NOTE: This is an extended version of an essay that appeared in Quillette back in February.

Next year, on the fiftieth anniversary of the film’s release, the media are likely to bring us countless think pieces on Steven Spielberg’s Jaws. Among other things, it will be hailed as the film that invented the summer blockbuster, the first great film to be directed by a baby boomer, the first great film to be shot largely on the ocean, and the first great film in which the musical score was practically a major character. The film significantly altered the way that Hollywood would henceforth promote films (heavy TV advertising), and it caused studios to seek out numerous similar projects – i.e., high-concept action films that often included non-human monsters (the following years would bring us Dino DeLaurentiis’s King Kong remake; a 1977 Jaws rip-off called Orca; Irwin Allen’s 1978 dud The Swarm, which tried to do for killer bees what Jaws did for great white sharks; and Ridley Scott’s 1979 blockbuster, Alien, which was essentially “Jaws In Space”). But before Jaws became forever associated with the name Steven Spielberg, it was a hugely successful novel written by Peter Benchley. Nowadays, the film is still highly regarded while the novel is, if not forgotten, no longer much appreciated. Some younger people, encountering a copy of the novel in a used-book store, probably assume that it is a mere novelization of the film (which is true of the novel Jaws 2, by Hank Searls).

Jaws, the novel, was published on February 1, 1974. It celebrates its fiftieth birthday this year, although the celebration isn’t likely to be terribly extravagant. Benchley died in 2006, at the age of 65, and his cultural status is nowhere near as great as Spielberg’s. His biography is also quite different from Spielberg’s. Spielberg is a Jew who grew up primarily in Phoenix, Arizona. A mediocre school student, he dropped out of Cal State Long Beach in the late 1960s and very quickly established a reputation as a cinematic wunderkind. In 1968, when he was only twenty-one years old, Spielberg signed a seven-year contract to work as a director for Universal Studios. Benchley, born six years before Spielberg, in 1940, came from a New England family that had been in America since its days as a British colony. His ancestors were largely members of the so-called “frozen chosen,” stiff-necked WASPs who were prominent in government, business, and society. Peter’s great-great-grandfather, Henry Wetherby Benchley (1822-1867), served as Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts and helped found the Republican Party. He was a devout abolitionist who was arrested and jailed in Texas for helping slaves escape via the so-called Underground Railroad. Peter’s grandfather was Robert Benchley, a co-founder (along with pals such as Dorothy Parker and George S. Kaufman) of the famous Algonquin Roundtable. Robert Benchley became one of the New Yorker’s first breakout stars, publishing roughly a column a week for that magazine throughout the 1930s. Robert wrote for both the Broadway stage and for the Hollywood cinema, and would eventually become a prominent comic character actor, usually playing drunks and/or pompous buffoons in dozens of motion pictures, including such famous fare as The Gay Divorcee, Foreign Correspondent, and I Married a Witch (see photo below).

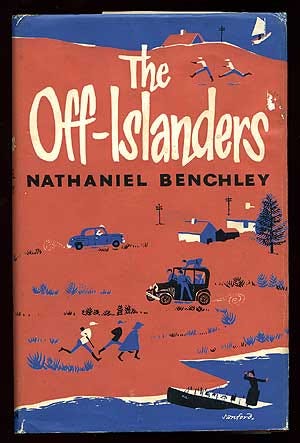

Peter’s father, Nathaniel Benchley, also a successful writer, penned everything from naval thrillers to children’s books. His 1961 novel, The Off-Islanders, was made into the hit 1966 film The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming. Directed by Norman Jewison, it was the sixth highest-grossing film of the year and was nominated for a Best Picture Academy Award. In October of 1975, while Jaws was still gobbling up dollars at the international box office, ABC TV broadcast a movie called Sweet Hostage, starring Martin Sheen and Linda Blair, which was based upon Nathaniel Benchley’s 1968 novel, Welcome To Xanadu. The film received middling reviews but was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Television Mini-Series or Movie and has since become a sort of Holy Grail for fans of 1970s made-for-TV films.

Peter, like his father and grandfather before him, matriculated at both the exclusive prep school Phillips Exeter Academy and at Harvard University. He was what would nowadays be termed a “nepo baby,” someone who made good in a desirable profession at least in part because he was born with good connections in said profession. A 1974 New York Times story describes Benchley’s early career like this:

“As a third‐generation member of a literary dynasty, with only a first name to make for himself, it had never occurred to Peter Benchley to be anything but a writer. He had started trying to market his work when he was 16, and had sold his first short story to Vogue when he was still in his teens. He acquired an agent, Roberta Pryor of International Famous Agency, when he was 21. Another I.F.A. agent represented Peter's father, Nathaniel, the author of numerous navels [sic] and juveniles, and Mrs. Pryor took Peter on a “will you do my kid a favor” basis. He worked briefly at The Washington Post, pounding out three‐paragraph obits like all beginners, and moved to Newsweek, where he wrote his first piece on sharks in 1965.”

To give you an idea of how well-connected Benchley was, I have in my book collection a copy of his 1986 novel Q Clearance inscribed by hand to “Kim & Polly Roosevelt – from Baby Boy Benchley up the Bluff.” (As a child, Benchley summered in the small Nantucket village of Siasconset, just a short walk away from where Theodore Roosevelt’s grandson Kermit “Kim” Roosevelt and his wife spent many of their summers.) Peter’s first book, a travel memoir called Time and a Ticket, was published in 1964 and vanished immediately into obscurity. In 1967 he became a speechwriter for President Lyndon Baines Johnson, a gig that later inspired Q Clearance but which ended abruptly when Johnson opted not to run for re-election in 1968. By the early 1970s, Peter and his wife and their two young children were living in a house in Pennington, New Jersey. For fifty dollars a month, Peter rented a small office space above a furnace supply company, where he did most of his writing. At this point he was struggling to make ends meet by doing freelance writing for The National Geographic and other magazines.

Considering both his degree and his pedigree, Peter wasn’t likely to starve any time soon, but the 1970s were a financially unfriendly decade, and even many Harvard graduates had to struggle to make a living. Thanks to his famous last name, Peter caught the attention of Tom Congdon, who was then a senior editor at Doubleday, a major American publishing house. Congden asked Peter to meet him for lunch in New York City and pitch him some book ideas. On June 14, 1971, the two men met at a restaurant called Clos Normand and (over a seafood meal, appropriately) Peter pitched an idea for a nonfiction book about sea pirates. Congdon was lukewarm on the idea. On a whim, as the lunch drew towards a close, Congdon asked Peter if he had ever thought of writing a novel. Peter mentioned an idea he had been nurturing. Congden told Peter to go home and write a one-page description of his book idea. Here’s the New York Times again:

On June 23, Benchley's one‐page description arrived. “Suppose a Long Island resort community was suddenly visited by a great white shark? A young woman is killed. . . . How does the community cope with this inexplicable menace?”

The editorial board liked the idea and made an offer to Benchley’s agent. Doubleday would pay Benchley $1,000 to write up the first four chapters of a novel based on his one-page synopsis. If Doubleday liked the first four chapters, Benchley would be permitted to continue with the novel and eventually receive an additional $6,500 upon its completion. If Doubleday didn’t like the first four chapters, the project would be abandoned and Benchley would be expected to return one half of the $1,000 advance, keeping the rest for himself (minus the ten percent his agent would receive). Benchley’s agent, Roberta Pryor, balked at this offer. She didn’t believe that Peter should have to return any of his $1,000 advance if Doubleday passed on the book. Nowadays it’s hard to fathom, but that $500 dispute between agent and publisher very nearly sank the project even before it was launched. Doubleday argued that it would be setting a dangerous precedent by allowing authors to keep the entire amount of their advances on books that the company ultimately decided not to go forward with. But Pryor wouldn’t budge. She told the New York Times: “For me it was the principle of the thing. Are they in the risk business or not? You want the publisher’s vote of confidence, not the money on a yo-yo.”

Jaws would eventually become a multi-million dollar entertainment-industry juggernaut but, for several weeks in 1971, the entire project hung in limbo because of a dispute over a mere $500. Fortunately, Doubleday finally relented. Benchley was told that he could keep the entire $1,000 if he turned in the first four chapters by April 15, 1972. On March 20, 1972, twenty-five days ahead of his deadline, Benchley turned in the 174 pages that comprised the first four chapters of a manuscript that he had titled A Stillness in the Water. The opening chapter read pretty much as it would eventually appear in the published novel. A pretty young woman takes a midnight swim in the waters off Long Island and is killed by a massive shark. Much of the chapter is told from the shark’s point of view and rendered with scientific explanations of how sharks hunt and feed, which gave the killing a cold and clinical quality that was at odds with the horrific human tragedy it described. The editorial board at Doubleday loved it. Alas, the next three chapters were not at all what they were expecting.

Benchley’s father and grandfather were satirists and wrote primarily in a comic vein. Nathaniel’s The Off-Islanders, though it dealt with a Cold War confrontation between a New England fishing village and the Soviet submarine crew that washes up on its shores, was more interested in providing humorous social commentary on the resultant culture clash than in delivering thrills and chills. Peter took a somewhat similar approach in the first 174 pages of his shark novel. After that short and thrilling opening chapter, he focused primarily on the ways that the unseen menace offshore turns a peaceful little fishing hamlet into a veritable cuckoo’s nest of erratic human behavior, with neighbor turning against neighbor, and various self-appointed champions of the public welfare coming up with cockamamie schemes to either kill the shark or use its presence as a boon to attract more tourists. One can easily imagine actor Paul Ford’s Fendall Hawkins character (the ex-military man, determined to fight the commies in The Russians Are Coming…) and Brian Keith’s Police Chief Link Mattocks (the level-headed voice of reason in the same film) fitting comfortably into a book like A Stillness in the Water. But Tom Congdon wasn’t interested in a retelling of The Off-Islanders that featured a shark instead of a Soviet sub. He wrote to Pryor:

“There is no question but that Peter Benchley's material is conscientiously wrought…I'm not entirely sure, however, that it's successfully wrought…I find the opening of the book marvelous, and the shark scenes good almost all the way through. But almost everything else seems pretty mild. . .” Congdon objected that the main character, the police chief who decides to close the beaches after the shark strikes, was constantly cracking corny jokes. “The author is seeking both chuckles and gasps of horror,” he wrote, “and it just doesn't seem to be working. You just can't graft light humor onto a gory five‐death tragedy. . . . I find the narrative unfolding pretty limply and uncertainly . . . there are lots of small confusions. . . the shark scenes, though powerful at first, get repetitive.”

To his credit, Benchley never bridled at any of the many editorial suggestions and rewrite requests that came to him via Congdon or from the book’s co-editor Kate Medina. He told the New York Times, “When they insisted, I gave in. They’ve been in business a long time, and I’d never written a novel.” (After the book became a monster success, Benchley mentioned his editors Medina and Congdon in an interview he gave to Publishers Weekly. Congdon took offense, insisting that he was its sole editor and that Medina had worked on the book only as a “consultant.” PW eventually ran a correction.)

At this point in his career, Benchley still thought of himself as a non-fiction writer. The shark book was something he undertook out of financial necessity. This isn’t to suggest that Jaws is a piece of hackwork. It isn’t. Benchley obviously took a great deal of care with the novel. His willingness to repeatedly alter the course of his book at the suggestion of his publisher, editor, “consultant,” etc., seems less like the behavior of a literary hack than simply a survival strategy for a thirty-something family man struggling to pay his bills. It also suggests humility. As the 1970s progressed, Benchley proved himself to be the rare American bestselling author who always managed to keep his ego in check. Horror stories abound about the monomaniacal behavior of Erich Segal, Richard Bach, Harold Robbins, Leon Uris, and other schlockmeisters of the era. But Benchley always managed to come across in TV interviews as polite and humble. Even during the researching of this piece, I couldn’t find anything online suggesting that Benchley was anything other than a decent human being with his ego well in check. Over the years, plenty of harsh criticism of his novels has made it into print, but apparently no one ever had anything bad to say about the author.

At any rate, by April 28, 1972, Benchley had amended the opening chapters sufficiently for Congdon to formally offer him a publishing contract. As noted, he would be paid a total of $7,500, which included the $1,000 he had already received for writing the first four chapters. He would get $2,500 as soon as he signed his contract, another $2,000 upon delivery of a first draft, and $2,000 more when the final manuscript had been accepted. That $7,500 may not sound like much, but in inflation-adjusted dollars it would come to roughly $55,000 today. That kind of money wouldn’t turn the head of a contemporary bestselling author like Stephen King or John Grisham, but almost any first-time novelist would probably be thrilled to get it. And as soon as paperback publishers and movie studios began bidding on the rights for the novel, Benchley would find himself awash with wealth.

But, as the Times noted, even after the contract was signed, “Congdon continued to send Benchley a stream of editorial suggestions – don’t spell out things too much, less is more, don’t be too predictable, keep a tight time frame. Benchley remained patient and pliable. Congdon gratefully wrote Roberta Pryor on June 1, ‘Peter was gracious enough not to sputter at anything I suggested.’”

At one point Benchley’s book included a sex scene between Martin Brody (played by Roy Scheider in the film) and his wife Ellen (Lorraine Gary) but Congdon nixed it, telling Benchley, “I don’t think there’s any place for wholesome married sex in this kind of book.” Obligingly, Benchley got rid of the sex scene and created a less wholesome sexual relationship between Ellen and the young ichthyologist Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfus).

On January 2, 1973, Benchley finally turned in his completed manuscript. Congdon and Doubleday were thrilled with it, which makes sense, considering that they pretty much dictated it to him. Nonetheless, it was Benchley who wrote every word of the novel. The story was based on his own original idea. Growing up in Nantucket, he had developed a keen interest in sharks, and it was that near-obsession with the creatures that infused the novel with so much awe and terror. The only thing that Congdon didn’t like about Benchley’s book was the title: A Stillness in the Water. He said it sounded like, “a Francoise Sagan novel about a young woman who goes to the Riviera to forget about an unhappy love affair.” Congdon suggested, The Summer of the Shark, but Benchley warned him that such a title might get the book shelved in the nature sections of American bookstores. According to Congdon, a total of 237 titles were suggested and shot down, including The Terror, The Monster, The Year They Closed the Beaches, The Leviathan, and even The Jaws of the Leviathan. Days before the book was scheduled to be sent to the printers, Congdon and Benchley met for lunch in New York to try to agree on a title. By this time they were getting desperate. At one point, Benchley said, “Why not just ‘Jaws,’” and instantly Congdon knew that they had finally found the title they had been looking for. But they still had a few problems to solve.

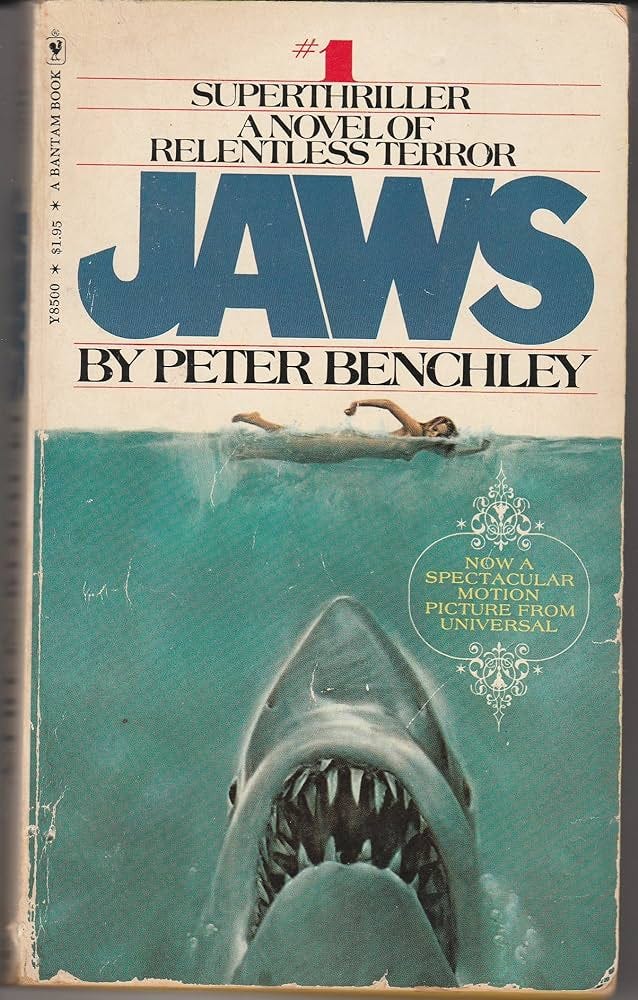

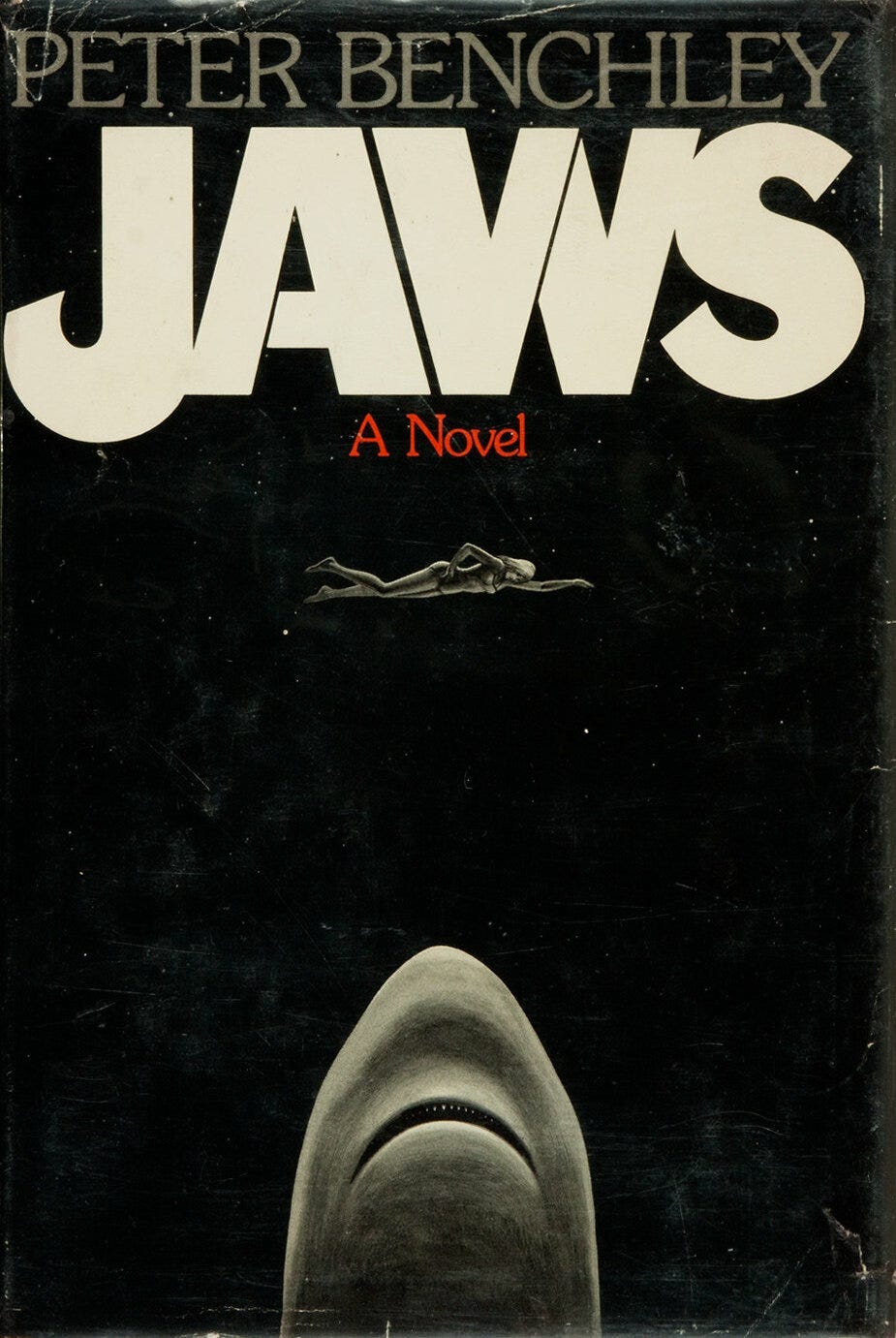

Originally, Benchley had wanted the cover of the book to feature a bucolic Long Island beach town as seen through the mouth of a shark, jagged teeth framing the image from above and below. A mockup of the cover was made but Doubleday’s sales force, the men who would fan out across the country and try to sell the book to American bookstores, objected to it. Curiously, it reminded them of vagina dentata, a folk tale about a woman with a vagina that contains teeth (and a sharp bite). Congdon asked his art director if the cover could simply contain a shark rising towards the surface of the sea. His art director vetoed the idea, telling Congdon that the cover wasn’t big enough and that the fish would look like a sardine. Desperate, Congdon opted for an all black jacket cover that would simply feature the word Jaws upon it. But the salesmen hated it, protesting that it looked like a book about dentistry. At that point Doubleday turned to legendary book-cover artist Paul Bacon, who resurrected the rising-fish motif, but this time he added a woman swimming on the surface of the water. This helped to illustrate the giant scale of the shark and also suggested the menace that was to be found in the book’s plot. Congdon told the New York Times that everyone at Doubleday realized that the new fish image “looked like a penis with teeth,” but no one had any problem with that. Apparently, penises with teeth were acceptable but vaginas with teeth were beyond the pale (the paperback edition leaned into the sexual imagery by making the female swimmer clearly young and naked and the shark clearly voracious, each tooth a menacing phallus of its own). At any rate, the book now had a title, a cover, and was ready to be unleashed upon the American reading public.

While all of this bickering over the cover and the title were going on, Doubleday’s subsidiary rights department was busy negotiating with paperback publishing houses and subscription services. The book was sold to The Book of the Month Club, a subscription service that mailed out cheaply-made and discounted copies of newly published books to its tens of thousands of subscribers weeks before the publication date of the regular hardback. Those subscribers could opt to either buy the book or send it back unread. A BOMC presale usually boded well for a new book’s marketability. Likewise the book was presold to the Reader’s Digest Condensed Book Club and to the Playboy Magazine Book Club, both of which were subscription services. These sales made the book profitable even before it hit the nation’s bookstores. And the money they brought in was split with the author.

Oscar Dystel, the president of Bantam Books, a paperback imprint, was reading a pre-publication copy of the novel on the commuter train home from his office in New York City one evening and became mesmerized by it. The only thing he didn’t like about it was the author’s name. This is the one time when being a nepo-baby might have actually hampered the author of Jaws. “Peter Benchley – that turned me off,” Dystel told the Times. “The name stood for humor, a certain lightness of tone; the incongruity might have been negative. Still, the authenticity came through. He seemed to be writing out of his own experience.”

Shortly after reading the book, Dystel instructed Bantam editor Alan Barnard to offer Doubleday $200,000 for the paperback rights to Jaws. It was a huge amount of money and the executives at Doubleday were torn. They worried that if they turned down the offer, they might never get another one as good. But they also thought it was possible that if they put the book up for auction – i.e., allowed all the top paperback publishers to bid in real time for the reprint rights – they might be able to get more money, possibly even as much as $250,000 or $300,000. Eventually, they opted to put the book up for auction, but they offered Bantam the right to top the winning bid if it chose to do so. As a result, Bantam ended up securing the paperback rights for the curious (but astounding!) figure of $575,009. Doubleday got half of that money. The other half went to the author. Roberta Pryor sold the film rights to producers David Brown and Richard D. Zanuck for $150,000. She secured Benchley another $25,000 for writing the script (eventually he would share screenwriting credit with Carl Gottlieb, who was brought in to “to do a dialog polish” on Benchley’s script; Benchley noted wryly that describing Gottlieb’s rewrite as a dialog polish was like “referring to gang rape as heavy necking.”). According to The Jaws Log, a nonfiction account of the Jaws phenomenon written by Gottlieb (whose relationship with Benchley was cordial despite the above gang-rape joke), Peter Benchley had a grand total of $600 left in his bank account on the day that the paperback sale to Bantam was finalized.

On January 18, 1974, an article in Publishers Weekly noted that, “Peter Benchley has written a major novel, one that has created virtually unprecedented prepublication excitement…Over $1 million in subsidiary rights sold; 35,000 initial printing, major ad-promo.” By mid-March, Doubleday had printed up 75,000 copies of the novel and it was selling roughly 8,000 copies a week. By today’s standards 8000 copies a week may not seem like much, but the literary marketplace was a lot different back in 1974. For one thing, the population of the U.S. was lower by 120,000,000 people. Furthermore, books were sold differently. Nowadays you can buy hardback books at your local grocery store, national supermarket chains like Wal-Mart, membership-only chains like Costco and Sam’s Club, in airport gift shops, and of course online. Back in 1974 almost all hardback book sales in America took place in bookstores. And most of those stores were small, local independent shops. Large chain bookstores such as B. Dalton’s and Waldenbooks existed back then, but they didn’t have anywhere near the reach that they would eventually attain in the final decade of the twentieth century, just prior to the advent of Amazon.com. Thus, in order to buy a copy of Jaws in 1974, the consumer had to make a special trip to his local bookseller’s shop. Hardbound books were marketed almost exclusively to Americans who earned well above working-class wages. Jaws was priced at $6.95 in 1974, the equivalent of nearly $45 today. John Grisham’s latest hardback is currently selling for $19 at Amazon, marked down from the publisher’s list price of $29.95. And hardback books were almost never discounted by the retailer back then. The evidence suggests that a lot of those early copies were purchased by people who were not regular bookstore customers. Television had much to do with this. Benchley was a tall, handsome, erudite, and witty individual. Doubleday recognized this and booked him on as many talk shows and morning news programs as possible. But Jaws was also one of the few novels of the era that was advertised on TV directly to the consumer. According to the Times, “[Doubleday] Advertising manager David Cathers knew that Jaws had broken out of the hardcore market of people who regularly go into book stores, which he estimates at roughly 60,000, and was reaching an audience that seldom buys hard-cover books. He scheduled some TV spots to supplement newspaper ads. He figured that the total advertising campaign for Jaws would cost between $50,000 and $60,000.”

In Bestsellers, a book about the popular fiction of the 1970s, scholar John Sutherland dedicated an entire chapter to Jaws. It begins: “The term is often used loosely, but Jaws is a true superseller of the 1970s. In just six months as a Bantam paperback it sold over six million copies, and within a couple of years had come up to the maximal ten million mark. In Britain, Pan’s paperback sold a million in its first year and almost twice as many in its second, boosted by the film.” Sutherland links the novel to two other massive bestsellers of the era. He writes, “The 1970s have been notable for a number of bestselling animal narratives directed at an adult rather than the traditional young persons’ market. Three of them have been supersellers: Jonathan Livingston Seagull [written by Richard Bach], Jaws, and Watership Down [by Richard Adams]. Oddly enough, all three have been by authors previously unknown to the mass reading public.” Chapter Three of Grady Hendryx’s seminal 2017 study Paperbacks From Hell: The Twisted History of 70s and 80s Horror Fiction, is titled When Animals Attack and begins with a discussion of both Jaws and Watership Down, although, amusingly, Hendryx inadvertently credits the authorship of the latter novel to Richard Harris (his confusion was probably due to the fact that actor Richard Harris was the star of the abysmal 1977 Jaws wannabe Orca). I would also link Jaws to Mario Puzo’s The Godfather and William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, two other massive bestsellers that, like Jaws, were very loosely based on actual events and which became much better films than they were novels, with screenplays written or co-written by the author of the novel (Puzo and Blatty both won Oscars for their screenplays; Benchley wasn’t even nominated). Jaws had been in print for less than two years when Alice Payne Hackett and James Henry Burke published their survey of American book sales, 80 Years of Bestsellers, but it had already managed to become the seventh bestselling novel of the twentieth century, behind only The Godfather, The Exorcist, To Kill a Mockingbird, Peyton Place, Love Story, and Valley of the Dolls – all of which had been in print years before Jaws was published.

People who are familiar only with the movie might be surprised to discover that, as Sutherland put it, “Jaws film and Jaws novel are significantly different.” According to Spielberg, the final script contained 27 scenes that appear nowhere in Benchley’s book (most notably, Robert Shaw’s monologue about the sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis during WWII). Benchley’s book, on the other hand, contains several subplots that Spielberg opted not to use in his film. In the film, Mayor Larry Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) pressures Police Chief Brody to keep the beaches open for financial reasons only. He worries that the small businesses of Amity will suffer if the shark is allowed to keep tourists from swimming off the shores of the small community (in the film, Amity is a New England town; in the book it is situated in Long Island, New York). But in the book Mayor Vaughan (in the film, for some reason, his name is spelled Vaughn) has an even stronger incentive for keeping the beaches open. Long Island (as readers of The Godfather learned a few years before Jaws was published) is where many of New York’s top mafia leaders reside with their families. Years earlier, when Vaughan’s wife was sick and he didn’t have the money to pay for her medical treatment, he accepted a financial “gift” from a prominent Long Island mobster. That mobster has since made significant investments in Amity’s real-estate market, and he worries that the value of his holdings will plummet if Vaughn allows the beaches to be closed. The mob is putting pressure not only on Mayor Vaughan but also directly on Brody. At one point, a couple of thugs drive up to Brody’s house and murder the family’s cat right in front of one of Brody’s children. This mafia subplot adds to Chief Brody’s woes. When Brody finds the dead cat in the garbage can, Benchley goes into full horror mode: “Lying in a twisted heap atop a bag of garbage was Sean’s cat – a big, husky Tom named Frisky. The cat’s head had been twisted completely around, and the yellow eyes overlooked its back.”

As mentioned, the book also contains a sexual flirtation between Ellen Brody and Matt Hooper that never made it into Spielberg’s film. In fact, Ellen’s dissatisfaction with her life is a prominent subplot of the novel. Ellen was raised in the East Coast’s upper class and educated at Miss Porter’s School (an elite prep school whose alumnae include Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Gloria Vanderbilt, as well as the fictional Sally Draper of Mad Men) and at Wellesley (though she dropped out after her junior year to marry Martin who, five years older than she, was already a member of the Amity Police Department). As a child she merely summered at Amity. Martin, on the other hand, was born and raised among Amity’s working-class full-time residents. Now that she is married to a townie, Ellen’s old friends tend to pity her and to look down on her husband. This puts a lot of stress on the Brodys’ marriage, a subject that isn’t given any consideration in the film. But Benchley spells it out in detail:

She hated her life, and she hated herself for hating it. She thought of a line from a song Billy [her son] played on the stereo: “I’d trade all my tomorrows for a single yesterday.” Would she make a deal like that? She wondered. But what good was there in wondering? Yesterdays were gone, spinning ever farther away down a shaft that had no bottom. None of the richness, none of the delight, could ever be retrieved…She walked across the street and climbed into her car. As she pulled out into the traffic, she saw Larry Vaughan standing on the corner. God, she thought, he looks as sad as I feel.

In the film, Vaughn is largely a cartoon villain and Ellen just a cardboard-cutout of a housewife. Neither is given much weight, or any backstory. And Spielberg was right to go in that direction. Nobody who queued up an hour before show time to see Jaws in a theater back in 1975 did so because they wanted to watch the sorrows of an everyday housewife or a shady politician. Those moviegoers (and I was one of them) wanted to see a monster shark doing monster shark stuff. They wanted to see three men in a small boat doing battle with a largely unseen terror from the depths of the ocean.

It would be madness to remake Spielberg’s original film. It is already perfect. But some Hollywood producer ought to consider creating a limited TV series that faithfully retells the story of Benchley’s novel from the perspective of Ellen Brody. Just as Universal Television rebooted the Psycho franchise with a TV series (Bates Motel, which ran on A&E from 2012 to 2017) that retold the story of murderer-and-taxidermist Norman Bates largely from the perspective of his mother (who is never seen alive in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film), a TV series focused primarily on Ellen Brody might be able to fathom depths of the Jaws story left unexplored by Spielberg in his 1975 film. Perhaps the series could jump back and forth between the perspectives of Larry Vaughan (who is a sympathetic character in the novel) and Ellen Brody.

Another aspect of Benchley’s novel that Spielberg mostly ignored is the economic struggles of the people of Amity. The 1970s were a decade marked by stagflation. After decades of growth, wages began to flatten out in the 1970s. Union membership stopped growing. Inflation began to rise. An oil embargo by OPEC caused gas prices in America to rise astronomically. Martin Brody and the other residents of Amity are always worrying about money. Benchley writes, “Like the rest of the country, Amity was feeling the effects of the recession…Like all their friends on tight, fixed incomes, the Brodys shopped according to the supermarket specials. Monday’s special was chicken, Tuesday’s lamb, and so forth through the week. As each item was consumed, Ellen would note it on her list and replace it the next week…Thursday’s special was hamburger, and Brody had seen enough chopped meat for one day.”

All this talk about meat isn’t random. For many American families, meat became a luxury in the 1970s. A recent article in the New York Times had this to say about meat prices in the early 1970s: “The price of beef was so high by then that boycotts and protests were organized against grocery stores. In the opening sequence of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Mary Richards famously rolled her eyes at the label of a meat package before tossing it into her cart. By 1973, Curtis Mayfield sang in ‘Future Shock’ about ‘the price of the meat / Higher than the dope in the street,’ and President Richard M. Nixon had announced government price ceilings on beef.”

The Times piece quotes Joshua Specht, a professor of history at Notre Dame and the author of Red Meat Republic, on how meat prices affected the American family man in the 1970s: “That is a time when there’s a breakdown of a certain kind of manhood and a certain kind of economic man. There’s a phase change in the economy, and that coincides with a change in the place of the male breadwinner. To be a successful man is to eat steak. And that breaks down in the ’70s.”

In the novel, when a fisherman named Ben Gardner is killed by the shark (his severed head provides the first huge jump scare in the film), Martin’s first concern is for Ben’s widow, Sally. He tells Ellen, “I worry about her. Have you ever talked to her about money?”

Ellen says, “Never. But there can’t be very much. I don’t think her children have had new clothes in a year, and she’s always saying that she’d give anything to be able to afford meat more than once a week, instead of having to eat the fish Ben catches. Will she get social security?”

Although meat isn’t affordable for many of the Amity residents in Jaws, it is well within the means of the well-off New Yorkers who, when news of the giant shark becomes widely publicized, begin to make day trips to Amity hoping to catch a glimpse of the sea monster. Rose Loeffler, who runs a butcher shop with her husband, tells him at the end of a busy workday, “Eighteen pounds of bologna! Since when have we ever moved eighteen pounds of bologna in one day?”

Her husband, Paul, tells her, “Roast beef, liverwurst, everything. It’s like everybody from Brooklyn Heights to East Hampton stopped by for sandwiches.”

Meat and manhood were inextricably intertwined in 1970s America. Benchley, a married family man at the time, understood this on a personal level. Spielberg, a young, childless bachelor, probably didn’t notice it much. Spielberg’s film occasionally gestures towards the financial precariousness of some of his characters, but the fact that he chose to shoot his film on Martha’s Vineyard, then as now one of the priciest housing markets in America, tells you that he really wasn’t interested in the lives of America’s working stiffs to the degree that Benchley was. The novel Jaws is rooted in a specific location (Long Island) and socio-economic milieu (the working class) and time (the 1970s). The film, like many of the movies that bear Spielberg’s imprimatur (E.T., Close Encounters, Poltergeist, The Goonies, The Gremlins, etc.) is set in a fantasy version of Middle America where people occasionally complain about a lack of money or the bad economy but are more or less immune from the effects of these things. Spielberg’s film could just as easily have been set in the 1950s, 1960s, or 1980s.

In the novel, when Martin Brody, Matt Hooper, and old man Quint go to battle against the shark, they are striking a symbolic blow for American manhood. Cheap fish in the form of frozen fish sticks, McDonald’s Filet-O-Fish sandwiches, and tuna casseroles began to proliferate in working-class American diets during the inflationary 1970s. And, like Sally Gardner, many Americans weren’t thrilled about this. If only subliminally, Benchley’s book struck a blow against these cut-rate piscine meals. In the novel (spoiler alert!) only one man survives the battle between man and sea monster. That man is Martin Brody, the only one of the three shark hunters who is married and has a family to feed. What’s more, Martin dislikes the ocean. He’s a landlubber and a red-meat kind of guy. The ending of the novel leaves no doubt that he has earned the right to put meat on his family’s table for years to come. (Film critic Neal Gabler has noted that Hooper represents the scientific approach to solving a problem, Quint represents a spiritual approach, and Brody represents an old-fashioned commonsensical approach; and it is Brody’s approach that ultimately bears fruit). A TV reboot of Jaws, set in the immediate aftermath of the recession that began in 2008, could add poignancy to the story that the film lacked.

Nowadays, it may seem odd that Spielberg’s film ditched so much of the story contained in Benchley’s novel. Contemporary films based on monster bestsellers generally strive to be as faithful to the books as possible, lest they provoke the wrath of hardcore fans of the fictive worlds of George R.R. Martin, Suzanne Collins, Stephanie Meyers, J.K. Rowling, or some other mega-bestselling author. Despite the fact that she possesses two of the most beautiful greenish-blue eyes in filmdom, Kristen Stewart was required to wear contact lenses in the Twilight film series so as not to upset fans of the books who knew that Bella Swan possessed eyes of “chocolate brown” (until, spoiler alert, she becomes a vampire and then her eyes turn reddish). But that kind of cinematic fidelity to a film’s literary source is a fairly recent phenomenon. For instance, Three Days of the Condor, which was the seventh highest grossing film of 1975 (Jaws was number one), was based on a James Grady novel called Six Days of the Condor. The filmmaker, Sidney Pollack, ditched much of the book’s material in order to make his film tighter.

If they think of him at all any more, pop-fiction fans probably remember Peter Benchley as a one-book wonder. But that isn’t quite fair. It might be more accurate to think of him as a one-decade wonder. He cranked out two more monster bestsellers before the end of the 1970s. The Deep was the fourth bestselling novel in America for the year 1976 and was adapted into a successful 1977 film by director Peter Yates. The Island was the fourteenth bestselling novel of 1979 and was adapted by Michael Ritchie into a 1980 cinematic flop. After that Benchley was never much of a pop-cultural force at all. He published five more novels between 1982 and 1994, but none of them became huge sellers. Like John Denver, The Bee Gees, and Olivia Newton-John, he was never again as big as he had been in the 1970s. But, as pop-fiction experts John Sutherland and Grady Hendryx have pointed out, Benchley’s Jaws inspired a lot of imitators. He may not have produced a lot of thrillers himself, but he blazed a trail for plenty of them. In Paperbacks From Hell, Hendryx amusingly illustrates how Jaws gave birth to books about killer dogs, killer cats, killer rabbits, killer ants, killer slugs, killer maggots, killer scorpions, killer moths, killer worms, and just about every other kind of non-human creature on earth. Not every offspring of Jaws was pure dreck, either. Hendryx cites Stephen King’s 1981 killer-canine tale, Cujo, as one of the more respectable entries in the genre. Sutherland identifies John Godey’s 1978 thriller The Snake as not only a true offspring of Jaws, but also one of the best. He writes, “One work which does, perhaps, deserve some attention is John Godey’s The Snake. In this novel the Jaws-like plot device (an eleven-foot Mamba loose and killing in Central Park) is made secondary to grisly comedy about New York’s free-floating, always-on-the-boil hysteria. In consequence, The Snake seems to be as much a satire on Jaws mania as an imitation of the other novel…Godey’s novel focuses on the same trio of hunters as Jaws: an eco-OK herpetologist (who wants to save the reptile), a hard-nosed cop with a mid-life crisis and a vicious Jesus-freak sect who want to destroy the snake as the incarnation of evil.”

Book critics in 1974 described Jaws variously as a thriller, a tale of suspense, an action story, and “the best man-vs-fish story since 1851” (Moby Dick was frequently referenced in reviews of Jaws). John Sutherland noted that, “Essentially Jaws belongs not to the ‘literary’ tradition but to a bestselling entertainment fashion, or gimmick, of the early 1970s – the disaster story.” He was referring to novels such as Arthur Hailey’s Airport and Paul Gallico’s The Poseidon Adventure (as well as the hit films they spawned). But many, if not most, book critics of the era categorized Jaws as a horror novel. The reviewer for the Philadelphia Inquirer called the book a horror story and noted that, “Jaws proves once again that you don’t need demons or exorcists to create blanching, relentless terror.”

These days, horror novels and films tend to include some aspect of the supernatural. Without a supernatural element, they are usually just identified as gritty procedurals or supercharged thrillers. Back in the 1970s, however, pop cultural genres tended to be more loosely defined. Thus Jaws, which possessed no supernatural elements, was regarded by many as the best horror novel of 1974. Curiously, two months after the publication of Jaws, on April 5, 1974, Doubleday published another unknown author’s debut horror novel, this one with a strong supernatural twist. Doubleday had high hopes for this novel and put out an initial print run of 30,000 hardback copies. Alas, only about half of those were sold. The rest were remaindered or pulped. But two years later, when Brian De Palma’s film version of the novel was released, Stephen King’s Carrie became a massive paperback bestseller. If, on New Year’s Eve 1974, you had asked a publishing-industry insider to predict which debut novelist of 1974 would go on to become the most successful American horror novelist of all time, that insider would almost certainly have named Peter Benchley. Fifty years on, we now know that it was King who was destined to dominate American bestseller lists with horror and horror-adjacent books that would alter not only the pop-fiction landscape but the pop-cinema and television landscapes well into the twenty-first century. Meanwhile, Benchley and his books would largely be forgotten even before the end of the twentieth century.

The triumph of Stephen King over Peter Benchley would seem to be a very American story, a Horatio Alger-style tale of a working-class kid raised by a single mother and educated at a fairly ordinary state university who grows up to be a much more successful writer than the third-generation literary man and Harvard grad who had all of the advantages in life that the young King lacked. But the caricature of Peter Benchley as a nepo-baby has never been fair. His widow Wendy (to whom Jaws was dedicated) provided an introduction to the Folio Society’s recently published fiftieth anniversary edition of Jaws. In that intro she says of her late husband, “When he was fifteen and sixteen, he undertook a challenge set by his father, to commit to writing four hours a day during the summer. He could either sit alone in his small room each day staring at the typewriter keyboard or produce a thousand words. His father knew that being a full-time writer was a tough life, so he wanted to test Peter’s desire and determination for the craft. He expected that a rambunctious, athletic teenager would tire of the solitude and soon opt for more stimulating pursuits…Peter not only tolerated the discipline and isolation instilled in him by his father, he enjoyed them. At the age of seventeen, he began writing stories and sending them to magazines. He had all the qualities essential for a novelist: an intense curiosity, superb imagination, and the ability to always ask ‘what if’…He read about nautical history, underwater archeology, marine biology, the succession of English and Spanish monarchs, great 18th- and 19th-century writers, and, of course, sharks and other marine life. Years later, when the opportunity arose to talk to a publisher about a potential novel, he was ready not only with a couple of plot ideas but with the tools to create the story and the characters necessary for a gripping yarn.”

And even after Benchley’s fiction-writing career sputtered, he and Wendy remained highly active as environmentalists. For more than thirty years they worked with a variety of nonprofit organizations – the Environmental Defense Fund, WildAid, etc. – in an effort to protect and preserve the world’s oceans and their underwater inhabitants, especially sharks. That’s a legacy that even those who might never have been fond of Benchley’s fiction ought to commend.

Great essay, Kevin! I learned a great deal about Jaws... Peter Benchley sure had an interesting career.. and that film, while better known than the novel, sent many people back to the book... and, in my case, into reading Robert Benchley, too! Thanks for an excellent read.