Frank Sinatra's "Come Fly With Me" was the best-selling album in the United States for five weeks in 1958, but the irony of its popularity (or, perhaps, the source of its aspirational appeal) is that practically none of us could take up the offer to "glide, starry-eyed" on an aircraft with anybody in those days. More than 80 percent of the country had never once been on an airplane.

“How Airline Prices Fell,” by Derek Thompson The Atlantic, Feb. 28, 2013

Technically speaking, my first flight occurred in the spring of 1958, when Frank Sinatra’s Come Fly With me was the top-selling album in the U.S. and my father and my mother (pregnant with me at the time) flew back to Oregon from England, where they had lived during most of his four-year Air Force stint. I was conceived in Teddington, a suburb of London. My older sister (alive and well today) was born there, as was my older brother (who spent all three months of his life there, after which he was flown to Oregon, his only plane trip, to be buried in the same cemetery where his parents now reside). It was an era when airplane travel still had an aura of romance about it, which made it a frequent source material for pop cultural properties, and not just Frank Sinatra songs. The hugely successful 1960 stage play Boeing Boeing, written by Marc Camoletti, tells of a Parisian bachelor who is simultaneously dating three airline stewardesses. At one point it was listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the most performed French play in the world. In 1965 Paramount Pictures released a film version starring Tony Curtis and Jerry Lewis (Quentin Tarantino is reportedly a fan). The 1963 film Come Fly With Me was based, not upon Sinatra’s album, but upon Bernard Glemser’s 1960 novel, Girl on a Wing, described by its paperback publisher as “The no-holds-barred novel of the stewardesses who swing in the sky – and on the ground!” The 1969 film The Stewardesses remains the most profitable 3D film ever made (though far from the highest grossing). Coffee, Tea or Me?, a 1967 novel credited to two airline stewardesses, Trudy Baker and Rachel Jones (but actually written by American Airlines p.r. man Donald Bain), went through numerous printings in the late 1960s and early 1970s. And in 1968, ten years after Frank Sinatra released Come Fly With Me, the Beatles released their so-called White Album (widely regarded as the best rock album of all time), whose first track begins with a reference to the British Overseas Airways Corporation and the sound of a Vickers Viscount turboprop jet landing on a runway, a sound that recurs throughout the composition and introduces the next one. Airplane travel was one of the few aspects of the Sinatra era that retained its hipness into the era of The Beatles. Other musical odes to air travel included Peter Paul and Mary’s Leaving On a Jet Plane (written by John Denver), Marc Lindsey’s Silver Bird, the Steve Miller Band’s Big Old Jet Airliner, Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Travelin’ Band (“737 comin’ out of the sky…”), Gordon Lightfoot’s Early Morning Rain (“Out on runway number nine, a big 707 set to go…”), Elton John’s Daniel (“Daniel is traveling tonight on a plane…”), the Jefferson Airplane’s Blues From an Airplane, Crosby Stills and Nash’s Just a Song Before I Go, Susan Raye’s L.A. International Airport – the list goes on and on.

In those days, novels about aviation and the people employed in it – test pilots, mail pilots, commercial pilots, private pilots, barnstorming pilots, aeronautic engineers, stewardesses, airline founders, etc. – constituted a popular genre of fiction, a genre born in the early twentieth century and still alive today, but which probably peaked between 1950 and 1970. During that era books such as Ernest K. Gann’s The High and the Mighty (1953), which spent more than a year on the New York Times’ bestseller list, and Arthur Hailey’s Airport, which was the bestselling novel of 1968, seemed to be everywhere.

I took my first airplane trip as a non-fetus on the day I turned 13. I remember this because, for many Americans of my generation, your first airplane trip was a rite of passage, like your first sexual experience, something you never forgot. Back in those days, my family drove up from Portland to Lynnwood, Washington, every summer to visit our cousins who lived in that suburb of Seattle, which was home to hundreds of Boeing workers. My cousin Sam Marthaller, born the same year as me, became a Boeing Defense employee in the 1980s and spent much of his life working there (he died in 2017). In the summer of my thirteenth year, knowing what an airplane nut I was, my parents decided to buy me a one-way ticket to Seattle for my birthday. Naturally, they couldn’t afford to fly our whole family to Seattle (see the above-referenced Derek Thompson article for an excellent explanation of why air travel in America was so expensive until the late 1970s). And so, on Monday afternoon, August 16, 1971, my parents drove me to PDX and put me aboard a Northwest Orient Airlines flight to Seattle. I remember being amazed when my father told me that my aunt and uncle, who would be picking me up at the Seattle airport, would have to leave their home in Lynnwood before my flight departed Portland, in order to get to the arrival gate in time. My family was scheduled to drive up to Seattle the following day.

Back then an unaccompanied minor aboard an airplane got a lot of attention from the airlines. I was given a pair of tin pilot’s wings, several Northwest Orient stickers and decals, a few postcards featuring photographs of airplanes, and even some swizzle sticks with the company’s logo on it. I cherished all of this stuff and saved it for years in the bedroom of the house I grew up in. It probably contributed to my interest in airline fiction. I read a lot of it in the 1970s.

By the dawn of the 1970s, almost all bestsellers about commercial airplanes were thrillers about terrorists, hijackers, or doomed flights that crash landed in the Andes. But it wasn’t always thus. William Faulkner’s 1935 novel, Pylon, explores the life of barnstorming pilots in the early twentieth century. It appeared in the same year as Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s North to the Orient, an account of an aerial expedition she and her husband, Charles Lindbergh, took across the Arctic Circle. The book earned Lindbergh the first ever National Book Award for nonfiction. She followed it up in 1938 with Listen! The Wind, another National Book Award winner, which chronicled the couple’s aeronautic excursions in Africa and South America. Her 1944 novel, The Steep Ascent, inspired a reviewer for Kirkus Reviews to write: “The literature of flight has no more gifted contributor than Anne Morrow Lindbergh.” But other critics compared her to French aviator/writer Antoine de Saint-Exupery and found her wanting. Some of this may have been due to sentimentality on the part of the reviewers, for Saint-Exupery disappeared – and was presumed (correctly, as it turned out) to have died – shortly after The Steep Ascent was published and while it was still being assessed by critics. In any case, none of these books was about terrorism, hijacking, or doomed commercial flights. Passenger air travel was in its infancy back in the 1930s, and many of the books about flying focused on small aircraft containing just a pilot and perhaps a co-pilot, usually an adventurer or a mail deliverer.

To be sure, mystery writers seized upon the possibilities of felonies in the fuselage almost from the moment the Wright Brothers successfully executed the first flight of a heavier-than-air aircraft at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on December 17, 1903. Agatha Christie’s Death in the Clouds, published in the same year as Pylon and North to the Orient, is a mystery in which Hercule Poirot tries to figure out who murdered a French moneylender aboard a commercial flight from Paris to London. Isaac Anderson, reviewing the book in the New York Times on March 24, 1935, noted that, “[M]urder in an airplane is by way of becoming almost as common as murder behind the locked doors of a library…” Nonetheless, back in the early twentieth century, books exploring the felonious possibilities of air travel didn’t dominate the literature of flight the way they do now.

In 1974, Roberta J. Forsberg published a book that explored the works of two giants of airplane fiction. It was called Antoine Saint-Exupery and David Beaty: Poets of a New Dimension. The subtitle says it all. Much of the early literature of the airplane was closer to poetry than to pop fiction. In her introduction, Forsberg writes:

“The efforts of the nuts-and-bolts expert, the engineer first coming into his own in the nineteenth century, finally put man in the air. He made possible the experience of a new dimension by building an oily, smelly, noisy caricature of a bird, a long way from man gloriously aloft, as Botticelli and Tintoretto saw him. Many acknowledge the great aesthetic difference between the first awkward aeroplane and today’s transport. Some would even agree with James Morris in his [book] Venice when he calls the gondola and the jet aircraft the two most beautiful transportation artifacts ever created. But others, like Professor Tolkien, see no value in early or late machines. To them the aircraft is beautiful when distance makes it unrecognizable for what it is, when one is aware only of its birdlike flight against the sky.

“St. Exupery and Beaty reach the same end as Tolkien, a spiritualized, or even mystical view of the universe by the very means which Tolkien denounces. And, strangely enough, they appreciate the means as well as the achievement. They, like the mystics, rejoice in the material world as the first step on the way. They do not regret or even feel hampered by the instrument for, strangely enough, the spirit in them is also in it.”

St. Exupery is best known these days as the author of The Little Prince, a beloved children’s story. During his lifetime (1900-1944) however, he was known primarily for his books on aviation, such as the novels Southern Mail and Night Flight, and the memoir Flight to Arras, all of which are still widely read. Beaty’s fame has never equaled the Frenchman’s, but in the mid-twentieth century novels such as The Take Off, The Heart of the Storm, Call Me Captain, and The Proving Flight (many of them published under pseudonyms) drew wide praise for their authenticity and sharp prose. Saint-Exupery and Beaty both had plenty of flying experience. Both men served as wartime pilots in the military and as peacetime pilots in private industry. During World War II Beaty once returned from an attack on a German U-boat with more than 600 bullet holes in his airplane. After the war, he flew commercial airplanes for the very same BOAC that Paul McCartney sings about on the White Album. Many of his books celebrate not just airplane flight but the entire airline industry. The Heart of the Storm (U.S. title: The Four Winds) is described by its publisher as a “beautifully written novel [that] combines an unforgettable love story with the dramatic operations of a great overseas airline.” His novel Wings of the Morning (co-written with his wife Betty Beaty) is another pop fiction about romance and the rise of the aviation industry. When an airplane finds itself in trouble in a Beaty novel it is usually because of a powerful storm or a mechanical failure rather than criminal activity.

One of the first prominent novels to incorporate an airplane hijacking into its plot was James Hilton’s Lost Horizon, published in 1933. But the word “hijack” appears nowhere in Hilton’s book. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary the term first appeared in print in 1923. At that time it was used exclusively to describe the act of stopping a vehicle (usually a truck) on the highway and stealing it from its rightful owner (this happened fairly regularly in the U.S. during Prohibition, when trucks carrying substances that could be used to make alcohol were often stopped and pirated by criminal gangs). The term is believed to have derived from the phrase “Hold ‘em up high, jack!” supposedly uttered by the criminals who perpetrated the crime. In any case, the word hijacking wasn’t widely used to describe acts of air piracy until the 1960s. Throughout Lost Horizon, the characters refer to their own hijacking as a kidnapping, but the word sounds awkward in that context. For instance, consider this line of dialog from the novel:

“It’s curious when you come to think about it, that out of four people picked up by chance and kidnapped a thousand miles, three should be able to find some consolation in the business.”

Since none of the characters are held for ransom or prevented from leaving Shangri-La (the place they are eventually hijacked to), kidnapping doesn’t seem the right word in this scenario. And “kidnapped a thousand miles” makes the usage even more ungainly. Nonetheless, that word was about all that was available to Hilton at the time (the portmanteau “skyjack” didn’t come on the scene until decades later). What’s more, the plane hijacking in Lost Horizon is less in the nature of a crime and more in the nature of a convenient plot device for getting Hilton’s characters into a mythic paradise on earth. If he were writing the book today, his characters would probably be transported to paradise via some form of virtual reality (as in the Amazon Prime TV series Upload, or various episodes of Black Mirror) or a wormhole (as in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, Interstellar, and many others) or some other fantasy portal. But back in 1933, airplane travel was still novel enough to be used as the vessel of transportation into a fantasy realm. Shangri-La and the interior of an airplane were almost equally mysterious to your average American reader back then. So, although the book includes a crime, it is still part of the airplane-flight-as-spiritual-experience genre of pop fiction. As such, it was a forerunner of Fantasy Island, a popular TV series that ran from 1977 until 1984 and which always began with a planeload of adventurers arriving at a destination where all their dreams might be made to come true.

In the middle of the twentieth century, several pilots-turned-novelists rose to prominence primarily on the strength of their airplane fictions. They were as commonplace as lawyers who write legal thrillers are these days. Among the most famous of these was Nevil Shute (birth name: Nevil Norway), who was not just an airplane pilot but also an aeronautical engineer. Shute’s novels tended to emphasize the technical details of airplane flight over external dangers such as hijackers or daunting mountain ranges. The title character of his first novel, Stephen Morris, “studies aeronautical engineering and publishes a paper on fuselages,” according to a description of the book at Wikipedia. Not exactly the stuff of contemporary thrillers. The book’s sequel, Pilotage, focuses on the efforts of two men to launch a transatlantic cargo plane service. No Highway, Shute’s 1948 aviation novel, deals with…metal fatigue. Believe it or not, it became a nail-biting film experience when it was brought to the big screen in 1951 as No Highway in the Sky, directed by Henry Koster and starring James Stewart and Marlene Dietrich. Many of Shute’s other novels – Marazan, Landfall, Round the Bend, In the Wet, The Rainbow and the Rose, Pastoral, An Old Captivity, etc. – deal, directly or indirectly, with airplane flight. Slide Rule, his autobiography, focuses mainly on his love of airplanes.

Probably the most successful American pilot-turned-aviation-novelist was Ernest K. Gann. During the Second World War, Gann was one of the pilots whose job it was to fly warplanes “over the hump” from India into China, where they would be used to fight the Japanese. The “hump” was Air Force jargon for the Himalayas, the most difficult mountain chain in the world to fly over. Gann called the conditions of those flights “simply and truthfully the worst weather in the world.” Among his fellow “hump” aviators was American novelist John Ball (In the Heat of the Night). Gann’s first novel, Island in the Sky (1944), about a military airplane that ends up going wildly off course before crashing in a snow-covered frontier, was inspired by his exploits flying the hump, but as it was published while the war was still ongoing, he had to relocate the activity to Canada, to protect the secrecy of the hump project. His next novel, Blaze of Noon (1946), tells of the aviators who pioneered the delivery of airmail in the United States back in the 1920s. Other aviation novels by Gann include In the Company of Eagles (1966, about the fighter pilots of World War One), Band of Brothers (1973, about the crash of a commercial jet in Taiwan), and The Aviator (published in 1981, and with a plot at times so similar to the plot of the Tom Hanks film Cast Away that I’m surprised Gann wasn’t given some sort of story credit).

By the 1960s, novels about stewardesses were fairly common, but I’m not aware of any that were written by actual stewardesses. This is understandable. Airlines were brutal on stewardesses back then. Among other things, the stewardess wasn’t allowed to marry, wasn’t allowed to get pregnant, wasn’t allowed to turn 30, and wasn’t allowed to gain weight (legally, of course, she could do all those things, but she’d lose her job if she did). According to Come Fly With Us! A Global History of the Airline Hostess, written by Johanna Omelia and Michael Waldock, the average stewardess’s career lasted about two years. In fact, airlines enticed attractive women to the job by promising them that they’d be married before they reached their second anniversary with the company. An American Airlines pamphlet cited by Omelia and Waldock informed prospective stews that “within two years most American stewardesses leave their jobs to get married.” The pamphlet assures the reader that, “This isn’t surprising. A girl who can smile for 5 hours is hard to find. Not to mention a wife who can remember what 124 people want for dinner.” Ha ha. Thomas Hobbes might have been describing the life of a 1960s-era stewardess when he said that life is “nasty, brutish, and short.” Numerous studies have shown that air hostesses, even today, are some of the most sexually harassed employees in the North American workforce. A study published in August of 2020 in the International Journal of Aerospace Psychology found that 26 percent of flight attendants in the U.S. and Canada reported being sexually harassed on the job. The numbers were probably much higher back in the 1960s, when much of what we now regard as sexual harassment was likely deemed merely flirtatious behavior. Few actual stewardesses of the era spent enough time in the profession to write about it as knowledgably as Shute, Gann, and other pilots wrote about flying planes. Which probably explains why most of the spicy stewardess novels of the 1960s were written by men with no actual experience as flight attendants. Nonetheless, one near-masterpiece did eventually rise above all the dreck, but we’ll get to that in due time.

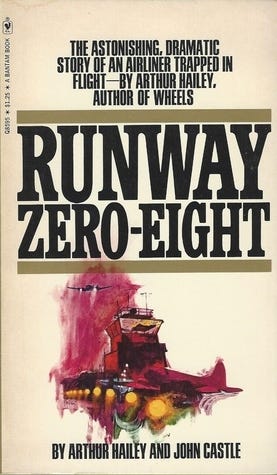

Back in the 1940s and the early 1950s nearly every new publishing season brought another round of airplane novels that were actually about airplanes. By the late 1950s, however, air travel was beginning to seem less like a new frontier and more like a playground for the rich and fashionable – the “jet set,” as they were called, a term that replaced the outdated “café society.” As a result, airplane fiction began to change its focus from the mechanics of flying to the lives and loves of the wealthy people who traveled for pleasure, globe-hopping from one exciting destination to another. Naturally, virile airline pilots and sexy young stewardesses figured prominently in these tales. Even when these tales were thrillers, however, they tended to avoid criminality. Runway Zero-Eight, Arthur Hailey’s first novel (co-written with Ronald Payne and John Garrod, who used the pseudonym John Castle, and technically a novelization of Flight Into Danger, a phenomenally successful 1956 Canadian TV film Hailey had written), tells the story of a chartered jet carrying a bunch of Canadian sports fans from Toronto to Vancouver for a big game (I don’t think the sport is ever revealed). Shortly after the stewardess serves dinner, the passengers who opted for the salmon over the pork begin suffering agonizing bouts of food poisoning (foul play is never even suggested). Unfortunately, both the pilot and the co-pilot opted for the salmon and become debilitated as a result. Before the magnitude of the looming disaster has been disclosed to the passengers, a doctor aboard the plane (which is now flying on auto-pilot) makes a discrete effort to find out if any of the passengers have experience piloting a plane. Eventually, he finds someone who flew fighter jets in the war (which would be highly unlikely nowadays but not in the mid 1950s, when World War II veterans were commonplace everywhere). Alas, the fighter pilot flew single engine planes that were roughly as complex as a 1956 Volkswagen Beetle, and he has no experience whatsoever in the cockpit of a jumbo jet. Fortunately, with the aid of a scrappy stewardess who has a decent working knowledge of the jet’s instrument panel, the ex-fighter pilot lands the plane safely in Vancouver. Published in 1959, the book was fairly typical of the airplane fiction of its era – i.e., air flight is portrayed as a somewhat upscale venture, crime plays no role, and the heroes are a middle-aged ex-military pilot and a sexy young stewardess. By 1968, when he published the phenomenally successful Airport, Hailey was strewing his airplane fiction with insurance fraudsters, suitcase bombers, and stowaways. And that became the template for much of the airplane fiction that would follow (it also became the template for a franchise of increasingly ridiculous films, all of which would be spoofed in the hugely successful 1980 comedy Airplane!, which grossed $171 million on a budget of $3.5 million). So what turned the airplane novel into just another genre of crime novel? I blame D.B. Cooper and his ilk.

Exactly one hundred days after I took my first non-fetal airplane ride, the same Northwest Orient Airlines flight departed from PDX and headed to Seattle, only to be hijacked by a man the media (mis)identified as “D.B. Cooper.” Shortly after takeoff, he handed 23-year-old stewardess Florence Schaffner (quite possibly the same stewardess who pinned my pilots wings on me back in August of that year) a note informing her that he had a bomb and that he would blow up the airplane unless he was given $200,000 cash and four parachutes when the plane landed in Seattle. It took a while for the airline and the FBI to meet these demands, so the airplane was forced to fly in a holding pattern over Puget Sound for two hours. Eventually the plane landed in Seattle, the passengers and all but one of the stewardesses (22-year-old Tina Mucklow) were allowed to leave the plane. “Cooper” was given a canvas knapsack containing 10,000 $20 bills. He was also given four civilian parachutes (he rejected the military chutes he was originally offered). At about 7:40 p.m., after discussing his flight plans with the cockpit crew (captain, co-pilot, and flight engineer) the hijacker forced the plane back into the air, and ordered it flown to Reno, Nevada. He sent Mucklow up to the cockpit and ordered her to lock it. Now he was alone in the plane’s cabin. At about 8:00 p.m., the airstairs at the rear of the plane opened and shortly thereafter the hijacker parachuted into the Washougal Valley, in the southwest part of the state of Washington. To this day, his fate, and even his identity, remain a mystery (although theories abound).

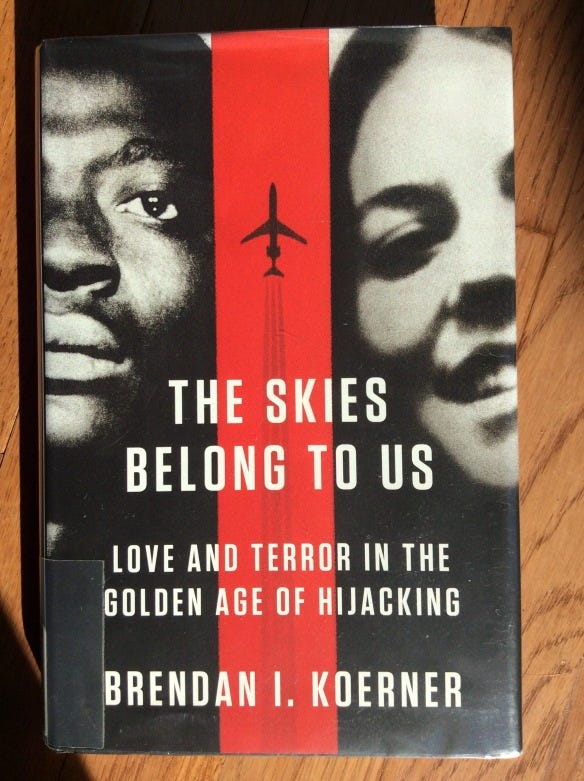

D.B. Cooper was hardly the first person to hijack a jetliner. In fact, he was a bit of a Johnny-come-lately to the crime. According to The Skies Belong To Us: Love and Terror in the Golden Age of Hijacking, Brendan I. Koerner’s excellent study of the subject, “Prior to the spring of 1961, there had never been a hijacking in American airspace.” That ended on May 1, 1961, when a Miami electrician hijacked a commuter plane bound for Key West and forced it to fly to Cuba. The hijacker was arrested in Cuba and the plane was allowed to depart shortly thereafter. America’s first hijacking, according to Koerner, delayed the plane’s arrival in Key West by only three hours. It was a minor inconvenience and no one at the time saw it as the harbinger of a horrible new trend. But less than three months later, an Eastern airlines flight was hijacked to Cuba. Eight days later, a passenger attempted to hijack a flight from Chico, California to Smackover, Arkansas, but was foiled by fellow passengers who attacked and subdued him. Two days later a Continental Airlines flight out of Phoenix was hijacked. Up until 1961, hijacking wasn’t even a recognized federal crime in the U.S. Those who committed it could only be charged with kidnapping and other related offenses. In September of 1961, to put an end to the mini-spree of hijackings, Congress quickly passed and President Kennedy signing into law a bill making air piracy a capital offense. And that seemed to do the trick. No additional hijackings occurred in American airspace for the rest of the year. Neither were there any hijackings in 1962, 1963, or 1964.

Alas, the lull ended in 1965. Convinced that Fidel Castro was creating a socialist paradise in Cuba, many sadly deluded Americans began hijacking planes to Havana in the mid-1960s, when the hippie-era search for peace and freedom was beginning to flower. These utopia-seekers had no other choice, because the American government’s embargo made it impossible to travel to Cuba legally. One Cuban-American who knew for certain that Cuba was no paradise, nonetheless hijacked a plane to Havana because, according to Koerner, “he could no longer bear to live without his mother’s delicately seasoned frijoles.” As so often happens with those who seek paradise on earth, these hijackers mostly found only greater misery. Fidel Castro despised the hijackers, and was convinced they were CIA spies. After deplaning in Havana, the hijackers usually spent weeks being interrogated and tortured by Cuba’s secret police. If the hijacker could convince his inquisitors that he was no spy, he was sent to live in a dormitory where each American hijacker was allotted 16 square feet of living space. At times, as many as 60 Americans occupied this dormitory. Less fortunate hijackers were sent to work in sugarcane fields under miserable conditions. If they objected to their treatment or tried to escape, they would be executed, or hacked at with machetes, or dragged through a cane field until the flesh was stripped from their bodies. The U.S. government tried to warn potential hijackers of these dangers but, during the Vietnam War era, the U.S. government was deemed by many to be less credible than Fidel Castro’s.

By the late 1960s, so many flights were being hijacked to Cuba that the Federal Aviation Administration considered building an exact duplicate of Havana’s Jose Marti International Airport on the coast of Florida. The pilots of hijacked airplanes would then land their jets at this fake airport and American air marshals dressed as Cuban authorities would come out to greet the hijackers with open arms, handcuffing and arresting them as soon as it was safe to do so. The plan never got off the drawing board. In February of 1969, Alan Funt, the host of a popular TV show called Candid Camera (a precursor of Punked), was flying aboard an Eastern Airlines flight bound from Newark, New Jersey to Miami, Florida, when it was hijacked by two men who demanded to be taken to Cuba. The other passengers had seen Funt boarding the plane and assumed that the hijacking was a prank that was being filmed for TV. Funt did his best to convince his fellow passengers that the hijacking was not a joke, but they mostly refused to believe him. At one point they gave the hijackers a standing ovation. Only when the plane landed in Havana and they were held in captivity by the Cuban authorities did most of Funt’s fellow travelers realize that they were not participants in an elaborate practical joke.

American government officials were eager to put an end to this rash of hijackings but they received fierce opposition from an unexpected source – the airlines themselves. Air travel back then was still primarily a rich man’s mode of transportation. And the airlines feared that if they inconvenienced their well-off customers with long and humiliating luggage-searches, X-rays, and pat-downs, their profits might begin to suffer. Generally speaking, it was less expensive for the airlines to put up with the occasional detour to Cuba than it would have been to institute stricter security protocols. Castro charged the airlines $7,500 before he’d allow a hijacked airliner to return to the U.S., but the airlines considered that fee a bargain compared to the cost of installing X-Ray machines at every terminal gate in the U.S. In fact, the official policy of most major airlines was to make no effort to thwart a hijacking attempt in progress. According to Koerner, “every airline adopted policies that called for absolute compliance with all hijacker demands, no matter how peculiar or extravagant…To facilitate impromptu journeys to Cuba, all cockpits were equipped with charts of the Caribbean Sea, regardless of a flight’s intended destination. Pilots were briefed on landing procedures for Jose Marti International Airport and issued phrase cards to help them communicate with Spanish-speaking hijackers…Switzerland’s embassy in Havana, which handled America’s diplomatic interests in Cuba, created a form letter that airlines could use to request the expedited return of stolen planes.”

Long before D.B. Cooper became a household name, plenty of other hijackers enjoyed their own dose of fame. Leila Khaled, an attractive member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (which is now categorized as a terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department) became something of a media darling after she participated in the attempted hijacking of a TWA flight to Damascus in 1969. Many media outlets seemed more interested in her good looks and her fashion sense than in her criminal activity. Her face became so well known that she had to undergo multiple plastic surgeries in order to continue working as a hijacker. Now 77 years old, she lives with her family in Jordan, but has occasionally gone on speaking engagements in the U.K. and Sweden.

In May of 1969, U.S. Lance Corporal Raffaele Minichiello, who earned a Purple Heart for his service in Vietnam, hijacked a plane in Los Angeles and demanded to be taken to Italy, the country of his birth (he was angry because he believed the Marines had cheated him out of money he was owed). When he finally got to Italy (it took several changes of airplane to get him there) he was greeted as a national hero. The Italians, like many others in Western Europe, despised American policy in Vietnam, and admired Minichiello’s willingness to speak out against the U.S. military, even if his beef was just a personal one. Film producer Carlo Ponti wanted to make a film of Minichiello’s life. Teenage girls worshipped him as if he were a rock star. The Italian courts gave him a light sentence for his crime (eighteen months in prison) and refused to extradite him to the U.S. When he got out of jail he was offered a role in a spaghetti Western.

As you can see, Cooper wasn’t exactly a pioneer in the annals of air piracy. Not only was he not the world’s first hijacker, he wasn’t even the first to attempt a parajacking. Eleven days before Thanksgiving 1971, 26-year-old Paul Joseph Cini boarded an Air Canada flight from Calgary to Toronto carrying a parachute that was concealed in tightly wrapped paper and tied up with twine. No one paid much attention to the parcel because they were focusing instead on the shotgun and the dynamite he was carrying. He stuck a stick of dynamite into the mouth of a stewardess and demanded to see the captain. Once inside the cockpit, he identified himself (falsely) as a member of the Irish Republican Army. He demanded $1.5 million and passage to Ireland. The captain landed the plain in Great Falls, Montana, where airline officials had scrounged together $50,000 in cash. Cini didn’t seem to notice that the ransom was $1.45 million short. He forced the plane back into the air. He had been planning this crime for a long time and had determined that the only way to successfully hijack a plane for money was to parachute out of it once the ransom had been delivered. Alas, Cini had tied up his package too tightly. He couldn’t undo the knots in the twine. He asked the captain for help. The captain handed him a fire axe and suggested he use it as a cutting tool. Cini, apparently an idiot, set down his shotgun and reached for the axe, whereupon the captain kicked the shotgun away and wrapped his arms around Cini’s neck. Another crew member grabbed the fire axe and slammed it into Cini’s skull. Thus ended the world’s first parajacking attempt. Had he not been a bit overzealous with the twine, Cini might have reaped the fame and glory that would soon be D.B. Cooper’s.

So why, when hijackings were so commonplace in the early 1970s, does D.B. Cooper remain not only the most famous skyjacker in history but pretty much the only famous skyjacker in history, the only one, anyway, whom most people can probably identify by name? The answer isn’t that complicated. When someone or something vanishes without a trace it defies the natural order of the world. We’re used to a certain predictable narrative surrounding people, places, and things. They arrive, they exist for a while, and then they die and are buried. The RMS Titanic held a larger place in the world’s collective consciousness before Robert Ballard and his crew located its watery grave in September of 1985. Before that, for 73 years, people couldn’t help but be obsessed with the idea that a ship that was nearly three football fields long and as tall as a 17-story building had simply vanished without a trace, despite the fact that hundreds of people witnessed its sinking and lived to tell about it. Plenty of famous aviators have died while pursuing their passion for flying – Wiley Post, Denys Finch Hatton, John F. Kennedy, Jr. – but none of these men retain the mythic status of Amelia Earhart who also appears to have died doing what she loved. We don’t really know what happened to Earhart because one day, like the Titanic, she simply vanished. And, unlike the Titanic, she and her airplane have thus far eluded all attempts to locate their remains. The same would appear to be true of D.B. Cooper. On Thanksgiving Day, 1971, he stepped out of the back end of a Boeing 727 in midflight and simply vanished. No one really knows what became of him, and that excites the human imagination. But, as Koerner points out in The Skies Belong to Us, Cooper’s fate is fairly easy to guess at:

Experienced skydivers scoffed at the notion that Cooper could have survived his jump. The man seemed to know virtually nothing about skydiving, as evidenced by the fact that he jumped without a reserve chute and didn’t ask for any protective gear. The plane was traveling at roughly 195 miles per hour when Cooper exited, a speed that even experienced parachutists consider unsafe; it is possible that Cooper was knocked unconscious immediately after jumping. No professional skydivers attempted to jump from a Boeing 727 until the 1992 World Freefall Convention in Quincy, Illinois. One participant, who jumped at an airspeed of “only” 155 miles per hour, was amazed by the violence of the experience. “The first thing you noticed after exit was the heat from the jet engines and the smell of jet fuel,” he said. “There was a dead void, then the blast from jet steam. It felt like I was being tackled from behind.” Even if [Cooper] did survive the initial plunge through subzero air temperatures and pounding hail, the terrain below was lethal – nothing but hundred-foot-tall fir trees and frigid lakes and rivers. Like so many skyjackers before him, Cooper was probably too psychologically askew to have thought his plan all the way through.

Nonetheless, by disappearing into the ether, Cooper became a folk hero of sorts and the media couldn’t let his story die. As Koerner notes, “By now well-versed in the contagious nature of skydiving, the airlines and the FBI both braced for the inevitable post-Cooper outbreak. But they were still woefully unprepared for the utter mayhem of 1972.”

The year 1972 was the annus horribilus of 20th century passenger aviation in America. Six American commercial planes were hijacked in January of that year alone. In one incident, Ex-Army paratrooper Richard LaPoint, clearly inspired by Cooper, collected two parachutes and a ransom of $50,000 in Reno, Nevada, and then forced the plane he had hijacked back into the air. He parachuted from the plane somewhere over a sparsely populated patch of Colorado. Alas, he made his jump wearing cowboy boots with nothing in the way of shock absorption in their soles. The landing damaged his feet so badly that he lay immobilized on the ground until the FBI, which had placed hidden tracking devices in the parachute, found him with ease and arrested him. When he was brought to court for a preliminary hearing, the judge told him that, as a military veteran, he was entitled to free medical treatment for his damaged feet. As Koerner tells it:

The Vietnam War veteran grumbled a reply that resonated with untold thousands of ex-soldiers struggling to cope with life after combat: “How ‘bout some mental assistance instead?”

Like Paul Joseph Cini, who set down his shotgun in the middle of a parajacking attempt, most of the hijackers of the Golden Age weren’t thinking too clearly. Many of them, like LaPoint, were American military veterans whose psyches had been damaged in the Vietnam War. Some were recent draftees hoping to evade service in Vietnam. Oftentimes these hijackers commandeered small commuter planes with a range of about 500 miles and then demanded to be taken to Europe or Africa or Vietnam. They might just as well have asked to be taken to Shangri-La. One of the January 1972 hijackings was carried out by a former mental patient. One was the work of an American military pilot who had carried out secret missions for the CIA in Laos and was wracked with guilt over it. Another was carried out by a father trying desperately to raise money for his son’s open-heart surgery (an FBI agent blew off the father’s head with a shotgun as he tried to flee with $200,000 cash). One hijacker told the captain he wanted the jumbo jet to land in Coos Bay, Oregon, a small town with no major airports nor even a runway large enough to accommodate a commercial jet. In April of 1972, a Mormon Sunday School teacher hijacked a United Airlines flight, collected a ransom of $500,000, and parachuted safely to the ground. Alas, he had worn no gloves and left his fingerprints all over the airplane, making it easy for the FBI to identify and catch him. In June of ’72 former Army paratrooper Robb Heady, holding a canvas bag containing $155,000, jumped from a hijacked plane somewhere near Washoe Lake in Nevada. The FBI, while cruising the area, found an empty car with a bumper sticker identifying the car’s owner as a member of The U.S. Parachute Association. They staked out the car and arrested Heady when he came limping up to it (he was injured upon landing and lost the bag with the money as soon as he leapt into the jet wash). A Navy vet named Martin McNally jumped out of a hijacked plane clutching a bag containing $502,000 in cash. Like Heady, he lost his grip on the money as soon as he left the pressurized cabin. When the FBI tracked him down at his home a few days later, he had $13 to his name. An AWOL soldier hijacked a passenger plane in the skies above Sacramento and forced it to fly to San Diego, where he demanded to be given $450,000, a parachute, and…written instructions on how to skydive. These people weren’t exactly criminal masterminds.

Cooper became a legend simply because his hijacking remains the only unsolved act of air piracy in aviation history. Koerner’s book focuses much of its attention on Cathy Kerkow (pictured above), who, along with her boyfriend Roger Holder, successfully managed to hijack a Western Airlines flight traveling from Los Angeles to Seattle. The couple negotiated a $500,000 ransom payment, and arranged to have themselves flown, in several stages, to Algeria. The money was seized by the Algerian government when the couple arrived at the Algiers airport. Algeria at that time was the home of many American fugitives from justice, most famously Eldridge Cleaver, a founding member of the Black Panthers. Holder (an African American) and Kerkow thought they would be treated by the Algerians as heroes in the fight against American imperialism. Mostly they were treated like unwanted guests. Even the Black Panthers, who had a large presence in Algiers at the time, wanted nothing to do with Holder and Kerkow once it was clear that the Algerian government would not allow them to keep the ransom money. Broke and miserable, they eventually made their way to Paris under false names. Holder, never very psychologically strong, soon grew homesick and unstable. When he was approached one night by Paris police officers who probably just wanted to warn him not to loiter, he gave them the entire story of his exploits as a hijacker. He even gave them the address where he and Kerkow were currently living. The police officers didn’t take him seriously and told him to go home. A few days later the Paris police reported the conversation to the American embassy. The Americans were outraged and demanded that Holder and Kerkow be arrested. The police raided the address Holder had given them, but he and Kerkow had already bolted from it. Eventually they were caught, but the French courts refused to extradite them to America. France has a long history of refusing to extradite suspects accused of politically motivated crimes. Instead, the French planned to try the hijackers in Paris, under French law. While their case dragged out in court, Holder and Kerkow were ordered to remain in Paris. This proved to be agony for Holder, who longed to return to America, but not for Kerkow. She ended the sexual relationship with Holder and began to blossom as a darling of the Parisian leftwing intellectual set. She wore the latest fashions and quickly became fluent in French. Jean Paul Sarte fell particularly hard for her and wrote a letter to the court urging her acquittal. She dated several wealthy Frenchmen in the film industry and became a good friend of Maria Schneider, Marlon Brando’s co-star in the X-rated 1972 film Last Tango in Paris, which made Schneider notorious worldwide just a few months after the Algiers hijacking had made Kerkow notorious worldwide. Holder wanted nothing more than to return to America, even if it meant serving some jail time. But Kerkow had become enamored of European life. She had no desire ever to return to America. In 1978, while the case against her was still slowly working its way through the French judicial system, she slipped out of France and into Switzerland. Her whereabouts have remained a mystery ever since. According to Koerner, “The likeliest scenario is that Kerkow returned to France after obtaining false documents in Switzerland, then melted into French society under an assumed name. Perhaps she married a wealthy boyfriend, who arranged for her to obtain French citizenship and relocate to a provincial town where she would attract little notice…After a few years of adjusting to her new milieu, Kerkow would have become indistinguishable from those around her.” Holder wasn’t quite as lucky. He was finally tried in Paris in 1980 and found guilty of hijacking and kidnapping. He was given a suspended sentence that required that he remain at large in France for five years. By now he was so sick of France that he probably felt as though he were serving hard time. He flew to America the day after his suspended sentence concluded, and was arrested by the FBI the moment he landed. He was 36 at the time. In March of 1988, after several more years of legal wrangling in America, he finally pled guilty to interfering with a flight crew, a much less serious offense than hijacking. After a brief stay in prison, he returned to California. On February 6, 2011, he dropped dead of a brain aneurysm in his San Diego home. He was 62, a chain smoker, and had suffered from mental and physical maladies for much of the previous three decades, many of them stemming from his service in Vietnam. Kerkow, a former high school track star (she was a teammate of the legendary Steve Prefontaine), was always much healthier than her former boyfriend. Odds are that she is still alive. If so, she turned 70 in October of 2021, and is still being sought by the FBI.

At the time of the hijacking, Kerkow was a young and extremely attractive hippie chick with an interesting back-story. The $500,000 ransom she and Holder extorted from Western Airlines was a record at the time. It’s difficult to explain why, in the media and the public eye, she never acquired the same glamour as Cooper, a bland-looking, middle-aged cipher who collected a ransom less than half of Kerkow and Holder’s and who almost certainly plummeted to his death after foolishly stepping out into the frozen void above the Washougal Valley. Everything we know for sure about Cooper occurred between 2:50 p.m. and 8:13 p.m. on November 24, 1971. Not only does he have no back-story, he has almost no story at all. Just as Fred Astaire got more praise than Ginger Rogers, who did everything he did but backwards and in high heels, Kerkow surpassed Cooper in every aspect of the art of hijacking but remains largely unknown to most Americans (and no doubt hopes to keep it that way). This is one female pioneer that even feminists have no desire to celebrate.

By the end of 1972, the airlines and the Nixon administration had had enough of hijacking. On December 5 the Federal Aviation Administration declared that all passengers in American airports must be scanned with a metal detector before boarding a flight. Furthermore all carry-on items had to be inspected before they could be brought on board. A short time later, the U.S. and Cuba agreed on a treaty that would return all future American hijackers to the U.S. from Cuba. The new rules proved amazingly effective in curtailing hijackings of American airplanes. Not a single plane was hijacked in American airspace in 1973. A single plane was hijacked, to Cuba, in 1974. But the plane quickly returned to the U.S. and the hijacker was prosecuted under American law. Soon the Golden Age of hijacking became just a memory. Alas, the damage to aviation fiction was already done.

Airplane fiction had begun turning mostly dark and felonious a few years before D.B. Cooper’s rise to fame. The first hijacking novel published during the Golden Age of Skyjacking was Desmond Bagley’s High Citadel, published in 1965. It’s the tale of a Communist agent who hijacks a passenger plane in a fictional South American country and forces it to crash land in the Andes. In 1964, when Bagley, a Brit, was writing the book, years had passed since the last hijacking in America. He may have felt that setting a hijacking tale in a sophisticated Western democracy would make it seem implausible. But, as we have seen, 1965 was the beginning of a Golden Age of such hijackings. Bagley had been ahead of the curve. Arthur Hailey’s Airport, the bestselling novel in America in 1968, was a hybrid of old-style aviation concerns – bad weather, a pregnant stewardess (a firing offense back in the day), a lost United Airlines food truck, a runway rendered unusable due to a stalled Mexican jet – and more contemporary ones – a bomb-carrying psychopath, for instance. But from about 1970 on, most novels dealing with commercial air travel were primarily thrillers. David Harper’s underrated 1970 thriller, Hijacked, tells of a commercial flight from New York to San Francisco that is hijacked by a person unknown (a stewardess finds a message written in orange lipstick in the bathroom: “I’ve hidden a bomb aboard this plane and can set it off anytime with a radio…”). The book (the source of a lackluster 1972 film starring Charleton Heston) combines the old-fashioned pleasures of a whodunit with the recently birthed genre of the hijacking thriller. Thomas Harris’s 1975 debut novel, Black Sunday, tells the story of Palestinian terrorists who plan to cause widespread death and destruction at the Super Bowl by blowing up a fictional version of the famous Goodyear blimp above the stadium. But the novel was clearly inspired by the Golden Age of hijacking. One of the main terrorists, Dahlia Iyad – a young and beautiful Lebanese terrorist known for her sense of style – seems to have been at least partially based on the aforementioned Leila Khaled. Iyad, like Khaled, specializes in airport-related terrorism. And the American pilot she recruits to execute her plan is, like so many of the hijackers of the Golden Age, a psychologically damaged Vietnam vet. Also released in 1975, Lucien Nahum’s Shadow 81, has all the elements of a Golden Age of Hijacking thriller: a disturbed Vietnam War vet with piloting experience, terrorism, the threatened hijacking of an American commercial jet, and a $20 million ransom demand. Reviewers tended to be more keen on this novel than Harris’s. Kirkus Reviews gushed, “A great plane robbery…improbable but you’ll forget all about that while you read it…A grandiose story, to be sure, but fine seat-of-the-pants entertainment with not a moment to lose.” Unlike Harris, who went on to write two of the best-known thrillers of the next two decades (Red Dragon and The Silence of the Lambs), Nahum never wrote another book, so his hijacking thriller has been unjustly forgotten (though apparently it remains perennially popular in Japan). Nelson DeMille’s 1978 novel, By the Rivers of Babylon, is about Palestinian terrorists who blow up one Concorde jet and force another to crash land in the desert. Thomas Block’s 1979 novel, Mayday, tells the story of some commercial airline passengers who must try to land the plane themselves after the captain and crew have been killed by an errant missile that struck the plane (curiously, Nelson DeMille collaborated with Block on an update of this thriller in 1998). Block produced several other aviation thrillers, including 1982’s Skyfall (in which a commercial jet is hijacked), and 1984’s Forced Landing, a smorgasbord for hijacking fans, which includes the hijackings of a submarine, a floating aircraft carrier museum, a Learjet, and a DC-9). The Fourth Angel, a thriller by Robin Hunter (a pseudonym for British historian Robin Neillands) tells of a passenger-plane hijacking and its violent aftermath. In Walter Wager’s 1987 thriller 58 Minutes, terrorists take over JFK airport in New York City and attempt to crash planes from the air-traffic control tower (if that sounds familiar, it’s probably because this book was the source of the film Die Hard 2, released in 1990).

Not all of the aviation novels that appeared in the wake of the skyjacking tsunami were crime novels. That’s the good news. The bad news is that many of them were written by Richard Bach, the bestselling aviator/novelist of the 1970s. His books sold zillions of copies but were mostly just turgid New Agey meditations on, well, Richard Bach. His “novel” (it can be read in half an hour and forgotten in less time than that) Jonathan Livingston Seagull was the bestselling work of fiction in America for both 1972 and 1973. It is a slight fable about a bird (obviously representing the author) who is more brilliant than all the others and knows more about flying than all the others and has made it his life’s mission to pass his wisdom on to the poor saps who lack his brilliance. The book seems clearly to have been inspired by Lost Horizon. The protagonist of James Hilton’s novel is guided through Shangri-La by a character named Chang. When J.L. Seagull’s brilliance allows him admission to a higher spiritual plane, he is guided through it by a character named Chiang. Both Hilton’s protagonist and J.L. Seagull decide not to remain in their spiritual utopia but rather to return to the ordinary world and try to do good there. Curiously, one of the greatest fliers J.L. Seagull meets in the higher plane is nicknamed Sully, which is also the nickname of probably the most famous airline pilot of the 21st century. The book is harmless drivel, but its mega-success seems to have convinced Bach that he was born to be a messiah. He followed it up with a “novel” called Illusions: The Adventures of a Reluctant Messiah. A better title might have been Zen and the Art of Airplane Maintenance. Once again, as in Lost Horizon, we have a westerner (in this case, Richard Bach himself) receiving life lessons from a character (in this case, a mysterious pilot named Donald Shimoda) who seems to represent the mysticism of the Orient. In this book, Bach not only claims to have learned how to walk on water, he goes Jesus one better by also learning how to swim through solid ground. On the first page of Illusions, Bach tells us, “I do not enjoy writing at all.” At the end of the book he tells his spiritual advisor, Shimoda, that he has promised himself “never to write another word again in my life.” If only. Each Richard Bach book is the story of how Richard Bach, thanks to lessons he learned while flying small airplanes, became much more spiritually and intellectually evolved than the rest of mankind (Jonathan Livingston Seagull tells this same story metaphorically). Bach and first wife, Bette Jeanne, had six children together. But after his first taste of success, Bach ditched his wife and kids (no doubt in a spiritually appropriate fashion), leaving them to fend for themselves. He didn’t just ask for a divorce; rather he pulled a disappearing act worthy of D.B. Cooper himself. If you don’t believe me, you can read Patterns: Tales of Flying and of Life, by Bette Jeanne, who is now known as Bette Bach Fineman. In it she tells of struggling to keep her brood fed and clothed after the great messiah ran out on them. Or you could read Above the Clouds, by Jonathan Bach (named after his father’s fictional seagull). In his brief prologue, he writes: “This book is about what happened after my father, author Richard Bach, left my family when I was two years old. This is what I did about the Unchangeable clouds that masked my sun for the next twenty years.” Chapter One begins: “In 1970, Daddy walked out the screen door of our house and drove away. Three years later, I started to learn why.”

Bach’s desertion devastated his family, but he himself seems to have walked away from the wreckage without a scratch. His 1984 book, The Bridge Across Forever, is about his search for a soul mate. As it turns out, his soul mate is gorgeous Hollywood actress Leslie Parrish, who has dozens of TV and movie credits on the Internet Movie Database, all of which predate her marriage to Bach (the wife of a messiah probably doesn’t have a lot of time for a career of her own). He followed up The Bridge Across Forever with a book/novel/whatever called One, in which he and Leslie go back in time (via an airplane piloted by Bach, natch) to communicate with their younger selves in an effort to help them avoid certain mistakes. Although only the name Richard Bach appears on the book’s cover and copyright page, he assures us in Chapter One: “We write together now, Leslie and I. We’ve become RiLeschardlie, no longer knowing where one of us ends and the other begins.” In 1999 RiLeschardlie divorced themselves and Richard, in that same year, married a much younger fan of his. That marriage ended in divorce in 2012. And you thought seagulls mated for life. Also in 2012, the great aviator clipped some power lines with the landing gear of a small plane he was piloting, crashed landed the plane upside down in an undeveloped grassland, and triggered a brush fire. So it seems that American pop fiction isn’t the only field in which he has wreaked havoc.

Previous decades gave lovers of aviation literature such giants as Saint-Exupery, Nevil Shute, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Beryl Markham, and Ernest K. Gann. The 1970s gave us Richard Bach. Read his books and you’ll be hard-pressed to say which had the more negative influence on aviation fiction, D.B. Cooper and his ilk or Richard Bach and his dreck. In any case, although he wasn’t quite the bestselling author that Bach was, a true giant – or near-giant – did indeed appear on the aviation-literature radar in the late 1960s and produce some of the best pop-fictions ever written about commercial aviation, although he tended to be overshadowed not just by Bach but also by his own baby brother.

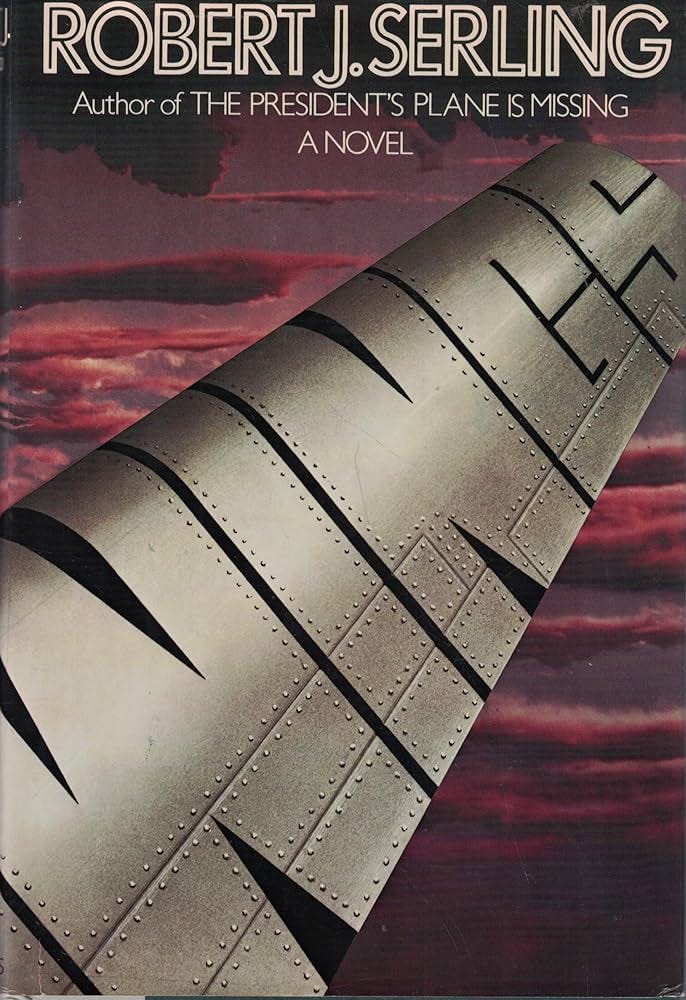

Robert Jerome Serling was born in Cortland, New York, in 1918, just fifteen years after the Wright Brothers first flight. He grew up in the same era as American commercial aviation, and he became far and away its best chronicler, both in fiction and nonfiction. As Robert was approaching his seventh birthday, his parents welcomed a new child into the family. They called this baby Rodman Edward. To generations of American fantasy and science fiction fans, he is known simply as Rod Serling, the creator of The Twilight Zone, Night Gallery, and the author of many memorable teleplays. Robert isn’t nearly as famous as Rod, but he probably ought to be. For many years he covered the aviation beat for United Press International. His first book, The Probable Cause, was a non-fiction exploration of all the various factors involved in airplane crashes. Six years later, it occurred to him that The President’s Plane Is Missing would make an excellent title for a thriller novel. His editor at Doubleday & Company agreed and advanced him a year’s salary so that he could quit his job with UPI and spend full time writing the novel. The book was published in 1967 and spent 23 weeks on the New York Times bestsellers list. At one point it shared space on that list with Arthur Hailey’s Airport, another aviation thriller, and Fletcher Knebel’s Vanished, another thriller about a politico who has gone missing. The paperback edition went through several dozen reprints in the first few years after its publication. The book’s prose was workmanlike, as is the prose of many a journalist-turned-novelist. The story was good, but as noted, it shared shelf-space with plenty of other political and aviation-related thrillers. What set Serling’s book apart was the author’s deep and detailed knowledge of not just aviation, but specifically Air Force One, the official airplane of U.S. presidents. As fiction, the book is above average. But as a collection of fascinating facts about presidents and airplanes it is riveting. One of the book’s main characters is Rod Pitcher, an aviation reporter clearly based on the author himself. Here he is passing along a key fact to an associate:

“Air Force One is what Air Traffic Control calls any plane carrying the President,” Pitcher explained. “It’s Air Force One no matter what he uses – even a little Cessna would be Air Force One if the President was aboard.”

Elsewhere he tells stories about the first Air Force One, created for Franklin Roosevelt and dubbed The Sacred Cow by the Press:

Its fuselage number was 78. Its factory serial number was 7471. It entered the Douglas assembly line in Santa Monica, California, in October 1943 – at first identical to the 77 DC-4s that had preceded it down the assembly line.

But one day that month a classified telegram was flashed to the Douglas plant. Fuselage 78 was removed from the regular assembly line and taken to a heavily guarded area. Workers quickly noticed that an unusual number of inspectors were on hand to watch Fuselage 78 metamorphose into a real airplane. They were also curious about some unique blueprints which called for installation of a battery-operated elevator in the rear of the plane…The elevator was more than an item of convenience. It was the brain child of the Secret Service, which told Douglas that on previous air trips involving conventional planes it had been necessary to construct bulky, no-step ramps to aid the polio-crippled President in deplaning and emplaning. Such ramps, the Secret Service felt, were a dead giveaway to FDR’s presence and in wartime this was intolerable. The elevator would make it not only easy to lift the President from ground to cabin level but would also eliminate the telltale ramps.

On June 12, 1944, AF-7451 officially became a member of the armed forces and also became the first airplane in history to be assigned to the White House. The Army tried valiantly to pin the title of Flying White House on AF-7451, but reporters began calling it the Sacred Cow and the less dignified name stuck…

Some of the true stories related in The President’s Plane Is Missing wouldn’t have been out of place in The Skies Belong To Us, such as the time that Lyndon Johnson flew aboard Air Force One to a Miami fundraiser. The flight was “turned into a nightmare,” according to Serling, “when the FBI relayed to the Secret Service a tip that a Cuban pilot would try to ram or shoot down the presidential jet. The Boeing that normally was used as Air Force One was yanked off the trip and replaced by another 707, without the presidential seal and with all the markings including the aircraft serial number painted out. Flighters flew a protective cover above the transport and the landing was made at Palm Beach instead of the announced destination of Miami. The return trip involved a secret take-off at dawn from Homestead AFB.”

The Serling brothers were close. Robert served as Rod’s technical advisor on the script for The Odyssey of Flight 33, a Twilight Zone episode about a commercial aircraft that travels through time to a prehistoric era (Robert, whose knowledge of aviation was encyclopedic, noted to an interviewer that the first in-flight movie ever shown on an airplane was a 1925 silent film version of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, also about a voyage to a land where dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures still roam). The story was pure fantasy but professional airline pilots wrote in to compliment Rod on the authenticity of the cockpit chatter and other details. In 1966 Robert again acted as Rod’s technical advisor, this time on a made-for-TV movie called The Doomsday Flight. It’s the story of a commercial airliner with a bomb on board, wired to an altimeter. If the airplane drops below a certain altitude before a ransom is paid to the mastermind of the caper, the plane will explode. The movie aired on NBC in December of 1966 and was the most-watched TV movie ever up to that time. But both Serlings ended up regretting their participation in the project, which inspired several real-life copycat crimes. The Federal Aviation Administration eventually urged TV stations in America not to rebroadcast the film. Rod told reporters, “I wish to Christ that I had written a stage coach drama starring John Wayne instead.”

Rod published several collections of short stories based on episodes he had written for both The Twilight Zone and Night Gallery. He rarely bothered to dedicate these slender paperback volumes to anyone. But the very first of them, Stories From The Twilight Zone, is dedicated: “For my brother Bob, the first writer of the Serling Clan.”

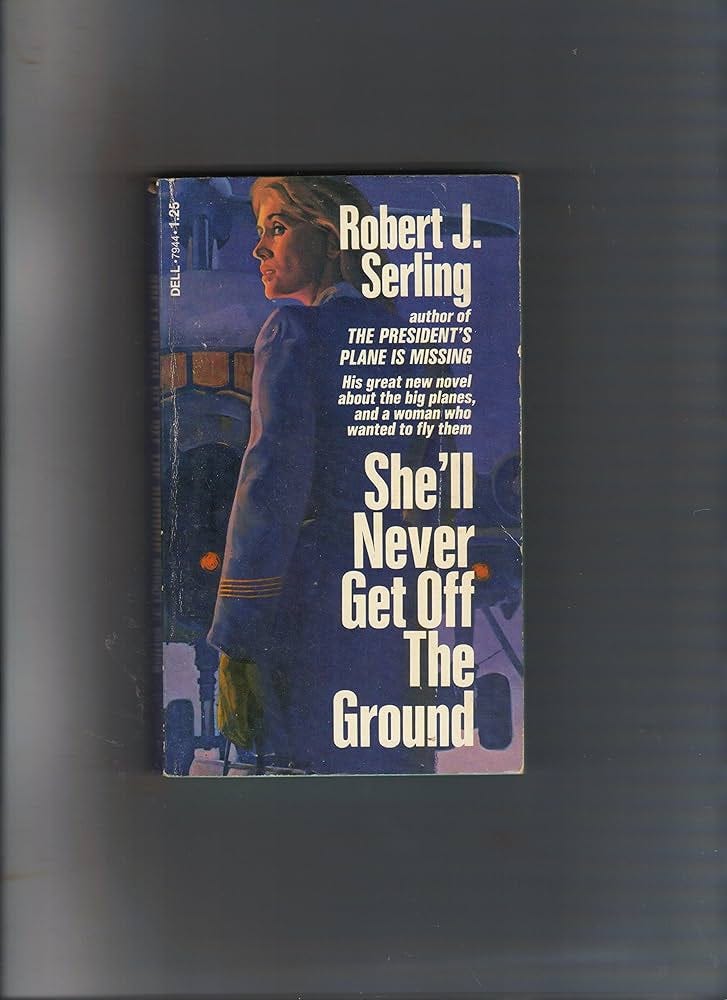

Although he turned out plenty of thrillers, Robert’s best novels were his less sensational tales of life in the commercial aviation industry. My two favorites are 1971’s She’ll Never Get Off the Ground and 1982’s Stewardess. Both of these are straight-out feminist in their aspirations, which is surprising because, though Rod was a very liberal Democrat, Robert was a rock-ribbed conservative Republican. The first of these tells the story of Dudney Devlin, a young woman with experience flying cargo planes in Alaska who is now attempting to become the first American female to qualify as a commercial airline pilot (she was accepted into Trans-Coastal Airline’s training program by mistake because of her male-sounding name). The character was partially inspired by Turi Widerøe, a Norwegian woman who, in 1969, became the first woman to work as a pilot for a major commercial airline (Scandinavian Airline Systems). Serling, who was not a pilot (weak eyesight disqualified him), spent six weeks training at a school for Boeing 737 pilots in order to accurately describe the grueling training routine Dudney Devlin would have received once she was accepted into the program. The book is ferocious in its criticism of sexism in all its guises, although contemporary feminists would probably, and justifiably, spot some lapses in Serling’s feminism (he was born in 1918, remember). Because She’ll Never Get Off the Ground was written near the apex of the Golden Age of hijacking, Serling seems to have felt obliged to acknowledge it. Dudney at one point finds herself on a flight being hijacked by a madman armed with a gun. But Serling clearly is more interested in the mundane facts of daily airplane life than he is in crazed gunmen. The hijacker, Peter Hoffman, is introduced on page 292 of the paperback and is killed by one of the passengers (a Marine with martial arts training) on page 299. Curiously, the book was published in early 1971 but the hijacking it describes takes place in November 1971, the very month that D.B. Cooper’s actual hijacking took place. Both hijackings take place in the American West on smaller regional carriers. And both hijackers (presumably, in Cooper’s case) died in the attempt. I was disappointed in the conclusion of this novel, but I won’t spoil it for you by revealing it.

Stewardess is my favorite of Serling’s novels and probably his best. It’s a historical novel that begins in 1955 and tells of young Danni Hendricks’ rise from stewardess trainee, to actual stewardess, and then into airline company management. Written about ten years after She’ll Never Get Off the Ground, it represents a major leap forward in Serling’s development as a feminist. In that earlier novel, Serling depicted some horrific behavior on the part of various male airline employees (particularly a pilot named Crusty Calhoun), but would often then try to soften the blow by insisting that, outside of their own realm of aviation, most of these men behaved perfectly decently to women, which seems like small consolation. In Stewardess he seems much less inclined to forgive sexist behavior. This book feels more personal, probably because, from 1968 until her death in 2000, Serling was married to Priscilla Arone Serling, a former airline stewardess. No doubt many of the nightmarish episodes in Stewardess were told to Robert Serling by his wife. Danni experiences plenty of sexual harassment, most of it from male co-workers, particularly pilots. But her mistreatment goes beyond sexual harassment. At one point she is raped by a pilot, and Serling doesn’t flinch from the horror of it. Although he was married to an expert on the flight attendant’s life, Serling nonetheless did the type of full-immersion research for which he was famous. He was accepted into an Eastern Airlines school for flight attendants (Class of 1981) and stuck it out “from start to graduation.” The research pays off. The book reads almost like non-fiction. Readers with no inherent interest in aviation will find little to enjoy here. It’s not a thriller and there are no hijackings or mad bombers. But if you want to know what it was like for women who worked as flight attendants in the 1950s and 60s, this will prove to be an illuminating experience.

Also worth mentioning is McDermott’s Sky, published in 1977. This was the first novel Serling published after his younger brother’s death, at age fifty, in 1975, and Rod seems to have been on his mind as he wrote it. The protagonist of the story is Max McDermott, a so-called “check pilot.” An experienced senior pilot, his job is to ride along in the cockpit and evaluate other pilots who work for the same fictional airline, Coastal Airways. Each pilot needs to have his skills re-evaluated every six months or so. McDermott was a young police detective before World War II broke out. He was trained as a pilot during the war. Afterwards he became a commercial aviator. The novel, one of Serling’s more commercial efforts, is set in 1971 and involves the murder of a beautiful Coastal Airways stewardess named Rebel Martin. It seems almost certain that she was killed by a co-worker (she was sleeping with several of them) and so the police enlist McDermott – who is familiar with both airline procedure and the investigation of murders – to help them find the killer. The novel begins with a very short prologue which sounds eerily like one of the introductions Rod Serling delivered before each installment of Night Gallery. It begins:

They still talk about a stewardess named Rebel Martin – in crew lounges, on layovers, in cockpits, and in the homes and apartments of airline people who knew her.

It concludes in much the same fashion:

Most of all the stewardesses think of Rebel on dark, lonely nights, when strange creaks seem like the lurking steps of an unseen invader and when imagination distorts every shadow and sound into terror.

The novel is a good but fairly routine murder mystery that can’t quite live up to Serling’s description of it as a tale of terror. What elevates it above thousands of generic murder mysteries is, once again, its insider knowledge of airline procedure. A reviewer for the Houston Post wrote: “Take Hercule Poirot and stick him in the middle of Arthur Hailey’s Airport and you have…McDermott’s Sky.” And the allusions to Rod Serling don’t end after the prologue. Amusingly, Serling works his baby brother’s anthology TV series Night Gallery into the plot (which is probably why he set the story in 1971, when the program was still running on network TV). A police report on the activities of Robert Denham, one of Rebel Martin’s lovers, on the night of her death reads:

Claimed he did not see her night of murder, that he went bowling with his regular team, watched TV when he got home, and went to sleep around 1:30 a.m. Said he watched most of a program called ‘Night Gallery,’ and then the news and Dick Cavett. Gave me the plot of two episodes on ‘Night Gallery’ and the names of three guest stars on the Cavett show. These checked out.

Later it will turn out that Denham lied about watching Dick Cavett’s talk show but not about Night Gallery, which aired earlier. This will destroy his alibi for the time of the murder.

McDermott’s Sky is slight, a bit of a bauble. The following year Serling would publish Wings, probably his most ambitious novel, a saga that follows the birth and growth of a great American commercial airline from the 1920s to the 1970s. In the 1980s, after publishing Stewardess, something happened to Serling’s fiction. More and more it seemed as though it were being written by Rod, not Robert Serling. In 1985 he published Air Force One is Haunted, a supernatural sequel to The President’s Plane is Missing wherein the ghost of FDR haunts a contemporary president whenever he flies aboard Air Force One. In 1990 he published Something’s Alive On The Titanic, a ghostly thriller set deep under water rather than in the friendly skies. In a 1991 interview with the Associated Press, Serling noted that, “The last two books are the kind of books Rod would have written. There are times when I wonder if Rod is putting some of these stories in my mind. I know it sounds screwy.”

Robert Serling may have taken on some of Rod’s occult interests late in his career, but fortunately he eschewed most of Rod’s self-destructive habits, such as smoking four packs of cigarettes a day even after suffering a heart attack (Rod’s frightening indifference to his own health is detailed in his daughter Anne’s fine memoir As I Knew Him: My Dad, Rod Serling). Born nearly seven years before Rod, Robert outlived his baby brother by 35 years. He died, at 92, in May of 2010. He was probably the last of the great aviation novelists who were old enough to remember when commercial aviation was in its infancy. He came of age when much of the aviation fiction being written had nothing to do with hijackers, terrorists, and ransom demands. But all of that changed forever on November 24, 1971, when D.B. Cooper opened up the rear exit of an airplane flying over southern Washington state and then, for all we know, stepped out into The Twilight Zone.

![Death in the Clouds: A Hercule Poirot Mystery: the Official Authorized Edition [Book] Death in the Clouds: A Hercule Poirot Mystery: the Official Authorized Edition [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!x3Ce!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd0329c21-bd11-4fb7-8877-500822235a1c_183x276.jpeg)

Monty Python did a bit where a hijacker tried to disrupt a plane flight so he could get off in the town of Luton in England. Eventually, he gets dropped off (with no casualties) to take a bus to Luton- only to have a stereotypical looking hijacker demand the bus go to Cuba instead. Which it does!

I wondered what that was about when I saw it, but, as you noted how common it was for Cuba to be a hijacker desire, it makes more sense.

I note with sorrow the death of Freddy Forsyth today. Reminded my to return to this blog.