DON'T LISTEN TO DAVID BROOKS: PART II

In my previous entry I examined what was wrong with David Brooks’s recent New York Times column titled “When Novels Mattered.” This entry is an extension of that examination.

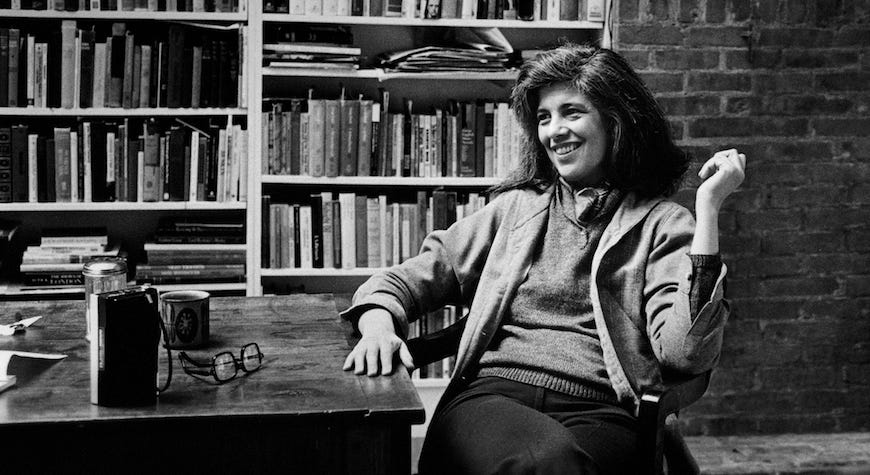

Brooks’s column begins like this: “I’m old enough to remember when novelists were big-time. When I was in college in the 1980s, new novels from Philip Roth, Toni Morrison, Saul Bellow, John Updike, Alice Walker and others were cultural events. There were reviews and counterreviews and arguments about the reviews.” He adds, “Literary talk was so central that even some critics got famous: Susan Sontag, Alfred Kazin and before them Lionel Trilling and Edmund Wilson. There were vastly more book review outlets, in newspapers across the country and in influential magazines like The New Republic.”

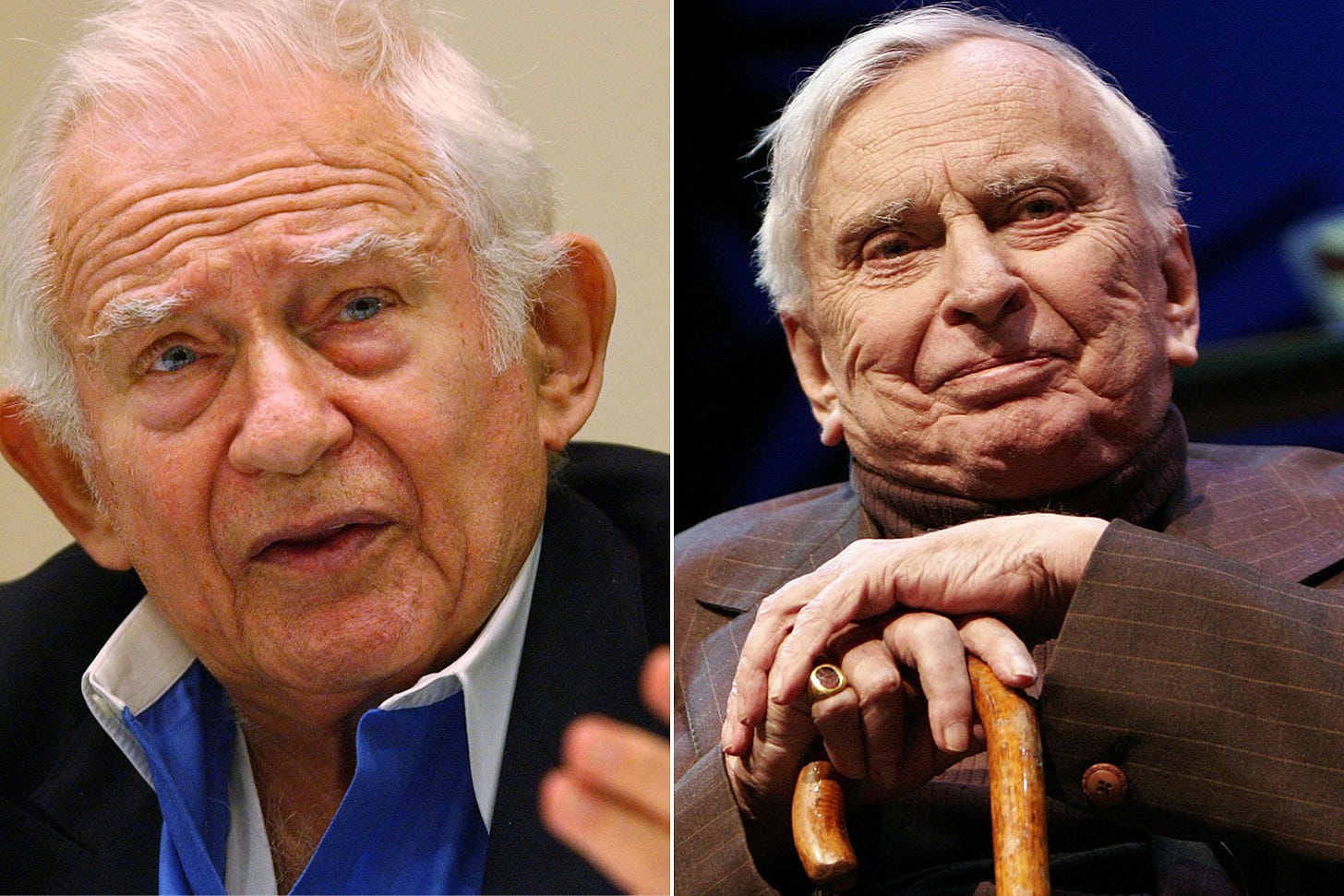

When Brooks envisions book reviews, he sees The New Republic, The Partisan Review, Commentary, and a handful of other old-media, dead-tree venues that, back in the day, were popular from Greenwich Village all the way to Gramercy Park, the kind of magazines that were read by east-coast academic elites and almost no one else. The critics Brooks mentions above were associated with Columbia University (Kazin and Trilling), Harvard, Berkeley, and the University of Chicago (Sontag), and Princeton (Wilson). Brooks’s father taught at NYU; his mother was educated at Columbia; and Brooks himself graduated from the University of Chicago. I believe that what he truly misses is not a time when novels mattered, but a time when east coast academic elites like himself were the only ones allowed to comment on which novels mattered and why. When Brooks reaches for the names of novelists who mattered back in the day, he inevitably comes up mostly with east coast elites like Gore Vidal (a native New Yorker and a child of privilege whose grandfather was a U.S. Senator), Norman Mailer (a lifelong New York resident and Harvard grad), John Updike (born in Pennsylvania, long affiliated with The New Yorker, and a graduate of Harvard).

It is true that, back in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, Vidal, Mailer and Updike generated a lot of ink in places like The New York Review of Books, The Paris Review, and the New York Times Book Review. They generated ink not because they were especially brilliant but because they were literary gadflies who performed well on TV and who attended all the right schools and/or literary parties. Mailer and Vidal also occasionally ran losing campaigns for public office, which also gained them notoriety. What these men didn’t do was write a lot of groundbreaking novels. Between them, they managed to write some of the worst novels of their generation, books like Myron, Two Sisters, and Dark Green, Bright Red (Vidal); Barbary Shore, The Deer Park, and The American Dream (Mailer); and Toward the End of Time, Seek My Face, and The Widows of Eastwick (Updike). To be fair, they wrote some pretty decent novels as well, such as Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, Vidal’s Lincoln, and Updike’s Rabbit, Run. But the attention paid to them by the kinds of old-school book reviews whose passing Brooks laments far surpassed what their literary talents merited.

Back in the 1960s, almost none of the serious literary reviews paid any attention at all to the works of writers like Philip K. Dick, Elmore Leonard, or Patricia Highsmith. But now, sixty years later, it seems clear that those were some of the most innovative and important American writers of the twentieth century, and their influence on contemporary American culture is far more profound than the influence of Updike, Vidal, or Mailer. The current (July 7-14) issue of The New Yorker contains a six-page retrospective, written by Anthony Lane, on the life and career of Elmore Leonard. Lane doesn’t hesitate to call Leonard a “great writer,” although, certainly, had Lionel Trilling or “Bunny” Wilson (who loathed detective fiction – see, for instance, “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?”) ever deigned to read a novel by Elmore Leonard, they’d have immediately dismissed it as popular garbage. But here is Anthony Lane: “Has anyone listened more intently than Leonard to the infinite bandwidths of spoken English? So sharp are his ears, when pricked up, that somebody, way back in the Leonard genealogy must have made out with a lynx. That is why he earns his slot in the Library of America: he turns the page and starts a fresh chapter in the chronicle of American prose. His genius is twofold; he is unrivalled not only as a listener but as a nerveless transcriber of what he hears. No stenographer in a court of law could be more accurate. His people open their mouths, and we know at once, within a paragraph, or even a clause, who dreamed them up. Many folks, in many novels, might remark, ‘You certainly have a long winter.’ But only someone in a Leonard novel would reply, ‘Or you could look at it as kind of an asshole spring.’”

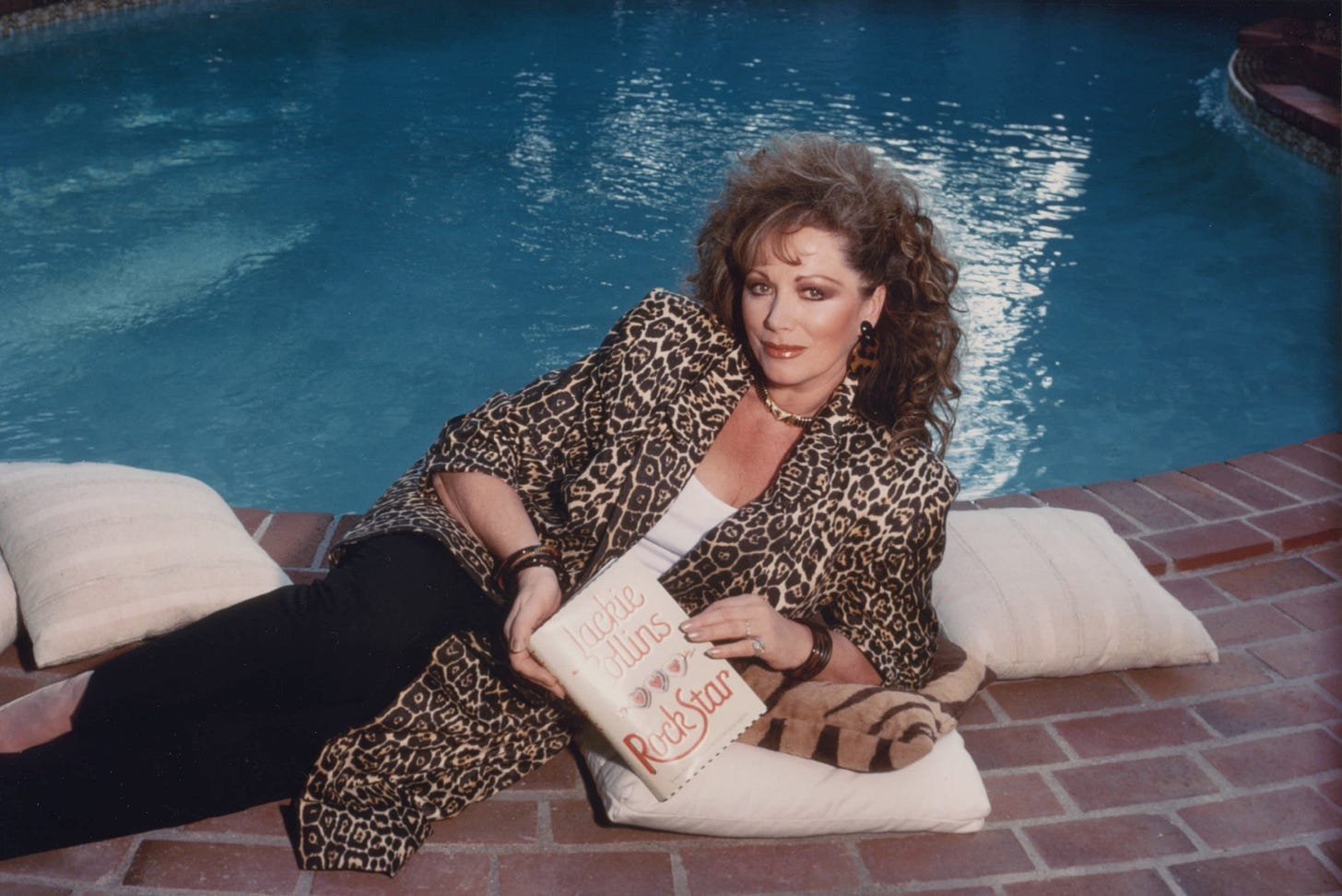

If the critics whose passing Brooks laments had won the day, readers nowadays would still be having the fiction of Vidal, Mailer, and Updike pushed upon them in the pages of The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and The New York Review of Books. Back in the era that ran from the 1960s through the 1980s, the only magazines championing the likes of Leonard, Highsmith and Jim Thompson were pulps such as Ellery Queens Mystery Magazine, Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, and Mike Shayne’s Mystery Magazine. Fortunately, the common readers of America had the good sense to largely ignore the likes of Trilling, Wilson, and Kazin, and focus instead on the spinner racks of America’s supermarkets, airport gift shops, and Waldenbooks chain stores, which is where all the good stuff – romance novels, mysteries, fantasy novels, sci-fi, and action thrillers – tended to conglomerate. Nowadays, the highbrow magazines have finally started to catch on to what pop fiction lovers have known for decades: the best of American fiction can usually be found in the genre aisles. Not only did The New Yorker just run a long appreciation of Elmore Leonard in its pages, The Atlantic, back in May, featured an essay titled, “We’re All Living In A Carl Hiaasen Novel,” which acknowledged what pop-fiction fans have known for years: Nobody writes better about the absurdities of contemporary America than crime writer Carl Hiaasen. My wife and I first became fans of his when we read Tourist Season back in 1986. If we had waited around to see if his work would be praised by some mainstream tastemaker in the pages of The New Yorker or The Atlantic, we’d have missed out on the thrill of discovering a new writer just as he was first breaking into print. I first read Elmore Leonard after seeing the movie Mr. Majestyk back in 1974. I went out the next day and purchased Leonard’s novelization of the film. If I had waited around for a mainstream review of the novel Mr. Majestyk before buying it, I’d still be waiting. Not only was it a piece of pulp, it was also a film novelization, probably the least reputable genre of popular fiction known to mankind, and certainly not something that ever got written about in the pages of The Partisan Review or The New Republic. Likewise, back in 2021, the Atlantic’s Sophie Gilbert ran an appreciation of the fiction of Jackie Collins, famous for her “bonkbusters.” No reputable book review would have written favorably about Collins or her books in the era that David Brooks longs for.

In his lament, David Brooks notes that, ”There were vastly more book review outlets” back when he was in college in the 1980s. This is true if you count only old-school mainstream newspapers and magazines as book review outlets. Otherwise, Brooks’s claim is nonsense. The outlet you are reading right now – A Boomer and His Books – is one of hundreds of thousands of online sites in America dedicated to reviewing books. Even in his column, Brooks links to an Owen Yingling essay published at…Substack. Nowadays, there are not only more journalistic venues than ever dedicated to commentary about books, they cover a much broader swath of the literary market than ever before. Today you can find dozens (if not hundreds) of online book sites dedicated only to romantasy, a genre that wasn’t recognized by any mainstream review outlets in the era that Brooks considers a Golden Age of book reviewing. Likewise you can find numerous sites dedicated only to so-called “dark academia” fiction (think Donna Tartt’s The Secret History). My blog frequently acts as a champion of older writers and books that have been unjustly forgotten over time. But that is a niche covered by dozens of other blogs as well. Type into a search engine a phrase like “neglected books” and you’ll finds links to plenty of sites dedicated to forgotten books and authors. My late friend Don Napoli maintained a blog (still accessible but no longer active) called Reading California Fiction that celebrated novels that were set in California and published between 1900 and 1960. Most of the books he wrote about would never have been reviewed in the pages of the kinds of mainstream book reviews of mid-century America whose loss of influence makes David Brooks so sad.

Brooks is not nostalgic for an era when novels mattered but for an era when a small handful of novels and novelists mattered and their numbers were curated by an elite cadre of mostly east coast gatekeepers with Ivy League academic credentials – in other words, people like David Brooks. The literary scene is much more democratic now than it ever was. Writers such as Colleen Hoover, E. L. James, and Andy Weir probably never would have been published back in the day when east-coast elites ruled the publishing world. Those writers started out by writing so-called “fan fiction,” stories and novels that they self-published because no traditional publishing house was interested in the work. You can argue that the work of these writers is lousy, but no one can argue that there isn’t a great demand for it. Their novels matter to millions of Americans, a fact that probably riles literary snobs.

You can argue that TV and film are more powerful cultural forces nowadays than prose fiction, but that was true even back in the 1980s, and probably in the 1950s, as well. But many of the most prestigious and/or talked-about film and TV properties of the last few decades – Game of Thrones, Big Little Lies, The Queen’s Gambit, The Handmaid’s Tale, Dune, Minority Report, Presumed Innocent, Ready Player One, Outlander, Ripley, Bosch, Justified, It, etc. – are based upon works of popular fiction. That’s just another example of how much novels matter nowadays.

Cultural elitists like Brooks long for the day when they had greater control over the American literary conversation. But that day is long gone. It is ironic that Brooks sees the 1980s as a sort of Golden Era for serious fiction, because it was in the 1980s that so-called serious literary writers began to see that, by ignoring popular genres, they were rendering themselves largely irrelevant to the vast majority of American readers. As Tom Wolfe noted in his influential 1989 essay “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast,” at some point in the mid-20th century, serious American literary novelists stopped paying much attention to life as it is actually lived by most ordinary Americans (whom he dubbed the “billion-footed beast”) and began playing postmodern games in the manner of John Barth’s Chimera and Ronald Sukenick’s Up. Wolfe quoted John Hawkes, another postmodernist, who once wrote that, “I began to write fiction on the assumption that the true enemies of the novel were plot, character, setting, and theme.” Wolfe disliked this trend. He believed highbrow literary types had ceded the field of realistic fiction to writers of more commercial fiction. In his essay, he wrote:

In many years, the most highly praised books of fiction have been overshadowed in literary terms by writers whom literary people customarily dismiss as “writers of popular fiction” (a curious epithet) or as genre novelists. I am thinking of novelists such as John le Carré and Joseph Wambaugh. Leaving the question of talent aside, le Carré and Wambaugh have one enormous advantage over their more literary confreres. They are not only willing to wrestle the beast; they actually love the battle.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, critics and highbrow academics lavished praise on the books of (white male) authors such as Barth and Larry Woiwode. Woiwode won the William Faulkner Foundation Award, a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, two prizes from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the John Dos Passos Prize for Literature, the Aga Kahn Prize for Fiction, and was a finalist for a National Book Award. Fourteen chapters of his 1975 novel, Beyond the Bedroom Wall, were published in The New Yorker. Barth was twice nominated for National Book Awards and won the F. Scott Fitzgerald Award for Outstanding Achievement in American Ficiton, the PEN/Malamud Award, and grants from The Rockefeller Foundation and the National Institute of Arts and Letters. Their books were fetishized on elite university campuses and in the pages of highbrow literary reviews, but nowhere else in America. When they died recently (Woiwode in 2022, Barth in 2024), their passing garnered almost no attention at all in the press. They were so thoroughly forgotten by then that even highbrow publications barely paid any attention to their deaths. Why did this happen? Because their entire careers were made possible only because they were writing for fellow members of their tiny, elite literary clerisy. They never had to worry about pleasing large numbers of readers.

But that type of elite literary bubble began to burst in the 1980s, by which time mainstream American publishers had grown tired of bringing out highbrow novels that were guaranteed to lose money by selling no more than twelve hundred copies, all of them purchased by academic libraries and Ivy League literary professors. As chronicled by Dan Sinykin in Big Fiction, his 2023 account of how conglomerate publishing changed American literature, this bubble-bursting began when highbrow writers like Toni Morrison, Cormac McCarthy and others saw that, if they wanted to reach a larger readership and attain any sort of widespread cultural relevance, they were going to have to embrace a lot of the qualities that made American popular fiction – as exemplified by Jaws, The Exorcist, Shogun, Rosemary’s Baby, The Shining – the world’s best-loved genre of literature. As Sinykin notes, “The shifting terrain made it more attractive, or less inhibiting, for literary writers to adopt genre techniques, as Morrison did in Beloved [essentially a ghost story]. Umberto Eco had early success in this mode with The Name of the Rose (1980) [a historical mystery]. Denis Johnson’s spy novel, The Stars at Noon, came out in 1984. Paul Auster published his New York Trilogy [three metaphysical mystery tales] the same year as Beloved. A.S. Byatt published Possession, a literary romance novel, in 1990. The literati began to rethink its snobbery – the weakened position of the mass market and the use of genre by Auster, Byatt, Eco, Johnson, and Morrison made such snobbery unnecessary, outdated.”

Sinykin notes that “Random House fired a president who defended boutique novelists and hired one who demanded each book support itself. [As a result, Cormac] McCarthy’s style changed. He adopted genre techniques that would persist in his work.”

In other words, highbrow critics such as Trilling, Kazin, Wilson Sontag, et al., were leading the American novel not into a realm where it would matter more and more, but down a road that would take it to complete irrelevance. The highbrow critics championed a type of American novel that only they could appreciate (often because it was complete nonsense, or filled with references to such obscure works of art that no one but an Ivy League Ph.D. could possibly follow it). Had they been allowed to get away with it, the serious American novel would matter a lot less today than it did in what Brooks perceives as a Golden Era. Instead, the ordinary American reader came along to save the day. The so-called serious novel became more relevant only when it embraced devices and formulas that had always appealed to pop fiction fans. Thus, we now have egghead writers like Colson Whitehead penning zombie novels (Zone One), John Banville writing Philip Marlowe novels (The Black-Eyed Blonde, under the pseudonym Benjamin Black), and Emily St. John Mandel writing post-apocalyptic tales (Station Eleven). Even Norman Mailer and Joan Didion, towards the end of their novel-writing careers, turned to the espionage genre, in books like The Last the He Wanted, Harlot’s Ghost, and The Castle in the Forest. Still, if you want a good ghost story, you’d probably be better off seeking one written by Stephen King or Peter Straub than by Toni Morrison. If you want a good detective story, you’re better off seeking out the work of Michael Connelly or Sue Grafton than the work of Benjamin Black. If you want a good spy novel, seek out the work of Alex Berenson or Brad Thor rather than a novel by Didion or Mailer.

If you want to know what the American novel would look like these days if David Brooks’s favorite critics had been allowed to continue deciding what books mattered and what books didn’t, just take a look at contemporary American poetry. There was a time when American poets produced work that appealed both to academic snobs and ordinary readers. In the first half of the twentieth century, plenty of ordinary American readers were able to recite lines written by Robert Frost and Emily Dickinson and Edgar Allen Poe and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and any number of other popular poets. Newspapers and magazines back then often paid decent money for poetry, which made writing it a desirable prospect not just for academics seeking to pad their resumes but also for nonacademic writers who were merely looking to make a living. What’s more, humorous poetry books by the likes of Ogden Nash and Dorothy Parker and Phyllis McGinley and Willard R. Espy often sold tens of thousands of copies, mostly to ordinary (i.e., non-elite-educated) American readers. Currently, the most highly regarded American poet is probably Jorie Graham, who has twice won the Pulitzer Prize and has garnered numerous other awards, as well. I doubt if one American in a million can name the title of a Jorie Graham poetry collection. Hell, I doubt if one American in a million can name the title of a single poem by Graham, or quote from it the way that plenty of Americans can still recite from Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” or “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening.” Graham, like pretty much every other poet ensconced in an American academic institution, doesn’t need to write poetry that appeals to a wide readership. She is writing poetry only for the types of highbrow critics whose influence on the American novel has, thankfully, waned over the past forty years. Here’s a sample of her work, from a poem called “Just Before”:

At some point in the day, as such, there was a pool. Of stillness. One bent to brush one's hair, and, lifting again, there it was, the opening—one glanced away from a mirror, and there, before one's glance reached the street, it was, dilation and breath—a name called out in another's yard—a breeze from where—the log collapsing inward of a sudden into its hearth—it burning further, feathery—you hear it but you don't look up—yet there it bloomed—an un- learning—all byway no birthpain—dew—sand falling onto sand—a threat from which you shall have no reprieve—then the reprieve—Some felt it was freedom, or a split-second of unearthliness—but no, it was far from un-

I copied that from the poets.org website, but Graham’s wonky layout gets lost when one of her pieces is pasted into a word document. Trust me, however, that the original layout doesn’t make the poem any more poetic or coherent. And if the bygone gatekeepers of American fiction – men like Wilson, Kazin, and Trilling – had had their way, contemporary American novels would read a lot like Jorie Graham’s dog’s breakfast of a poem.

Novels still matter a great deal in America. What angers men like Brooks, is that east coast elites like themselves are no longer in charge of determining which novels and novelists matter most. Brooks is a longtime champion of capitalism, so it shouldn’t surprise him that capitalism, as embodied by the contemporary American publishing conglomerate, now has a lot to say about which novels matter most in America. But smart capitalists are also highly responsive to the demands of the consumer. And American book-buyers nowadays have a powerful voice in the discussion of which novels matter most. When capitalism fails those consumers, they’ll go outside the usual marketplace in order to find books by the likes of Andy Weir and Colleen Hoover, books that the conglomerates have no interest in. But, eventually, even the Weirs and Hoovers of the world get Hoovered up by the capitalist conglomerates. And that is why, for all its imperfections, the American novel is probably better off now than it was when its fate lay in the hands of a few east-coast intellectual snobs.