THE 2020 MIMSIES: Part II

WILLO DAVIS ROBERTS AND JANICE YOUNG BROOKS

The next two authors on my list are going to be seriously shortchanged by this essay. Janice Young Brooks and Willo Davis Roberts are two very underappreciated novelists. Brooks is still alive, but Roberts died in 2004. Both women wrote some incredibly good historical fiction. Both women eventually switched to writing mostly crime/mystery novels. According to an obituary in the Spokane, WA, Spokesman-Review, Willo Davis Roberts’ first 35 novels (out of a total of 100) were written for adults. But in the mid 1970s, she made a career switch and after that most of her novels were targeted at young-adult readers. Roberts was especially gifted at writing mystery novels for young readers, and garnered Edgar Awards for Best Young Adult Mystery from the Mystery Writers of America in 1989, 1995, and 1997. Meanwhile, between 1977 and 1992 Janice Young Brooks published a dozen historical novels. But in the late 1980s, using the pseudonym Jill Churchill, she began writing a series of mystery novels for grown ups known as the Jane Jeffry series, after the name of the title character. The mysteries won awards and became so popular that Brooks gave up the production of fat historical novels to produce shorter mysteries.

In 2020 I read multiple novels by both of these women. From Janice Young Brooks I read the epic 1981 historical novel Seventrees, which is set in Kansas during the years before, during, and after the Civil War. It follows three generations of women from a single American family and spans nearly a century. I enjoyed it so much that I immediately sought out more of Brooks’ historical fiction. The next book I read by her was 1990’s Guests of the Emperor, about a group of British, American, and Australian women who are captured by the Japanese at the beginning of World War II and spend four years together in various prisoner-of-war camps in the South Pacific. It is probably Brooks’ best-known novel due to the fact that it was turned into a 1993 NBC-TV movie starring Gena Rowlands and Annabeth Gish. Both books were excellent. I read a third novel by Brooks’ called Cinnamon Wharf, another historical saga. While impressive, I felt it lacked a little something. But Seventrees and Guests of the Emperor were both excellent and both are receiving Mimsie Awards this year. The reason that I haven’t written longer reviews of the two books is a bit complicated. I decided that I would write an essay for my editor at Ellery Queens Mystery Magazine about women writers who started out writing epic historical novels and then finished off their career writing shorter, less ambitious, but nonetheless very good mystery novels. This might seem like a pretty limited subject, but quite a few writers have actually followed this career path, including Gay Courter, whose novel The Midwife was reviewed above. Of course, some male authors have also followed this pattern, such as Oakley Hall, whose early novels (Warlock, Badlands, Apache, etc.) were historical tales and who, during the last decade of his life, turned to writing a series of mystery novels which featured real-life author Ambrose Bierce as a sleuth. At any rate, I put off writing long reviews of Seventrees and Guests of the Emperor until I had read more of Brooks’ crime novels. Likewise, I read two excellent historical novels by Willo Davis Roberts, 1980’s Destiny’s Women, and 1983’s Days of Valor. But when I learned that she spent the latter part of her career mostly writing mysteries for young adults, I decided to put off writing about her work until had read some of her mysteries. Now, here we are at the end of the year, and I still haven’t written the essay for the Ellery Queen editor, which means I don’t have reviews for these books. Well, that’s not exactly true. Earlier in 2020, when HBO announced that it was dropping the film Gone With The Wind from its streaming service because people were claiming it was racist, I wrote a long essay called Why You Should Give a Damn About Scarlett O’Hara, which discussed the entire genre of Southern plantation fiction. I mentioned that many novels exist that can serve as a corrective to the historical blindness of Gone With The Wind. One of the novels I recommended was on last year’s Mimsie Awards list, The Foxes of Harrow by Frank Yerby. Another of the novels I mentioned was Willo Davis Roberts’ Destiny’s Women. Here’s what I had to say about it in that (yet unpublished, alas) essay:

Sherman is a boogeyman in many a Southern plantation novel. But some writers are more scrupulously accurate in their history than Alexandra Ripley and Margaret Mitchell were. My favorite entry in the genre is Willo Davis Roberts’s Destiny’s Women, a tragically underappreciated 1980 novel that is now long out of print. The book’s paperback publisher marketed it as “The Magnificent Novel to Rival Gone With the Wind,” and it is pretty clear that Roberts was heavily influenced by Mitchell’s bestseller. Both books are about plantations in Georgia. In Destiny’s Women the plantation is called Mallows. It lies about 200 miles south of Atlanta. As the novel opens, Sherman is invading Atlanta and the occupants of Mallows and their neighbors are concerned that he will soon be burning his way through their own small corner of the state. But Roberts’ isn’t a simplistic tale in which the Union Army is bent on destroying the South while the Confederate Army is trying to protect it. Many of the Union soldiers and officers in Destiny’s Women are depicted as brave and conscientious men just trying to do an unpleasant job as humanely as possible. Some of the Confederates come across as equally honorable. But the novel takes place late in the war. Sherman’s Army is spread out in a line that is nearly sixty miles wide. The Union officers can’t keep track of every single soldier in the line. Thus some Union soldiers are depicted committing atrocities. But so too are some of the Confederate soldiers, both those who can see the handwriting on the wall and are deserting the Army in advance of its inevitable defeat and those who are still fighting.

One of the main female characters is nearly gang-raped by deserting Confederate soldiers (her sister shoots the main attacker dead and the others flee, but not until after the sexual assault has proceeded far enough to leave lasting psychological scars on the victim). Another young female character is gang-raped by Union soldiers and is so traumatized by the event that she eventually commits suicide.

Where Roberts really shines is in assigning voices and agency to her black characters. It is a commonplace of plantation novels that “house servants” (slaves such as butlers, cooks, and maids who work indoors) were treated much better than field hands and were considered practically part of the family by their white “employers.” This is certainly true in GWTW and Charleston. No doubt, there were advantages to working indoors rather than picking cotton all day under the hot Southern sun. But life as a house servant was no crystal stair. Female house servants spent more time in close proximity with their white masters than did outdoor slaves, which made them far more likely to be raped by those masters or their male relatives (a terrifying depiction of this phenomenon can be found in Willa Cather’s final novel Sapphira and the Slave Girl, a Southern plantation story published four years after GWTW). As the war winds down, the women of Mallows (the men of the family have all been killed or rendered invalids) are trying to convince their “house servants” to remain behind and help rebuild the plantation. At one point, Valerie Stanton, the book’s main character, pleads with Aaron, the slave who ran the household for Valerie’s mother, to stay on at Mallows and help rebuild it. “Haven’t we always been good to you?” Valerie asks him. Here’s Aaron’s response:

“Good to me?” For a moment sardonic amusement was reflected in the black face. “Oh, certainly, by your own lights you have been good to me, Miss Val.” The courtesy title was back, only said with an intonation that made it seem insolent, mocking. “As you would have been good to a little dog, except that I was not allowed to sleep on the foot of your bed. I have even been locked out of the house at night for the past two years because I was black, and you are afraid of black people these days. You can’t trust us, can you?”

When she made no response to this, Aaron tucked a knife into a homemade sheath at his belt and turned to go. At the last moment, however, he paused to look back at her.

“A young lady never been out of the state of Georgia is maybe bound to think the way you do, Miss Val. I s’pose you can’t help it, looking on niggers like they’re your pets or your mules, to do the work. I don’t know about the rest of them, running away to a place they know nothing about, with no skills except picking cotton. What I do know is that inside of me there is a man struggling to get out. Not a slave, not a servant, but a human being type man.”

After Aaron leaves, Valerie turns to Lallie, a young female slave and says, “You, too. You’re deserting, also.” And Lallie responds, “When the time comes. There’s no point in tryin’ to explain it to you. Aaron was right about that. Anybody with a drop of black blood will never be a human being to you, will they? Yet even a fieldhand yearns to be somethin’ more than a beast of burden, Miss Val. To be free.” Valerie doesn’t accept this, telling Lallie, “You’ve been cared for at Mallows, nursed when you’re sick as if you were a member of the family.” But Lallie is having none of that: “But I’m not a member of the family, am I? I’m nearly as white as you are, but I’ll always be a nigger in Georgia. And in this house, I’ll always take orders. Do this, Lallie. Do that. Don’t matter if I’m so tired I could drop, if somebody says Lallie, run up the stairs, Lallie runs. If I want to lay down and die, somebody says Lallie get up, and I get up. When Aaron comes back for me, I’m goin. So, you want to lock me out of the house at night, too? Just in case you can’t trust me, either?”

Valerie, desperate, says, “Are you in love with Aaron, then? Will you marry him? Mama would have let you marry him, if you’d told her…”

And Lallie responds, “Would she? White folks don’t have to be allowed to fall in love and get married, do they? They just do it.” The argument ends with Valerie defeated. But what’s interesting about this scene is that Valerie is the book’s main character and, for the most part, sympathetic. Books like Uncle Tom’s Cabin helped to generate the myth that all Southern slaveholders were evil sadists with no redeeming qualities. The value of a book like Destiny’s Women is that it shows that even good churchgoing Christian women like Valerie and her mother and sister, all of whom are by nature kindhearted, helped perpetuate the wickedness that was American slavery.

That’s where my review of Destiny’s Women ended in my article on Gone With the Wind. The review focuses only on how much more honest the book is about slavery than the novels of Margaret Mitchell and Alexandra Ripley. But a longer and more detailed review would also mention just how compelling the story is and how fascinating the characters are. The plot is like a Swiss watch. There is a climactic scene involving an unwanted wedding, an enormous chandelier, and a military sword that is downright operatic in its intensity. In some ways it reminded me of the famous chandelier scene in the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical The Phantom of the Opera. Sadly, Destiny’s Women is long-forgotten and out of print while Gone With The Wind remains not only the best-known novel of Southern plantation life but one of the best-known American novels of all time. I like GWTW a lot, but I think Destiny’s Women is the better novel. And it is a shame that it isn’t better-known.

Willo Davis Roberts 1983 novel Days of Valor is a historical epic about California, one of my favorite genres. In previous years I have written long reviews of other epic California historical novels such as Joanna Barnes’ Pastora and Shirley Streshinskey’s Hers the Kingdom. Heck, I began this essay with a long review of Jacqueline Briskin’s novel Paloverde, which is good but not nearly as impressive as Days of Valor. I mentioned Days of Valor in passing in my essay on American City Sagas, but since that essay was written for the Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine blog, I didn’t give it a prominent write-up, because the essay focused on city sagas that also succeed as mystery/crime novels. There is some crime and some mystery in Days of Valor but mainly it is a story of the growth of Knights Ferry, California, once the hub of Stanislaus County. The novel is nearly the equal of Destiny’s Women. But longer reviews of the books of Willo Davis Roberts and Janice Young Brooks will have to wait until I write my essay about female historical novelists who switched to writing mystery novels mid-career. Until then, suffice it to say that Destiny’s Women, Days of Valor, Seventrees, and Guests of the Emperor are four of the best novels I read in 2020, definitely within my top ten. Curiously, the spread of communicable diseases plays a role in all of these novels, and a cholera epidemic plays a major role in Seventrees, making all of the books even more relevant than ever during the pandemic year of 2020.

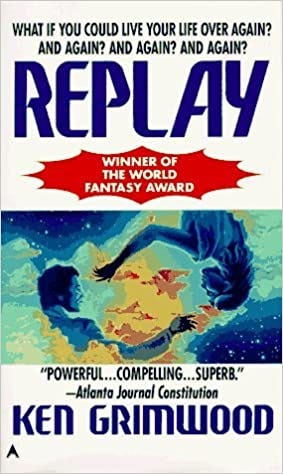

REPLAY

Perhaps because I watched so many episodes of The Twilight Zone, The Night Gallery, The Outer Limits, One Step Beyond, and other such Boomer-era TV shows in the 1960s, I was drawn to fantasy novels and fantasy short stories in the 1970s. Ray Bradbury, Fredric Brown, Richard Matheson, Jack Finney, Roald Dahl – I couldn’t get enough of their fantasy fictions. I have always considered myself a fan of fantasy fiction, but when I look back over my favorite books of the last few decades, I see very few fantasy novels. Apparently, as I have aged, I have become less interested in fantasy fiction and more interested in historical novels. Perhaps this is understandable. Fantasy (like sci-fi) tends to look toward the future, while historical novels look toward the past. Young people are often more interested in the future than the past. Old men, like me, tend to look backwards. When I made this discovery about myself – that I am no longer much interested in fantasy fiction – I felt sad, as though I had lost touch with an old friend. And perhaps that is why I was so thrilled to find myself enjoying Ken Grimwood’s novel Replay, a time-travel story that helped me travel back in time and revisit my lost boyhood love of fantasy fiction.

Replay was the last novel I finished reading in 2020. Published in 1987, Replay is not a lost or forgotten novel. It won the 1988 World Fantasy Award for Best Novel, has garnered over a thousand positive reviews at Amazon.com, and was republished, in 2016, in a fine leather-bound edition by the Easton Press, a treatment usually reserved only for very successful books (alas, Grimwood died in 2003 and didn’t live to see this honor). Nonetheless, I can’t help feeling that the book is underappreciated. It is far less well-known than many inferior fantasy novels (The Time-Traveler’s Wife, Somewhere in Time, Outlander, Timeline, etc.). And it seems to have influenced a number of far more famous fantasy properties that came later. In fact the entire do-over genre of fiction including the films Groundhog Day, The Edge of Tomorrow, and Palm Springs, as well as novels such as Stephen King’s 11-22-63, seems to have spawned from Grimwood’s book.

Replay is the story of Jeff Winston, a 43-year-old news producer at a New York City radio station, who drops dead of a massive heart attack in the first few pages of the novel, at precisely 1:06 p.m., October 18, 1988. But instead of ceasing to exist, he wakes up back in his old dorm room at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. The time is May of 1963. Although he finds himself back in his 17-year-old body, he still possesses all his memories of his previous life. He knows, for instance, that President Kennedy will be assassinated later in the year. He also knows who will win the Kentucky Derby that year and who will win the World Series. He uses his knowledge of the future to quickly amass a fortune by betting on sporting events whose outcome he already knows and by investing in companies that he knows will soon become darlings of the stock market. He founds a company of his own, Future, Inc., which becomes hugely profitable. He makes an attempt to prevent the Kennedy assassination. And when his effort fails, he pretty much gives up on the idea of altering major world events and spends the next few years increasing his fortune and pursuing love in all the wrong places. Eventually he goes to Boca Raton, Florida, and tries to woo his former wife, Linda, but this time around she wants nothing to do with him. Eventually he marries a woman named Diane and, though their marriage is a troubled one, they produce a daughter, Gretchen, who is the love of Jeff’s life. He takes great care of himself physically. He exercises regularly to keep his heart strong this time around. He is rich and can afford the finest medical care. And yet, at 1:06 p.m., on October 18, 1988, he suffers a massive heart attack, dies, and once again finds himself back at Emory University in 1963.

This cycle will repeat itself over and over again throughout the novel. Replay is not just a fantasy novel. If Replay had been written by Stephen King, it would have been made into a major motion picture no later than 1990 and would probably now be undergoing adaptation as a quality TV series for HBO, Amazon Prime, or Netflix, something along the lines of Under the Dome, 11-22-63, and Castle Rock. But, as much as I admire King, I’m glad he didn’t write Replay. If he had, the book would probably have built to some huge apocalyptic finale. Instead, Grimwood gives us a quiet, hopeful but not fully resolved finale which focuses on the ordinary human aspects of Jeff Winston’s life and not on the apocalyptic possibilities of the extraordinary time loop he finds himself trapped in.

Ken Grimwood was working on a sequel when he died at age 59 (Replay’s epilogue hints at a sequel that covers the years 1988-2017). Had he lived long enough to complete a sequel, it might have triggered a new wave of interest in the first book. Although I lament his death, I’m glad he never produced a sequel. I think Replay is damn near perfect as it is.

MASQUERADE

The next Mimsie Award winner is Masquerade, written by Cecilia Sternberg (a Hungarian Countess, pictured above with her husband and daughter) and published in 1979. Earlier this year I wrote a long and detailed essay called Forgotten Women about Sternberg and her only novel (it’s also about another forgotten female novelist, Jamey Cohen). The essay was posted to Janet Hutchings blog Something Is Going To Happen. I recently posted a longer version of the essay to my own Substack blog, so I shan’t write a long review here. I’ll just say that Masquerade was one of the oddest and most enjoyable novels I’ve encountered in a long time. It was produced by a woman whose full name was CountessAugusta Cecilia von Reventlow Criminil Sternberg. She is almost certainly the only crime writer whose last name at birth was Criminil. I can’t imagine what inspired this woman to sit down near the end of a long life and pen a single thriller novel, one involving Nazis, golems, and long-dead Russian Tsarinas, but I’m glad she did. I only wish that she had begun writing pop fiction earlier in her life. She might have left us a handful of masterpieces to equal Masquerade. If you want more details about the novel, you can check out my Forgotten Women essay. But it contains some spoilers, so I recommend that you skip the essay and get your hands on a copy of the novel as soon as possible. You won’t regret it.

THE SEVENTH STONE

Rising Sun, a deeply researched muckraking novel written by Michael Crichton as a warning about the rise of Japan’s economy and its threat to the U.S., was published in January of 1992. By March 1, it was the bestselling novel in America, according to the New York Times. The Seventh Stone, a deeply researched Japanese family saga written by Nancy Freedman and dealing with some of the same issues as Rising Sun, was published just a few months later, in April of 1992. It never got anywhere near a bestseller list. This, of course, was understandable. Rising Sun was the first novel published by Crichton after the monster success of Jurassic Park in 1990. He had been a name-brand author since the publication in 1969 of The Andromeda Strain, the fifth bestselling book of that year. His string of bestsellers was long and impressive. Nancy Freedman was best known as one half of the writing team that produced the 1946 novel Mrs. Mike, a minor classic co-written by her husband, Benedict. Nothing she had written since then had managed to garner much attention (although, curiously, she wrote a novel about cloning way back in 1973, a full 17 years before Jurassic Park and long before most Americans had even heard of the subject). Which is a shame. The Seventh Stone is a much better novel than Rising Sun and has held up better to the ravages of time. For a while, in the late 1980s, it looked as if Japan might actually soon overtake the U.S. as the biggest financial power in the world. But by the time these two novels were published, in 1992, Japan’s economy was already heading into a ten-year lull known as The Lost Decade. Although Rising Sun is, nominally, a murder mystery, most of Crichton’s energy is directed towards his breathless warnings about how huge Japan’s economy was growing. In an afterword, he writes: “The fact is a country the size of Montana, with half our population, will soon have an economy equal to ours.” Twenty-eight years after Rising Sun was published, Japan now accounts for about 5.8 percent of global economic activity, while the U.S. accounts for about a quarter of all global economic activity (the coronavirus pandemic may well skew these figures for at least a little while). These days the alarmists tend to be more concerned about China than Japan. In August of 2020, the online journal Quillette published an essay by Imran Said, a freelance journalist who specializes in Asian economic issues, in which he wrote: “America’s share of the world economy has remained virtually unchanged since 1980, when it accounted for 25.2 percent of world GDP. As of December 31st, 2018, the U.S. share only dropped to 23.9 percent. Over the same period, Japan’s share of world GDP fell from 9.7 percent to 5.8 percent…” Today Crichton’s novel is merely quaint, like those old Sputnik-era warnings that the USSR would soon be colonizing the moon, leaving America badly behind in the space race.

But there is nothing quaint about The Seventh Stone. Freedman’s tale includes some of the same information as Crichton’s. For instance, she notes that, by 1989, Japan was the world leader in the production of HDTVs, while America was no longer even competitive in that line. Like Crichton, she compares lazy, decadent, entitled America to hardworking chip-on-its-shoulder Japan and finds the former sadly lacking in competitiveness. If this were all there were to Freedman’s novel, it would now be as forgettable as Rising Sun. Fortunately, there is much more to it than that. The Seventh Stone is a big epic family tale, set mostly in Japan, which stretches from the days before the Pearl Harbor attack all the way up to 1989. Its focus is the Sanogawa family, a distinguished clan of wealthy business people. The first major character we come to care about is Noboru Sanogawa. When the war broke out, he was a young man and a prime candidate for the military. But his father intervened on his behalf by convincing the military that Noboru was a vital part of the family’s business operations, which were now transitioning from the production of toys to the production of missile-guiding systems. In reality, Noboru was never much of a businessman. He feels guilty staying home when most of the men of his generation are off fighting and dying in the war. To cheer him up his father arranges for him to marry a young beauty named Momoko. This actually works. From the moment Noboru lays eyes on her he is smitten. They marry and begin trying to conceive. Alas, Noboru’s mother, Yoriko, despises young Momoko and makes her life a living hell. When Momoko becomes pregnant, Yoriko calls her a slut and accuses her of becoming pregnant by someone other than Noboru. This is more than the poor little weakling Noboru can stand. To spite his mother he volunteers to become what the Japanese called an Oka fighter and what Americans refer to as a kamikaze (kamikaze means “divine wind” and referred to the entire project; the individual “pilots” were known as Oka fighters, and the “planes” they flew as Oka bombs). This was a sly (though suicidal) form of rebellion by Noboru. By 1945 Japan’s military was in dire straits and desperate for Oka fighters (ironically, because it had trouble guiding its bombs and missiles at American aircraft carriers, which were having their way with the Imperial Navy by then; had the Sanogawa factory been better at producing missile-guiding systems, there might have been no need for Oka fighters). Yoriko is horrified to hear that Noboru plans to fly a suicide mission, but she cannot object. To die for the Emperor was considered a great honor. And in the desperate final weeks of the war this was more true than ever. All Noboru’s parents can do is wish him well.

At the Oka training facility in Okinawa, Noboru becomes fast friends with a young man named Takeo Kurada. Takeo has been training for longer than Noboru when Noboru gets assigned to a suicide mission. Takeo begs Noboru to switch missions with him. He has been waiting longer to die for his Emperor. Noboru at first refuses, but eventually agrees to draw cards to settle the issue. Takeo draws the high card. The mission is his.

Early in the novel, I learned all sorts of fascinating things about Oka fighters. I always thought kamikaze pilots simply crashed military jets into their targets (which, of course, would be incredibly wasteful). Oka fighters are not actually airplanes. They are short-range gliders that are attached to the bottom of a mother ship (see illustration above). They have no real engines; just three booster rockets that can be fired to speed up the bomb’s diving speed after it has found its target. In the nose of an Oka bomb is a thousand pounds or so of high explosives. The fighter’s job is simply to glide over an American warship and then go into a nosedive, trying to crash into the ship before the guns on the ship can blow the Oka bomb out of the sky. Luckily (or not) for Takeo, his Oka bombing mission is aborted because the mother ship experienced engine problems and had to return to base. He is that rare Oka fighter who actually survived his mission. Noboru isn’t so lucky. His mission is…successful. He hits the deck of an American warship and is blown to pieces. His memory, will haunt his family for generations, especially his mother, his wife, his son, his cousin, his grandchildren, and, of course, Takeo, who spends his life trying to atone for the fact that, had he not cajoled Noboru into swapping missions, Noboru would have survived the war and Takeo would be the dead hero.

This is just the set up for a long and fascinating family saga. After the war, Takeo insinuates himself into the Sanogawa family, eventually marrying Momoko and acting as a stepfather to Akio, the only son of Momoko and Noboru. When, after several years of trying, Momoko fails to give Takeo a son of his own, she insists on divorcing him, despite the fact that they love each other desperately. In the society they are a part of, a woman who does not give her husband children shames him in the eyes of the world. Takeo doesn’t want the divorce but he reluctantly accepts it, and marries a woman who can give him children. Akio, who loved his stepfather, suffers permanent psychological damage as a result of the divorce. He becomes, basically, a psychopath, filled with hatred for his mother, his former stepfather, and most of the rest of the human race (especially Americans). After some early troubled years, however, he learns how to hide his near insane anger at the world and eventually rises to become the head of the family business and a highly respected man in the Japanese corporate hierarchy. He also becomes a crazy rich Asian, and he uses his money and power to exact revenge against all sorts of unsuspecting targets, including his son Juro (who was born legitimate) and his daughter Mako (who was sired out of wedlock with his mistress and raised by her grandmother, Momoko). Not until late in the story, do the people closest to Akio realize just what a monster he has become and what a threat he presents to them (and others). Some of them will work together to try to bring him down, but the odds are against them. Akio has an entourage of powerful yakuza (gangsters) who help enforce his iron will.

In addition to a deep desire to control the lives of his family members, Akio has two other passions: the ancient game known as go, and the islands known to the Japanese as The Northern Territories (at the end of World War II, they were taken from the Japanese and given to the USSR as the spoils of war and are now known, outside of Japan, as the Kuril Islands). The game of go (which I know almost nothing about) infuses nearly every page of the book and every decision made by Akio (who learned the game early and has been obsessed with it ever since). Even the book’s title is a reference to go. Clearly it is not necessary to understand much about go in order to enjoy the book, but I imagine it might deepen the experience. I suspect that a lot of the plot twists and story arcs mimic the feints and reversals of a competitive go game.

Likewise, I know little about the Kuril Islands, but Akio, like a lot of Japanese of his generation, is obsessed with a desire to see them returned to Japanese control. At the peak of his business career (and near the climax of the book) he believes he has found a way to return the Kuril Islands to Japan. Towards this end he embarks on a complex business venture that involves offering the U.S. government some high-tech equipment that will render their submarines much more efficient and nearly impossible to detect by radar. When the technology has been perfected, he will not sell it to the Americans but give it to them only if they can successfully act as a go-between with the Soviets and Japan in Japan’s effort to reacquire the Kuril Islands. Akio’s plan is bold and daring and crazy complex, but if he can pull it off he believes he will have gone a long way towards avenging his father Noboru’s death and erasing much of the humiliation of Japan’s defeat in WWII.

The Seventh Stone belongs to a genre of fiction that, as noted earlier, I call The Children of Shogun because, like James Clavell’s massive epic, they are concerned mainly with Asia and Asian characters but written by Occidental writers. In the decade and a half after Shogun’s huge success created a demand for other Asian epics, an impressive number of these books were published. Not all of them were very good. The Seventh Stone ranks with the best of them. Rising Sun, by the way, doesn’t qualify as a child of Shogun because (a) it isn’t an epic (the story unfolds over a mere three days) and (b) it takes place mainly in Los Angeles.

The recent literary tempest that brewed up when an Anglo writer (Jeanne Cummins) had the temerity to write a novel (American Dirt) set almost entirely in Mexico and featuring Mexican characters, may well have a chilling effect on authors who might want to write about cultures other than their own. We can only be grateful that Nancy Freedman, a Jewish-American born in Evanston, Illinois, felt no compunctions about writing a novel set in a country other than her own. Alas, the book is currently out of print and probably always will be. But used copies are easily acquired online. If, like me, you love a good Asian saga in the grand manner of Shogun, do yourself a favor and grab hold of The Seventh Stone.

THE SEEDS OF SINGING

The Seeds of Singing by Kay McGrath was one of the first books I read in 2020. According to my diary, I began reading it on January 18 and finished it on January 30. Here’s what I wrote about it on January 30: “Spent several hours reading to the end of The Seeds of Singing. It is nearly the equal of Omamori. Set mainly in Indonesia (especially New Guinea and Borneo), it follows the exploits of Catherine Morgan, a young American anthropologist, and the many people in her orbit. The book starts in 1939 and ends in 1966, but the biggest section of the book covers the years of the Second World War. It will almost certainly be near the top of the Mimsie list for 2020.”

I should have written a review of The Seeds of Singing as soon as I finished it, because it is a long, complicated story and very difficult to summarize now, nearly a year after reading it. Catherine Morgan’s on-again/off-again love interest is a young Harvard-educated anthropologist named Michael Stanford, the brother of Catherine’s college friend Julienne. Michael’s character was probably inspired by Michael Rockefeller, a real-life Harvard grad with an interest in anthropology who disappeared in New Guinea and is believed to have been eaten by cannibals. Michael Stanford and Michael Rockefeller share a first name and both possess the last name of one of America’s best-known nineteenth century robber barons (so does Catherine, for that matter). They have other things in common which I shan’t disclose here.

The Seeds of Singing is exactly the kind of lost or forgotten American pop fiction that I love most. It is not a refined and tasteful literary masterpiece. Rather it is a kind of hybrid of a variety of popular genres: romance, adventure, historical, war novel, etc. Though a hardbound edition was published in Great Britain, the American edition was a paperback original. Not much information is available online about the author. Apparently Dell, the American publisher, paid handsomely for the rights to the novel and gave it a strong push. A review in the January 2, 1983 edition of the Washington Post Book World by Barbara Mertz, noted that “Dell is making this its number one book for February, and it will probably do quite well. Some readers may even sob aloud at the ending, as Susan Moldow, Dell's editor in chief, claims she did…”

Like a lot of fiction written by and marketed to women, The Seeds of Singing was packaged as a romance novel, albeit one full of adventure. The paperback’s cover illustration features the requisite beautiful young woman with plenty of cleavage, but it also shows a man with a gun and plenty of jungle foliage, hinting that this is more than just a tale of star-crossed lovers. Indeed, the romance between Catherine and Michael feels almost tacked on at times. From various online sources I learned that author Kay McGrath received a B.A. in Journalism from the University of Missouri and a Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology from the University of California at Berkeley. It was psychology she chose as a profession and she spent part of her career in private practice and part of it in various public mental health clinics and crisis centers in Los Angeles. After retiring, she and her husband took up residence in suburban Virginia, outside Washington, D.C. She has never published another book. The Seeds of Singing was a 2000-page manuscript when she submitted it, over the transom (i.e., sans literary agent), to Dell in 1982. The odds of such a massive manuscript by an unknown writer without an agent getting a serious reading from a major publishing company are extremely slim, but according to a brief bio of McGrath on Google Books, the editors at Dell found the story so compelling they began passing it around between them and fell in love with it.

The similarities between this book and my favorite book of 2017, Richard McGill’s Omamori, are numerous. The authors’ last names sound similar. Both books were published in the 1980s. Neither author ever published another book. Both books are set in the Far East and much of the action takes place during World War II. Both books are obscure but adored by a small cult of fans. I can’t find a photograph of either author online. Both stories are historical romances that required a great deal of research. Both books have a popular-fiction aesthetic (as opposed to a serious literary aesthetic), something that is hard to define but has something to do with the fact that the authors are more interested in telling a crackling good yarn than in playing around with tricky chronological devices or narrative voices or various other acts of post-modern gamesmanship. The writing in both books is competent but never aspires to be much more than that.

Kay McGrath seems to have understood that, as an unknown female writer with no MFA or any apparent connections in the publishing world, her best shot at getting into print was to write a romance novel. But her real interest seems to have been to write a novel that would explore the culture of the various head-hunting and cannibalistic tribes of New Guinea and Borneo. She clearly wanted to explain these tribes to contemporary Americans, most of whom know little or nothing about the subject, so she chose an American as her viewpoint character. Out of convention, she gave Catherine a love interest, but the best scenes in the book are mainly just those in which Catherine explores the lives and mores of some of the region’s most mysterious tribes. McGrath also does a good job of describing just how exotic the natural world of New Guinea and Borneo are to a city-born American. When the war comes, there is additional interest in seeing how the natives of the region, who loathe their Dutch colonizers, find themselves loathing their Japanese invaders even more.

As for McGrath’s prose, well, Catherine’s heart seems to “skip a beat” every ten pages or so. Likewise, her “knees go weak” a bit too often for my taste. Standard romance clichés abound and weaken the book but don’t come close to sinking it. Fussy readers who run from the sight of any sort of pop-fiction convention will never make it through this massive novel (667 pages of tiny print in paperback). This raises interesting questions about what exactly constitutes popular fiction, as opposed to serious fiction that happens to be popular. After all, Toni Morrison has sold far more books than Kay McGrath, but nobody categorizes Morrison as a pop-fiction writer. As mentioned above, for me there is a genuine pop-fiction aesthetic, one that prioritizes excitement and enjoyment over artistry and enlightenment. Which is not to say writers of pop fiction don’t care about good writing and intellectual content. Most of them do. But their works are characterized mainly by a desire to entertain. Serious literary writers prioritize fine writing and intellectual complexity over lesser values such as entertainment and enjoyment, but that doesn’t mean that no serious writer wants to entertain her readers. It is a matter of priorities and every reader will make different judgments about what qualifies as serious fiction and what qualifies as popular fiction (it would probably be more accurate to use the terms intellectual fiction and entertaining fiction, though even those terms are problematic).

At any rate, no literary hack looking for a quick buck could ever produce a book like The Seeds of Singing. It appears to have been years in the making and to have required countless hours of background reading. Literary snobs can dismiss it as second rate if they want, but no one can in good conscience dismiss it as a potboiler. For better or worse, this book was written out of a sense of passion for its subject and not just for money. Of course, sincerity isn’t everything. No less an authority than Oscar Wilde assured us that “All bad poetry springs from genuine feeling.” Plenty of bad fiction also springs from genuine feeling, but not all fiction written from genuine feeling is bad. The Seeds of Singing is the kind of book that I find fascinating both for its virtues and its flaws. I never spent too much time wondering why John Updike wrote his nineteenth novel or Joyce Carol Oates her thirty-forth. Those people are professional writers and it’s their job to bring out a new book every year (or every six months in Oates’ case). But what inspires a Richard McGill to write his one and only novel, a complex story steeped in Japanese history and culture? What inspires a Kay McGrath to sit down and write her one and only novel, a complex story steeped in the history and culture of Indonesia? Oftentimes books like these make up for their relatively minor literary defects with power and passion and complexity. It’s hard to imagine a successful novelist, the kind who reliably brings out a book every year or two, setting aside the four or five years (at least, and probably many more) that must have gone into the researching and writing of The Seeds of Singing and Omamori. Which is why books like that are often one-off literary oddities produced by writers who apparently had only one book in them. Plenty of bad books also come from literary oddballs with only a single story inside of them. The fact that some massive, heavily researched piece of pop fiction was written by an author who produced no other novels is no guarantee of its quality. But every now and then, when you come across one of these one-off pop-fiction marvels, it is a delight.

I read The Seeds of Singing near the very beginning of one of the most challenging years in living memory. Even in an ordinary year, I’d probably have had difficulty writing a detailed review of it eleven months later. But though I write this in December of 2020, January of 2020 feels as though it was ten years ago. I can no longer give you a detailed review of The Seeds of Singing. All I can say about it is that it was one of those novels that seem to take over your entire life during the days or weeks that you spend reading it, a totally immersive experience. The writing can be fairly ordinary at times, a few of the characters seem overly familiar, but the milieu is fascinating, the plot is relentless, and Catherine and a few other characters are engaging and believable and only slightly larger than life. Not until July of 2020 would I come across a novel that I liked more.

SHAMAN’S DAUGHTER

The battle for second place this year was tough. I loved The Seventh Stone, Masquerade, and The Seeds of Singing so much, that I hated to choose between them and, to be honest, could easily have arranged those books in any order. They were all basically tied for second place. There was no battle for first place. Shaman’s Daughter, written by Nan E. Salerno and Rosamond M. Vanderburgh, was the best book I read in 2020. It was very intelligent, very well researched, very well written, expertly plotted, incredibly moving, and highly original.

Published in 1980, the book tells the story of Supaya Cedar from the age of twelve, until practically the hour of her death. Though it has a brief prologue and a brief epilogue, both set in 1967, the story proper begins in 1897 and most of the events take place in the first half of the twentieth century. When we first meet her, Supaya is experiencing one of the most important days of her young life, the day in which she discovers that her spirit animal is a Great Bear, which suggests that she shall live large and be an important person among her people, and maybe even among the white people also. Supaya is an Ojibwa Indian and lives in a village called Stone Island, in Ontario, Canada. Her mother is dead. She lives happily with her father, her older brother, and her maternal grandmother. She spends much of her time with her cousin Kineu Bruley, with whom she is in love. Supaya and Kineu attend a local school run by a white schoolmarm named Agatha Harris. Miss Harris, a devout Christian and sister of the local minister (an excessively pious and unpleasant man), refers to Supaya and Kineu as Sophia and Kenneth. She is determined to rid them of their Indian ways and indoctrinate them in the ways of the white man. Though misguided, Miss Harris is kindly and a good teacher. Her brother, the Reverend Nathan Harris, is a tyrant who brooks no Indian behavior. His mission is to Christianize the natives, by which he means to turn them into obedient churchgoers totally in his thrall. This tug-a-war for their souls is the greatest hardship that Supaya and Kineu face in the early part of the book. It is a battlefield that Supaya is gifted at negotiating, behaving like a proper schoolgirl in Miss Harris’ presence, and reverting to her Indian ways whenever she is out of school. Kineu finds it more difficult to navigate. He prefers to spend his days fishing rather than attending school. Despite the occasional difficulties, Supaya is happy with her life and she and Kineu both assume that they will one day marry and raise a family.

Alas, one day Supaya’s father, Jules Cedar, informs her that she can never marry Kineu because Jules has already promised her to another man, a man she has never met, the son of a powerful shaman named Wenonga Red Sky. Making matters even worse, Wenonga and his son live on a reservation far from Stone Island, the land where Supaya and her family dwell. If she goes off with Wenonga to marry his son, she will see her family members again only rarely, on visits separated by many years. Naturally this comes as a shock to Supaya. Her father feels awful about what he has done. But many years ago, before Supaya was born, Wenonga Red Sky saved the life of Jules’ wife (Supaya’s mother) when she fell ill after giving birth to her son, Jacques. As payment, Jules promised he would allow his firstborn daughter to marry Wenonga’s firstborn son. As it happened, Jules’ firstborn daughter, Neegonas, didn’t have to marry Wenonga’s firstborn son, because the son was killed. But Wenonga has a younger son, and now he intends to marry him to Supaya. Jules had hoped that the death of Wenonga’s firstborn son would end the Cedar family’s obligation to Wenonga. But now he knows that the obligation remains and that he is honor-bound to marry Supaya to Eli Red Sky, Wenonga’s second son (Neegonas is already married, and thus cannot take Supaya’s place). Thus Supaya travels with Wenonga to his far-off home and marries his son Eli.

Eli is, to say the least, poor husband material. He was taken from his parents at an early age and forced to attend a boarding school run by whites. During his formative years, when he should have been learning how to hunt and fish from his father, he was instead trained as a carpenter, a trade he had no affinity for and never became very good at. After graduating from the white man’s school, Eli Red Sky returned home to his family and his own people. But having spent so many years among white people, he no longer feels at home in either world, the world of his own people or the world of the white man. This makes him angry much of the time. He is prone to violence and prone to over-indulge in alcohol and also to cheat on Supaya with other women. This is a great hardship for Supaya, but she survives it by throwing herself into her work as a healer and a dispenser of herbal remedies. She also earns money by making baskets out of porcupine quills and then selling them wholesale to Jess Fallon, a local merchant who befriends Supaya and whose role in her life will grow throughout the novel.

The novel isn’t marred by the political correctness that nowadays makes it difficult to find a villainous Indian in contemporary literature. The book is populated by a variety of complex human beings, some of them whites and some Indians. Supaya’s father-in-law, Wenonga, is one of the most interesting of these. In some ways he is quite villainous. He knows from the beginning that his weak-willed son Eli will never be able to satisfy or tame a woman as spirited and independent as Supaya. Wenonga is attracted to Supaya sexually and plans to make her his own lover someday, by force if necessary. Supaya gradually becomes aware of Wenonga’s interest in her and does her best to avoid him. Eventually, however, he decides he has waited long enough and tries to rape her in one of the most frightening scenes in the book. But Wenonga is not completely bad. He is a gifted healer. He is a powerful leader of his family and widely admired, and feared, in his community. He is intelligent and cunning. His people have been deeply wronged by the whites who have colonized his ancestral land, and much of his anger and violence stems from this historic injustice. Although he is capable of great villainy, it is impossible for the reader not to have some sympathy and respect for the man. Other than Supaya’s, his is the most powerful presence in the novel.

Although Eli proves to be a terrible disappointment as a husband, Supaya nonetheless remains loyal to him. Not until she and Eli have been married for six years, does Supaya finally have the money and the self-confidence to travel back to Stone Island alone for a visit with her family. When she returns, after several days of travel, her father, Jules, asks her about Eli. “Does he bring home much meat, fish?”

Supaya informs her father that Eli was raised at a government boarding school and doesn’t hunt nor fish. He is a carpenter.

“Is he a good husband?” Jules asks.

“He is my husband,” answered Supaya proudly, with a flash of her old anger.

Eli, like many of the Indian characters in the novel, has had his spirit warped by his government education. Though he can be violent and abusive, he is by and large a sympathetic character. The reader can’t help wondering how much better his life would have been had he been left alone by the whites and their government school.

Over the course of this densely plotted novel, Supaya will end up having several lovers and husbands. She will give birth several times. She will study medicine under an ancient Indian medicine woman named Beedaubun, who will pass along to her knowledge of many herbal remedies and other folk medicines. Her skills as a healer will make her highly respected not only among her own people but also among certain members of the white community.

Shaman’s Daughter is essentially the story of a people trying hard to hold on to their ancient way of life while living in the midst of a white culture that has no respect for it. Supaya is better than most at walking the fine line that allows her to keep a foot in both cultures. But she sacrifices a lot in order to walk this line. Her cousin Kineu will go off to fight in World War I, hoping the sacrifice he makes on behalf of Canada’s white government will help him be embraced by the white community when he returns. Naturally, he is wrong about that. Though he survives the war physically, a big part of him never returns from the battlefields of Europe.

Although most of the Indians in Shaman’s Daughter face bleak fates as a result of losing their way of life to the white men who long ago took over the land of their ancestors, the novel itself is not overwhelmingly bleak. By focusing on the story of one very tough female who is able to adapt time and again to enormous changes in her way of life, the authors give us hope that at least some vestiges of the old ways can live on in survivors like Supaya. And, despite all the harshness to be found in its pages, the book contains much beauty as well. There are the majestic northern landscapes in which much of the story unspools and which the authors describe so well. Supaya does eventually find love and a sort of hard-won happiness, if only for a while. And she manages to either defeat or simply outlast most of her worst enemies. Of all the fictional characters I encountered in novels this year, Supaya is the strongest and most memorable. She doesn’t do anything world-shaking over the course of her long life. But her ability to just survive and live on her own terms despite being a woman in a man’s world and an Indian in a white world makes it impossible not to admire her and feel moved by her life story.

The book is a bit of a curiosity. It was apparently a minor bestseller back in 1980. The paperback edition carries quotes from enthusiastic reviews that appeared in The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, and other major publications. The reviewer for the San Francisco Sunday Examiner & Chronicle wrote, “This unforgettable heroine personifies womanhood with all its implicit needs and strength…Yet always retaining her own identity, her own distinct individuality…A truly remarkable novel.” A reviewer for the Detroit Free Press noted that, “The authors have a deep understanding and knowledge of the Ojibwa culture.” And a reviewer for The Lone Star Book Review asserted that, “To read the story of Supaya is to sample the peaceful confidence of a soul in harmony with nature and to feel a flood of regret for the passing of an era.” The book appeared during an era in popular fiction (the last three or four decades of the twentieth century) when a lot of novels about Native Americans were being published. Many of these books were written by women. I Heard the Owl Call My Name, written by Margaret Craven and published in the U.S. in 1973, Hanta Yo, written by Ruth Beebe Hill and published in 1979, and Sacajawea, written by Anna Lee Waldo and published in 1984 are three of the best known. Other prominent titles in the genre include Susan Donnell’s Pocahontas ( published in 1991, with a paperback cover — shown above — nearly identical to the one on Shaman’s Daughter), Lucia St. Clair Robson’s Ride the Wind (1982) and Walk in My Soul (1985), Orenda (1991) by Kate Cameron, and E.P. Roesch’s Ashana (1991). The genre was somewhat adjacent to the prehistoric novels of authors like Jean Auel, Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, Sue Harrison, William Sarabande, Charlotte Prentiss, Linda Lay Shuler, and the husband-and-wife team of W. Michael Gear and Kathleen O’Neal Gear. One odd thing about Shaman’s Daughter is that it was co-written by two women who never again collaborated on a literary project. Indeed, only Nan F. Salerno published another novel, Falling Uphill (1981), a tale of marital discord among the upper middle-class. Prior to working on Shaman’s Daughter, Rosamond M. Vanderburgh had published one previous book, a work of nonfiction called I Am Nokomis Too, about a real-life Indian woman. From what little is available about them online, I’ve learned that Salerno lived in Fredonia, NY, and was a professional editor and writing instructor, while Vandenburgh was an Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Toronto. How these two came together and produced such a seamless and stirring piece of popular fiction, I do not know. And why they never collaborated again, I also don’t know. What I do know is that the partnership produced one of the best books about Native American life (or, to be more precise, First Nations life in Canada) that I have ever read. It is a densely plotted novel whose intricacies I was able only to touch upon above. Reading it is an immersive experience that pulls you in to another person’s life and, when you finish it, leaves your own life much richer for it. I think a little bit of Supaya will remain inside me for the rest of my days. At least I hope so. She is an inspiring character, one who meets every challenge with admirable pluck and courage and intelligence. And the book that tells her story was my favorite of this dismal year of 2020.

THE LIST

Because I wanted to review all the labor novels together and all of the books by Willo Davis Roberts and Janice Young Brooks together, the books are reviewed above in an order that doesn’t quite reflect which ones I liked best. So, to correct that problem, I now give you the correct order of the Mimsie Award winners for 2020:

1) Shaman’s Daughter by Nan E. Salerno and Rosamond M. Vanderburgh

2) The Seeds of Singing by Kay McGrath

3) The Seventh Stone by Nancy Freedman

4) Masquerade by Cecilia Sternberg

5) Call the Darkness Light by Nancy Zaroulis

6) Replay by Ken Grimwood

7) Seventrees by Janice Young Brooks

8) Destiny’s Women by Willo Davis Roberts

9) The China Card by John Ehrlichman

10) Galveston by Suzanne Morris

11) The Last Sunrise by Norman Carelius and Verna Kidd

12) The Midwife by Gay Courter

13) Emmeline by Judith Rossner

HONORABLE MENTIONS:

Paloverde by Jacqueline Briskin, The Lonesome Gods by Louis L’Amour, Julie by Catherine Marshall, and Rivington Street by Meredith Tax

ALL THE OTHER BOOKS I READ IN 2020 (with a bit of commentary)

Palm Springs by Trina Mascott. This was a hugely enjoyable piece of pop fiction that tells the history of Palm Springs’ rise from a small town that catered mostly to TB patients seeking dry desert air to heal their lungs to a playground (and home ground) of the rich and famous. I included a long review of this book in my essay on City Sagas, which I will be posting to my Substack site very soon. Despite a few flaws, I highly recommend this forgotten out-of-print book.

Nevada by Clint McCullough. This too was incredibly entertaining and informative. And a long review of it can be found in my City Sagas essay.

Fabulous at Fifty by Diane Pearson and Jenny Haddon. I became a huge fan of the novels of British author Diane Pearson over the past couple of years. Alas, I had read all of her published novels by the end of 2019. But I was desperate to read something more by her, so I went online and ordered a used copy of this oddity. It is a brief and anecdotal history of the Romance Novelists Association, a U.K. organization dedicated to promoting British romance novelists and their work. Pearson was the president of the association from 1986 until 2011. In 2010 she and collaborator Jenny Haddon put together this fascinating history of the association. It includes short profiles of many interesting writers, most of whom I’d never heard of. It includes lists of the annual prizewinners for Best Novel. It includes a lot of gossip about what goes on behind the scenes at an RNA event, gossip about the personalities of some of the more famous members of the group (i.e. Barbara Cartland), gossip about all sorts of other stuff. Although it is nonfiction and filled with facts and biographical detail, it actually is very entertaining and amusing. What’s more I learned about a lot of books I probably wouldn’t have ever heard of otherwise.

Phantom by Susan Kay. I learned of this book by reading the previous book, Fabulous at Fifty, a history of the U.K.’s Romance Novelists Association. For years, most British Romance novels were relatively slim affairs. This began to change in the late 1970s. Fabulous at Fifty notes that Valerie Fitzgerald’s massive Indian historical novel Zemindar and Susan Kay’s Phantom were the first really long novels to win the Association’s top prize for a novel (the name of the prize has changed through the years, so it is usually just referred to as The Major Award). Intrigued I ordered a copy of Phantom (I have a long and complicated relationship with Zemindar, which I will write about in some other essay). Phantom, published in 1991, is a novel with a very strong following. At Amazon.com 689 readers have written reviews of it, almost all of them glowing. At GoodReads.com 875 people have reviewed the book and over 11,000 have rated it. Almost all of the reviews and ratings are raves. I can understand the enthusiasm for the novel. The book retells the story originated in The Phantom of the Opera, a 1910 novel by Gaston Leroux, which has spawned numerous offspring in other media, including films and stage musicals. The original novel doesn’t delve too deeply into the birth and youth of its main character, Erik, aka The Phantom. It focuses mainly on his tragic downfall. Susan Kay reimagines the character so thoroughly that hers should probably be considered the definitive story of The Phantom of the Opera. She gives the tale incredible breadth and sweep. It is a story that follows Erik through a miserable turn as a freak in a traveling gypsy carnival to a man who consorts with royals in fabulous Persian palaces. It really is an amazing tale, and if you have any interest in the story, you should make Kay’s version the first one you read. For much of the time I was reading this lurid and complex and fast-paced tale I was convinced that it would be a Mimsie Award winner come the end of the year, not the top book of the year but somewhere on the list. I was amused by this notion because, at the time, the favorite for Best Book of the Year was Kay McGrath’s The Seeds of Singing, and I thought it might be interesting if the book at the top of the list were written by a woman whose first name was Kay and the book at the bottom of the list were written by a woman whose last name was Kay. Alas, the last third of Phantom proved too much for me. Though it remained interesting until the end, it just began to drag on once I passed the two-thirds mark, and the story, which is filled with wholly unbelievable set pieces and plot twists just became too much of a muchness as it limped towards the finish line. I’m glad I read the book. Many people love this novel the way it is, so I’m probably wrong when I say that it would have been a much better novel if it had been about 100 pages shorter. Still, I feel like I should give it some sort of special award for being probably the most inventive and plot-heavy novel of the year.

Petersburg by Emily Hanlon. This was another near miss for me. After reading the first 150 pages I was convinced that this book would be a serious contender for a top spot on the Mimsie Awards list. It deals with the failed Russian Revolution of 1905, which became a dress rehearsal for the more successful Revolution of 1917. The opening chapters set up some really interesting dilemmas for a group of sympathetic and memorable characters. For a long time the pages just flew by. But somewhere around mid-book I found my attention beginning to wander. Scanlon clearly did a lot of research into the subject, but by mid-book she began artlessly dumping too much of it in. Also, curiously, the tight unsentimental prose of the novel’s first half frequently gave way to stomach-churning romance-novelese in the second half. Here’s a garish example of what I’m talking about: “Loving Anna brought him to the threshold of life, where stolen kisses tasted of immortality and greatness took flight on winged steeds. Loving Anna was touching a part of him he’d long left behind. Loving her was an innocence he’d never known.” I actually have a pretty high tolerance for flowery prose. You have to be able to endure such stuff if you want to enjoy popular fiction. But even by my lax standards Petersburg’s second half proved too much to bear. Like Phantom, this book had one of the strongest openings I encountered all year, but by the end I was happy to see it go. Which brings us too…

Women’s Rites by Beverly Byrne. This novel came tantalizingly close to being a pop-fiction masterpiece along the lines of The Thorn Birds or Circle of Friends. The author grew up in a working-class family in Revere, MA, and the book seems to draw heavily on her own biography. The two main characters are best friends Barbara Korman and Maria Trapetti. Barbara comes from a family of secular Jews. Maria is an Italian-American Catholic girl who wants to become a nun. Their story begins around 1960, when they are both seniors in the same public high school. Barbie is the slightly more adventurous one. Maria is more serious. Barbie is stunningly beautiful and even before graduating from high school has been recruited by a local agent who wants to make her into a super model. At first Barbie tackles a few local modeling jobs, for Boston-area businesses. But after high school she and her agent head to New York City to try to make it in the big-time world of high fashion modeling. In the meantime, Maria enters a convent, hoping to become a Catholic sister (not a nun; Byrne explains the difference). So far, so good. When drawing on the Massachusetts and New York of her youth, Byrne spins a wonderfully complex plot involving mobsters, gamblers, a priest who breaks his vow of celibacy, a psycho knife-wielding lesbian bent on murder, a white-shoe attorney whose clientele are all mob men, a hasty marriage, a shocking suicide, a five-year-old girl with a scary medical condition, lots of cheesy sex scenes, a woman who improbably produces a bestselling novel, and much, much more. A lot of this is very lurid and melodramatic but those certainly aren’t detriments to a work of pop fiction. For the most part, Byrne is an intelligent and talented writer but every now and then she gets lazy and lapses into clichés and stereotypes (The cabby was small, dark, and wiry – a Hispanic supplied by Central Casting.). But for one dreadful authorial decision, she might have spun her tale into literary gold. Alas, she spun literary bronze instead. Like Maria Trapetti, Byrne spent her youth in Massachusetts and then later moved to New York to try to become a writer. But in later adulthood she divided her time between England’s Isle of Wight and Lanzarote, which is part of the Canary Island chain and governed by Spain. She appears to have written a very good novel about the intersecting lives of Barbie and Maria as they move from girlhood into womanhood, from innocence to experience, shedding careers and vocations and lovers and beliefs along the way. This part of the book is excellent and by itself would have made for a great story. Alas, after creating these two fascinating women and giving them both entertaining story arcs, Byrne must have decided that she wanted to shoehorn her experiences on Lanzarote and the Isle of Wight into their story as well. This was a disastrous decision. She opens the novel with a scene that, chronologically, takes place near the very end of the story. This scene involves a valuable antique that Barbie has stolen from Lanzarote and which a Jesuit priest of her acquaintance is now trying to sell in England while preserving his own and Barbie’s anonymity so that no one connects them to the theft and so that when Barbie gets the money she can make an anonymous donation to a Catholic convent where Maria (no longer a nun) is staying on a retreat. The ridiculous complexity of that description pretty much epitomizes the parts of the novel that deal with the Isle of Wight and (especially) Lanzarote. Every hundred pages or so Byrne brings her thrilling plot to a complete halt for what she calls an “interlude” set on ancient Lanzarote. The first of these interludes covers the years 4000 B.C. thru 375 A.D. in a span of 20 pages. The next interlude spans the years 1733 to 1863 in six pages. These are fairly easy to soldier through. But about 100 pages from the end of the novel, at a point where Byrne really should have brought it to an end (the murderous lesbian has been foiled, Barbie has finally gotten back in touch with the ex-priest who was her one true love and with whom she has a secret love child, and Maria is living with the crotchety but loveable midlist literary novelist who has helped her turn a large, unwieldy manuscript into a soon-to-be commercial success) Byrne instead makes the unfortunate decision to send everybody off to first Lanzarote and then the Isle of Wight for some totally unnecessary and anticlimactic shenanigans involving an old carved idol, the skeleton of a long dead Lanzarote girl, and a whole lot of tedious exposition about the history of the Canary Islands. In the final pages of the novel she returns all the surviving characters to the U.S. and wraps up their stories quickly and way too neatly. By this time the novel has lost all its velocity and the reader is likely to have lost all of her interest. Which is a damn shame. A major part of the novel involves Maria’s efforts to turn that big unwieldy manuscript into an efficient piece of commercial fiction. If only Byrne had done the same thing. Instead she larded her story with unnecessary forays to parts of England and Spain and turned it into an unwieldy mess. A lot of excellent novels fall apart one hundred pages or more before the final line (Of Human Bondage and East of Eden are two that come readily to mind). If that had been the only fault of Women’s Rites (a terrible title, by the way) I might have excused it. But she begins the novel with Lanzarote, and then makes several other needless forays there long before the final one. Byrne is dead now, so it will never happen, but someone could easily make this a much better novel simply by removing Lanzarote from it entirely.

Starting in the Middle by Judith Wax. On May 25, 1979, a DC-10 jetliner known as American Airlines flight 191 crashed just seconds after taking off from Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport. A total of 273 people were killed in the resulting explosion, including all 258 passengers, all 13 crewmembers, and two people on the ground who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. It remains the deadliest aviation disaster on American soil. The crash killed people from many walks of life, but the industry hit hardest was the book business. That’s because the flight, which was bound for Los Angeles, was carrying dozens of people who were planning to attend the American Booksellers Association’s annual four-day trade show there.

One of the passengers on board the flight was 51-year-old Sheldon Wax, Playboy’s managing editor. He’d been with the company since 1960. Accompanying him was his 47-year-old wife, Judith. Hers was a particularly tragic death. A longtime aspiring writer, Judith had put off pursuing a writing career in order to raise the couple’s two children. As the children approached college age, she finally began writing personal essays, and publishing them in a variety of prestigious places, including The New York Times Magazine. Eventually she put together an entire collection of essays about the difficulties of raising a family and managing a mid-life career change. The book, appropriately enough, was called Starting in the Middle. She died shortly before the book was published. Hauntingly, in one of the essays in her book, Wax noted that she tried to pursue a career outside the home when her children were still just eleven and nine years old, but guilt about leaving them for long business trips caused her to develop a number of psychological problems, including a fear of flying. “When the job required travel, I developed such a fear of airplanes my head trembled from takeoff to landing,” she wrote. After quitting the job and returning to full-time mothering, she lost her fear of flying. Curiously, the paperback edition of the book contains a blurb from Erica Jong – “Wise and unfailingly funny.” – who was best known at the time for her debut novel, Fear of Flying. Judith Wax was a smart and sassy essayist. I enjoyed her debut (and only) book. Had she lived she might have become one of the best non-fiction writers of her generation. Alas, we’ll never know. This was a good book and I recommend it.

Downriver by Peter Collier. This is a strong, intelligent, well-written, face-paced and exciting novel. Peter Collier was an avid Berkeley leftist in the 1960s. He and his buddy David Horowitz both wrote for the leftist magazine Ramparts. They began to become disillusioned with the left in the 1970s and by 1980 they were both avid conservatives. Together they co-authored biographies of several famous American family dynasties: The Rockefellers, The Kennedys, The Roosevelts, The Fords, etc. I haven’t read any of those books. After reading Downriver and learning that Peter Collier lived in nearby Nevada City, CA, I was eager to sit down and write him a fan letter. I was hoping I might even be able to visit him in Nevada City some day and talk about his work and his life. Alas, I soon learned that he died in November of 2019, in a Sacramento (my hometown) hospital, just five or six months before I discovered Downriver. Such a shame. This book was promoted by its paperback publisher as a manly but literary adventure novel in the manner of James Dickey’s Deliverence. It sure was that. But it seemed to have an extra something else, that I find it hard to put a finger on. Collier was younger than Dickey. Born in 1939 he wasn’t a Baby Boomer but he was close enough in age that he was able to capture the rebellious spirit of certain young people during the height of the Vietnam War era. I feel guilty not giving this book a Mimsie Award. I think I went into it expecting nothing but an adventurous thrill ride and by the time I realized that this was also a serious literary exploration of various generation gaps, I was nearly done with it. I’ll probably read it again soon, slower this time, and perhaps it will make a future Mimsie Award list. At any rate, I highly recommend it.

Night Woman by Nancy Price. Ms. Price is the author of the much more famous thriller Sleeping With the Enemy, which was made into a hit film starring Julia Roberts. This may have been the worst book I actually finished in 2020. But it was bad in an entertaining way. The plot is completely nutso. It’s the story of Mary Eliot, the wife of a famous American novelist named Randal Eliot. As the story opens Randal has died after losing control of his vehicle in a snowstorm. Soon Mary is approached by a much younger academic who teaches at the same college that Randal once taught at. This young academic (I can’t recall his name and can’t locate my paperback copy of the book, so my recap might be a bit muddled) contacts Mary because he wants to write a book about Randal. Seeing that Mary is in a very vulnerable and fragile emotional state following her husband’s death, the academic decides his best bet is to try to woo her romantically in order to gain access to Randall’s papers, his possessions, even his house. His plan works and soon he and Mary are married. For a long time, whenever he asks about Randal Eliot’s writing process, Mary remains unresponsive, preferring not to talk about it. Finally, after much pestering from the academic, she breaks down and tells him that Randal never wrote a novel. Mary wrote all of his books for him. Randal was an angry alcoholic who talked a lot about the novels he wanted to write but never had the patience to actually sit down and do any writing. Thus (here’s the first real nutso development) we learn that every night after Randal had drunk himself to sleep, Mary would sit down and write a part of novel. In the morning she’d tell Randal that he had dictated this material to her just before falling asleep. Either Randal was stupid enough to believe her or he was just happy to be given credit for her work. At any rate, Mary writes something like five novels in this manner. When she finishes a novel Randal sends it off to his publisher and it soon becomes a Pulitzer-worthy masterpiece that all of America’s literati are gushing over. Randal travels the world, giving speeches, and taking teaching positions at prestigious universities, and generally playing the role of America’s leading man of letters, even though he is incapable of writing a word. Mary has two grown children. They both secretly know that Mary was the real writer of Randal’s novels but neither has any great incentive to reveal this secret. When Mary discloses the truth about Randal to her new husband he is horrified. He believes this disclosure will ruin the book be plans to write about Randal. This struck me as odd, because the truth seems like it would make for a much more sensational book than a straightforward biography of Randal. At any rate, this is a feminist novel in which women’s work is constantly being disparaged by powerful men. After Randal’s death Mary writes another novel, her best yet. She sends it to Randal’s agent and asks him to help her get it published. He responds condescendingly, telling Mary that this latest novel is clearly something that Randal wrote prior to his untimely demise and that she shouldn’t try to take credit for it. Both the agent and Randal’s publisher refuse to have anything to do with the book unless it is published under Randal’s name. Eventually Mary’s new husband becomes so determined to protect the reputation of his hero Randal Eliot that he tries to murder Mary Eliot in order to prevent her from revealing the fact that she authored all of Randal’s books. The premise of the book is crazy but Price at least has the sense not to try to explain it too much. The novel is basically all plot and no introspection. I enjoyed it but I didn’t for a minute believe any of it. I don’t doubt for a minute that women writers have a much harder time getting recognition for their work than male writers do. But it is hard for me to believe that shrinking violet Mary, who basically allows Randal to treat her like dirt, would continue year after year to write undying masterpieces of American literature and allow her abusive husband to take credit for it. If she is smart enough to write brilliant novels she ought to have enough insight into human nature to know that what she is doing is appalling, allowing an evil man with no talent to parade himself before the world as an artist of towering genius. And yet, even after Randal is dead, she immediately allows another horrible man into her life, marries him, and essentially subordinates her every want and desire to his enormous ego and his pathetic desire to bask in the reflected light of Randal Eliot’s greatness. We’re supposed to feel sorry for Mary, but like her second husband I just wanted to push her off a cliff. The story isn’t for a minute believable but I kept turning pages rapidly until the end. Your mileage may vary.

The Cage by Audrey Schulman. This short novel was described by reviewers as a feminist adventure tale. It is the story of Beryl, a photographer who joins an otherwise all-male expedition which is planning to observe polar bears in the far north of Canada and then put together a story about it for National Geographic. The novel was promoted by its publisher as a thriller. I found it less than thrilling. Far too interior for my taste. But it did have some fairly frightening moments. After finishing the novel, all I wrote in my diary about it was “the coldest novel I have ever read.”