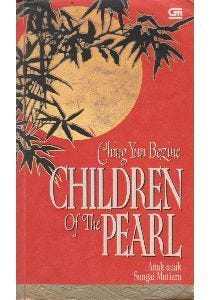

It is curious how American popular culture can produce a novel as fine as Children of the Pearl, by Ching Yun Bezine, and then largely ignore it. The novel, a paperback original (meaning it was never published in hardback) was published by Signet in October of 1991. Though “only” 399 pages long, the story has an epic sweep. It follows four Chinese teenagers as they leave behind their small town alongside China’s Pearl River and make their way to The Land of the Golden Mountain, which is what Chinese peasants called America. Believing that easy riches await them in America, where the streets are reportedly paved with gold, three young men – Fachai, Loone, and Quanming – and a young woman – Meiping – sign contracts with a labor trader, who pays their way to America aboard a ship full of other desperate characters. Fachai is a recently married man of 18 or 19. He and his father make a living fishing the waters of the Pearl River. But when their boat is destroyed, Fachai, who has recently married the love of his life, finds himself in need of money. He signs a contract with the labor trader in the hope of making a quick fortune in America and then returning to his beloved wife in the small Chinese town of White Stone. Quanming, whose brother was beheaded by the government for advocating human rights, wants to forget his many miseries, including the beautiful young Kao Yoto, who broke his heart by marrying another man, and find his fortune in America. Loone is an angry young man with a gift for painting and drawing. His parents have both died. All he cares about now is his art, and so he allows his uncle and aunt to sell him off to the labor trader. Loone figures he can paint and draw in America as well as in China. Sixteen-year-old Meiping is the daughter of a man and wife who run a small restaurant. She is tall for a Chinese girl, nearly six-feet, which makes her practically unmarriageable in China, where men do not want a wife taller than they are. She fights with her father constantly, so when the labor trader offers her a chance to start anew in America, she willing signs up.

What none of these four young people understand is that the labor trader is basically selling them into slavery. When they arrive in San Francisco, Meiping will find herself consigned by the labor trader to a whorehouse in Chinatown, operated by a ruthless Chinese-American businessman. Fachai was told by the labor trader that he would be allowed to work aboard a big modern fishing boat in the waters off San Francisco. Instead he will find himself working in a crowded and smelly factory that processes fish that have already been caught. He will work ten hours a day, seven days a week, gutting dead fish and cutting off their heads. He will never be allowed to work as a fisherman. Quanming will do slightly better than Fachai and Meiping. He will be apprenticed to a wealthy Chinese-American businessman in Chinatown. But before he can rise up the corporate ladder, he will have to spend years learning the English language and the ways of American business. He will fall in love with a beautiful young Caucasian girl, the sister of his English tutor, but neither his Chinese acquaintances nor the local Caucasian community will countenance this relationship. And Loone, the artist, will live above a Chinese restaurant owned by a kindly Chinese married couple. They treat him like a son but he has no interest in learning the restaurant business. All he wants to do is paint.

The story begins in 1912 and concludes around 1936. The characters will find love and lose it, experience triumphs and disasters, marriages and betrayals, and along the way lose touch with their Chinese roots, while never being truly accepted as Americans by the native-born community. This is a novel that moves swiftly and is filled with interesting characters and events. It is also well written and intelligent. I cannot fathom why its publisher didn’t treat it like a potential mega-bestseller and give it a large hardback release followed by an author tour, perhaps including some appearances on TV talk shows. Instead it got dropped quietly into the waters of the book world and barely made a splash. Which is a shame, because Ching Yun Bezine’s life story is at least as interesting as the book itself, and had it been written about in popular venues such as People magazine or The New York Times Magazine, she might have become, if only briefly, a celebrity author. As it happened, the press barely paid any attention to the book or its author. Fortunately, one newspaper (The Chicago Tribune) published a long (1700 words) and detailed profile of the author, by reporter Norma Libman. I found this profile online, and it reads like a thrilling short story.

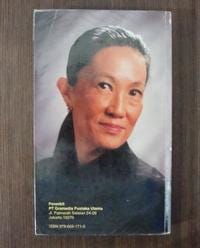

Ching Yun Benzine (pictured above) was born in 1937, in Ching-dau, near Beijing. According to Libman’s profile, Ching was “the ninth and youngest child of a woman who had successfully fought the ancient Chinese tradition of binding feet when she was a girl.” Alas, Ching’s mother wasn’t entirely against tradition. She arranged for her daughter to marry a doctor rather than allowing young Ching to make a love match of her own. Likewise, although Ching wanted to study the arts, especially dance and literature, her mother insisted that she pursue a more practical law degree, which Ching did.

Here’s more from the Chicago Tribune profile:

“By the time I was born,'' says Bezine, telling the story of how her rebellious mother became such a strict parent, ''my mother was 40. She had forgotten that she was once a young fighter. Now she wanted to raise her children as her parents had tried to raise her. So they raised me, especially, since I was the last one, in the old-fashioned way.''

When the Communists took over China in 1949, Ching and her family moved to Taiwan. She graduated from a Taiwanese law school in 1960. And it was then that her parents forced her into a marriage with a young doctor with whom she was not in love. Seeking an escape from a smothering marriage, she applied for scholarships to schools in the United States. She was still hoping to pursue an education in the arts. She got an acceptance from Blue Mountain College, in Mississippi. At first her husband objected to her plan to go to America, even though his own parents lived in Los Angeles. Eventually he relented, thinking it might be helpful to have additional family members in America, in case the Communists should take over Taiwan as well. So Ching was allowed to travel to the U.S. Not until she arrived in Mississippi, however, did she discover that she was pregnant. She was residing at a rural girls’ college in the deep South and had no husband with her, so when it became clear that she was pregnant, life became difficult for her. Reluctantly, she left school and moved to Los Angeles to stay with her in-laws until the baby was born. Alas, her in-laws were furious with her for leaving her husband in Taiwan. They were even more angry when the baby, born in 1962, turned out to be a girl. They wanted a grandson. Ching wanted to take the baby and leave her in-laws, hoping to once again seek out a college where she could study the arts. The in-laws told her she could leave, but she couldn’t take the baby with her. Ching told Libman that, if the baby had been a boy, she would have divorced her husband and gone back to college and left the boy with his grandparents. She knew that they would have taken good care of a grandson. But she feared a daughter would be treated no better than a servant. So she remained in her loveless marriage for 12 years. Her husband eventually moved to the U.S. and set up a thriving medical practice in Kentucky. He also cheated on Ching with a variety of mistresses. He kept a mobile home parked on their property in which he kept his favorite mistress. Ching drowned her sorrows in education, earning a bachelor’s degree from Brescia College, in Owensboro, KY, and a master’s degree from Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green. During those years she wrote fourteen novels in Chinese, all of which were published in Taiwan. Although the novels became successful throughout Southeast Asia, she was paid very little for them and collected no royalties.

In 1972, she was teaching at an elementary school in Bowling Green when she and her husband were finally made naturalized citizens of the U.S. At the naturalization ceremony a judge spoke about all the freedoms that the new citizens were now afforded as Americans. But Ching realized that she had no freedoms at all; she was entirely under her husband’s thumb. She broke down and cried in the courtroom during the naturalization ceremony. Three days later, she took her two children, ages ten and seven, and visited a divorce attorney. Here’s how Libman described what happened next:

Bezine explains that to her in-laws, who followed old traditions, a daughter-in-law is property and if she remarries, their ancestors will ''cry in heaven.'' She had to agree in writing never to marry again, and her in-laws moved in with her so they could watch her. Still, at this point, Bezine says she felt free because she no longer had to go to bed with a man she didn`t love. The family moved to Nashville, and Bezine began to attend George Peabody College (now a part of Vanderbilt University), working toward a Ph.D. in international and comparative education. It was here, in 1974, that she met Frank Bezine, an American psychologist and educator and a guest lecturer at the school…After they had known each other a short time he came to her house and told her in-laws, with the help of a translator, that they had to get out of her house, that they were no longer her in-laws, and that he was courting her and wanted to marry her.

She resisted at first, even leaving the school, because Frank Bezine was still married at the time. In 1975 he was divorced and the two were married later that year.

Alas, although Ching and her new husband wanted to raise her children in their household, her ex-husband wouldn’t allow it. She had to leave the children behind when she married Bezine, and even in 1992, when her children were ages 30 and 27 and living on their own, they refused to have anything to do with their mother. Their hearts had been turned against her.

It sounds like something out of a tragic novel or a play. But, fortunately, it had a happier third act. After marrying Bezine and moving to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Ching, now known as Ching Yun Bezine, began writing her first novel in English, Children of the Pearl. She also became a columnist for a daily local newspaper.

Although Children of the Pearl didn’t get any kind of splashy promotion when it was published, it must have sold at least reasonably well, because Signet also published two sequels that Ching Yun Bezine wrote for it, Temple of the Moon and On Wings of Destiny. Signet also published her historical novel River of Lanterns, set in 14th-century China.

It’s odd that Ching Yun Bezine didn’t become a bestselling author. Children of the Pearl was published just two years after Amy Tan’s Joy Luck Club, which was a very successful novel and adapted into a 1993 film. Despite her novel’s success with many readers and book clubs, Tan nonetheless received a great deal of criticism from Asian-American reviewers who felt that her portraits of China and the Chinese people (especially Chinese men) were inaccurate and derogatory. Tan who was born in Oakland, CA, seemed to be not authentically Asian enough for some of her critics. Likewise, many contemporary Asian writers, such as Celeste Ng, author of Little Fires Everywhere and other books, seem to dislike the books of Nobel Laureate Pearl S. Buck. In 2010, Ng wrote in The Huffington Post:

I hate The Good Earth because, all too often, it’s presented not as a work of fiction but as a lesson on Chinese culture. Too many people read it and sincerely believe they gain some special insight into being Chinese. In one quick step, they know China, like Neo in The Matrix knows Kung fu.

It’s possible (likely, even) that critics such as Ng would not like Ching Yun Bezine’s fiction any more than they do Pearl S. Buck’s. Novelist Deanna Fei (pictured above) complained in another Huffington Post piece from 2010, about a New York City social studies textbook she encountered as a student in which the Chinese were described as a “yellow-skinned and slanty-eyed people.” I’ve seen plenty of others complaining about novels in which Asian characters are described as having slanted or almond-shaped eyes. I’ve never been sure why almond-shaped eyes are considered a derogatory trait. Chung Yun Bezine certaintly doesn’t think they are. Here, in part, is how she describes Kao Yoto, the young woman who breaks Quanming’s heart early in the novel: “a pale heart-shaped face with two dark, slanted almond eyes.” Later, of the same character, Bezine writes: “She looked at him with her slanted almond eyes, and her bow-shaped mouth curled up into a smile…”

Politically correct critics frequently complain about the way that Caucasian characters refer to Asians derogatorily in Western pop fictions set in Asia, where the natives are frequently called “chinks” or “slants.” That kind of talk is, of course, racist, but it’s not as if Caucasians are the only ones to engage in that kind of racism. In Children of the Pearl (and numerous other novels set among Asians), Asian characters regularly refer to Caucasians as “white devils,” “white pigs,” “barbarians,” “ghosts,” and worse. Caucasian women are called “white whores,” “white cows,” and “devil girls.” The Asian characters in Children of the Pearl talk about Americans with the same kind of racism that Americans of the era talked about the Chinese. Kao Yoto tells Quanming, “The white devils have transparent flesh, yellow hair, and blue eyes. They eat raw meat and walk around half-naked most of the time. We Chinese…must never put ourselves in the company of those who aren’t truly civilized!” Elsewhere, Meiping, yells at her Caucasian lover, “You white devils know nothing about tradition! You’re all barbarians.” One Chinese woman is described by Bezine as having “the look of a porcelain doll.” If a white American male had written such a description he’d likely have been accused of racism. Bezine’s novel complicates the drearily woke contemporary view about Caucasians writing about other races (i.e., that they should stay in their own lanes and not write about non-white characters). Bezine, born and raised in China, writes about slanted eyes and yellow skin without any malice or racism towards her characters. She describes one Chinese-American characters as “a greasy-faced man.” Were a Caucasian author to describe an Asian that way, he’d be automatically accused of racism. Bezine knows that there are unpleasant Asians just as there are unpleasant Caucasians, and she isn’t afraid to say so. Many of the complaints leveled at novels like James Clavell’s Shogun and Michael Crichton’s Rising Sun – i.e., that they contain a lot of unpleasant Asian characters – could just as easily be leveled at Children of the Pearl. But I doubt that Bezine is a racist. She just believes in depicting her characters, whether Caucasian or Asian, as real people, warts and all.

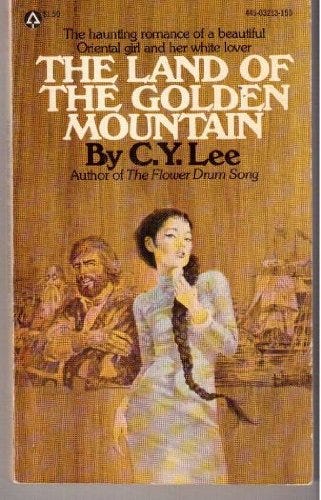

Children of the Pearl reminded me a lot of The Land of the Golden Mountain, a 1967 novel by C.Y. Lee, the author of The Flower Drum Song. Lee’s novel is also about Chinese peasants from the Pearl River area of China who migrate to California. His novel is set in 1850, near the beginning of the California Gold Rush. His novel also demonstrates that Chinese attitudes towards Americans could be as wrongheaded as American attitudes towards Chinese. On the boat taking her from China to America, his 17-year-old heroine, Mai Mai, notes that Americans, whom, like most Chinese, she calls “foreign devils,” “were supposed to be pale-skinned monsters who grew colorful hair on their chests and arms, and ate raw meat with knives and prongs, like the ancient barbarians.” She observes that the captain of the ship is a “foreign devil with a big black beard and a water-buffalo horn for a nose…” The Chinese also have many misperceptions about American Indians in Lee’s novel. Having heard them called redskins, Mai Mai, upon spotting some at Sutter’s Fort in Sacramento, “was disappointed that they were not crimson.” Her companion, Four-Eyed Dog (a name given to him by the Chinese, not the Americans), “explained that it was because they did not eat enough human heads.” Mai Mai and her companions have somehow gotten the impression that Indians scalp their enemies in order to eat the scalps. The book is full of people who make ignorant assumptions about cultures they know little about. One Chinese character warns another not to drink cow’s milk, believing that it is what puts so much hair on the chests of white men. But this doesn’t strike me as racism so much as mere ignorance.

If it had been published in the late 1970s in the wave of East-meets-West novels that swept into American bookstores after the huge success of Shogun, Children of the Pearl might well have been a bestseller. As it is, the novel is largely forgotten and out of print. At Amazon.com, no one has bothered to post any reader reviews. At Goodreads.com, the book has garnered seven reviews, including this one:

This trilogy is virtually unknown. The books are absolutely amazing. I read the first one, Children of the Pearl, several times while in High School. I then read the following two while in college and loved them just as much. If you like reading about Chinese culture, which I truly do, then this trilogy is a definite must-read!

I can’t comment on the entire trilogy, because I haven’t yet read books two and three. But Children of the Pearl can be read as a stand-alone story, and a very good one at that. It doesn’t set up a cliffhanger to be resolved in another novel. I don’t even know if the sequels deal with the same characters. But it doesn’t matter. The novel is perfect all by itself. It deals with issues that are still very much relevant today: racism, immigration, gender roles, class differences, the mistreatment of workers by wealthy business owners, etc. The novel is at least as well-written as The Joy Luck Club, which is impressive all by itself when you consider that English is not Bezine’s native language.

One of my primary goals for this blog is to bring attention to worthy pieces of American popular fiction that have been neglected or forgotten and to encourage other pop fiction lovers to give them a try. You can buy a used copy of Children of the Pearl online for only a few bucks. The experience of reading it, on the other hand, will be priceless.

Home wrecker! Would not allow my father any contact with his children, my sister Tiki and myself. This woman aided in destroying our family. The truth needs to be revealed.