on the other hand, begins in 1912, 26 years before the city was incorporated, and ends in 1987, a span of years that saw the area grow from a destination mainly for TB sufferers seeking dry desert air to its current status as a playground for the rich and famous. Of course, there are city sagas that follow the Michener playbook. Edward Rutherford’s 2010 novel, New York, covers three centuries and is nearly 900 pages long. But the novels published during the heyday of the genre (1975-1995) tend to eschew Micheneresque magnitude and embrace a more personal esthetic (the story of Palm Springs is told mainly through the eyes of its main character, Ginger McKinntock, who is brought to the town in 1912 as a child and grows up with it).

In the late 1980s, Signet books brought out a series of novels called Fortunes West, each of which chronicled the rise of a city in the American west: San Francisco, Salt Lake City, Cheyenne, and Tucson. The books were all credited to A.R. Riefe, an author I can find no information about and suspect was a publishing house pseudonym. The books are generally dull and lacking in style, suggesting they were written by a committee of researchers and low-level literary talents. The series seems to have been modeled after the more successful Wagons West series, published in the 1970s and 1980s to capitalize on the renewed interest in American History which the country’s bicentennial celebration inspired. Credited to Dana Ross Fuller (a pseudonym for James Reasoner and Noel B. Gerson), most of these books featured the name of an American state followed by an exclamation mark (Oregon!, Utah!, Nebraska!, etc.). They also bear some resemblance to John Jakes’ various bicentennial-inspired historical-novel series, such as the Kent Family Chronicles, and the Crown Family Saga. Your mileage may differ, but I find the novels in series such as Wagons West and Fortunes West, which were clearly dreamed up in some publishing company’s marketing department, to be far less interesting than those stand-alone novels that are clearly works of passion by authors with a personal connection to the places they are chronicling. Trina Mascott is a long-time resident of Palm Springs, and her attachment to the city comes through in her novel about the city. Alexandra Ripley was born in Charleston, South Carolina, and her love for the city can be found not only in her novel Charleston, but even in Scarlett, the sequel to Gone With the Wind that she was hired to write by the heirs of Margaret Mitchell. Galveston, by Suzanne Morris, is clearly a passion project written by a woman with a deep interest in Texas history. So too are her novels Wives and Mistresses (which chronicles the growth of Houston) and Keeping Secrets (San Antonio).

And then there are the authors who produce novels that sound as if they will be about the birth and rise of an American city but end up being about something else entirely. Gore Vidal wrote novels called Hollywood, Duluth, and Washington, D.C. but none was about the rise of an American city. Vidal was obsessed with American politics. Washington, D.C., covers the American political scene between the years 1937-1956. Despite its title, roughly two thirds of Hollywood is also set in Washington, D.C. And as for Duluth, well, the less said, the better (the Duluth of the title, which is located near the Mexican border, bears no resemblance to the Duluth of Iowa). Pat Booth, a model-turned-photographer-turned-fiction-writer, churned out a slew of novels in the 1980s and 1990s with titles like Big Apple, Beverly Hills, Malibu, Palm Beach, Miami, and Nashville. Alas, these were not sprawling historical epics but contemporary sex-and-shopping novels about the rich and famous residents of America’s most storied cities. Likewise, in the 1970s, Burt Hirschfeld, a hack of all trades whose specialty was the TV and film novelization (Kelly’s Heroes, Bonny & Clyde, etc.) cranked out titles such as Aspen, Provincetown, Acapulco, and Key West. These were sex-and-shopping novels without much shopping. Hirschfeld’s jet-setting millionaires spent their days figuratively screwing each other in the boardroom and their nights literally screwing each other in the bedroom. It’s easy to understand why, when the TV series Dallas became a pop-cultural phenomenon in the late 70s and early 80s, Hirschfeld was tapped to write the series of Dallas novels that Bantam Books rushed into print in order to capitalize on the phenomenon.

Fans of the American city saga know not to judge a book by its title. Chris Abani’s 2014 book, The Secret History of Las Vegas: A Novel, is, in fact, not a city saga but rather a crime novel that unfolds over a relatively short span of time and spends nearly as much of that time in South Africa as it does in Vegas. John Dunning’s 1980 novel, Denver, is focused rather tightly on the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in that city during the Roaring Twenties. Geoffrey Wolff’s Providence is a good crime novel set in Rhode Island’s capital city, but it won’t tell you much about the birth and rise of that city. William Kennedy’s three-novel Albany Cycle may be good literature but it isn’t a city saga as I define the term.

City sagas generally have enough going on in their multifarious narratives that fans of just about any literary genre – romance, history, adventure, war, westerns, etc. – can probably find something to enjoy in the genre’s best examples. I first wrote this essay for the editor of Ellery Queens Mystery Magazine, which is why it focuses especially on city sagas that are somewhat adjacent to the mystery/crime genre. While not all city sagas contain elements of the mystery novel or the crime novel within their pages, there are some noteworthy exceptions.

Don’t be fooled by the title of Clint McCullough’s 1986 novel, Nevada. This isn’t a vast historical epic that covers the entire history of America’s 36thstate, from the era when it was populated mostly by the Paiute, Washoe, and Shoshone Indian tribes, through the years when it was a part of the Viceroyalty of Spain, and then on to its role in the Mexican-American War and its years as a part of the Utah Territory. A better title for this novel might have been A Tale of Two Cities, because the book mainly focuses on the rise of the gaming industry in both Reno and Las Vegas between the years 1920 and 1986. Some attention is also paid to Nevada’s third gambling hub, the Stateline/Lake Tahoe area, but that seems more of an afterthought. The vast majority of the book focuses on Reno and Las Vegas. And it doesn’t take much knowledge of history to realize that a story about the rise of the Nevada gaming industry is also going to be a story about organized crime. This novel is chock full of mobsters, hit men, protection rackets, and shady business deals. Had it been published in 1969, it might have rivaled The Godfather as the most popular mob novel of the years.

Nevada tells of the rise of the state’s gaming industry primarily through the life story of Meade Slaughter, a fictional casino magnate who appears to have been at least partially based on real-life casino magnate Bill Harrah. Harrah (1911-1978) was an honest man who managed to thrive in a largely corrupt industry. He was instrumental in the founding of Nevada’s Gaming Control Board in the 1950s, which eventually helped eradicate much of the industry’s corruption and its ties to organized crime. Like Harrah, the fictional Meade Slaughter starts out running carnival-style betting games in southern California. This was a tough way to make a living. Meade Slaughter’s early life is hard and peripatetic. He roams all across America, running carnival games at various amusement parks – Belmont Park in San Diego, Riverview Park in Chicago, Panama City Park in Miami, Playland in Rye, New York. He basically just leases space from these facilities, so the profits are mostly all his. He gets married, has a son, and begins investing heavily on the New York Stock Exchange in order to build a secure future for his family. Alas, this is in the Roaring Twenties, and a huge stock-market crash awaits at the end of the decade.

After being wiped out by the crash, Meade must start again. He falters for a few years, but on March 19, 1931, Nevada Governor Fred Balzar signed a bill legalizing pretty much all forms of gambling throughout the state (this was an emergency measure, since the Depression and the petering out of Nevada’s silver mining industry had thrust the state into financial ruin). The rest of the country wasn’t pleased with this development. McCullough writes:

The act brought down a torrent of abuse from newspapers across the country. “Cancel Nevada’s statehood,” cried the Chicago Tribune. The Dallas News and the Los Angeles Times called Nevada “a vicious Babylon.” An eastern paper cracked, “If you can’t do it at home, go to Nevada.”

At about the same time, Nevada also legalized divorce and authorized its courts to grant one to any petitioner who had been a resident of the state for at least three months. This brought in a steady stream of new temporary residents, who would settle into rented rooms and wait out the three-month period while also, the state hoped, spending lots of money at various shops and grocery stores and restaurants and gambling casinos. When other states began offering divorces to anyone who resided in state for three months, Nevada cut its residency period to six weeks. And thus Reno became, almost overnight, the nation’s capital of both gambling and divorce. This freewheeling attitude towards vice attracted a lot gambling entrepreneurs to Nevada in the 1930s, men such as the fictional Meade Slaughter and the very real Bill Harrah. Alas, by this time the Great Depression as well as the itinerant life of a carny man’s wife has taken its toll on Meade Slaughter’s wife, Shirley. Alcoholism eventually claims her life. Heartbroken, Meade places his son, David, in the care of a loving and prosperous family and devotes himself fully to his gaming parlor, called The Plush Wheel. Slaughter starts out small, with a single downtown Reno location. But his natural talent for business and marketing soon turn The Plush Wheel into a huge success, making Slaughter a threat to the primacy of Carlo Giuliano, the Reno casino industry’s top dog and a man with plenty of mob connections. While researching an up and coming gambling Mecca four hundred and forty miles south of Reno, a little desert town called Las Vegas, Slaughter falls in love again, with a young woman named Sandra. Alas, as Meade and Sandra begin planning their wedding, Carlo Giuliano decides he’s tired of competing with Meade and sends out two thugs to kill him. The thugs attack Meade just as he’s leaving his Reno casino late one night. Meade doesn’t know that Sandra is sitting nearby in a parked car, hoping to surprise him after his long day at work. When she sees Giuliano’s thugs attack Meade, she leaves the car and runs to his rescue. Taken by surprise, the thugs crack her skull with a bat and then leave them both for dead. But only Sandra dies. Meade is rendered paralyzed and is taken to San Francisco, a city with much better hospitals than Reno. Through an agent friend of his, Meade sells off The Plush Wheel for $100,000 (a grand sum in the depths of the Depression), retaining ownership of nothing but the name (the new owner is forced to rename it). Meade uses part of the money to set himself up in a seaside cabin with a few loyal aides and becomes determined to regain the use of his legs. He hires a local carpenter, Tom Bailey, to rig up a system of pulleys and handrails to help him learn to navigate his cabin, using mainly the strength of his arms. A specialist in spinal injuries checks in on Meade every week. Over the course of the next two years, Meade very slowly begins to regain the use of his legs, but he keeps this news from the doctor and makes his aides swear to keep it a secret. Eventually he is able to go outside at night and wander across the sand dunes for miles and miles. But as far as the local medical community is concerned, he remains a paraplegic. At first I found myself wondering why Slaughter didn’t want his ability to walk to become common knowledge. But, like any crime fiction fan, I was soon able to figure out Slaughter’s plan. In the summer of 1938, a now fully recovered Meade Slaughter drives from San Francisco to Reno with his lifelong buddy, Smitty. He spends a few days living in Smitty’s cabin in the Nevada desert outside Reno, where he mostly practices firing a shotgun. In the dead of night, on August 10, the second anniversary of Sandra’s murder, Meade waits outside of Carlo Giuliano’s headquarters. Eventually he sees Giuliano and his chief of security, Doug Clausen (the thug who killed Sandra), emerge from the building. Meade has set up a perfect murder. All he has to do is unload one barrel full of shotgun shells into each of his two enemies and then return to San Francisco. No one would ever suspect a bedridden San Francisco invalid of carrying out a murder two hundred and twenty miles away in Reno, Nevada. But does Meade’s plan work the way he wants it to? You’ll have to read the book to find out. And in case you’re worried that I’ve given away the climax of the book, relax. The novel is 640 pages long and everything I’ve mentioned takes place in the first 125 pages. The rest of the book contains a lot more criminal activity, much of it nonfiction. The rise and fall of Bugsy Siegel is chronicled here. Likewise the bloody demise of real-life mobster and casino operator Gus Greenbaum, who became manager of the Flamingo in Las Vegas after Siegel’s untimely departure. Real-life mobsters Moe Sedway and Meyer Lansky also put in appearances. (Fun fact, the fictional mobster Moe Greene, who appears in Mario Puzo’s novel The Godfather and was played by Alex Rocco in Frances Ford Coppola’s film version of the book, was based on Bugsy Siegel but his name is a composite of Moe Sedway and Gus Greenbaum. In his twenties, Rocco himself was a member of The Winter Hill Gang, an organized crime family in Boston, MA).

Clint McCullough’s Nevada is a good choice if you want a lot of crime and action. I enjoyed it a great deal. The downside of the novel, however, is McCullough’s prose. Generally it is workmanlike and efficient, sort of like the writing of a decent newspaper columnist – nothing spectacular, but it does the job. McCullough’s prose is marked by just a couple of serious flaws. He leans heavily on clichéd phrases:

Mario Gatori knew on which side his bread was buttered.

Marriage seemed like the icing on the cake.

Didn’t give us the chance of a snowball in hell!

We’re not going to cut off our noses to spite our faces!

On page 497 McCullough writes: Reese came through [the investigations] with flying colors.

On page 506 he writes: “With the passing of time, and as Reese passed every test with flying colors…”

I’m not as squeamish about clichés as some literary purists are. After all, plenty of people (myself included) use them frequently in everyday speech, so their appearance in a work of fiction isn’t entirely unwarranted. But even by the lax standards of American mass-market fiction, McCullough’s heavy reliance on clichés is glaring and can get tiresome.

His second weakness is more technical and it may not bother you. The writing guidebooks refer to this flaw as “describing consecutive actions as though they were concurrent.” Here’s an example from Nevada:

Tossing off her dress and putting on a garter belt, Gari sat at the edge of the bed and pulled a nylon up over one leg.

All McCullough had to do to correct this mistake is write, “After tossing off her dress and putting on a garter belt…” But the way he phrases it, Gari seems to be tossing off a dress and putting on a garter belt at the same time as she sits on the bed and pulls up a nylon stocking. Gari’s a talented entertainer but not quite that dexterous.

Elsewhere he writes:

Changing, Reese went down to the casino.

Most likely, Reese did the changing in his hotel room and then went down to the casino, but McCullough describes it as though he did both these things at the same time. These little tics, which occur throughout the book, bother me, but you might not mind them. And, despite these flaws in the prose, the story is still great fun to read.

Las Vegas, Nevada, and Palm Springs, California, have a lot in common. Located about 280 miles apart, each is a high desert community situated in a valley ringed by tall mountain ranges. Neither city is very old. Palm Springs wasn’t incorporated until 1938. Las Vegas was incorporated in 1911 but remained pretty much a whistle-stop for the Union Pacific Railroad until the state of Nevada legalized gambling in the 1930s. Both cities draw plenty of celebrity visitors from the film and music industries of southern California. And so many celebrities have made their homes in these cities that Wikipedia keeps separate pages listing each city’s Notable Residents. Both cities are noted for their mid-century modern architecture. Although not as notorious for its mob links as Las Vegas, Palm Springs has been home to plenty of crime figures. Chicago crime bosses Tony “Big Tuna” Accardo and Joey “The Dove” Aiuppa both had homes there. Los Angeles Mafiosi Jimmy Caci and Michael Rizzitello also maintained residences there. Caci operated loan sharking operations in both Las Vegas and Palm Springs. Jackie “The Lackey” Cerone, James “The Turk” Torello, Frank “The Horse” Buccieri – the Coachella Valley, where Palm Springs is located, has housed many a made man with a colorful nickname. Frank Sinatra had a home in Palm Springs and plenty of connections to Las Vegas, where he was a frequent performer (he was also the only actual entertainer to attend the notorious Havana Conference, a 1946 meeting of America’s top mob bosses where the execution of Bugsy Siegel was first proposed – a meeting depicted in Clint McCullough’s Nevada).

Trina Mascott’s 1990 novel Palm Springs mostly avoids mentioning the city’s mob connections. But that doesn’t mean it eschews the topic of crime entirely. Though not as crime-ridden as Nevada, Palm Springs has enough misbehavior in it to satisfy both fans of the historical novel and fans of the crime novel. Ginger McKinntock, born in 1900, comes to Palm Springs from San Francisco in 1912. Her mother has just died and her father, largely broke, moves to the Coachella Valley because his late wife had inherited some acreage there. Ginger quickly falls in love with Palm Springs. Alas, her father quickly falls in love with a divorcee on the prowl and, after marrying her, moves with her to Pasadena. Unlike her two siblings – sister Ella and brother Neil – Ginger loathes Pasadena and longs to return to the desert. Eventually she will return to Palm Springs. Her family cuts her off financially, but she doesn’t care. She goes to work at the Desert Inn (an actual Palm Springs resort that operated between 1909 and 1967) and gets an education in the hospitality business from the Inn’s owner Nellie N. Coffman, a real-life historical figure. Ginger falls in love with, and eventually marries, Tonito Alvarez, a Harvard-educated lawyer and a member of the local Agua Caliente Indian tribe. They have two children, Johnny and Tony, and live happily on a small homestead until a flash flood comes along and kills both Tonito and his oldest son, Johnny. Ginger goes back to work at the Desert Inn. Local doctor Avery Rowland, who has been in love with Ginger since she first arrived in Palm Springs as a 12-year-old girl, has kept his love for her a secret because he is married (to a consumptive) and because he is fifteen years her senior. Nonetheless, he looks out for her and for little Tony. As the years go by, Ginger will become a prominent hotelier in Palm Springs. Her sister Ella will become a famous film star as well as a promiscuous husband-stealer. Brother Neil will become a filthy rich but extremely sleazy businessman (most of his money is made by erecting cheaply made houses on beautiful tracts of Palm Springs land inherited from his father). Lots of cocaine and other drugs will be bought, sold, and abused. Lots of kinky (with the emphasis on “kin”) sex will be detailed. The book is filled with startling revelations. For ten years or so after Tonito’s death, Ginger refuses to even consider another romantic relationship, out of devotion to his memory. But eventually she will learn a shocking secret about Tonito that tarnishes him in her eyes and allows her to restart her love life. The book spans the years 1912 to 1987. One major character will be involved in a heart-stopping escape from the Nazis in occupied France. Two major characters, vacationing south of the border, will die in the notorious Tlatelolco massacre, wherein hundreds of unarmed Mexican student protesters were killed by Mexican Armed Forces (who received intelligence information from the CIA and weapons and ammunition from the Pentagon) ten days before the start of the Mexico City Olympics. One major character will intentionally crash his private plane into the San Jacinto Mountains. But the part of the book that crime fans will find most intriguing comes in the second half of the novel when one of the characters decides to have the wealthy girlfriend he lives with kidnapped by associates of his. He is a kept man but is rarely given much money to spend. His associates will grab his girlfriend and hold her in a remote cabin in the Coachella Valley. They will send the mastermind of this plot a ransom note but, with no money of his own, he’ll turn to his girlfriend’s wealthy family for the ransom money, assuring them that she will reimburse them after her safe return. Once he has the money, he and his two associates will divvy it up. The girlfriend will be released and reimburse her family. The mastermind will now have a large nest egg of his own, and nobody will be any the wiser. As you might expect, the plan goes awry. Soon a murder ensues and enough complications arise to satisfy most avid crime-fiction lovers.

But even when the characters in Palm Springs aren’t hatching kidnap plans, the story twists and turns like a thriller. The characters are constantly plotting to destroy each other’s marriages, or careers, or happiness. Through it all, Ginger remains a beacon of rectitude (well, at least in comparison with Nevada’s Meade Slaughter), and Doctor Rowland remains wholeheartedly in love with her. And in the end, Ginger has become as much of a towering figure in her adopted hometown of Palm Springs as Meade Slaughter is in his adopted hometown of Las Vegas. Because, the two novels cover similar time periods, and unfold in similar desert locales, and were published within five years of each other, they feel like companion pieces. Both novels contain a lot of real-estate battles, incestuous relationships, and violent deaths. I recommend reading them back-to-back. Think of them as a Dynamic Duo of the Desert.

Palm Springs is generally well written, except when it comes to sex. Mascott, who turned 100 in the summer of 2020, was 70 when Palm Springs was published. A person born in 1920 didn’t grow up reading many graphic sex scenes in popular novels. The vogue for that kind of thing didn’t really explode until the arrival of Harold Robbins and Jacqueline Susann in the late 1960s. I think it is admirable that a writer of Mascott’s generation made an effort to give her novel the kind of frank sex scenes that were a hallmark of pop fiction in the late 20thCentury. Alas, she is pretty awful at it. Here’s an example:

She could be a purple-assed orangutan for all he cared. All he wanted was to shove his penis into her bloated body and find total bliss.

Here’s another:

She longed to be back in his arms. When she imagined kissing him again, she felt as though a miniature elevator were swiftly rising and falling between her groin and her throat, leaving a path of dizzying desire in its wake.

And one more:

A sexual thrill grabbed his groin and spread throughout his body.

If that strikes you as fine writing, then Palm Springs will no doubt dazzle you with its eloquence. Alas, I find those passages laughably awful. Curiously, Mascott actually writes well when she isn’t writing about sex. Her evocations of the Coachella Valley and its dessert landscapes are beautiful. Her description of a deadly flash flood is brilliantly rendered. She writes well about almost everything – except sex. Alas, there is quite a bit of sex in Palm Springs (both the book and, I imagine, the city), so prepare yourself for a lot of ludicrously purple prose (or purple-assed prose). Other than this flaw, I really enjoyed Palm Springs, more so even than I did Nevada.

Galveston, by Suzanne Morris, begins on March 1, 1877, and ends on December 26, 1920. Its nearly 500 pages are broken into three sections, each one narrated by a different female character. All three narrators are related by blood to each other, although their kinship is somewhat tangled and mysterious. Each of the three sections could almost serve as a stand-alone novel. The first section is narrated by Claire Becker, a young woman who finds herself pregnant after a few secretive trysts with a scoundrel named Damon Becker. Damon has left town, and isn’t the marrying type anyway, so Claire connives to marry his less exciting brother Charles, a young attorney who has long pined for her, and then convince him that the child she is bearing belongs to him. The plan works but the marriage eventually leaves both Claire and Charles restless and unsatisfied. For much of its length this first section reads like an Anne Tyler novel about a dysfunctional marriage. But it concludes with a shocking crime that seems more like a twist from a well-wrought gothic romance.

Section two is narrated by 19-year-old Serena Garret. Young enough to be Claire’s daughter, she lives next door to the Beckers with her preacher father, Rubin, and his sickly, artistic wife, Janet. A summer romance with an itinerant musician named Roman Cruz results in a pregnancy for Serena. Her closest confidant is a neighbor boy named James, who helps her keep her assignations with Roman a secret. Serena and James don’t know it, but they are brother and sister. By the end of this section, Serena and Roman are planning to run off to New York to be married and start their lives anew. Section two reads like a literary coming-of-age novel but it lacks a resolution. That comes later.

The final section is narrated by Willa Frazier, the adopted daughter of Houston millionaire Bernard Frazier and his wife, Edwynna. On the eve of her wedding to up-and-coming Houston Realtor Rodney Younger, Willa discovers a clue to the identity of her birth mother and then abandons her wedding plans to go off in search of the mother she never knew. This section plays out like a true mystery, with an amateur sleuth who uncovers clues, follows them, and then investigates various players in the mystery surrounding her conception, birth, and adoption. Near the end we get a scene very reminiscent of the conclusions of Agatha Christie novels featuring Hercule Poirot or Miss Marple. It’s the drawing-room scene where the detective explains how the murder was committed. In Galveston, the explanation runs for more than fifteen pages and contains decades worth of lurid incidents, including murder, suicide, extramarital affairs, unwanted pregnancies, secret adoptions, arson, a missing diary, and even the poisoning of a beloved dog. And even after all of that, the mystery isn’t completely solved. Willa and her informant must travel back to Galveston before they can tie up all the loose ends and find out what really happened to Willa’s birth mother. And through it all we learn of various fascinating episodes in the history of Galveston, including the fire that destroyed a beloved beach resort and the mega-hurricaine of 1900, which killed more than 6,000 Galveston residents and remains the deadliest weather event in the history of the United States.

It seems likely that Galveston was inspired, at least in part, by Willa Cather’s Pioneers!, which concerns itself mostly with the familial and romantic relationships of various small-town Americans near the turn of the 20th century until it erupts into horrific violence near the end.

Cape Cod, by William Martin, be the most ambitious of all the books under discussion here. The story begins in 1000 A.D. and concludes in the 1980s. The front pages of the novel contain maps and several helpful family trees. One thread of Martin’s story concerns itself with what may be the very first murder in American history, the death of Dorothy Bradford, 23, a real-life pilgrim who came to America aboard the Mayflower, in 1620, and died mysteriously in November of that year, possibly as the result of foul play (or suicide, or a tragic accident). Her husband, William Bradford, who eventually became governor of the Plymouth Colony, never mentioned her death in the journal he kept, which strikes some historians as suspicious. At any rate, poor Dorothy Bradford’s death is only one of the mysteries set forth in this massive novel. The main focus of the book is the ongoing, centuries-old feud between the Bigelow and Hilyard clans, two Cape Cod families that can trace their lineage directly back to the Mayflower. Another important plot thread concerns the search for the long-lost log of the Mayflower’s master, Captain Christopher Jones.

In some ways this book stretches the definition of the American city saga since, as mentioned above, it covers an entire county. But Barnstable County, Massachusetts, isn’t huge. Even today the population is under 250,000 (a number which, like the temperature, swells during the summer months) and the county comprises only about 544 square miles. My home county, Sacramento, CA, covers nearly twice that. The city of Los Angeles covers 502 square miles, and don’t even get me started on the city of Sitka, Alaska, which covers nearly 5,000 square miles and has inspired a city saga of its own, Sitka, by Louis L’Amour. Although an early introductory chapter of Cape Cod takes place in 1000 A.D., the story proper begins with the arrival of the Mayflower in 1620. And though the narrative covers more than three centuries, it does so while focusing tightly on the members of just two families. Thus, Cape Cod seems closer in spirit to city sagas such as Palm Springs and Galveston than geographical doorstops such as James Michener’s Chesapeake and Centennial. If you like both history and mystery, give it a go.

Barry Jay Kaplan is a good writer. His novels Black Orchid (co-written with Nicholas Meyer) and Biscayne are both highly entertaining, but That Wilder Woman (1985) is my favorite of his books. It is a fictionalized account of how Frederick Rindge and his wife, May, acquired the land now known as Malibu, CA, in the late 1800s and fought for decades to see that it remained largely an unspoiled wilderness area. Most of that fight was waged by May alone, for Frederick died young in 1905. In Kaplan’s novel the Rindges are called Emmett and Ada Newcomb.

Ada is the star of this story. She grows up in tiny Desideer, MI, a dreary farming community. Her father abandoned the family when Ada and her younger brother, Obadiah (Obie), were young. Her mother became mentally unstable after that and died a few years later. It was up to Ada to raise her brother and run the household. When Ada’s own schooling ended, she took over the running of the town’s one-room schoolhouse. But she wanted nothing more than to escape dreary Desideer and lead a more adventurous life. Alas, she lacks the wherewithal to pursue this dream. Fortunately, her hometown boasts one genuine celebrity, a female photographer whose work is famous nationwide. A photograph of Ada taken by this photographer somehow manages to appear in a Boston newspaper, where it catches the eye of young Emmett Newcomb, scion of a wealthy family. For health reasons (bad lungs), his doctors have recommended that he move to southern California, preferably somewhere along the coast. Inspired by Ada’s photo, he decides to take a short detour on the way to California and stop in Desideer, where he asks Ada to marry him and join him on his great adventure. So anxious is Ada to escape that she doesn’t bother playing hard to get for very long. After a courtship of only a few days, Ada agrees to marry Emmett on one condition: after they are settled in California, Emmett must allow her to send for Obie to join them out west. Emmett has no objection to this condition, so off they go.

Alas, young Obie sees Ada’s marriage and departure as the worst of the three abandonments that have defined his life (his father ran off and his mother died young). Angry, he decides not to wait for Ada to send for him. He steals a gun and a horse and heads west. He plans to work his way west by hiring himself out as a cowboy along the way. But his psyche has become warped by all the hardship he has seen, and soon he becomes a murderous psychopath, killing primarily prostitutes (upon whom he is no doubt taking out the anger he feels towards Ada, on whom he has a dangerous and incestuous fixation). His trek west is interrupted by various crime sprees and long stretches in jail. The famous photographer from Desideer writes to Ada and lets her know that Obie left town a wanted man. After that, Ada loses track of him for years.

In California, Emmett finds his Shangri-La, a 13,500-acre ranch located upon the Pacific Ocean just west of Los Angeles. Back then the ranch was known as The Malibu, from a Chumash Indian word meaning “place of loud surf.” He uses his $200,000 inheritance to buy the place and then he and Ada set about establishing a working cattle ranch on part of the land. The rest he hopes to leave relatively undisturbed. Sadly, various southern California business interests find it inconvenient having a large track of undeveloped land lying just north of Los Angeles. The Southern Pacific Railroad wants to run a rail line through the property. The state highway commission wants to run a highway through it. Various L.A. merchants want to establish a large shipping port along the coast of The Malibu. And the owners of smaller ranches adjacent to The Malibu want easements over the property so they can water their stock and move them to market. The Newcombs (like the real-life Rindges) find themselves besieged by eminent domain lawsuits, class-action lawsuits, angry neighbors, opportunistic politicians, and even cattle rustlers. On top of all that are the wildfires that (even to this day) plague the area.

So here you have all the elements of a great two-pronged saga. While Ada fights off various legal and natural threats to The Malibu, she is unaware of what is potentially the biggest threat of all – the psychopathic brother she’s lost track of and who, like an avenging angel, is slowly but inexorably moving west, determined to have his revenge against the sister whom he believes is the source of all his troubles in life.

Obie bears a resemblance to the crazed protagonist of Cormac McCarthy’s novel Child of God. Ada’s portrait, on the other hand, owes much to an even more famous literary forbear. Her determination to save The Malibu calls to mind Scarlett O’Hara’s efforts to save Tara. So, is That Wilder Woman the equal of either of those two classics? Alas, no. But give Kaplan his due. For a relatively short novel (258 pages), That Wilder Woman manages, for most of its length, to feel like a genuine historical saga. It packs a bigger wallop than many far longer California historical novels. And though it is fictional it gives the reader a reasonable overview of how a large tract of land that once belonged to the Chumash Indians went from being a largely unspoiled wilderness area to one of the most expensive zip codes in the country.

Shirley Streshinsky’s 1981 novel, Hers the Kingdom, is an even better fictionalization of the Rindge’s story but, though it contains rape and murder and other crimes, it doesn’t give off the same kind of thriller vibe as Kaplan’s book. Barbara Wood’s 2002 novel Sacred Ground gives Malibu the Michener treatment, unspooling a fictionalized history of the region that stretches from roughly the year 1 A.D. to the year 2000. Only Kaplan seems to have been writing for lovers of Westerns and crime novels.

But Kaplan’s book ends just as Hollywood’s Silent Movie era is beginning. It leaves us guessing as to what would come next. For the answer to that question, you might want to grab hold of Pamela Wallace’s Malibu Colony, published in 1980. It begins in 1922 and concludes in 1979. Like Suzanne Morris’s novel Galveston, Malibu Colony is broken into three separate novella-like sections. The first concerns itself with Maggie Jones, a girl who, in the book’s opening pages, escapes from a broken home in Fresno and makes her way to Hollywood, arriving on her 18th birthday, September 22, 1922. She looks in the want ads of the L.A. Times and finds an ad placed by one Lyla Moran, an aspiring actress who is seeking a roommate to share the expenses of the bungalow she is renting. Maggie answers the ad. The two women hit it off right away. Thus, on her very first day in Hollywood, Maggie finds herself accompanying Lyla to a party at the fabulous Beverly Hills estate of Wally Gordon, a famous (fictional) star of the silent screen. While she is walking through the backyard of Gordon’s massive estate, Maggie witnesses a murder. A prostitute is shot dead by a wealthy young man she had been sleeping with and providing with illegal drugs. Presumably she was trying to blackmail him (she has a history of doing this) when he took offense and killed her. The young man is the son of Sam Lendt, co-owner of American Universal Pictures, a major film studio. Sam’s partner Ben Montgomery, shows up at the party to handle damage control. The dead girl’s body is dumped in the ocean and the police are bribed to overlook the bullet hole in her chest and say that she drowned. Lendt’s son is whisked away to a sanitarium. And, because she witnessed the shooting and can’t easily be disappeared herself, Maggie is offered a screen test with American Universal in exchange for her silence about what she saw. The screen test goes well and, in a few years (which pass in just a few pages of the book) Maggie Jones, having changed her name to Margaret Marshall, becomes the most popular Hollywood actress in America. Alas, the murder that she witnessed on her first day in Hollywood will continue to haunt her for the rest of her life. For one thing, Sam Lendt, though he finds himself forced to support her career, remains determined to destroy her someday. Lendt’s son died in the sanitarium and Lendt secretly blames Maggie for this.

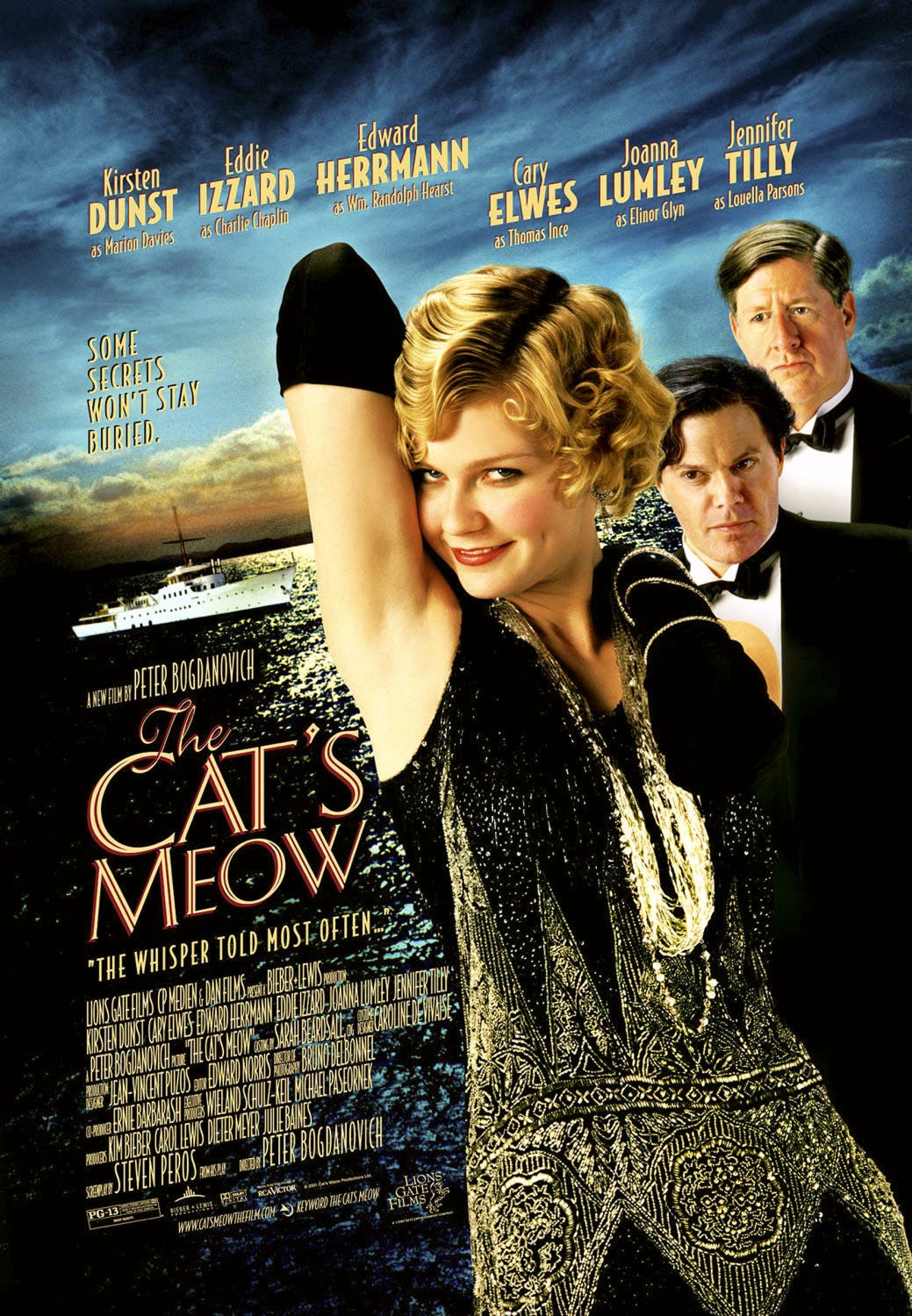

During the 1920s, Hollywood movie stars were still mostly clustered in high-end communities like Bel Air and Beverly Hills. Malibu was twenty miles away from Beverly Hills and still largely just a collection of beach houses where the wealthy could seek refuge whenever they needed a rest. But Maggie, who never saw the ocean until she moved to Southern California, becomes enamored of Malibu Colony right away and purchases a house there. Her section of the book deals with her rise in the film industry and her various romantic highs and lows. Eventually she becomes pregnant by Ben Montgomery, but he is married to another woman, a highly-strung former actress, so Maggie cannot expect Ben to acknowledge that he is the father of the child. Instead Maggie marries a kindly film director who is thirty years her senior. They pretend that the baby is his. Alas, Sam Lendt, upon learning that Maggie has given birth to a son becomes determined to kill the boy in retaliation for the death of his own son years earlier in a sanitarium. Lendt, of course, is too fastidious to do the work himself. Instead he informs Ben’s emotionally unstable wife that Ben is the father of Maggie’s son, Michael. Ben’s wife has just given birth to Brendan, Ben’s first legitimate child, and she becomes unhinged over the idea that Maggie and Ben have produced a child. And, of course, Sam Lendt knew this would happen. By informing Ben’s wife of Michael’s true parentage, Lendt has set in motion a chain reaction that will lead to several several murders and at least one suicide. Thus Maggie’s section of the book begins with a murder and ends with even more of them. It was my favorite section of the book and would work well as a short standalone crime novel. The character of Lyla Moran appears to have been at least partially based upon real-life actress Marion Davies. She becomes the kept woman of a fabulously wealthy man (based on William Randolph Hearst) who owns a chain of newspapers. Late in Maggie’s part of the novel a murder occurs aboard a yacht owned by Lyla’s wealthy lover. The murder seems to have been inspired by the rumors that for decades have swirled about the death of Hollywood producer Thomas Harper Ince. According to some, Ince was murdered aboard William Randolph Hearst’s yacht and then the police were paid off to rule the death a heart attack. This rumor inspired the 2001 Peter Bogdanovich film The Cat’s Meow.

Part Two of the book is set in the mid-1950s and deals with Michael and Brendan. These two men now know that they are half-brothers, both sired by Ben Montgomery. The two of them have inherited Maggie’s Malibu Colony home. Brendan is a sexually fluid film star and apparently his character was inspired by James Dean. Michael is a crusading journalist working in Los Angeles. The two brothers loath each other. They compete for the love of the same woman, Laura Hampton. Eventually Michael wins her hand in marriage. Enraged, Brendan rapes and impregnates Laura before racing off to meet an end somewhat similar to James Dean’s. Michael knows that his beloved daughter, Shannon, is really Brendan’s daughter, but this doesn’t lessen his love for her. The Michael/Brendan section of the book covers primarily 1953 and 1954. Like the first part of the novel, this part opens with a lurid murder — a mob hit. This section also could stand alone as short crime novel. I found it less compelling than Maggie’s story, but it is still very entertaining.

Part Three is set in the late 1970s and it concerns Shannon’s efforts to make a name for herself as a singer-songwriter. She has moved into her grandmother’s beach house in Malibu Canyon and loves it as much as her grandmother (whom she never met) did. She makes the acquaintance of a self-destructive but hugely successful female rock star who appears to be equal parts Janis Joplin and Linda Ronstadt. This section of the book involves a lot of drug abuse and some sexual abuse but is less overtly about crime than the other two sections. I enjoyed it although it is filled with a lot of cliches and seems to have been largely inspired by the 1976 Barbra Streisand film A Star is Born and the 1979 Bette Midler film The Rose.

Pamela Wallace grew up in Southern California and knows the milieu well. She won an Academy Award for co-writing the script of the 1985 Peter Weir film Witness, which starred Harrison Ford. As you might expect of a novel written by an Oscar-winning screenwriter, the dialog in Malibu Colony is sharp and cinematic. Malibu Colony may not be an all-time literary masterpiece but it’s a rock-solid piece of pop fiction. I wish it had dealt more with the history of Malibu’s rise to prominence as an enclave of Southern California’s rich and famous. A good novel that delves deeply into that history would be fascinating to read. Malibu Colony is a bit light on history but it evokes a sense of place very well and anyone who enjoys a good crime novel or a good multi-generational family saga ought to seek out a copy of it.

Although the heyday of the American city saga has passed, good ones still get published now and then. Honolulu, a 2010 novel by Alan Brennert, is an excellent, fairly recent example of the genre. While not every city saga is filled with criminal activity, most contain at least a soupcon of it. History and mystery are two literary genres that play well together. So why not make your next staycation a trip to Palm Springs or Galveston or Nevada or Cape Cod. You’ll find plenty of rot beneath those beautiful facades.