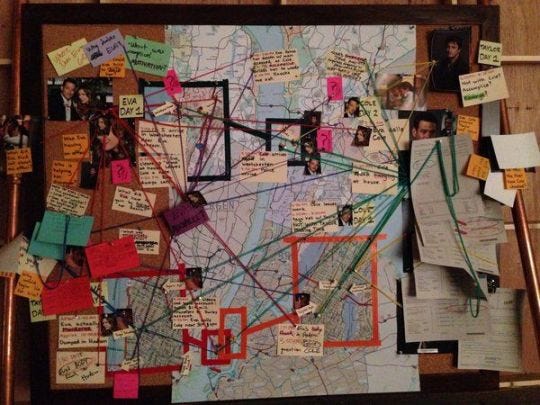

Back in the 1990s, when it first started appearing regularly on TV crime shows, the murder board seemed like a clever and useful device. With its requisite red strings and pushpins (or, if the cops were using a whiteboard instead of a corkboard, taped-up photos and felt-tip marker lines) the murder board served as a compact visual encapsulation of the state of a murder investigation. The murder board is supposed to be a tool used by the police but, in fact, was created by TV showrunners mainly to remind easily distracted or confused viewers who this episode’s victims were, who the suspects are, what the timeline of the case looks like, and so forth. I have no idea if real police detectives ever use murder boards. If they do, the murder boards they use probably look nothing like the ones on TV, which are fairly basic and contain info that any actual detective on the case probably wouldn’t need to be reminded of. Police files strike me as a much more efficient way of cataloging all the known facts about a criminal case. Alas, a police file is nowhere near as photogenic as a murder board.

By the turn of the twenty-first century, the murder board was ubiquitous on TV crime shows and had become nothing more than a lazy cliché. By now it has been parodied a million times. On the current NBC TV show Laid, the character played by Zosia Mamet creates a murder board to keep track of the sex life of her best friend, Ruby (played by Stephanie Hsu). At the end of the 2018 film Game Night, a murder board is used to illustrate the great lengths that a character played by Jesse Plemons has gone to in order to try to get into the good graces of his next-door neighbors (Jason Bateman and Rachel McAdams). Used in a comic setting on shows like Brooklyn 99 or Based on a True Story, the murder board still makes a bit of sense. Those shows exist in order to poke fun of crime drama clichés and, at this point, nothing is more cliched than the murder board. But it seems unlikely that any actual cops would use the kind of murder boards that show up on TV shows such as Castle or The Mentalist or Elsbeth or any number of other TV crime dramas. For one thing, these murder boards tend to sit out in plain sight in a high traffic area of the police station. While Castle and his cronies are studying their murder board, other cops are walking back and forth through the room, sometimes leading arrested perpetrators right past it. No effort is made to keep the sensitive info on these boards secret. When Castle and company leave the station, the murder board is left on display for all to see. A visiting crime reporter could easily catch sight of the board and take a photo of it with his cell phone. In the pilot episode of the ABC TV crime series High Potential, a janitor working in an empty police station late at night sees a murder board that has been left in plain sight and, after a bit of studying, solves the crime it depicts. A clever defense attorney might be able to argue that, by failing to keep information about the crime secure, the police have tainted the potential jury pool for the defendant’s trial. After all, if perps and janitors are allowed to see what’s on the murder board, who knows how many other members of the community may have seen the information?

It is notable that murder boards rarely make an appearance in a serious crime novel. This is because such boards would serve no purpose. Unless the murder board were depicted in a photo illustration, the info on it would simply have to be described to the novel’s readers in the same way that the contents of a police file would have to be described – in writing. Most of the handbooks I have read on how to write crime/mystery novels contain some variation on this piece of advice: To keep your reader from becoming confused by a complex mystery plot, you need to have your detective stop every hundred pages or so and recap his progress on the case to his client or his police chief or to a reporter or some other appropriate character. In this way he can also help remind the reader of all that he has learned over the course of his investigation. I have heard these recaps described by one author as being sort of like the landings of a staircase in a high-rise building. If you are going to climb the stairs from the ground floor to the twentieth floor of a building, you are probably going to want to stop and rest on a landing after every three or four flights of stairs. On conventional TV crime dramas, murder boards have become the equivalent of stairway landings. Every twenty minutes or so, the characters go to the murder board and cross off suspects who have been cleared by the ongoing investigation. This helps the viewer keep track of the story’s progress, but it has become such a hoary cliché that it also reminds the viewer of just how generic this particular crime show is.

You can watch any number of classic crime shows of yore — Columbo, The Rockford Files, The Streets of San Francisco, Starsky & Hutch — and never catch sight of a murder board. The time that contemporary TV detectives waste on murder boards would be much better spent out in the field, pounding the pavement, revisiting the scene of the crime, and interviewing witnesses — activities that help to lend the story a sense of place and help develop the characters’ personalities. A murder board is simply a flat, two-dimensional device with no obvious purpose other than to remind the viewer of what the detective has learned so far.

I read recently that many of the crime series that are made for Netflix and other streaming services are specifically targeted at distracted viewers — people who are texting friends on their smart phone or preparing a work presentation on their laptop computers. The phenomenon is known as “second screen programing.” In 2023, actress/writer/director Justine Bateman told an interviewer: “I’ve heard of showrunners who were given notes from the streamers saying ‘This isn’t second screen enough.’ Meaning that the viewer’s primary screen is the phone or the laptop and they don’t want anything on your show to distract the viewer from their primary screen, becuase if they get distracted they might look up, get confused, and go turn it off.” On January 2, PC Magazine writer Emily Dreibelbis Forlini published an article about this called “Netflix is Telling Writers To Dumb Down Shows Since Viewers Are On Their Phones.”

Apparently, most Netflix viewers want crime shows that are easy to follow, have obvious good guys and bad guys, and dialogue that spells out exactly what everyone is thinking. I’ve read that the dialogue on Netflix dramas is often repetitive — the same information will be repeated from scene to scene — because Netflix knows how distracted its viewers are and is catering to them. Apparently they have an entire formula designed for producing content that people can consume without having to pay too much attention to it. Netflix isn’t alone in this. I’ve noticed a lot of repetitive dialogue on other streaming platforms as well. In a TV culture like that, murder boards are likely to continue being a staple of crime dramas.

I’ve written elsewhere about another stupid cliche of the contemporary crime drama: the police interrogation room where, frequently, sophisticated and powerful people willingly sit down across from a police detective and answer question without an attorney present. In real life, this would almost never happen. In real life, cops have to be smart and persistent to solve crimes. On TV, all they have to do is bring suspects down to the station and then get them to talk. It’s not very entertaining but, if you are playing Angry Birds on your cell phone, you probably aren’t too bothered by it.

The murder board seemed clever and original when it first began appearing on TV shows several decades ago. Nowadays it is tired and trite. It is time for TV writers to kill off the murder board and come up with something more original to replace it with. Alas, if Netflix is right about its audience, most viewers will likely be too stupid or distracted to even notice the improvement. Some, in fact, might even complain about it.

Real cops often call out fictional crime programs for presenting obvious inaccuracies or illogical scenarios. I guess we can chalk up the murder board as one of those inaccuracies.

Not to toot my own horn, but I wrote an entire book about this trope ("Serial Pinboarding" 2020), coming to a similar conclusion as you :) But what I really wanted to point out was an article by Aki Peritz, who commented on an FBI recruiting campaign that used a murder wall in their advertising (and how ridiculous that is). Here is the link: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2022/02/fbi-crazy-stringboard-recruiting-campaign.html