Warning: Spoilers Ahead

In my recent review of Ken Grimwood’s 1976 novel, Breakthrough, I mentioned that it bore a resemblance of sorts to Robert Nathan’s classic 1940 fantasy novel, Portrait of Jennie. Grimwood’s novel is about a young woman who, in the 1970s, finds herself, on occasion, magically in the company of a long-dead young woman of an earlier era (roughly the 1860s) whose name is Jennie. Nathan’s novel is about a young man of the 1930s who finds himself, on occasion, magically in the company of a long-dead young woman of an earlier era (roughly the early 1900s) whose name is Jennie. Both books could be categorized as fantasy novels or even ghost stories. Wikipedia notes that Nathan’s novella (it clocks in at about 32,000 words) “combines romance, fantasy, mystery and the supernatural.” You could say the same about Grimwood’s novel, but his tale is much grittier and I would describe it as a sci-fi thriller. Wikipedia also says of Portrait of Jennie, “The most successful of Nathan’s books, it is considered a modern masterpiece of fantasy fiction. Judith Meril called Portrait of Jennie ‘one of the most durable successes in the fantasy business,’ and Ray Bradbury wrote of the book, ‘It touched and frightened me when I was twenty-four. Now, once more, it touches and frightens.’”

When Portrait of Jennie was republished in the 1990s, writer Michael Bishop, who was born in 1945, wrote, “I first read Robert Nathan’s Portrait of Jennie as an impressionable young man of sixteen or seventeen. It appealed to the naïve romantic in me. Reading it thirty-five years later, I note the clean simplicity of its prose, its economical evocations of character and setting, and its unflamboyant wisdom: ‘Yesterday is just as true as today; only we forget.’ Portrait of Jennie reminds us of that truth again. An almost perfect little book.”

When I first became aware of the novel, back in the 1970s, battered copies of it were ubiquitous in old bookstores. The 1948 film adaptation, starring Jennifer Jones and Joseph Cotton, was a mainstay of late-night TV. By that time, it had also been adapted as a radio drama and a stage drama. The story seemed to have lodged itself permanently in the American pop-fiction canon, not to mention the American pysche, along with such ghostly classics as The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and The Raven. But that no longer seems to be the case. Although used copies can still be easily (and cheaply) acquired online, I rarely see it in used bookstores any more. I don’t believe the novel is currently in print in the U.S., except perhaps as an e-book. Amazon.com has both hardback and paperback copies available on its website, but these are old used copies being offered by third-party sellers. While no one was looking, Robert Nathan’s “modern masterpiece of fantasy fiction” became just another lost classic. In another generation or so, it will probably be completely forgotten.

As noted, Portrait of Jennie is a short book. It can be read in two hours or so. I re-read it yesterday for the first time since the 1970s. Honesty requires me to acknowledge that I was no longer much impressed by it. Nowadays, most readers expect their ghost stories to be scary, and Portrait of Jennie isn’t terribly frightening by today’s standards (sorry, Ray Bradbury). The novella also has elements of the gothic romance but, alas, doesn’t have much of an erotic charge to it (unlike Ken Grimwood’s Breakthrough). The story concerns a struggling American artist, Eben Adams, a man in his twenties who is flailing financially in Depression-era New York City. The landscapes and seascapes he paints are not in much demand and no gallery will carry his work. One night, in 1938, he sees a little girl playing hopscotch all by herself near Central Park. He is concerned for her safety and decides to walk her home. She says that her name is Jennie Appleton. Their encounter lasts for just a short while, but something about her haunts his imagination, and he ends up sketching a portrait of her when he returns home to his cheap rented room. A few days later, Eben takes a portfolio of his landscapes to a local gallery and tries to sell some of them to the owner, a kindly man named Henry Mathews. Mr. Mathews doesn’t believe that he can sell any of Eben’s landscapes, but when he comes across the sketch of Jennie, his eyes light up. He gives Eben twenty-five dollars for the sketch (a fortune as far as Eben is concerned) and encourages him to produce more artworks featuring female sitters. Eben finds himself unable to get excited about painting any females other than Jennie. He looks around for her but can’t find her. Eventually, however, he runs into her again while skating on a frozen pond. Curiously, she seems much older now, taller, more poised. Eben tells her that she is his good luck charm, and explains how he sold a sketch of her to Mr. Mathews just as he was nearly out of money. She asks him to paint a full-scale portrait of her, and he promises to consider it. Later, she shows up at his rented room and asks if she can sit for a portrait. He agrees, even though his nasty landlord disapproves of her male boarders having female visitors.

It gradually becomes clear both to Eben and the reader that Jennie is a character out of time. Eben tells a friend, “She has a look of not altogether belonging to today.” Jennie tells Eben that her parents were circus performers, tightrope walkers, who were recently killed in an accident while performing at the Hammerstein Music Hall. Eben does some research on his own and discovers that the people she has identified as her parents died back in 1922, roughly sixteen years before Eben and Jennie met, which seems impossible because Jennie herself doesn’t seem to be much more than a young teenager. What’s more, the Hammerstein Music Hall has been out of business for a decade or more. Jennie is fond of singing a song whose lyrics are:

Where I come from

Nobody knows;

And where I’m going

Everything goes.

The wind blows,

The sea flows –

And nobody knows.

Over the course of a year or two, Jennie will pop up in Eben’s life every few months or so, each time a year or more older than the previous time. She asks Eben to please slow down so that she can catch up with him. He’s not sure what she’s talking about. The reader senses that she is interested in him romantically and wants him to quit aging until she reaches the same age as he is – late twenties.

This is a pretty interesting setup and, eventually, Nathan delivers a decent climax as well – a storm at sea and a devastating tidal wave, followed by a shocking revelation that most contemporary readers probably won’t find all that surprising any more. Alas, the romance isn’t fleshed out enough to be all that compelling. In order to keep Jennie’s true back-story mysterious, Nathan is forced to make her pretty much a complete enigma. It’s difficult to understand why Jennie’s ghost has chosen to become infatuated with, of all people, a failed artist who is more than twice her age when they first meet. The two main characters don’t spend much time together and, in the end, the highlight of their relationship turns out to be just one fairly perfect day in which they share a picnic together. That hardly seems like the stuff of great passion. But I think I can see why the story might have appealed to Ken Grimwood (assuming, that is, that he even read it). With his 1987 novel, Replay, Grimwood essentially invented the time-loop genre which eventually gave us the film Groundhog Day and all of its many imitators – Edge of Tomorrow, Palm Springs, The Map of Tiny Perfect Things, Russian Doll, etc. Portrait of Jennie is a sort of proto-time-loop story. The novel contains a lot of musing upon the idea of stopping time and living out one’s life in the repetition of a single perfect day. At one point, Eben muses: “There is one thing about distance: that no matter how far away it is, it can be reached. It is over there, beyond the Jersey hills – one can drive to it – it is north, among the pines, or eastward to the sea. It is never yesterday, or tomorrow. That is another, and a crueler distance; there is no way to get there. Yet, though I missed her, though I could not reach her, I was not altogether without her. For I found that my memory had grown sharper; or else it was beginning to play tricks on me. It was not so much that I began to live in the past, as that the past began to take on more and more the clarity, the actual form of the present, and to intrude itself into my daytime thoughts. The present, on the contrary, seemed to grow a little hazy, to begin to slip away from me…so many things reminded me of her. And then I would be seized by memory so urgent that what I remembered seemed almost more real to me than what was before me. Where others dreamed ahead that spring, toward the summer, I dreamed backward into the past.”

At one point Jennie tells Eben that, “Tomorrow is always.” Later he decides that, “Yesterday is always, too.” The whole book seems to argue that yesterday, today, and tomorrow are all essentially the same day – and, if you want, you can live inside one perfect day for the rest of your life. Nathan wasn’t clever enough to make the storytelling breakthrough that Grimwood made in Replay. It didn’t occur to him to create an actual time loop for Eben and Jennie to live inside of forever. But his story seems to argue that love itself is a sort of metaphorical time loop that holds lovers together even when they are far apart, separated by a great distance, or even by death. Grimwood would later take that metaphor and turn it into a device that has since become a mainstay of contemporary fantasy literature – the time loop. When a scholarly book is produced on the origins and evolution of the contemporary time-loop story, I doubt that Portrait of Jennie will be mentioned as an early progenitor of the genre. But, though I can’t even prove that he ever read it, I believe that it had some influence on Ken Grimwood. But the evidence isn’t to be found in Replay but rather in Grimwood’s first novel, Breakthrough, published more than a decade earlier. Breakthrough’s plot, which features the protagonist’s intermittent interaction with a dead woman of an earlier era, a dead woman named Jennie, suggests to me that, even in the 1970s, Grimwood was being influenced by Nathan’s fantasy masterpiece. Portrait of Jennie seems to be rapidly fading from the public consciousness. Nowadays, few people under the age of sixty are probably even aware of the book. But even if the book should become completely forgotten at some point, a piece of it will live on every time a new iteration of the time-loop story makes its way into print or onto the big screen or the small screen. Robert Nathan may not have originated the time-loop story, but Jennie Appleton seems to have been at least a partial inspiration to Ken Grimwood, the man who did invent the time-loop genre.

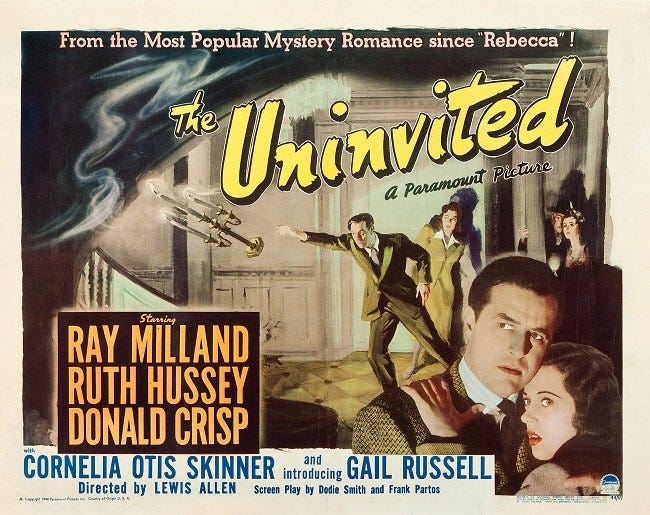

But even before Nathan influenced Grimwood, he appears to have influenced an earlier generation of writers as well. The years after the publication of Portrait of Jennie brought the publication of numerous ghostly romances, including Dorothy Macardle’s 1941 novel Uneasy Freehold, the source of the 1944 film The Uninvited, and R.A. Dick’s 1945 novel The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, which was adapted by Hollywood in 1947. Wikipedia notes that The Uninvited was “part of a cycle of supernatural-themed films that began appearing in the mid-1940s.” Some have attributed this phenomenon to the success of Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 gothic novel, Rebecca, and the 1940 Alfred Hitchcock film it inspired. But Rebecca is not a true ghost story. At the time that films like The Uninvited and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir were going into production, Portrait of Jenny was the bestselling ghost story in America, and had been for several years. Robert Nathan, who died in 1985, isn’t widely remembered any more. But he lives on as a ghost who dwells in the many books and films that seem to owe a little something to Portrait of Jennie.

Good book and better movie. Read it forty years ago.