DR. SEUSS FOR GROWN-UPS

Dr. Seuss was my first literary love. My mother introduced me to him before I could even recite the alphabet. In fact, it was Dr. Seuss who made me want to learn to read, so that I could enjoy his works even when no adult was available to read them to me. Of course, by the time I learned to read, I had many of his works committed to memory.

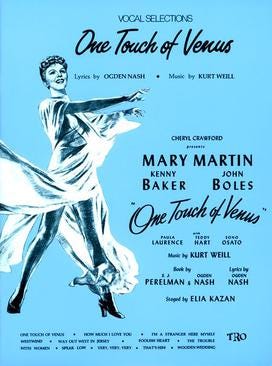

Once, when I was twelve or thirteen, I lamented to my mother that there was no one who wrote like Dr. Seuss but for grown ups. At that point she introduced me to the poetry of Ogden Nash. We didn’t have any Ogden Nash collections in the house, but it didn’t matter. My mother had committed many of the shorter poems to memory (her favorite was “The Lama”). After having been beguiled by my mother’s recitations, I walked down to the nearest library and checked out one of his books. This would have been about 1970 or 1971. At that time, Nash was probably the second most famous living American poet (after Rod McKuen). Once introduced to him, I began finding references to him everywhere: the daily paper, Reader’s Digest, any collection of American humor writing. His work was ubiquitous (the kind of four-dollar word he frequently made fun of although he once employed it as a rhyme for iniquitous). He and Theodor Geisel (aka Dr. Seuss) had a lot in common. They were born less than two years apart, Nash in August of 1902 and Geisel in March of ’04. Both men loved rhyme and meter and wordplay. Geisel wrote almost exclusively for children, but he produced at least a couple of books for adult readers. Most of Nash’s poems were written for sophisticated readers but he also wrote plenty of rhymes for children, including The Tale of Custard The Dragon, which displays a Seuss-like whimsy and in 1995 was made into a standalone book for children and illustrated by Lynn Munsinger (whose illustrations resemble the work of Maurice Sendak more than they do the work of Dr. Seuss). Nash wrote the lyrics for the Broadway musical One Touch of Venus. Seuss’s work provided the inspiration and many of the lyrics for the Broadway musical Seussical.

In the three decades since his death in 1991, Dr. Seuss’s popularity and cultural relevance has continued to grow. Alas, the five decades since Nash’s death, in 1971, have seen his ubiquity fade into near obscurity. That’s why I was thrilled when, last November, The Atlantic ran a feature called Nine Poems for a Tough Winter, which included Nash’s “So Penseroso.” I have spent much of my adult life recommending his work to people. As recently as February 3, I posted an essay about him on my book blog at Substack. I have been hoping for a Nash revival for years. But after what happened to Dr. Seuss earlier this month, when several of his books were discontinued by their publisher for perceived crimes against political correctness, I’m no longer so eager for a Nash revival. Nash, like Geisel, was politically progressive for a man of his era. But any writer born over a century ago is likely to have written a least a few paragraphs that could be used nowadays to portray him as an irredeemable bigot. Nash, alash (as he might have put it), was no exception. If you go looking through his works for a reason to tar him as a racist or a sexist or a clueless cisgender male, you will find what you are looking for:

She would be a perfect wife could she but be restrained by a leash or a fetter,

Because she has the roving tendencies of an Irish setter.

So I hope husbands and wives will continue to debate and combat

over everything debatable and combatable,

Because I believe a little incompatibility is the spice of life,

particularly if he has income and she is pattable.

Nay, flush ye, hush ye, do not fret ye, my little white manchild,

Who, if your parents hadn’t been Caucasian would have been an

ebony or copper or tan child…

I do not know the name of the last chief of the Manhattan Indians, to me he is anonymous,

I suppose he had a name somewhere between the Powhatanish and the Sitting Bullish or the Geronimous

Manhattan, he said, was going to the bowwows,

The average brave and squaw simply couldn’t afford the ridiculous number of scalps demanded for admission to any of the ten top powwows.

But unfortunately there are other afflictions anatomical,

And people insist on thinking that a lot of them are comical…

Suppose, for instance, you have a dreadful attack of jaundice, what do they do?

They come around and smile and say Well well, how are you today,

Dr. Fu-Manchu?

Earlier this month Dr. Seuss Enterprises withdrew the book McElligot’s Pool from circulation, apparently because it contained the word “Eskimo.” Thus, you can imagine what the cancel-culture crowd might think of the Ogden Nash poem “Tell it to the Eskimos – or Tell it to the Esquimaux.” And so, an Ogden Nash revival seems ill-advised at this time. It would only provide fodder for those who seek to signal their own virtue by flogging the dead for their lack of same. Which is a real shame. Because, despite his flaws, Nash was an astute commenter on American culture and human nature, and there is plenty to be learned from his work. For instance, his poem “Seeing Eye to Eye is Believing” perfectly describes the kind of people who hide out in their own ideological bubbles and choose to cling to their beliefs even when the facts contradict them:

When people reject a truth or an untruth it is not because it is a truth or an untruth that they reject it,

No, if it isn’t in accord with their beliefs in the first place they simply say, “Nothing doing,” and refuse to inspect it.

Likewise when they embrace a truth or an untruth it is not for either its truth or its mendacity,

But simply because they have believed it all along and therefore regard the embrace as a tribute to their own fair-mindedness and sagacity.

The poem concludes with this couplet:

Naturally I am not pointing the finger at me,

But I must admit that I find any speaker far more convincing when I agree with him than when I disagree.

The poem illustrates one of Nash’s best traits: he rarely excludes himself from the criticism he directs at the foolishness of mankind.

Another timely poem of Nash’s criticizes America’s colleges and universities for abandoning the teaching of dead white Romans and Greeks in favor of courses more amenable to the job market:

It’s high time to rescue our kids from poetry and prunes and prisms;

Once they start in on ideas and ideals they’ll end up spouting ideologies and isms.

Get them interested in hotel management and phys. Ed, and business administration instead of the so-called finer arts

And you’ll cut off the flow of eggheads and do-gooders and bleeding hearts.

Every campus gets what it deserves and deserves what it gets,

So what do you want on yours – a lot of pinko longhairs, or red-blooded athaletes and drum majorettes?

One of Nash’s poems seems as if it was written specifically to skewer the Twitter mobs that love to turn every minor criticism of woke orthodoxy into a criminal offense:

Our fathers claimed, by obvious madness moved,

Man’s innocent until his guilt is proved.

They would have known, had they not been confused,

He’s innocent until he’s accused.

The university administrators who don’t speak up against the students who shout down invited speakers such Charles Murray might want to consider these lines of Nash’s:

Sometimes with secret pride I sigh,

To think how tolerant am I;

Then wonder which is really mine:

Tolerance, or a rubber spine?

Nash hated euphemisms such as “senior citizen” for “old person.” In a poem called “Laments For a Dying Language III,” he jokes that Hemingway’s famous novel will probably someday have to have its title changed to “The Senior Citizen and the Sea.” He seems to have foreseen a day when a company would be forced to alter the name of a skin-care product called Fair & Lovely because woke critics thought it smacked of white supremacy. What some language police see as progress, Nash saw as the opposite:

My dictionary defines progress as an advance towards perfection.

There has been a lot of progress in my lifetime, but I’m afraid it’s been heading in the wrong direction.

What is the progress that I see?

The headwaiter has progressed to being a maitre-d’.

Near the end of that poem he informs the reader:

Progress might have been all right once, but it went on too long…

There is a lot in Nash’s work that even the social-justice left might like, if they gave him a chance. He is persistently critical of colonialism. In a poem entitled “England Expects,” he writes:

Englishmen are distinguished by their traditions and ceremonials,

And also by their affection for their colonies and their condescension to their colonials.

When foreigners ponder world affairs, why sometimes by doubts they are smitten.

But Englishmen know instinctively that what the world needs most is whatever is best for Great Britain.

At first glance, “The Japanese” would appear to be a problematic poem:

How courteous is the Japanese;

He always says, “Excuse it, please.”

He climbs into his neighbor’s garden,

And smiles, and says, “I beg your pardon”;

He bows and grins a friendly grin,

And calls his hungry family in;

He grins, and bows a friendly bow;

“So sorry, this my garden now.”

But Nash wasn’t talking about race in the poem. Rather he was criticizing the rampant colonization of Asia that the Japanese military undertook in the first four decades of the twentieth century. During that period Japan sent occupying forces into Manchuria, Korea, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, and many other parts of Asia. A young contemporary reader seeing the title of the poem and the Pidgin English employed by Nash might accuse him of political incorrectness (or worse). But nowadays, “colonialism” is one of the evils most reviled by woke social-justice warriors. The fact that Nash was decrying colonialism nearly 90 years ago ought to earn him some respect from the woke crowd. But in an age where people are quick to take offense over the slightest thing, a jokester like Nash, who poked fun of virtually everything he wrote about, isn’t likely to be welcome.

For a man of his time, Nash had fairly enlightened attitudes about race. In one of his poems he dreams hopefully of newspaper headlines that are the opposite of those typical of the era. He wants to see headlines that read “Europe Erupts in Bumper Crops” and “In Georgia, Negro Lynches Mob.” While it’s true that Nash could make fun of American Indians, Asians, and Eskimos, he also pokes fun of the English, the French, the Italians, even the Scottish (No McTavish/Was ever lavish, reads his poem “Genealogical Reflection” in its entirety). He was raised in a time when ethnic humor was fair game. His work is full of jokes based on gender differences and ethnic differences and political differences and socio-economic differences. Almost nothing was sacred to Ogden Nash. I’d love to see his work undergo a resurgence of popularity. But not if it means dragging him through the mud the way that poor Dr. Seuss was recently dragged.