As of today, Sunday, December 15, 2024, I have read 106 books since January 1. I have mentioned before that I get irritated when I hear people bragging about reading an enormous number of books each week, or month, or year. To me, that’s like bragging about eating ten great meals a day. If you’re consuming food that fast, you probably don’t understand what food is all about. Likewise, if you read 500 to 700 pages an hour (as academic snob Harold Bloom claimed he did), you seriously don’t understand what reading is all about. I am somewhat embarrassed to note that I have been consuming books at a rate of about one every three days, but allow me to present a half-hearted defense of my literary gluttony.

A lot of the books I read are actually books that I am re-reading. And generally, when I re-read a book, I am doing it in order to write an essay about it, an essay that I hope to publish and make some money from. When I saw that Netflix was going to drop a new miniseries based on Tom Wolfe’s 2001 novel A Man in Full, I decided to re-read the novel so that I could write an essay about how well David E. Kelley’s miniseries compared to Wolfe’s book (not very, as it turned out). Wolfe’s book runs slightly over 730 pages in hardback. It is a massive novel in the manner of the great 19th century social comedies of writers like Balzac and Dickens and Thackeray. I read it shortly after it was first published and I remember wrestling with it for weeks on end, being alternately enthralled and exhausted by it. When I began re-reading it, I found myself skimming through certain passages of it, such as Wolfe’s tedious evocation of background noises. Wolfe wrongly believed himself to be a master of onomatopoeia, and thus he filled his books with passages such as these:

Buh buh buh buh bubba boooooo uh-ooooooooooo, the long soft ripe soupy notes of Grover Washington’s saxophone…Scrack scrack scrack scrack scraaaaaaaaacccccccckkkkkkkkkk, the grinding screech of the attic fans…Motherfuckin’ motherfuckin’ motherfuckin’ motherfuckin’, the motherfuckin’ chorus of one and all…Thragoooooooom thragoooooooooom, the roar of the toilets flushing…Glug glug glug glug glug glug glug, the sucking noise they made when they finished flushing…and then Motherfuckin motherfuckin’ motherfuckin’ motherfuckin all over again.

That’s a description of what one character hears when he sits in his jail cell at night. Stuff like that appears on nearly half of the book’s pages, and it starts to grate like a jailhouse attic. After awhile, I stopped skimming these passages and skipped them entirely. I also skimmed my way through some parts of the book that I remembered fairly vividly from my initial read. Thus I read Wolfe’s doorstop in just three or four days. But when I finished it, I felt like I knew it even better than I did after my first read. I also went back and read reviews of the book by John Updike, Norman Mailer, and a few others. I also read Wolfe’s essay “My Three Stooges,” in which he defended the book against the insults hurled at it by Mailer, Updike, and John Irving. Re-reading the novel, and reading about the novel, and then watching David E. Kelley’s TV adaptation of the novel, and then writing about both for Quillette, made A Man in Full seem like a major part of my 2024 literary journey. Thus I don’t feel guilty listing it among the books I read in 2024, despite the fact that I did a bit of skimming here and there.

In a similar vein, when I heard that the streaming service MGM + had adapted George R. Stewart’s classic 1949 sci-fi novel, Earth Abides, for TV, I decided to use that fact as an excuse to write an essay not just about Stewart’s novel but about the entire genre of post-World War II apocalyptic novels set in California. I am a longtime fan of Stewart’s and had read Earth Abides at least twice before. Thus, I did a bit of skimming when I was re-reading the book this time around. One of the California apocalypse novels that I re-read for the essay was Richard Matheson’s 1954 classic I Am Legend. This is a short novel (approx. 25,000-30,000 words). I’ve read it several times through the years, beginning when I was a teenager. I was a huge fan of the early film versions of the novel (1964’s The Last Man on Earth, and 1971’s The Omega Man), and I have read plenty of other work by Richard Matheson. I skimmed a bit while re-reading I Am Legend but, because I am so familiar with the material, I felt like I had once again relived the sad tale of Robert Neville in full. On the other hand, I began re-reading Philip K. Dick’s 1965 novel Dr. Bloodmoney and found myself so disenchanted with it, that I wound up skimming parts of nearly every page. As a result, I haven’t listed it among the books I read in 2024.

One of my favorite books of 2024 was Dorian Lynskey’s Everything Must Go, a nonfiction work about apocalyptic novels and films. I acquired it in order to do research for my California apocalypse essay. Rather than read it straight through, cover-to-cover, I looked up titles I was especially interested in (Earth Abides, I Am Legend, etc.) in the index and then sought out what Lynskey had to say about them. But even after I had finished writing my essay, I continued to delve into Lynskey’s 500-page tome. In the book, Lynskey writes quite a bit about John Wyndham and his so-called “cozy catastrophe” science fiction novels (The Day of the Triffids, The Midwich Cuckoos, etc.). I became so intrigued by what he had to say that I not only read (or, in some cases re-read) a handful of Wyndham’s novels, I also read some similar novels praised by Lynskey, including The Death of Grass by John Christopher (a penname for Sam Youd). I went back to Lynskey’s book again and again throughout the year, looking for apocalyptic book recommendations. I haven’t managed to read the entire book, and I probably never will. But I spent so much time with Lynskey’s survey of end-of-the-world stories that it felt like a major part of my 2024 literary project. In fact, it was sort of indirectly responsible for inspiring me to write my own sci-fi novel – Hey, Hey, Yesterday – which I serialized on Substack (more about that in a bit).

At any rate, in my capacity as Quillette’s unofficial authority on pop fiction, I re-read quite a few books this year – including Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City; Joe Klein’s Primary Colors; and Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War – so that I could write essays about them, and I occasionally skimmed my way through an overly familiar section. Nonetheless, I read enough of those books, and I read enough about those books, that they stood out as significant parts of my reading year.

I don’t believe that the reader of a book should consider himself a galley slave to the author. Likewise, I don’t believe that a film viewer should consider himself a galley slave to the film’s director. I am not a fan of excessive gore or violence in films, and I will happily fast-forward past such things when I am viewing a film at home on TV. If I have a DVD that offers both the theatrically released version of a film and the director’s cut, I will almost certain watch the theatrical version. In my experience, directors’ cuts tend to be self-indulgent and overlong. Many of the classic novels I have read in translation have been shortened in some ways by the translators. Constance Garnett’s translations of classic Russian works such as Anna Karenina, War and Peace, and The Brothers Karamozov, have been criticized through the years for prudishness and for omitting the gory details of fight scenes or the steamy exchanges of passionate lovers. But her major translations still have plenty of fans and have remained in print for a century or more. You can find longer and, perhaps, more accurate translations of great Russian novels and stories, but you are not required to. Many classic works of literature written in languages other than English are often slightly abridged when translated for contemporary American readers. Les Miserables, The Tale of Genji, The Three Musketeers, Don Quixote, the Ramayana, the Mahabarata, the Shahnameh – these are generally offered in editions that have been altered in ways to make them more accessible to contemporary Americans. Sticklers for the authors’ original versions may sneer, but I have enjoyed many of these modernized books. When I read Don Quixote, I chose the version translated by Samuel Putnam and included in The Viking Portable Library’s edition of Cervantes’ work. In his introduction to this abridged version, Putnam mentions several of the things he has deleted from the novel (usually tales-within-the-tale narrated by some random character and having little to do with Quixote and his quest). Putnam’s intro contains several observations such as, “I have had no scruple about deleting the goatherd’s meandering tale at the end of Part I.” And, “The captive’s story I have kept but condensed…” And [T]ake the romance in the latter chapters of Part I, which involves the two pairs of lovers. It is more than a little trite and bookish in flavor with complications that are finally resolved in a highly unconvincing deus ex machina fashion. This entire episode could, I think, be dropped without loss if it were not so interwoven with the main plot. I have accordingly condensed it insofar as possible, keeping only so much of it as was necessary.” I think of myself as someone who has read – and greatly enjoyed Don Quixote – but a literary purist might argue that I’ve not actually read the novel as Cervantes wrote it. Of course, this is true of every novel I’ve ever read in translation, abridged or not. And I am okay with that.

Even when I am reading a contemporary novel in English, I will sometimes skim or skip things. I generally find the practice of prefacing each chapter with long quotations from other books to be pretentious, annoying, and unnecessary. If each chapter is prefaced with a brief poem by Emily Dickinson, fine. I can handle that. But oftentimes the chapters of a novel set, say, in the Middle Ages, will be prefaced with long excerpts from nonfiction books about the era. This strikes me as either a vainglorious attempt by the author to show off how much research went into his novel, or else the work of a novelist who fears that his own writing is insufficiently authoritative to stand on its own. Generally, I feel that if a novelist wants to include a either a poem by Emily Dickinson or some fascinating fact from Barbara Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror in her book, she ought to find a way to incorporate it into the actual text. If the first one or two of these chapter prefaces prove unnecessary to my understanding or enjoyment of the novel, I will often simply skip the rest of them. Forty-one of the forty-two chapters in Jason Matthews’ excellent spy thriller Red Sparrow end with a recipe. I happen to be a foodie, so I read each of these recipes. But they have no bearing whatsoever on the plot of the novel and you could skip them and still thoroughly enjoy the novel. That kind of skipping doesn’t strike me as dereliction of the reader’s duty to the author.

I rarely do any skimming or skipping if I am reading a novel for the first time, but I do make occasional exceptions. Michael Crichton’s novels – particularly The Andromeda Strain and Airframe – occasionally include page upon page of computer printouts containing information that makes no sense to me. I just skip these printouts and let the subsequent narration explain their meanings to me. Earlier this year, I was reading a great medical thriller by Tess Gerritsen called Harvest. The main story concerns a young doctor, Abbie DiMatteo, who uncovers a secret cabal of medical men who are illegally harvesting organs and implanting them in wealthy people who need life-saving transplants. Apparently, in America, there exists a nationwide database of people in need of a transplant, and organs have to be doled out on a first-come-first-served basis (there are some exceptions, based on need, to this rule). If you need a new heart, your doctor puts your name on the heart-recipient list. You can’t use wealth or privilege to jump to the head of the queue. But the evil doctors in Harvest are enriching themselves by selling organs to the highest bidder. Many of these organs are harvested from young orphans living on the streets of the former Soviet Union. These kids are put on large transport ships in Russia and other former Soviet states and then shipped to the U.S., where their organs are harvested in secret shipboard operating rooms. To preserve their organs, the kids are kept alive and relatively healthy during the trip over. Naturally, they won’t survive the removal of their organs. Every fifty or sixty pages, Abbie DiMatteo’s story is interrupted so that Gerritsen can update the reader on the status of the children being brought from Russia for illegal organ harvesting. These passages, featuring children being horribly treated while at the same time they are led to believe that they are being sent to America to be adopted by loving families, were just too heartbreaking for me to endure. And they didn’t seem to be advancing the plot much. So I decided to skip the passages about the abused children until the ship reached America and their stories merged with Abbie DiMatteo’s. I enjoyed the novel a great deal, but I don’t regret skipping parts of it. Generally, when reading a book (or watching a film or TV show) I skip any passage involving the abuse of children or animals. Fortunately, I tend to avoid books that I suspect might contain graphic animal or child abuse, so I don’t have to do a lot of skipping when I read.

At any rate, of the 106 books I’ve read so far this year, I did a little judicious skimming in about twenty of them, mostly because I was re-reading a book I was already fairly familiar with. Thus, I am not quite the book glutton I may appear to be. I am not entirely happy about the fact that I am able to read a lot more books these days than in years past. I am 66 years old and, since leaving my job at an Amazon warehouse back in 2022, I have been unable to find another part-time job, despite having applied for dozens of them. No one seems to want an old man with few marketable skills – go figure! For the last two years, I have had plenty of time on my hands, and I have generally filled it by reading, writing, baking, and playing my banjo. I enjoy all those things, but I wish I had a little less time on my hands and a part time job that could get me out of the house a bit more and help supplement my Social Security payments. Ah, well, I shouldn’t complain. For a booklover, I’m in a pretty enviable position.

I generally begin my year with some sort of reading goal or agenda, and 2024 was no exception. My late mother was a devout fan of the gothic romance novels that proliferated in the middle of the twentieth century, inspired partly by the huge success of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. When I was growing up, our house was filled with cheap paperback books whose covers invariably featured beautiful young women fleeing in fear from spooky-looking old houses. I used to gently tease my mother about these books. They all looked so similar and so…cheesy. But my mother read more than just gothic romances. She loved pop fiction, and our bookshelves also contained cheap paperback copies of everything from Rosemary’s Baby to Jaws to The Exorcist to The Thorn Birds. It was through her that I acquired my passion for popular fiction. When she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, in her late seventies, she lost her ability to read or to communicate coherently about much of anything. I realized then that there was a lot I should probably have been asking her about through the years, questions about her life, and about her interest in books. It was now too late for me to do that, but I thought that I might gain some insights into my mother by delving into the gothic romance books that she loved so much. For the last ten or fifteen years, I have included some gothic romances in my reading diet, and I have generally enjoyed them quite a bit. More recently, I acquired a few serious literary studies of the entire mid-twentieth-century gothic-romance-novel boom. So my plan for 2024 was to read a lot of gothic romances, as well as books about the genre, and then write an essay explaining what this exercise taught me (or failed to teach me) about my mother. The very first book I read in 2024 was a 1969 gothic romance appropriately titled You’ll Like My Mother, which was written by Naomi A. Hintze. Like most gothic romances, this one was very short, only 159 pages, and I read it in a day. It was definitely cheesy and had some eye-rolling plot twists and character behavior, but it was also fast-paced and engrossing. It seemed like my Year of Reading Gothic Fiction was off to a good start. Alas, as with my New Years resolutions to lose some weight, my reading goals often go awry shortly after the beginning of the year. Such was the case in 2024.

Another one of my reading goals for 2024 was to read some crime fiction set in Santa Barbara, California, and then write about it. I’m fascinated by the way that some of California’s most upscale communities have inspired so many classic crime novels. In previous years, I’ve read a lot of crime and crime-adjacent novels set in Malibu, Pasadena, and other high-end California communities. Santa Barbara is the setting of most of Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer novels and Sue Grafton’s Kinsey Millhone novels (although both author’s fictionalize the city as Santa Teresa). For years, I had heard that Newton Thornburg’s 1976 novel, Cutter and Bone, was not just one of the best crime novels ever set in Santa Barbara but also one of the best crime novels ever set in California. Years ago I read and enjoyed his 1984 novel Beautiful Kate, but for some reason, I never got around to reading anything else by Thornburg. But my Santa Barbara project gave me an excuse to finally crack open my copy of Cutter and Bone. The book was so good that, upon finishing it, I immediately acquired a copy of his 1973 book To Die In California, another crime novel with a Santa Barbara setting, and began reading it. My Year of Reading Gothic Romance Novels and Crime Books With A Santa Barbara Setting seemed to be off to a great start. But it is difficult to stick to a reading plan when you are also determined to make money by writing about popular fiction for publication. As each new year approaches, I go online and see what famous novels might be celebrating a significant anniversary. In 2024, Earth Abides celebrated 70 years in print, and I Am Legend celebrated 75 years. Also, both Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Jaws turned fifty years old in 2024. So I re-read both of those books in an effort (successful!) to sell essays about them to Quillette. At about the same time, my editor at Quillette asked me to write about the whole Amityville Horror phenomenon because the MGM + streaming service had just released a multi-part documentary about it. For that essay, I not only re-read the original Amityville Horror book by Jay Anson, I also read Anson’s only other book, a novel called 666 (I skimmed so much of it that I won’t even list it among the books I read in 2024), as well as the books The Intruder, by Pat Montadon (surprisingly good), and Night Stalks The Mansion (weird, but not in a good way), by Constance Westbie and Harold Cameron, both of which were, like The Amityville Horror, marketed as true stories about haunted houses. As I recall, my Amityville Horror essay ended up not even mentioning 666, The Intruder, or Night Stalks the Mansion. I did write a separate essay about various Amityville wannabe books, but as yet I haven’t found a home for it. I’ll probably post it on Substack someday soon. At any rate, all this job-related reading totally derailed me from my two major literary goals, and I never got either project back on track. I can’t say that I regret this too much. I enjoyed reading almost all of the books that I wrote about for Quillette (Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance being a major exception).

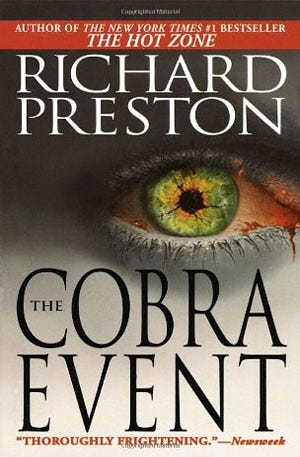

Despite the fact that my Santa Barbara and Gothic Romance projects got derailed, the year 2024 was marked by three fairly ambitious reading projects, none of which was actually planned. In January, I was in a Sacramento used bookstore when my eye was caught by a biological thriller called The Cobra Event, written by Richard Preston. The book was published in 1998 and I’ve seen it hundreds of times over the years in bookstores. I believe the reason I never took note of it is because it was published a few years after his nonfiction book The Hot Zone became a massive bestseller. If you are as old as I am, you may remember the buzz that accompanied the publication of The Hot Zone, a book that had originally been excerpted in The New Yorker. Stephen King proclaimed that it was “One of the most horrifying things I’ve ever read.” The publisher seemed to make every effort to make potential readers think that the book was a novel rather than a work of nonfiction. Blurbs on the paperback edition claimed the book to be “more terrifying than any sci-fi nightmare” and “a riveting thriller” and “an infectious page-turner” and “swashbuckling reading” and “a spine-chilling narrative” and “a fast-paced gripping medical thriller.” Lured by these come-ons, as well as by the recommendation of a usually reliable book-loving friend of mine, I rushed out an bought a copy of The Hot Zone in the late 1990s. Alas, I am not a huge fan of nonfiction books. I prefer my thrillers to be novels. The Hot Zone did, indeed, include a lot of gory and horrifying descriptions of how the Ebola virus attacks the human body, but it is a rather diffuse work of nonfiction that bounces around among various real-life scientists and sufferers, various years, various outbreaks, and it includes a lot of straight-forward science writing that simply isn’t all that engrossing if what you are looking for is a fast-paced medical thriller. It was an admirable book but it didn’t grip me the way a good novel always does. And I think I just probably assumed that The Cobra Event was another nonfiction thriller that used bookstore owners occasionally accidentally shelved in the fiction section. Thus, I took little note of it for years. But, in January, something inspired me to pull the book off a shelf at The Book Worm and take its measure. When I discovered that it was an actual novel, I bought it. According to my diary, I began reading it on January 14. Here’s how I ended my diary entry for January 15: “I sat up in bed till nearly ten reading to the end of ‘Cobra Event.’ It read like a collaboration between Michael Crichton and Thomas Harris ‘The Silence of the Andromeda Strain’ or, perhaps, ‘The Red Cobra.’ At any rate, it was a real page-turner. I loved it.”

For me, The Cobra Event was the first great thriller of 2024, and it didn’t just whet my appetite for more thrillers, it specifically got me craving more bio-medical thrillers. By January 16, I was online perusing lists of “the best bio-medical thrillers” and “great thrillers about disease” and “page-turning biological novels” and so forth. One book whose title popped up frequently was Cold Storage, a thriller about a killer fungus from outer space, published in 2019 and written by screenwriter (Jurassic Park, and many others) and director (Stir of Echoes, and many others) David Koepp. As it happens, I’m a big fan of Koepp’s film work, and I already had a copy of Cold Storage on my shelves, although I hadn’t read it yet. So I immediately set about reading my copy of Cold Storage and ended up loving it. I loved it so much, in fact, that I ordered a copy of his only other novel (to date), Aurora, published in 2022. This one wasn’t technically a bio-medical thriller, but it was about a solar storm so powerful that it knocks out nearly all of the electrical power on planet earth, leaving mankind to try to survive for months on end without any of the appliances and other conveniences that we take for granted. This is a plausible scenario. In 1859 a solar flare known as The Carrington Event blew out nearly all of the electrical devices on earth. Fortunately, at that time, telegraphs were about the only electrical devices in use. Aurora was every bit as good as Cold Storage – gripping, fascinating, terrifying, fun, over-the-top, suspenseful – and after reading it I cranked out two essays, each one celebrating one of Koepp’s novels. The essay celebrating Cold Storage is titled Great Big Gobs of Greasy Grimy Zombie Guts and was published on Substack on February 21. The essay celebrating Aurora – Boring Title; Thrilling Novel – was published on February 29. I won’t quote from them here, but I suggest that you check out both those essays or, even better, just buy both novels and settle in for some great pop fiction.

While searching for bio-medical thrillers online, I came across plenty of titles I was already familiar with, including Earth Abides and I Am Legend. It was when I noticed that both of those novels would be celebrating significant anniversaries in 2024 that I got the idea to write an essay about California novels of the apocalypse. But, while I was gobbling up Calipocalypse novels, I also continued to hunt for other bio-medical thrillers in the vein of The Cobra Event. One such book was Gwen in Green, a cult classic from 1974, written by the late Hugh Zachary. The book was mentioned by Grady Hendrix in Paperbacks From Hell, his brilliant 2017 study of the cheesy horror fiction boom of the 1970s and 1980s. The book was recently republished by Valancourt Books, featuring an introduction/appreciating by Will Errickson, whose author bio says he “co-wrote” Paperbacks From Hell (his name doesn’t appear on the cover but the title page credits the book to “Grady Hendrix with Will Errickson”). Gwen in Green is more of a botanical thriller than a biological one. It also qualifies, sort of, as a gothic romance. It tells the tale of a young married couple, Gwen and George, who move to a remote and largely undeveloped part of North Carolina’s Tidewater region, where they hope to build a home to escape the rat race in. It turns out that the land is cursed. Anyone who tries to cut down its old-growth trees or drain its swamps is likely to meet a horrific demise. Every generation or so, a woman comes along who can actually communicate with the land on a subconscious level, so much so that she becomes a sort of human defender of the land, helping whatever malevolent presence keeps the property largely undeveloped fight back against the men who would despoil it. It’s a weird novel, and it incorporates a sort of feminist message (women are of the land and protective of the natural world; men simply want to rape the land) with a lot of raunchy sex scenes that seem to have been aimed at Playboy magazine enthusiasts. At one point, the beautiful Gwen lures a young construction worker named Billy away from his bulldozer and into a secluded part of the property he is razing. She tells him to take off his clothes and he says, “You first.”

She nodded, shed the blouse in one graceful motion, loosened her hotpants, let them fall. She had a thick, brown bush and sweet-looking legs. She kicked the hotpants aside. Billy’s throat was dry. He took a step toward her. She said, “Now you.”

Billy obligingly begins to undress but this encounter isn’t going to go the way that he is hoping. In fact, it will end disastrously for him. Under the influence of the natural world that workers like Billy are trying to tame/eradicate, Gwen has become some sort of avenging earth mother, determined to protect her offspring. Gwen in Green is not a great book, but it is never dull. It seems to have been a sincere attempt to write a thriller that takes into account a lot of the ecological concerns that were beginning to turn the environmental movement into a major political force back in the 1970s (the first International Earth Day was held in 1970). Its weird mix of horror, environmentalism, raunchy sex, feminism, suspense, and disquisition on marriage makes it unlike most pulp thrillers of the era. It wasn’t the biological thriller I was hoping for, but I’m glad I read it.

About fifteen years ago, I read a novel by Tess Gerritsen, best known for her series of crime novels featuring Boston Police Detective Jane Rizzoli and Medical Examiner Maura Isles (the books were adapted into a TV series called, appropriately, Rizzoli & Isles). I no longer remember which Gerritsen novel I read back then. I remember liking but not loving it. I believe I made a vague promise to myself to seek out more of her work, but I never got around to doing so. Until 2024, that is. When I was looking up biological thrillers on the internet, Gerritsen’s name came up over and over again. I thought this was odd, because I assumed she wrote only Rizzoli and Isles crime novels. But I did a little online research and learned that Gerritsen is a bit of a Renaissance woman. Her birth name was Terry Tom, and she is the daughter of a Chinese immigrant and a Chinese-American. She was born in San Diego in 1953. She received an undergraduate degree from Stanford and then got a medical degree from U.C. San Francisco. She practiced medicine for several decades and her husband is also a doctor. Tess Gerristsen is both a classical pianist and a violinist, as well as a composer of classical music. She began her literary career in the mid 1980s, while on maternity leave from her medical career, and published a series of romantic suspense novels that were directed primarily at the readers of Harlequin romances and other low-prestige paperback publishing ventures that specialized in women’s fiction. Gradually her novels began leaning more heavily on thrills and suspense than on love and romance. Her 1990 novel Under the Knife, published by Mira Books, a division of Harlequin Enterprises, is more Robin Cook than Danielle Steel. In 1996, she published her first great thriller novel, the abovementioned Harvest. The book has garnered nearly eight thousand reviews on Amazon.com and has a rating of 4.6 stars out of 5. This is a thriller worthy of comparison with Thomas Harris’s Red Dragon and The Silence of the Lambs. I recounted the plot above, so I won’t repeat myself. What makes the book excellent is not just the expert pacing and plotting but the fact that it was clearly written by someone thoroughly steeped in how American medicine works, how hospitals are run, what a medical doctor’s workday is like, and so forth.

After Harvest, Gerritsen published several more top-notch medical and medical-adjacent thrillers. Her novel Gravity is a masterpiece, comprising a thriller set on the international space station, a bio-medical thriller, a love story, and various other gripping elements. Published in the year 2000, you could say, depending upon how you calculate these things, that it was either the last great American thriller of the 20th century or the first great one of the 21st. In either case, it is excellent. In 2001, she published The Surgeon, the first (and probably the best) of the Rizzoli and Isles novels, but even that book, as the title suggests, leans heavily on Gerritsen’s medical training. By my count, she has now published a total of 35 books. Her two most recent novels are spy thrillers. She is a gifted and prolific writer of popular fiction, but for some reason I largely ignored her until 2024. While looking for bio-medical thrillers, the first Gerritsen title I acquired this year was Bloodstream, published back in 1998. Here’s my diary entry for March 18, 2024: “Read more of ‘Bloodstream.’ Finished it at ten. Very good. A creepy biological thriller like ‘The Cobra Event,’ ‘Cold Storage,’ and ‘Gwen in Green.’” If that sounds like less than effusive praise, well, it was late at night and I was too tired to effuse much. But I enjoyed Bloodstream so much that I would go on to read another twelve novels by Gerritsen over the course of the year. Bloodstream is a science-fiction novel about a deadly fungus that has plagued the teenagers of a remote Maine town for generations. (Gerritsen and her husband live in Maine, which may partially explain why Stephen King is a huge fan of hers.) It can be enjoyed as a thriller, a horror novel, a crime novel, or a gripping medical story. After finishing Bloodstream, I got hold of a copy of Harvest and devoured it. Next up was The Surgeon, a medical thriller as well as a Jane Rizzoli crime novel. She followed it up with The Apprentice, also a bit of a medical thriller and the novel that introduced Maura Isles. In 2019, Gerritsen published The Shape of Night, a romantic suspense novel that was a bit of a throwback for her. In an essay for Substack I compared it favorably to both Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca and the 1947 film The Ghost and Mrs. Muir. Look up my essay (published October 18) if you want to know more about The Shape of Night. I enjoyed it a great deal, though it was less serious than most Gerritsen novels. Next I read Life Support, an excellent 1998 medical thriller. Many of Gerritsen’s thrillers use multiple timelines. An excellent example of this is The Bone Garden, a standalone thriller from 2009 which toggles back and forth between the present day and the 1830s, when a serial killer nicknamed the West End Reaper is terrorizing Boston and Oliver Wendell Homes (not the Supreme Court Justice but his father, a legendary Boston medical man) joins forces with those who hope to stop him. Maura Isles makes a cameo appearance in the present-day part of the story but this isn’t a Rizzoli and Isles novel. Gerritsen’s 2015 novel, Playing With Fire, is another standalone thriller that operates on two timelines, one in the present and one in Europe during the Second World War. Gerritsen put her musical background to good use in this story about a mysterious piece of music, composed by a Jewish prisoner at Italy’s only concentration camp. The sheet music is discovered in 2015 by an American musician, but when she plays it on her violin, it produces a seemingly disturbing effect on her toddler daughter. Danger, mystery, and suspense ensue. The past is often a big part of a Gerritsen novel, and she seems to be as fascinated by history as she is by medicine.

Among her many virtues as a writer is one that sets her apart a bit from other genre writers. She has an almost religious reverence for the dead. Dead bodies are commonplace in crime and mystery dramas, but they are mainly just used to set the story in motion. This changed a bit with the rise of the forensic crime novel/film/TV series, which began in the 1970s with the popularity of the TV crime drama Quincy, M.E. and really took off in the 1990s, when Patricia Cornwell published Post Mortem and its many sequels, all of which were bestsellers and followed the exploits of a fictional Virginia medical examiner named Kay Scarpetta. Now, suddenly, fiction writers were paying more attention to the dead, allowing them to act as “silent witnesses” in their own murder investigations. But still, oftentimes, the dead remained fairly minor characters in their own murder stories. As a writer of medical thrillers, Gerritsen explores not just murder victims but other deceased persons as well – victims of disease and disaster and historical cataclysms. Her 2008 novel, The Keepsake, has a lot to say about both Egyptian mummies and European bog bodies. She writes with clear disgust and hostility about the Victorian Era practice of bringing Egyptian mummies to England for irreverent uses. Here’s an Egyptologist character explaining the situation to Jane Rizzoli in The Keepsake:

“There was once a thriving international trade in mummies. They were ground up and used as medicines. Carted off to England for fertilizer. Wealthy tourists brought them home and held unwrapping parties. You’d invite your friends over to watch while you peeled away the linen. Since amulets and jewels were often among the wrappings, it was sort of like a treasure hunt, uncovering little trinkets for your guests…It was done in some of the finest of Victorian homes. It goes to show you how little regard they had for the dead of Egypt. And when they’d finish unwrapping the corpse, it would be disposed of or burned. But the wrappings were often kept as souvenirs.”

Her 2007 novel, The Bone Garden, taught me about the anatomy riots that took place in 18th and 19th century America. Back then, medical schools had no reliable source of corpses that could be used for the study of human anatomy. Thus, many medical schools hired grave robbers (often referred to as “resurrectionists”) to dig up the bodies of the recently deceased and bring them in secret to the school’s vivisection department. In fact, impoverished students sometimes put themselves through medical school by acting as paid ressurrectionists. Again, Gerritsen writes with barely concealed contempt about the treatment of the dead by these so-called medical men. Here’s an exchange between two of her characters”

“Becoming a doctor was one of the few ways to advance in society. Physicians were respected. Although while in training, medical students were viewed with disgust, even fear.”

“Why?”

“Because they were thought of as vultures, preying on the bodies of the dead. Digging them up, cutting them open. To be sure, the students often brought condemnation on themselves by their antics, by all the practical jokes they played with body parts. Waving severed arms out the window, for example…My father and grandfather were doctors, and I’ve heard these stories since I was a child…When I was growing up, my grandfather told me a story about a student who smuggled a woman’s corpse out of anatomy lab. He put it in his roommate’s bed, as a practical joke. They thought it was quite hilarious.”

“That’s sick.”

“Most of the public would have agreed with you. Which explains why there were many anatomy riots, when outraged mobs attacked schools. It happened in Philadelphia and Baltimore and New York. Any medical school, in any city, could find itself burned to the ground. Public horror and suspicion ran so deep that all it took was a single incident to touch off a riot.”

In a Tess Gerritsen novel, the dead are more than just silent witnesses of their own deaths; they remain fully human and as deserving of respect and dignity as any living person. Even the long dead – mummies, bog bodies – get treated with respect in Gerritsen’s fiction.

Her books are filled with fascinating scientific and historical information. In addition to all the info about mummies and bog bodies, The Keepsake also taught me about the Lost Army of Cambyses, a fascinating historical incident (possibly apocryphal) about an army of fifty thousand Persian soldiers that simply vanished without a trace in the Egyptian desert 2,500 years ago.

I intended 2024 to be The Year of the Santa Barbara Crime Novel and The Year of the Gothic Romance Novel. Neither of those things really came to fruition. But, among several other titles, 2024 became, for me, The Year of the Bio-Medical Thriller and The Year of the Tess Gerritsen Novel.

In addition to Richard Preston’s, Tess Gerritsen’s, and David Koepp’s bio-medical thrillers, I read several others deserving of mention. I gave in to all the hype surrounding Alex Michaelides’s 2019 mega-bestseller The Silent Patient, a psychological thriller that has an astounding 337,970 reader reviews on Amazon.com and an equally astounding 2,575,165 reader ratings on Goodreads.com. I always figure that approximately one percent of a book’s readers probably take the time to review it on Amazon.com. If so, that would mean that The Silent Patient has been read by more than 30 million people, which boggles the mind, because I thought it was utter rubbish, and I have a fairly high tolerance for bad popular fiction. But The Silent Patient didn’t strike me as merely bad or boring, it struck me as evil and despicable. The novel has some whopping surprises embedded in its tortuous plot, so I’m not going to spoil the book for you by writing a detailed review of it here. The book is beloved by millions, so if you are all curious about it, you should read it. My reaction seems to be a minority one, although when a book has nearly 350,000 online reviews, you can certainly find plenty of naysayers among them. The Silent Patient by itself has probably outsold Tess Gerritsen’s entire literary oeuvre. It has certainly sold far more copies than David Keopp’s two biomedical thrillers or Richard Preston’s The Cobra Event. This is depressing to contemplate, because Michaelides’s book is poorly written, populated by one-dimensional nonentities, and provides no real genuine thrills, just a few shocks and surprises that are the literary equivalent of Hollywood jump scares. It was easily the worst book I read in 2024. Nothing else even comes close to the level of awfulness found in The Silent Patient.

Carriers, published in 1995, was one of the better bio-medical thrillers I read in 2024. The book is credited to Patrick Lynch, which is a joint pseudonym for authors Philip Sington and Gary Humphreys. It seems likely that the novel was inspired by Richard Preston’s 1992 New Yorker article Crisis in the Hot Zone, which tells of an Ebola outbreak and was later expanded into the 1994 book The Hot Zone. Certainly the publishers of Carriers were hoping to create a connection between the two books in the minds of thriller lovers. The cover of the paperback edition features an excerpt from a USA Today review that reads: IMAGINE A BUG ONE HUNDRED TIMES MORE CONTAGIOUS THAN EBOLA. IT’S HATCHING IN THE INDONESIAN RAIN FOREST IN CARRIERS…” The back cover quotes a review that (somewhat confusingly) says, “This – along with Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone – is the fiction/nonfiction guide into the modern world of unknown diseases.” I point this out not to belittle the accomplishment of “Patrick Lynch.” Pop fiction has a long history of taking horrifying news stories – the advent of the atomic bomb, for instance – and turning them into riveting worst-case-scenario fictions such as Fail Safe and On the Beach and The China Syndrome. Sington and Humphreys were smart to take Preston’s nonfiction tale and crank it up to eleven via a novelistic treatment. Carriers is intelligent, well-written, and fascinating. My main problem with it was that it just seemed too darned ambitious. The story includes dozens of important characters. The action takes place all over the globe. The authors crammed in a lot of back-story that was necessary but frequently slowed down the primary narrative. Nonetheless, I’m glad I read it. It has garnered only 90 reviews at Goodreads.com but many of them are ecstatic in their enthusiasm for the novel. The book reminded me a great deal of Lawrence Wright’s 2022 pandemic thriller The End of October, which I read last year. Of the two, I think Carriers is much the better novel. But both seemed to suffer from being excessively ambitious, trying to say everything that could possibly be said about a deadly worldwide pandemic, when a more focused narrative would have probably made for a more gripping read. Both books also bear a strong resemblance to the film World War Z, another thriller about a worldwide pandemic and one family’s efforts to avoid becoming victims of it. World War Z succeeds because it stays fairly tightly focused on the Brad Pitt character and his wife and children. Carriers and The End of October would have been more successful if they’d adhered to the World War Z playbook. But World War Z is based on a novel that was published more than a decade after Carriers, so Patrick Lynch didn’t have the option as using is as a template for his own thriller. Nonetheless, Carriers is still a worthwhile thriller.

The Syndrome, a bio-medical thriller by John Case, was published in 2001, and it is another bio-thriller authored by two people (husband and wife Jim and Carol Hougan) employing a single pseudonym. A year or two ago I read and enjoyed an earlier bio-thriller of theirs called The Genesis Code (about an attempt to create modern-day clones of Jesus Christ – a reversal, sorta, of the plot of The Boys From Brazil). The Genesis Code was another thriller that suffered from being a bit too ambitious and scattered but was nonetheless pretty entertaining and intelligent. Alas, The Syndrome takes a different bio-medical what-if (brain implants that can render a human being pretty much a robotic slave of whoever controls the “neurophonic prosthesis”) and stretches it way beyond the breaking point. The book is smart and features some great ideas, but the authors try to cram too much into this story, which makes it confusing and, ultimately, exhausting. The Hougans wrote seven novels under the Case pseudonym and each Hougan also wrote solo novels under their own names (they were both journalists and produced a lot of nonfiction also). I may give their work another try at some point, but The Syndrome sort of soured me on them a bit.

I read The Cobra Event in early January and spent much of 2024 trying to find a bio-medical thriller that could surpass it. I found several that came close – Cold Storage, Bloodstream, etc. – but no book I read this year was as thrilling as The Cobra Event. Curiously, though Preston hasn’t written any other solo novels, he was hired by the estate of Michael Crichton to complete Crichton’s unfinished thriller Micro. That book was published in 2011. I attempted to read it a few years later. At that time, the name Richard Preston didn’t mean much to me. I knew him only as the author of The Hot Zone, a nonfiction book that didn’t really thrill me. My attempt to read Micro petered out after about one hundred pages. I wasn’t much disappointed by the experience. Unfinished novels that are completed by a second author after the original author has died are rarely any good (see, for instance, Poodle Springs, begun by Raymond Chandler and completed decades later by Robert B. Parker). I moved on and forgot about Micro. But after being blown away by The Cobra Event, I went looking for more fiction by Preston and that’s when I once again came across Micro. It is the only other work of fiction to which his name is attached. Now, suddenly, I was eager to give Micro another chance. I’m a big Crichton fan and I loved The Cobra Event. I decided that my earlier failure to appreciate Micro was probably my own fault. Now that I was a fan of both Crichton and his posthumous collaborator, I was sure to enjoy Micro. Wrong! I still couldn’t make it past the halfway point of this novel (which, as the title implies, deals with miniaturizing human beings a la Honey I Shrunk The Kids). Desperate for more fiction by Richard Preston, I went looking into his background and discovered that he is the brother of Douglas Preston, who has written or co-written something like forty novels. His best-known work has been written in collaboration with Lincoln Child. When I was a clerk at a local bookstore I sold quite a few Preston & Child novels to my customers but I never bothered to read any myself. Now I wandered down to that same bookstore (I no longer work there) and purchased a copy of Relic, published in 1995 and the first collaboration between the two men. Relic was an okay piece of pulp fiction and seemed to be intended as a mash up of Jaws and Jurassic Park. I enjoyed it although it was often a bit longwinded. Douglas Preston worked for eight years at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and he seemed to want to cram his novel full of information about how museums are run, the internal politics, the turf wars, and so forth. This stuff is occasionally interesting but it slows down the story. Also, I detected a slight pompousness to the writing, as if the authors felt that they need to talk down to their audience. After reading Relic, I sought out Douglas Preston’s first novel, Jennie, about an ape who is raised to believe that she is a human child. Last year I read Karen Joy Fowler’s novel We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, which tells a similar story. For some reason my personal library contains quite a few books with ape or monkey protagonists of one sort or another – Eva by Peter Dickinson, Congo by Michael Crichton, Ishmael by Daniel Quinn, Dark Inheritance by the Gears, Planet of the Apes by Pierre Boule, etc. So I thought perhaps I’d read a few more monkey books and then write an essay about the genre. Alas, I got bogged down in the early stages of Jennie and put it aside, thus causing my monkey project to stall out. Part of my problem with Jennie was that I detected that same pompousness of tone that had marred Relic, but in Jennie it seemed even more prominent. I suspect that the pomposity of the Preston & Child novels comes from Preston. I haven’t read his 2008 nonfiction book, The Monster of Florence, but this review on Goodreads.com, written by someone called Erica, seems to cleverly capture the pomposity that is apparently endemic to Preston’s writing:

Preston: Well, my New Yorker article about the Monster of Florence won't be published now thanks to 9/11, so I think I should write a book instead.

Editor: But will Americans really be that interested in unsolved lovers lane murders in Italy? We already have the Zodiac Killer and the Son of Sam. Let's make this book about you instead.

Preston: You're right. I am, after all, a Bestselling Author.

Editor: And don't let your readers forget it! I want at least one reminder per page that you're not just any old armchair detective, but a Bestselling Author.

Preston: I did move to Florence in the first place to work on my next novel... I never finished it, but I'll include a page-long plot description so my readers know what a genius I am.

Editor: Don't forget to name-drop all the interesting people you met.

Preston: I'll be sure to include the blue blood Italian nobility I became such close friends with. Even they were impressed by my writing skills! Did you know that Thomas Harris wrote Hannibal in this town? And that Harris was inspired by the Monster?

Editor: Okay, be sure to include that on every page as well so your readers make the connection that you're just as good as Thomas Harris. Now, who is this Spezi?

Preston: He's an Italian journalist that most Americans have probably never heard of, so I'll be sure to minimize his voice in my writing. He was arrested in the course of our investigation, but that's not the story here... the story here is how I helped him out using my influence as a Bestselling Author.

Editor: And this book will be your next bestseller! Be sure to write about how incompetent the Italian police are, just to give everybody Amanda Knox vibes.

Preston: Who?

Editor: Don't worry about it.

A little pomposity isn’t the worst thing in the world, so I may read some more Douglas Preston novels in the future, but I have little faith that any of them will rise to the level of Richard’s lone solo foray into the field of novel writing. It’s a shame that Douglas was the Preston brother who chose to devote himself fulltime to writing novels, because Richard is so much better at it.

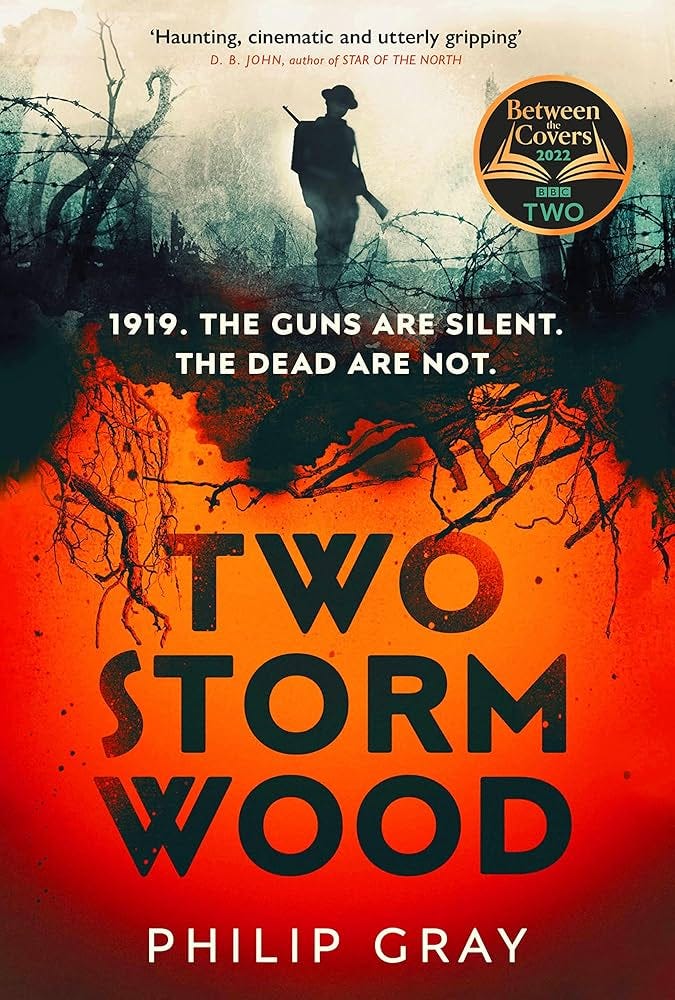

Now, let’s get back to Philip Sington – one half of the writing team known as Patrick Lynch. As it happens, Patrick Lynch isn’t Sington’s only pseudonym. He has also published a solo novel, called Two Storm Wood, under the name Philip Gray. Carriers was a solid piece of popular fiction, but Two Storm Wood is a near masterpiece and it satisfies the requirements of several major genres. It is a historical novel, a war novel (WWI and its aftermath), a horror novel, a romance, a mystery/crime novel, and it even flirts a bit with the fantasy and ghost story genres. I’ve read tons of WWI fiction, but I’ve never read one like this. The foreground story is set in the killing fields of France in 1919, shortly after the end of the war. I never gave much thought before to what happened when the war ended. I just assumed that all the British soldiers stationed in Europe – primarily France – just went home when the hostilities ended in November of 1918. Many of them did. But nearly a million of them couldn’t go home because, well, they were dead. And the British people didn’t like the idea of their fallen heroes lying in unmarked graves all across France. And so the British military undertook the enormous task of trying to exhume as many dead soldiers as they could from unmarked graves in French fields, identify them, and then ship them home for reburial. This, needless to say, was a grisly task that involved all kinds of body horror as men who had died gruesomely in battle and been left to rot in the ground for months or years now had to be exhumed. The task proved so arduous that the British military enlisted the help of the Chinese Labor Corps, a group of nearly 100,000 valiant men that I’d never even heard of before. These were mostly Chinese farm laborers recruited by the Brits during WWI to perform supporting roles for British troops so that more British soldiers could be sent to the battlefront. Although these Chinese laborers weren’t employed as soldiers, at least two thousand of them were killed during the war. And afterwards, the British paid many of them to remain in France and help exhume dead soldiers. Ordinarily, according to this novel, a fear of ghosts would discourage Chinese men from engaging in such an undertaking but, fortunately for the Brits, Chinese men fear only Chinese ghosts. British ghosts don’t frighten them. In fact, the Chinese don’t seem to believe that white men possess such things as ghosts and souls, and having just witnessed the white men of Europe massacring each other by the millions for the past five years, they can’t be blamed for harboring these beliefs. Thus, the Chinese laborers joined the British soldiers in the wretched business of digging up mutilated corpses in order to help posthumously repatriate them. Philip Gray/Sington does a good job of conveying the unspeakable horror of this task to the reader. I read a lot of novels in 2024 about horrific viruses that eat away the organs of human beings, funguses that essentially colonize human brains and turn their hosts into zombies, and corpses that explode in the international space station, where globs of their entrails and blood and viscera float through the weightless living quarters and spread their filthy infections to the living – but Two Storm Wood was probably the most grisly book I read all year. If you’re not familiar with the word “lingchi,” consider yourself lucky. Philip Gray provides a nauseating description of the practice in Two Storm Wood, and it’s only one of several god-awful examples of man’s inhumanity to man described in hideous detail in the novel. The book takes its title from a French field known as Two Storm Wood, a place where some horrific war crime appears to have been committed and then covered up. Powerful, sinister, and possibly even supernatural forces seem determined to keep the secret of Two Storm Wood literally buried beneath the ground. But those forces haven’t reckoned on the determination of one plucky young British woman, Amy Vanneck, a sheltered girl of the middle-class, who defies her entire community by insisting on traveling to France shortly after the end of the war in order to discover the fate of her lover, Edward Haslam, who is missing, presumed dead, and believed to have, at the very least, deserted his battalion during the height of battle and, possibly, even participated in the abovementioned hideous war crime. Before the war, Edward was a meek music-loving academic. He was a pacifist who opposed the war from the beginning. But when the fighting broke out, he eventually did his duty by the British people and enlisted in the military. Amy believes that he has been scapegoated for crimes that he didn’t commit and now cannot defend himself against. She also believes quite strongly that he may be still alive, hiding out somewhere in France until he can clear his name. And so she sets out for France – where both the British and French respond to her presence the way they might to a turd in a punch bowl – armed with almost nothing but her wits and a soul-deep conviction that Edward Haslam isn’t/wasn’t the coward he’s been condemned as.

Two Storm Wood is strongly reminiscent of Sebastien Japrisot’s brilliant 1991 novel A Very Long Engagement, another story about a young woman who sets out in the aftermath of WWI to find out what has happened to her fiancé, a soldier who was accused of shirking his duty and is believed to have died a coward’s death. But Two Storm Wood is neither a rip-off of nor a pale imitation of Japrisot’s novel. It has its own unique characters and plot twists and story structure and narrative voice. It is a very British story, whereas A Very Long Engagement is a very French one. I have described Two Storm Wood as grisly, hideous, horrific, and gruesome – and it is all of those things. So why did I enjoy it so much? Because it is a lot of other things as well. It is thrilling, mysterious, compelling, romantic, engaging, well-written, beautifully plotted, and features a marvelous heroine. It also has a few of those shocking plot twists that make you feel as if the floor has collapsed beneath your feet. For most of the time that I was reading it, I was convinced that Two Storm Wood would turn out to be my favorite book of 2024. It came close to winning that honor but Philip Gray didn’t quite stick the landing. After the mystery of what happened at Two Storm Wood is resolved and Edward Haslam’s fate is revealed, the novel continues for a bit too long, tying up loose ends that didn’t really need tying and explaining away things that might have been better left mysterious. The book is probably about twenty pages too long. This isn’t a major problem but the book was unputdownable for so long that I felt disappointed to find it overstaying its welcome. Nonetheless, this is a novel that I will almost certainly reread at some future time. The cover of my paperback edition has a great tagline: “1919. THE GUNS ARE SILENT. THE DEAD ARE NOT.” If you chose to read it, I guarantee that it will be one of the most unsettling thrillers you’ve ever encountered. Long after you’ve forgotten the specifics of the plot, there are things in this book that are likely to go on haunting your nightmares.

Amazingly, Two Storm Wood was only the second best of the Philip Sington novels I read in 2024. Under his own name, Sington has published three novels. The only one I’ve read is The Valley of Unknowing, published in 2012. The story is set in East Germany (generally referred to in this novel as The Workers’ and Peasants’ State, though it is anything but) in the late 1980s, a year or two before the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Berlin Wall, and The Workers’ and Peasants’ State. The protagonist is Bruno Krug, a middle-aged writer (and plumber) who published a single novel, The Orphans of Neustadt, in the late 1960s that, somewhat like The Catcher in the Rye or On the Road, became a cult hit amongst angsty, disaffected young people. It was successful across the globe but is especially revered by young East Germans, granting Krug a status among them similar to what J.D. Salinger had among young American hipsters in the 1960s. Krug followed up the novel with a less successful story collection and has written nothing since. Because his novel brought favorable attention to the East German literary scene, the state has granted him the status of People’s Champion of Art and Culture and given him a fairly nice apartment to live in and a stipend of some sort. But he also must work occasionally as a plumber, fixing toilets and faucets for workers and peasants, in order to make ends meet. He is approaching fifty and hasn’t published (or even written) anything in a long time. His publisher remains on friendly terms with him because Bruno’s novel is still fairly popular. For years people have urged Bruno to write a sequel to his celebrated novel, which had a famously unresolved ending and seemed to be written with a sequel in mind. Alas, Krug has turned out to be a one-novel wonder. And The Orphans of Neustadt never got the sequel so many fans were waiting for. But as The Valley of Unknowing opens, all that is about to change. In the opening pages of the novel Krug finds himself becoming infatuated with Theresa Aden, a beautiful young Austrian student who is studying the viola at an East German music school. Apparently, back in the day, when students from West Germany, Austria, and other nearby countries failed to get accepted into prestigious western universities, they sometimes chose to study at East German universities, which weren’t as picky about who they let in. Krug finds himself attracted to Theresa but there is a problem. She herself is infatuated with a young Wolfgang Richter, a cocky but talented young writer and political activist who frequently makes fun of Bruno King in his work. At this point, Bruno’s longsuffering publisher, Michael Schilling, gives Bruno an anonymous manuscript (no title, no author’s name) and asks him to read it and give an opinion of it. Reluctantly, Bruno takes the manuscript home with him and discovers that, although the characters’ names have been changed, the novel is clearly a sequel to The Orphans of Neustadt, which takes up where that novel left off. But, whereas The Orphans of Neustadt avoided any kind of political commentary that might upset government censors, this anonymous sequel is full of content that would get both the author and the publisher jailed if it were ever put into print in East Germany. Krug is both fascinated and outraged by this extension of his intellectual property. But he isn’t much worried about it ever being published. No one in East Germany would be suicidal enough to defy the government censors by publishing a book so replete with inflammatory content.

This plot summary covers only about the first twenty or thirty pages of the novel (I gave the book to a friend, who also loved it, so I don’t have it handy and can’t be exactly sure how many pages my summary covers). After that, all sorts of wild plot twists ensue but I don’t want to spoil any of them by revealing their nature here. The publisher compared the book to the excellent 2006 German film The Lives of Others, and it is a worthy comparison. The Valley of Unknowing has the kind of plot twists and shocking revelations that are more commonly associated with pulp fiction, but this is a fairly serious literary endeavor (the author’s wife grew up in East Germany and knew its horrors) albeit also a fairly comical one. The book is part Franz Kafka, part madcap adventure, part social commentary, with dashes of John Le Carre and Len Deighton thrown in for good measure. At times it also reads a bit like the work of Stephen King who frequently writes about fiction writers who find themselves in trouble (see Secret Window, Secret Garden; 1408; The Shining; The Dark Half; Bag of Bones; Lisey’s Story; Misery; ‘Salem’s Lot; and many others). Towards the end it also becomes unexpectedly moving (just as The Lives of Others does).

The book has garnered only 63 reviews at Goodreads.com, but many of them are ecstatic and reflect my own feelings about it. Reader Anna Kennedy writes:

“Oh I loved this book so much!! A beautiful gentle but powerful read, I was swept along in its current and was mesmerised by the emerging story as it was played out in its paranoia and self-doubt of an older man struggling with a young love which reflects his receding fame and success in East Germany. Highly recommended.”

Another reader, Jo, writes:

“This book was not only fascinating in its depiction of the German Democratic Republic two years before it fell, but also in the character of Bruno Krug, the writer at the centre of the story. Although Bruno's character is so flawed in many ways I never lost sympathy with him, I think because his flaws were so very human and primarily motivated by love. He does not come across as an evil man but simply a weak one and even though the prologue has already set the scene for a less than happy ending, the hope is there that he will find one.

“Sington's writing is a joy to read, there were so many lines and paragraphs I reread and tried to remember for their wisdom and their beauty and in contrast to the dreary scenery he describes so well, there was a lot of comedy in the book. Bruno's quest for toothpaste in a socialist state, for example had me smiling and this happened often in the first half of the book. The theme of betrayal, however, runs throughout the book: by the state, by informers and by lovers and so ultimately this is a somber book yet I found it a poignant, often exciting and engaging read.”

I couldn’t have said it any better myself. The book reminded me a lot of German author Sascha Arango’s 2014 novel The Truth and Other Lies, which is about a successful German novelist whose career is built upon a colossal lie. I read that book about a decade ago and loved it. I thought it was full of amazing plot twists and I enjoyed watching the evil protagonist trying to weasel his way out of one jam after another when it appears that his secret will finally be revealed. After finishing The Valley of Unknowing I immediately ordered a used copy of The Truth and Other Lies and then set about rereading it. Had I not read it so soon after finishing The Valley of Unknowing, my admiration for Arango’s novel might have remained undiminished. As it happened, I enjoyed the reread, but I now think that The Truth and Other Lies is a fairly superficial piece of entertainment (nothing wrong with that) whereas The Valley of Unknowing is both entertaining and a serious commentary on human nature. Arango’s book was published two years after Philip Sington’s and may have been partially inspired by it, though not in a plagiaristic way. I recommend them both.

If I didn’t already know it, I would never have guessed that Carriers, Two Storm Wood, and The Valley of Unknowing had all been written (or co-written) by the same person. All three books are incredibly intelligent, well-plotted, and fascinating. But Carriers reads like the best of Michael Crichton’s work; Two Storm Wood, while it bears some resemblance to A Very Long Engagement, is too original to be usefully compared with the work of any other contemporary popular writer; and The Valley of Unknowing, while it occasionally gestures towards Le Carre and Kafka and Stephen King, could never be mistaken for the work of any of those writers; it has a unique voice and a style all its own. And, unlike both Carriers and Two Storm Wood, which drag out a bit towards their finales, Sington stuck the landing in The Valley of Unknowing. The book didn’t end too soon or too late. I wouldn’t trim a single page from it. I’m not sure why Philip Sington isn’t better known. Maybe he should stop hiding behind so many pseudonyms. I think you can skip Carriers unless you are a hardcore fan of bio-medical thrillers, but anyone who loves a gripping and intelligent read ought to seek out Two Storm Wood and, especially, The Valley of Unknowing. Books like those are the reason readers like me write blogs like this.

Okay, so 2024 didn’t become The Year of the Santa Barbara Crime Novel nor The Year of Reading Gothic Romance Novels, but it did become The Year of Reading Bio-Medical Thrillers, The Year of Reading Tess Gerritsen Novels, and The Year of Reading Philip Sington Novels. What other titles can we assign to my reading journey of 2024? One such title could be The Year of Reading Calipocalypse and Caldystopia Novels, or books in which California is the setting for an apocalyptic or dystopian story. As mentioned above, I spent a good deal of time writing an essay that would celebrate both George R. Stewart’s Earth Abides and Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend. An abridged version of that essay, titled Abiding Legends: George R. Stewart, Richard Matheson, and the Birth of the Calipocalypse, was published at Quillette in July. A few months later, I posted the unabridged version of the essay here at Substack. Naturally this project required the reading or re-reading of a lot of apocalyptic fiction with a California setting. One of the novels I read for the project was Jean Hegland’s 1996 cult classic, Into the Forest. Several years ago I watched the 2015 film adaptation starring Ellen (now Elliot) Page and Evan Rachel Wood. I remember finding it mildly entertaining but nothing special, despite being a big fan of both Wood and Page (whose last names describe phases of the transformation of a tree into a book). Thus I wasn’t expecting to be dazzled by Hegland’s novel. But Hegland exceeded my expectations. Into the Forest may not be an all-time masterpiece of apocalyptic fiction, but it is a worthy entry in the genre. Just as George R. Stewart, in Earth Abides, largely ignored the more cinematic aspects of a worldwide apocalypse – large crowds of people flooding hospitals, somber TV newscasters delivering terrifying reports of death and destruction, politicians addressing the nation via radio and TV, etc. – and focused instead on how America’s manmade infrastructure – bridges, dams, reservoirs, roads, etc. – would quickly begin to fail without the proper maintenance, Hegland focuses on how a nationwide apocalypse – the result of a hemorrhagic fever that sweeps across America along with more fatal strains of TB and AIDS – two teenage sisters living alone in a rustic cabin located thirty-two miles outside of Redwood, California. Their parents have fallen prey to the pandemic and the sisters must somehow learn the survival skills necessary to stay alive in a world without any grocery stores, electricity, gas station, or police departments. The sisters occasionally get word of what is going on in far off places such as Los Angeles, Sacramento (my hometown) or even Boston, but for the most part focuses primarily on Eva and Nell and the few square miles that circumscribe their world. Their family life was somewhat fraught with dysfunction even before the death of their parents. But now things are immensely worse.

In some ways, Into the Forest qualifies as a bio-medical thriller, but readers seeking something akin to World War Z are likely to be disappointed. The various plagues that are rapidly depopulating America go largely unmentioned by Eva and Nell. They are too busy trying to keep themselves fed and to avoid being raped or murdered by marauding strangers to spend much time worrying about the fate of the rest of the U.S. And even if they did care to learn more about what was happening outside their own small piece of the world, they’d have almost no way of acquiring that knowledge. Into the Forest is a very claustrophobic and interior novel, two things I generally am not thrilled by in a work of fiction. But Hegland makes it work. Once I accepted the fact that Eva and Nell were not going to set off on a quest to seek out a community of fellow survivors somewhere in the Bay Area or L.A. or Sacramento, but were determined to simply stand their ground, I got into the spirit of Hegland’s novel, which is primarily a character study of two very different sisters and their struggles not only to survive but to get along with each other. This is definitely a “your mileage may vary” novel. I can imagine plenty of pop fiction fans being bored or disappointed by Into the Forest. My enjoyment of it came, in part, because I am a northern Californian, am familiar with the Redwood area, and I enjoy reading dystopian fiction with a specifically northern California flavor to it.

While researching George R. Stewart, I read his classic 1941 novel Storm, which details the progress of a massive Pacific storm that unleashes snow and rain that threatens to flood all of northern California and possibly wipeout all the city of Sacramento (the construction of the Folsom Dam in the 1950s severely reduced the possibility of Sacramento being wiped out by a flood and may even have been inspired, in part, by Stewart’s novel). This inspired me to seek out novels that seem to be heirs of Stewart’s storm, including Nathanial Rich’s 2013 rain-apocalypse Odds Against Tomorrow, which applies the Storm formula to New York City, and Lily Brooks-Dalton’s 2022 The Light Pirate, which applies it to the entire state of Florida. I wrote in detail about both Storm and The Light Pirate in Wanda and Maria: A Tale of Two Storms, which I posted to this blog on April 5 of last year. I suggest you seek out that essay, because I am not going to recap the novel here. I just want to point out that The Light Pirate, like Into the Forest, is a novel that is primarily interested in how an apocalyptic event affects female lives, specifically the lives of girls just growing into womanhood. Neither book struck me as a stone-cold masterpiece but they were both entertaining and thought-provoking.

Before we leave the topic of weather, let me mention another writer whose work I enjoyed in 2024, a woman named Beth Streeter Aldrich (1881-1954). In February, I read and greatly enjoyed her 1933 novel, Miss Bishop, which I described in my diary as “a cross between Good-bye, Mr. Chips and John Williams’s Stoner.” Miss Bishop is about a young woman who joins the first graduating class of a new American university in the Midwest. After graduation, she is hoping to spend maybe a few years teaching before getting married and then settling down to raise a family. Alas, fate has other things in store for Miss Bishop and she spends nearly her entire adult life teaching at the university whose inaugural graduating class she was a part of. It is a somewhat sentimental tale but is also filled with hardship and suffering and a clear-eyed view of how society treated childless, unmarried, working women in the early part of the twentieth century. I enjoyed it so much that I instantly sought out more of BSA’s novels. In short order I read her 1928 novel of pioneer life in Nebraska, A Lantern in Her Hand, and its 1931 sequel, A White Bird Flying. One of the interesting things about A Lantern in Her Hand is that it deals with man-made climate change. It tells the tale of a husband and wife, Will and Abbie Deal, who, shortly after Will returns from fighting in the Civil War, leave behind their Iowa home and travel by covered wagon to Nebraska to take advantage of the government’s Homestead Act. Like a lot of other pioneers they are hoping to farm several hundred acres of Nebraska land. But in the 1860s, Nebraska was an inhospitable place for farming. It was flat as a fritter and had almost no trees to break the powerful winds that swept across the landscape and made the winters incredibly harsh and cold. The pioneers that moved there knew all this. They also knew that if they planted long rows of tall trees they could create windbreaks that would literally alter the climate of the region. But it would take a long time for those trees to mature. And the pioneers knew that many of them would likely go broke or die before the windbreaks grew tall enough and strong enough to fend off the winds that frequently leveled the corn fields in the springtime and exacerbated the brutal blizzards and freezing temperatures of the winter. Early in the novel, when Abbie is exhausted and wants to give up, Will tells her (the italics are all in the original), “The land hasn’t turned against us. It’s the finest, blackest loam on the face of the earth. The folks that will just stick it out…You’ll see the climate change…More rains and not so much wind…When the trees grow. We’ve got to keep at the trees. Some day this is going to be the richest state in the union…the most productive.” Aldrich points out that it was J. Sterling Morton, a prominent Nebraska newspaper editor and businessman, who originated Arbor Day in America. On the first Arbor Day, held on April 10, 1872, one million trees were planted in Nebraska, and it wasn’t done for decorative purposes. It was done to alter the climate and slow down the winds. Liberals who think that climate change is an unintended consequence of fossil fuel use might be surprised to discover that mankind has been doing things to the planet to alter the weather for thousands of years (William Cronon’s 1983 nonfiction book, Changes in the Land, documents how the first American colonists altered the climate long before fossil fuels were in use). Conservatives who insist that mankind cannot alter the earth’s climate might be surprised that mankind has been doing so for thousands of years. In fact, those hearty pioneers who settled the West, and who are so beloved by conservatives, wholeheartedly believed that men could alter the climate, and they set out to do exactly that in places like Nebraska.