FORTY PAGES TO GO

My favorite part of a novel? Roughly forty pages from the end. Every novel is different, of course. Some, such as Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn and William Kennedy’s Quinn’s Book, have superb opening chapters that they never quite live up to. Both Of Human Bondage and East of Eden have dull beginnings (especially East of Eden, which begins back in the ice age and describes how glaciers formed California’s Salinas Valley) and tediously drawn out endings, but both books are enlivened by long, tremendously fascinating middle sections that make the reading experience worthwhile. The same could also be said of War and Peace, which starts slowly and seems to take forever coming to a conclusion, but has lots of interesting stuff in between. For the most part, however, if a novel follows a fairly conventional – or, if you want, classical – story arc, its final forty pages are, in my opinion, the most fun to read.

Some might say that this final 40 pages is merely the climax of the book and that a climax is logically a pleasing phenomenon to any human being. But I think it is about more than just the plot reaching its climax. I like to think of this part of the book as the last three or four miles of a marathon or – if you run 10Ks rather than marathons – think of it as the last K. It’s that point in an endurance event where you know that you will finish and you feel fairly certain you will enjoy the experience. Some 10Ks – especially if they are run in foul weather into the face of a headwind – can be miserable experiences from start to finish. The same is true of some books. Many endurance runs start out daunting. This is true of the famous Dipsea Endurance Run, an annual event since 1905 which begins in Mill Valley, California. You start out by climbing three flights of stairs comprising a total of 672 steps – roughly the equivalent of running to the top of a 52-story building. I ran the race, just once, back in the 1980s. By the time I reached the 672nd step, I was seriously doubting the wisdom of entering the run. After the stair climb, numerous challenges remained: a steep descent into the Muir Woods, a tortuous crossing of rocky trails with names like “Cardiac” and “Dynamite,” and another steep ascent known as “Insult Hill.” Somewhere along the way, however, this run ceases to seem merely arduous and somehow transforms itself into an almost sublime experience. Near the end, as tired as I was, I found myself eager to prolong the experience, unhappy about the idea of reaching its conclusion. While most runners begin to sprint towards the end of a race in order to improve their race times, I usually slow down a bit, in order to forestall the end of an enjoyable experience. Likewise, there comes a point in many good books where I don’t want to pick the book up. I am enjoying the story, I like thinking about the characters and their dilemmas, and I am not overly eager to see it all end. This, I think, is the best experience reading has to offer. Yes, I love fast-paced thrillers that keep me turning the pages rapidly and speeding to the end. But even better, in my opinion, is the book that makes you not want to speed to the end, but rather makes you want to savor that final sprint, maybe even slow it down to jog. For me this usually happens about forty pages from the end of a book. I’m talking primarily about fairly modern novels, novels whose length is somewhere between, say, 150 pages and 400 pages. In triple-decker Victorian novels by Dickens or Trollope or Eliot, you may find yourself intentionally slowing down with a hundred or more pages to go. The longer the book, the longer the final stretch. But if, like me, you read a lot of novels in the 250- to 400-page range, then you will probably find that it is usually about forty pages from the end of a good novel that you begin forcing yourself to read more slowly, resisting the urge to pick up the book until you can read it without distraction.

Novels, generally, are not spontaneous artistic outbursts and they cannot be enjoyed as such. They are not cave paintings, which may have been sketched in an hour or two only to go on fascinating observers for thousands of years. They are not poems, such as “Kubla Khan,” which can be scribbled out in a few minutes during a burst of sudden creativity (with or without opium). The novel is a fairly recent development in human history, and a bit of an unnatural one. For millennia, stories rarely lasted longer than a single comfortable sitting would allow. Even movies and TV shows, for all their technical complication, would seem to have more in common with storytelling’s roots than novels do. Novels, even very enjoyable ones, are always a test of one’s endurance. And in every successful test of endurance comes a moment when one realizes that a) one is going to make it to the end, and b) the end is going to be enjoyable. In a marathon or a 10K, one can’t realistically come to a dead stop a mile or two from the end and put off the conclusion in order to savor it. To do so would be to destroy the continuity of the experience. But rarely does one read a novel straight through in a sitting (I’ve done it maybe ten times, and always with a fairly short novel, such as Tom Perrotta’s Election or James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity). A novel is a test of endurance in which stopping now and then is pretty much a requisite. Usually, my stopping points are fairly random, dictated by how tired I am or how much reading time I have at my avail. I supplement my writing income by working as a freelance notary public. I often find myself sitting in the waiting room of an escrow company or real estate firm with twenty minutes to kill until my next notary appointment. Frequently I kill this time by reading a novel. But I never bring a novel with me that has entered that juicy final forty pages. I don’t want to read that part of the book if there is any other claim on my time, or any chance I’ll be interrupted before the end. When I realize that I have once again found a novel with a promising final forty pages, I always put off finishing it until I am alone and have no distractions ahead of me.

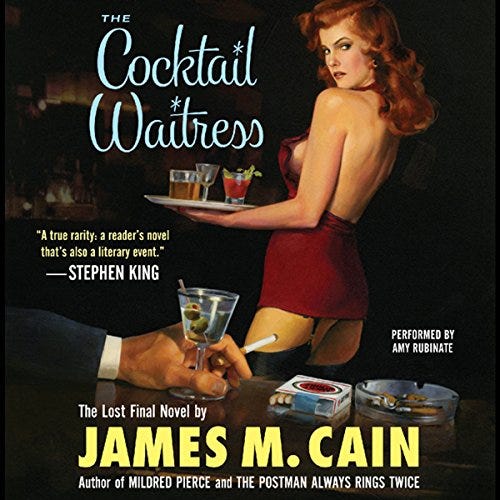

Recently I read The Cocktail Waitress, a James M. Cain novel that was left to languish in the cabinet of his agent’s office after Cain’s death and was not published until 2013. Though it is not the equal of Mildred Pierce or The Postman Always Rings Twice, the book was nonetheless an absorbing and, for me at least, very satisfying read. The story concerns a gold-digging cocktail waitress named Jane Medford who may or may not have killed her first husband and may or may not be planning to wed and kill another man. The hardback book is 254 pages long. On page 213 (41 pages from the end) a very interesting (and kinky, as befits a Cain novel) development occurs. Jane Medford (now Mrs. Earl White II) answers the door of her husband’s mansion and finds herself face to face with a prostitute/masseuse dressed in a nurse’s uniform who has come to give Jane’s husband a hand job (Jane won’t sleep with him, so a hand-job-for-hire is the only way Earl, who suffers from angina and can’t engage in traditional intercourse, can relieve his sexual urges). At this point I wanted to slow down and delay arriving at the end of the book. It became clear here that Cain was going to make the climax of his story as down-and-dirty as his imagination and the mores of mid 20th century publishing would allow him to. Sure, much of the writing in the book seemed as if it could use some additional polish. Yes, the plot was often preposterous and some of the characters were made of cardboard, but this was nonetheless a good old-fashioned fifties-style pulp novel in which a master of the genre was clearly trying to push the boundaries of sexual explicitness. I had every confidence that Cain was about to deliver a conclusion that, if nothing else, would be wildly entertaining. And I was right. A few hundred words after the arrival of the “nurse,” Jane is in a cocktail bar when she gets a call from her housekeeper informing her that Mr. White has suffered a serious heart attack as a result of his masseuse’s manual manipulations. “Get out here, Miss Joan,” the housekeeper tells her, “He’s bad off this time – real bad.” I was on page 215 when I read those words, 39 pages from the end of the book. It was late at night, the ideal time to read a noir thriller, but though I could have finished off the final 39 pages fairly easily before going to bed, I decided not to. I wanted to savor the ending of the novel. I knew it would be juicy and salacious and I didn’t want to rush through it. I put the book aside and went to sleep. I decided to finish reading it the following night. That would give me an entire day to ponder what might be coming in those final 39 pages.

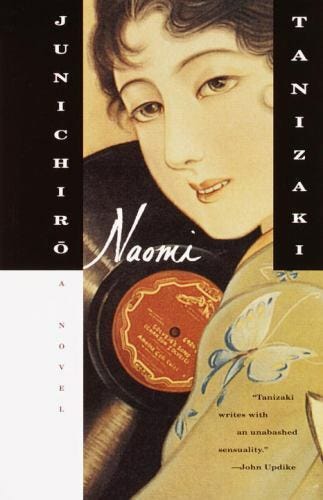

A few weeks before reading The Cocktail Waitress I read Junichiro Tanizaki’s novel Naomi. The book is what Lolita might have been if it had been written by James M. Cain and set in Japan in the 1920s. It’s the story of 28-year-old Joji, a boring corporate drone, who becomes obsessed one day with a beautiful 15-year-old café waitress (not, alas, a cocktail waitress, but close enough) and sets out to transform her into a lady in somewhat the same way as Henry Higgins sets out to refine Eliza Doolittle in My Fair Lady. Unfortunately, the sweet-looking and virginal Naomi doesn’t remain a virgin for long. Nor is she ever all that sweet. She allows Joji to woo her and, eventually, marry her only because she is hungry for the material things she can buy with his money. Joji tries to rein in her appetites for sex and shopping, but with little success. Naomi becomes a monster of greed and lasciviousness. After draining Joji’s bank account, she leaves him and goes in search of other men to sleep with and sponge off of. Even then, however, Joji is determined to win her back, still believing that she can be made into a proper lady if she is given enough love and instruction. On page 193 – 44 pages from the end of my 237-page paperback edition of Naomi – Joji receives some devastating news. Up to this point he believes that Naomi has been unfaithful to him with only two other men. Now he learns otherwise. Abandoned by Naomi, Joji has sought out Hamada, one of Naomi’s young lovers, to find out what has become of her. Hamada tells him, “There’s no telling how many times you’ve been disgraced behind your back…When you were in Kamakura last summer, how many men do you think Miss Naomi had?” Joji answers, “I know about you and Kumagai. Was there someone else?” And Hamada tells him. “Don’t be startled Mr. Kawai…Seki and Nakamura too.” Stunned, Joji responds, “You mean the whole group, every one of them?” “Yes,” answers Hamada. “Was Naomi manipulating them,” asks Joji, “so that they didn’t know about each other?” “No,” says Hamada, “Sometimes two of them would even run into each other” on their way in or out of her summer abode. “They were tacitly in league with each other. They shared her.” This shocking info sends Joji into a tailspin. By this time we are on page 198, exactly 39 pages from the end of the novel. As a reader I found myself eager to know what Joji would do next. Would he seek out Naomi and kill her? Would he kill himself? Would he swear off his obsession with Naomi once and for all and get on with his life? Would Naomi hit rock bottom and come crawling back to him? If so, how would Joji respond? In mid book, the plot might go just about anywhere. With 40 or so pages left, the options are limited, which makes them more thrilling to contemplate. Early in the book, it was still possible to believe that Naomi might reconcile herself to loving just one man for the rest of her life and decide to be faithful to Joji. With 40 pages to go we can scratch that possibility from our list. Though I was eager to see where Tanizaki’s plot was leading, I put the book aside at this point. I wanted to savor the possibilities for awhile.

Shortly before reading Naomi, I read Irene Nemirovsky’s lurid sex-and-murder drama Jezebel (Yes, I like lurid sex novels; so sue me!). The Vintage paperback is 199 pages long. The title character (whose name is actually Gladys) is in a bind. For years, her beauty has allowed her to trick people into believing that she is much younger than her real age. She has also fooled people into believing that her daughter died at age 14, when in fact the daughter was closer to 20 and had just given birth to a son. When the daughter died, Gladys, unwilling to face being a grandmother, bribed a working-class family to take away her grandchild and raise it as their own child. But the grandson has grown up and learned his true identity. He has discovered Gladys’ whereabouts and is threatening to reveal her many secrets to society (that she was responsible for her daughter’s miserable demise, neglected her own grandchild, and is much older than she claims). This will almost certainly ruin Gladys’ chances of marrying the handsome but penniless count Aldo Monti who is bewitched by both her beauty and her money and can offer Gladys a secure position in society. Monti is 36. He believes Gladys to be about 45. She is actually closer to 60. Will he still want her if he finds out her actual age? In Chapter 17, which begins on page 161 – 38 pages from the end of the book – Gladys’ grandson begins really turning the screws. He wants money. He wants recognition. And he wants revenge. By this time, Gladys’ options have begun to narrow. Will she murder her own grandson? Can she successfully buy him off? If she goes to Count Monti and confesses her age, will he still love her? At this point in the book, I put it aside to relish the pleasure of Gladys torment (she is a thoroughly unlikable character) and to try to guess which of the dwindling options available to Gladys the author would choose for her. (Generally, as a protagonist’s options narrow, his plight becomes more engrossing.)

I could cite dozens more examples of this forty-pages-from-the-end phenomenon. Sometimes the phenomenon occurs sixty pages from the end, sometimes 20. Sometimes it doesn’t happen at all. For me however, due to some correlation between the length of the novels I tend to read and the point in a story where I find myself eager to stretch out the reading experience, about forty pages from the end seems to be my favorite part of a novel, the point where I am eager to keep reading but don’t want the book to end. Often I will find myself in this paradoxical situation and only then will it occur to me to see how many pages the book contains. More times than I can remember, I have flipped to the end to find that I have 40 pages remaining, or 41, or 39. That general neighborhood seems to be my sweet spot as a novel reader.

Of course I don’t always make it to that point in a novel. Plenty of times I will abandon a novel after fifty or a hundred or two hundred pages. If I’m a quarter of the way through a book and it isn’t thrilling me in some way, I’ll generally put it aside (John Updike once said, “At some level, every novel aspires to be a thriller” or words to that effect; and I believe that every novel should at least try to thrill its readers). I’ve given up on novels after reading to the halfway point and even a bit beyond. But I’ve never quit a novel that I was 40 pages from the end of. At that point, it’s a sure thing that I will finish the book. If it is only a so-so book, I won’t bother putting the book aside in order to draw out the pleasure to be derived from reading those final forty pages. I’ll just finish up the book and move on. For me, one sure sign of an author’s skill as a storyteller is his ability to get me to slow down and savor those final forty pages. Not everyone can do it. Generally it takes a master craftsman such as Cain or Nemirovsky or Tanizaki. Most recently it happened while I read Naguib Mahfouz’s Cairo Modern (another novel in which sexual betrayal figures prominently).

If you are an avid fiction reader, it is likely that you have experienced this phenomenon yourself without really noticing it. To find out if my theory about the last forty pages is correct, go to your bookshelves now and take down four or five of your favorite novels, preferably novels in the 250- to 400-page range. Flip to a place roughly forty pages from the end of the book. Start reading from there and see if you find yourself once again falling under the author’s spell. If, like me, you happened to be blessed with a horrible memory and can’t recall how a book ended two months after reading it, you may just find yourself racing through those final forty pages to learn once again how it is all going to end. Generally, if a novel is really good, rereading its final forty pages will be enough to remind you of why you enjoyed it so much. Just as I rarely read a book in one sitting, I rarely re-read a book, even those I really love. I’ve re-read maybe ten novels in my life (I re-read Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye every ten years or so just to see if perhaps I’ll finally find myself enjoying them; so far it hasn’t happened with either book). But fairly often I will pick up a favorite book and reread its last forty pages or so, just to bring the thrill of the original reading experience back. It’s kind of like eating a bit of cold turkey from the refrigerator three days after Thanksgiving. Just a bite of it will help you conjure up the memory of all the pumpkin pie and stuffing and gravy and mashed potatoes which brought you such pleasure a few days earlier. You don’t need to re-eat the whole meal in order to experience a brief reminder of how great the feast was.

If you are a novelist, you might want to give some thought to this forty-pages-from-the-end phenomenon. That’s the point at which your readers’ curiosity about how the story will conclude ought to reach terminal velocity. If you force the reader to begin his stretch run too early – seventy pages from the end, say – he may grow fatigued before reaching the final page. If you save the stretch run for the last ten or fifteen pages, he won’t have enough time to savor it. Every reader is different, but if you want to make a lifelong fan out of me, start your novel’s stretch run about forty pages from the end of the book. Reviewers are always praising books for being unputdownable. Me, I want a book that begs to be put down forty pages from the end in order to savor the anticipated pleasure those last forty pages are likely to bring.