ALL THINGS MUST PASS: RICHARD MATHESON, GEORGE R. STEWART AND THE BIRTH OF THE CALI-POCALYPSE

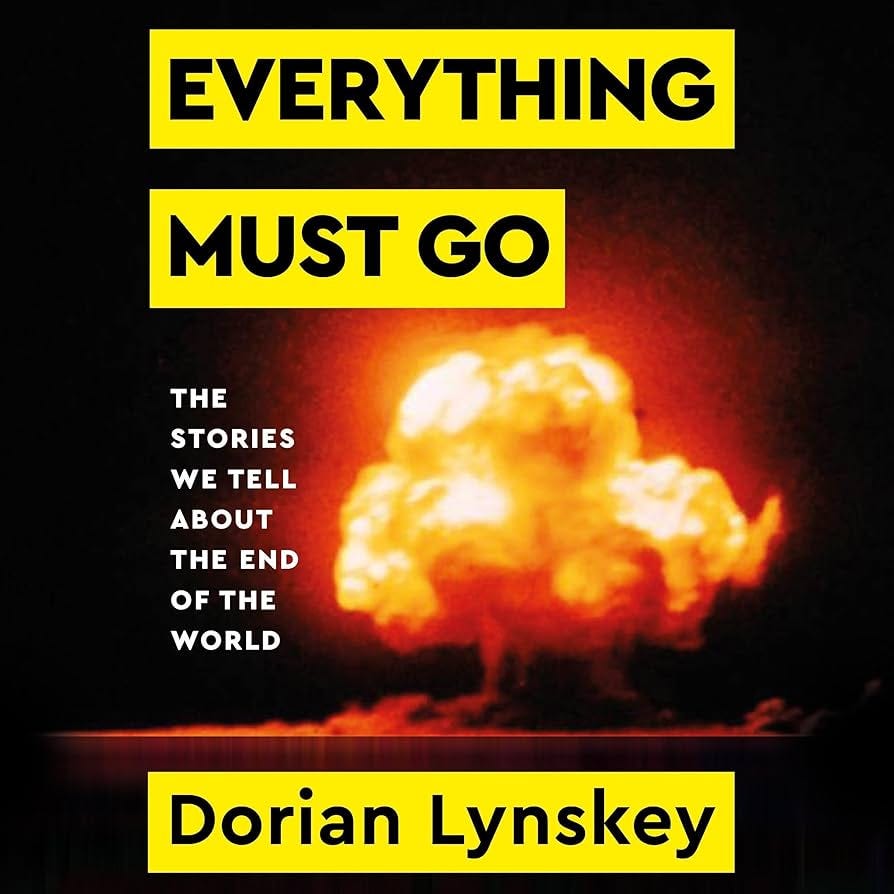

The end of the world is back in vogue. Numerous publications have recently featured articles about the possibility that World War III and the end of the world might be at hand. Speculation about the end of mankind goes at least as far back as the Biblical book of Genesis and the story of Noah and the ark. Mary Shelley, famous for her 1818 novel Frankenstein, rekindled interest in end-of-mankind narratives with her second novel, The Last Man. Published in 1826, The Last Man is the story of a pandemic that kills almost every human being on earth. Though the novel wasn’t immediately successful, it later became the inspiration for much of what we now call apocalyptic fiction, a genre that became enormously popular after the advent of the atomic bomb. British journalist Dorian Lynskey’s recent book, Everything Must Go: The Stories We Tell About the End of the World, recounts not only the birth of Shelley’s The Last Man but also many of its offspring, books such as Fail-Safe and On The Beach and The Andromeda Strain, as well as films such as Dr. Strangelove and Night of the Living Dead and Outbreak.

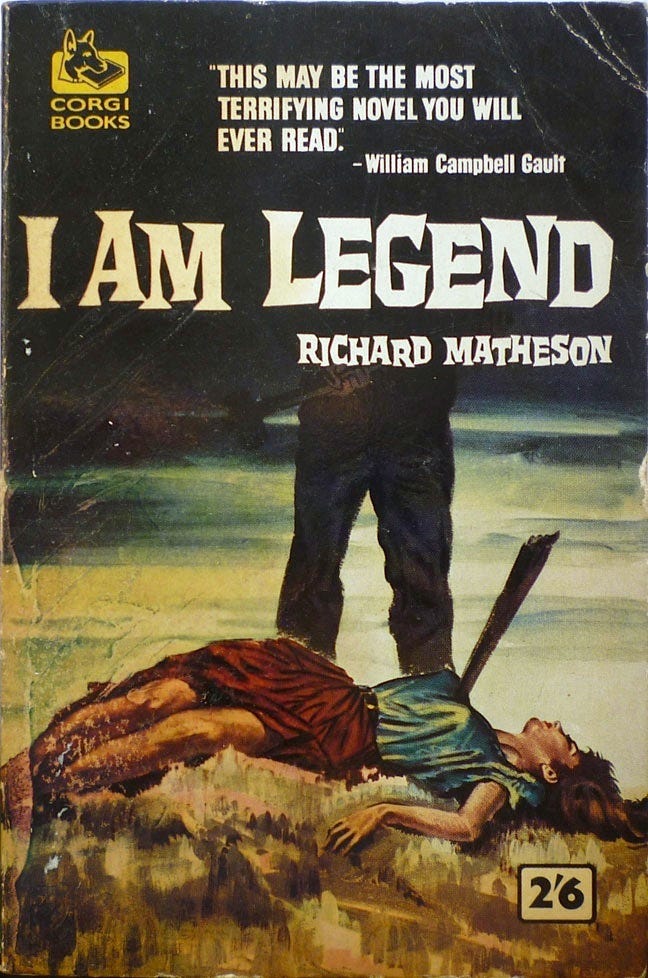

Two of the most influential American novels of the apocalypse are celebrating significant birthdays this year. George R. Stewart’s Earth Abides, first published on October 24, 1949, turns 75 today. And Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, first published on August 7, 1954, turned 70 a few months back. The books have a lot of similarities. Each book’s title also serves as its final words. Stewart’s title comes from Ecclesiastes: “Men come and go, but earth abides.” Matheson’s title seems to be a punning allusion to an incident recounted in the Gospel of Mark, wherein Jesus meets a man possessed by a demon. Jesus asks the demon for his name. The demon responds, “My name is Legion, for we are many.”

It’s probably not a coincidence that many of the best American apocalypse stories come out of California. Goodreads has a list of 76 Cali-pocalypse tales and it is far from complete.

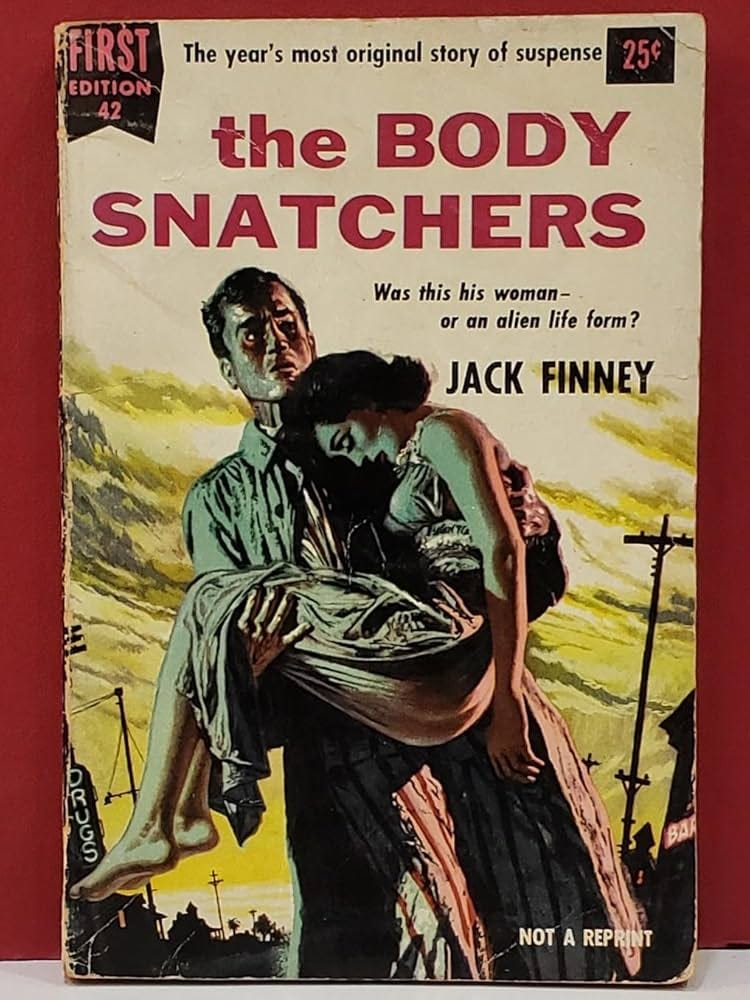

Most Cali-pocalypse tales take place either in the San Francisco Bay Area or the Los Angeles area. Few writers ever bother to destroy San Diego, Bakersfield, or Sacramento. Bay Area apocalypse tales include Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers, Philip K. Dick’s Dr. Bloodmoney, and Stewart’s Earth Abides. L.A.-area apocalypse tales include Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Wild Shore, Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower, and Matheson’s I Am Legend. With its reputation for earthquakes and wildfires and Pacific storms, the Golden State is an ideal location for all sorts of disaster stories. The state also hosts more than thirty military bases, a number of major defense contractors, and numerous research facilities, including the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, where a great deal of nuclear-weapons research took place after WWII. Add to that the fact that the state annually draws a huge number of foreign tourists, making it a likely spot for an overseas virus to reach America, and California would seem to be the perfect staging ground for just about any kind of apocalypse. New York City, whose residents live mostly in multi-family housing, can’t offer the kind of eerie, unpopulated suburban landscapes that California can. Without any traffic, you could drive from one end of Manhattan to the other in a few minutes. But both Stewart’s Earth Abides and Matheson’s I Am Legend linger over their endless rolling hills and suburban streets, whose ranch-style houses have been rendered largely empty by mysterious pandemics.

Nowadays, Matheson’s story is probably the best known of the two, primarily because of the several films that it has inspired: 1964’s The Last Man on Earth (starring Vincent Price and with a title that directly references Shelley’s influence), 1971’s The Omega Man (starring Charleton Heston and with a title that indirectly references Shelley’s influence), and 2007’s I Am Legend (starring Will Smith). George A. Romero’s 1968 film, Night of the Living Dead, is also believed to have been inspired by Matheson’s novel, though he isn’t credited for it in any way.

In Everything Must Go, Dorian Lynskey writes, “The book that really made the last man a going concern in popular fiction was Richard Matheson’s hugely influential 1954 novel I Am Legend.” Matheson’s brilliant idea was to merge the plot of Shelley’s The Last Man with the zombie novel, which wasn’t even really a thing back in 1954. Zombies originated from Haitian folklore, but they didn’t become a mainstay of popular fiction in English until fairly recently. When Matheson inserted them into I Am Legend, even he didn’t have a name for them, so his monsters are called vampires, despite lacking many of the qualities we now regard as quintessentially vampiric: eloquence, suavity, beauty (Tom Cruise, Brad Pitt, Kirsten Dunst, Kristen Stewart, Dakota Fanning, and Robert Pattinson are just a few of the actors who have played comely vampires in recent decades). Matheson’s creatures – call them zambies, if you will – crouch on their haunches, grind their teeth back and forth, move very slowly, and do more howling than speaking. Wikipedia notes that, “A new version of the zombie, distinct from that described in Haitian folklore, emerged in popular culture during the latter half of the 20th century. This interpretation of the zombie, as an undead person that attacks and eats the flesh of living people, is drawn largely from George A. Romero’s film Night of the Living Dead (1968), which was partly inspired by Richard Matheson’s novel I Am Legend.” Philip K. Dick’s 1956 novel, The World Jones Made, also appears to be at least partially inspired by I Am Legend. It was published just two years afterwards and the apocalypse it describes begins in 1977, one year after Matheson’s. Both apocalypses were triggered by war and both produced mindless hordes of zombie-like creatures, although Dick’s are not deadly.

It’s not quite accurate to say that Matheson invented the modern Last Man on Earth novel as well as the zombie novel, but he probably deserves more credit for the twentieth- and twenty-first-century popularity of those genres than any other person. And though I Am Legend isn’t quite a vampire novel, Matheson’s decision to bring the word “vampire” out of the shadowy world of the past and insert it into a post-WWII apocalypse tale also proved to be highly influential. Nearly twenty years later, Matheson would transform an unpublished novel by Jeff Rice called The Kolchak Papers into a screenplay called The Night Stalker, a vampire tale which became the most-watched TV movie ever when it was first broadcast on January 11, 1972. The TV soap opera Dark Shadows (1966-71), which featured a vampire in a major role, preceded The Night Stalker but, though set in the 1960s, its story centered upon a small fictional New England town that felt decidedly nineteenth-century. Matheson’s Night Stalker was set in busy, neon-lit Las Vegas and felt decidedly contemporary. It terrified people precisely because it was set in modern times. Most viewers were used to thinking of vampires as monsters out of the Victorian past, confined mainly to Romania and elsewhere in Eastern Europe. Matheson upended all of those quaint notions. And he unleashed a flood of contemporary vampires. Curiously, the author who benefitted most from Matheson’s work wasn’t Jeff Rice but a woman who called herself Anne Rice (her birth name was Howard O’Brian). Her first book, Interview With the Vampire, was published in 1976. Matheson’s I Am Legend begins in January of 1976 and takes place mostly in that year. He seems to have intuited that vampires would be hot that year.

Back in 1954, however, the monsters Matheson called vampires were not the suave dandies that Anne Rice would later write about. Like zombies, the vampires of I Am Legend have no real identity. They usually attack fairly slowly and operate as though they are controlled by a single hive mind. They have some vocal abilities, but they mostly just terrorize the protagonist with cries of, “Come out, Neville!” Like vampires, they come out only at night, feast on human blood, and can be killed with a wooden stake driven through their hearts. They are also repelled by garlic and crosses. But, unlike traditional vampires, Matheson’s can see themselves in mirrors and they have no connection to bats. When they can’t find a human to feast upon (and Neville is the only human in the novel) they resort to feasting on one of their own, usually a weaker female member of the pack. “They did that often,” Matheson writes. “There was no union among them. Their need was their only motivation.” In Matheson’s world, dogs can also become vampires.

Matheson’s novel takes place in Los Angeles shortly after a world war has wiped out most of earth’s population and unleashed a pandemic that has turned every survivor but Neville into a sort of walking corpse (Neville hopes there are others, but he never encounters any). Neville lives in a house on Cimarron Street in LA. He keeps the doors and windows boarded up whenever he is home. He still has a working refrigerator and some other appliances thanks to a generator he keeps in the garage. He is an example of the “competent man” trope, popularized in the 1950s by Robert A. Heinlein. In pop fiction, a competent man is a stock character who possesses a range of skills that few real-life individuals do. (This trope later gave birth to the competent young woman trope known as a “Mary Sue.”)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Sue

Neville demonstrates skill in carpentry, automotive repair, small appliance repair, biology, vampire killing, and so forth. He leaves the house only by day, mostly just to collect supplies from ransacked hardware stores and grocery stores. While he is out, he also kills any sleeping vampires he happens to run across, and he runs across quite a few of them. At night, the vampires return the favor by slouching towards Cimarron to try to kill Neville.

Neville’s wife died of the same malady that killed all the other people on earth. He buried her but, in a twist straight out of W.W. Jacobs’s classic 1902 short story The Monkey’s Paw, she returned later that night, having risen from the dead, sort of. This time around, he had to drive a stake through her heart before reburying her. Stephen King has often said that Matheson influenced his work more than any other writer, and echoes of I Am Legend can be found in a lot of his works, including The Stand and Pet Semetary. King’s fondness for bleak, if not downright apocalyptic, endings might have something to do with Matheson’s influence as well. In a chapter dedicated to Last Man stories, Dorian Lynskey writes, “With the notable exceptions of Mary Shelley and Richard Matheson, almost every last-man story retreats from the premise sooner or later. It seems that we find it easy to imagine the end of the world but not going through it alone.”

Matheson was a young married man with children when he wrote I Am Legend. His early years as a writer were bad times for him. He once told an interviewer, “My theme in those years was of a man, isolated and alone, and assaulted on all sides by everything you could imagine.” I Am Legend was published in the same year as Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers, another Cali-pocalypse tale and the source of the 1956 film Invasion of the Body Snatchers and several others. Both are about human beings being turned into soulless empty vessels. Some early commentators thought the pod people (in Body Snatchers) and zombies (I Am Legend) were meant to represent the sneaking threat of communism or socialism or atheism. Others interpreted the empty men as representing the dehumanizing conformity of the American suburban dweller. Both books, like almost all worthwhile art, are open to a variety of interpretations. A recent academic study of I Am Legend published in Advances in Literary Study, sees it as an attack upon wokeness and “as a metaphor for the sociopolitical collapse of patriarchal hegemony.” Those academics sure know how to suck the fun out of pop culture.

Considering how influential it became, it is surprising to learn that I Am Legend wasn’t a critical success at the time of its publication. But this had also been the fate of Mary Shelley’s The Last Man. An early critic of Shelley’s novel wrote in The Monthly Review, “Every writer who has hitherto ventured on the theme, has fallen infinitely beneath it. Mrs. Shelley, in following their example, has merely made herself ridiculous…The whole appears to be the offspring of a diseased imagination, and of a most polluted taste.” Damon Knight, a prominent sci-fi writer and critic and editor, wrote of I Am Legend, “The book is full of good ideas, every other one of which is immediately dropped and kicked out of sight. The characters are child’s drawings, as blank-eyed and expressionless as the author himself in his back-cover photograph. The plot limps. All the same, the story could have been an admirable minor work in the tradition of Dracula, if only the author, or somebody, had not insisted on encumbering it with the year’s most childish set of ‘scientific’ rationalizations.” In the sci-fi magazine Galaxy, another critic noted that the book was, “a weird [and] rather slow-moving first novel…a horrid, violent, sometimes exciting but too often overdone tour de force.” (I Am Legend was Matheson’s third published novel, not his first).

Some of what these naysayers wrote is true, although largely beside the point. I Am Legend is not an elegant or shapely novel. Matheson wasn’t a great prose stylist. His favorite verb is “jerk” and he overuses it, sometimes in unintentionally humorous ways (“He actually found himself jerking off the crossbar from the door.” “Abruptly he jerked up his right fist…” “He jerked the car to the curb…” “His body jerked back…” “Throwing the catch and jerking down the rear gate…”). The book is filled with intentionally creepy passages, but sometimes, because of Matheson’s clumsy phrasing, even ordinary actions unintentionally conjure creepy images: “His eyes rushed over the lawn.” Try getting that image out of your head. His short, choppy sentences are the opposite of Mary Shelley’s in The Last Man, which are often overly ornate:

“Thus I stood upon a pinnacle, a sea of evil rolled at my feet; I was about to precipitate myself into it, and rush like a torrent over all obstructions to the object of my wishes – when a stranger influence came over the current of my fortunes, and changed their boisterous course to what was in comparison like the gentle meanderings of a meadow-encircling streamlet.”

I think this means, “I considered suicide but abandoned the idea.” Her sentences often resemble monsters stitched together from a variety of human corpses. I prefer Matheson’s bad prose to Shelley’s because the meanings of his sentences are generally clear. Unlike Shelley, however, Matheson doesn’t seem to have aspired to write long, eloquent novels exploring every aspect of, say, existential loneliness. He was an ideas man, an absolute wizard at coming up with clever little fictional conceits. Little to nothing is known about the drivers of the car and the semi-truck in Duel, the Stephen Spielberg film (his first) that was produced from a script by Matheson (based on his own story, which had been published in Playboy). That lack of knowledge gives the film (and the short story) power, makes it scarier. Dennis Weaver’s everyman hasn’t done anything wrong, but for some reason the unseen driver of a monstrous truck is trying to kill him. As in Duel, part of what gives the novel I Am Legend its power is the fact that Matheson elides so much of the information we need to fully understand the world he has created. When a serious literary author does this, he often earns plaudits. At the end of Chapter V of Joseph Conrad’s Typhoon, for instance, as a steam ship approaches a raging hurricane at sea, the author writes: “Captain MacWhirr was moved to declare, in a tone of vexation, as it were: ‘I wouldn’t like to lose her [his ship].’” The next sentence reads simply: “He was spared that annoyance,” without telling us how this was accomplished. This is often heralded as one of the greatest elisions in English literature, right up there with Shakespeare’s “Exit, pursued by a bear.” But when a popular novelist tries something like that, he’s usually accused of being forgetful or lazy. But Matheson wasn’t being lazy or forgetful when he elided information about his post-apocalyptic landscape. He was simply forcing his readers to use their own imaginations to explain exactly how the world fell into such a sorry state and why Robert Neville finds himself the last human being on earth. Matheson was more interested in the cat-and-mouse game between Neville and his chief tormentor Ben Cortman (the vampire/zombie who is always calling, “Come out, Neville!”). Cortman was once Neville’s neighbor. The two men carpooled to work together. Something horrible has come between them, but Matheson wants you to figure out exactly what it is. I Am Legend is a short novel. My vintage paperback edition runs to 174 pages (Charleton Heston read the whole thing during an airplane flight, which convinced him it would be a good movie; he was apparently unaware that it had already been filmed at least once). The prominent vampire novels that came after it – works such as King’s ‘Salem’s Lot, Rice’s Queen of the Damned, George R.R. Martin’s Fevre Dream, and Justin Cronin’s The Passage trilogy – tended to be much longer and more fully realized. But in 2012 The Horror Writers Association selected I Am Legend as the greatest vampire novel of the 20th century. It was a strange honor to bestow upon a book whose monsters more closely resemble zombies, but Matheson specialized in weird fiction. It makes sense that he would win weird accolades. Whether you regard it as a zombie novel, a vampire novel, a Cali-pocalypse novel, or just a very good thriller, I Am Legend is, like Robert Neville for much of the book, a survivor. It has been through more American editions than I can count. For years, most reprints of the novel have been appropriately pulpy and cheap. My paperback movie tie-in edition features the film title The Omega Man more prominently than the original title. But in 2018 the Folio Society gave Matheson’s book the high-class treatment that a bona fide classic deserves. The slip-cased Folio edition features an introduction by Joe Hill (Stephen King’s son) and illustrations by Dave McKean.

Dorian Lynskey doesn’t care much for either the 1964 film adaptation, The Last Man on Earth, or 1971’s The Omega Man. He calls the former “glum and inert” and the latter “tonally chaotic.” Stephen King, in his book Danse Macabre, dissed The Omega Man (“[T]he vampires become almost cartoon Gestapo agents in their black clothes and their sunglasses.”) but praised The Last Man on Earth: “This film is more faithful to Matheson’s novel, and as a result it offers a subtext which tells us that politics themselves are not immutable, that times change, and that Neville’s very success as a vampire-hunter…has turned him into the monster, the outlaw, the Gestapo agent who strikes at the helpless as they sleep.” King called it “the ultimate political horror film” and believed it had something to say to a country shocked by the likes of the My Lai Massacre and the Kent State shootings, both of which occurred years after the film was made. King was writing in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when memories of Watergate were still strong in America. At that time, nearly everything was being viewed through a political lens by pundits and commentators, even pop cultural products that were never meant to carry any political weight at all. Thus, I think he credited The Last Man on Earth with more political savvy than it actually possesses. Nonetheless, I think the film is a good one. I’m also fond of The Omega Man.

Neil Gaiman has observed of Matheson, “He was a giant, and you know his stories, even if you think you don’t.” Matheson’s best work tends to be short and pared down to the basics, which is why it worked so well in a TV anthology format such as The Twilight Zone, of which Matheson wrote fourteen episodes, including classics such as “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” and “Nick of Time.” That’s also why low budget films based on his work – The Incredible Shrinking Man (budget $750,000), The Last Man on Earth ($300,000), Duel ($450,000) – generally fare better than big budget films such as 1998’s What Dreams May Come ($90 million) and 2009’s The Box ($30 million). The 2007 film I Am Legend, starring Will Smith, cost $150 million to make. It was profitable but hasn’t achieved the cult classic status of the less costly earlier adaptations. And the fact that seventeen years have elapsed without a sequel appearing suggests, in this sequel-crazed era of ours, that Warner Brothers wasn’t overly excited by its ROI.

Five years before Matheson sicced his vampires on L.A., George R. Stewart, in his novel Earth Abides, unleashed a plague that killed almost everyone on the planet. Earth Abides was probably the first great American post-apocalypse novel of the post-WWII era. It kicked off a vogue for the genre that would soon produce such iconic titles as A Canticle for Liebowitz, Fail-Safe, On the Beach, and The Stand (King has cited it as a major influence on his novel). Cormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2006 novel, The Road, is also a direct descendent of Earth Abides, as is Emily St. John Mandel’s 2014 novel Station Eleven. P.D. James’s 1992 novel, The Children of Men, features an academic from a prestigious British university struggling to comprehend a world that is slowly depopulating. It echoes Earth Abides, which features an academic from a prestigious American university struggling to comprehend a world that has rapidly depopulated. Ray Bradbury’s own Cali-pocalypse, the short story “There Will Come Soft Rains,” was published just six months after Earth Abides and may well have been inspired by it. And of course, there was I Am Legend. Stewart was a better writer than Matheson, so the prose in Earth Abides is crisp and intelligent, lacking the jerkiness of I Am Legend. Alas, Stewart lacked Matheson’s ability to produce clever plot twists, so his novel isn’t always as compelling as I Am Legend. Rather it is often just a leisurely stroll through the blasted heath of a largely depopulated United States of America. Nonetheless, it is beautifully done.

Stewart was born in Sewickly, Pennsylvania, in 1895, and grew up in Indiana, Pennsylvania, the hometown of actor James Stewart, who was no relation. His life was often affected by the types of diseases that pandemics are made of. In 1906, his five-year-old brother contracted typhoid fever and died shortly thereafter of pneumonia. Stewart himself contracted pneumonia during the Great Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918, probably as a result of catching the flu. The disease killed 20 million people worldwide, 600,000 of them in the U.S. Stewart survived, but he was plagued with lung problems for the rest of his life. His daughter, Jill, had a tuberculosis scare when she was a child. All this might explain why pandemics were so fascinating to him.

His early life brought him into contact with a number of future cultural icons. After moving to Southern California with his family in 1908, he became best friends with a boy named Buddy DeSylva, who would go on to write or co-write a number of popular songs, including April Showers, The Best Things In Life Are Free, Button Up Your Overcoat, The Birth of the Blues, and California, Here I Come. Stewart attended Pasadena High School with future film director Howard Hawks. He was a member of the tennis team and once played a match against future Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Thornton Wilder. At Princeton, Stewart once participated in a relay race with F. Scott Fitzgerald. His wife was the daughter of Marion LeRoy Burton, the second president of Smith College and a close personal friend of President Calvin Coolidge. Through her, Stewart became friendly with many prominent educators and writers, including Robert Frost and Carl Sandburg. On December 6, 1941, the Stewarts were in New York for a party that was being held to celebrate the publication of Storm. The next morning, they happened to encounter John Steinbeck, who informed them of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Throughout his life, he had an almost Zelig-like ability to find himself connected, if only tangentially, to prominent people.

As an adult, Stewart was a renowned scholar, an English professor at the University of California at Berkeley who was fascinated by history, geography, and, in particular, American landscapes. He was also a prolific writer, and Earth Abides wasn’t the only one of his books to gain popularity. Wikipedia’s entry for Stewart notes that “his work was not known well during his lifetime, and is now almost forgotten.” Neither of those assertions is remotely true. If he never became a brand-name author, it’s mainly because he wasn’t much interested in self-promotion. He preferred to spend his time reading, writing, researching, and teaching. But he had a very successful career as an author. Like Richard Matheson, Charles Portis (True Grit), Walter Tevis (The Hustler), John Ball (In the Heat of the Night), Jack Finney (The Body Snatchers), Richard Condon (The Manchurian Candidate), and many others, his books were far more famous than his name. His 1936 nonfiction work, Ordeal By Hunger: The Story of the Donner Party, earned Stewart the Silver Medal of the Commonwealth Club of California, a prize awarded to the year’s best work of nonfiction about California. It helped to earn him a promotion at U.C. Berkeley, and brought him enough money to buy a house for his family in the Berkeley Hills. Twenty-four years later, in an introduction to an updated 1960 edition of the work, Stewart noted that the book, “has been read by thousands of people [and] has already begun to achieve a kind of classic quality.” Few unknown novels are given a hardcover reprint to celebrate a quarter century in print. The book remains in print to this day. In The Life and Truth of George R. Stewart: A Literary Biography of the Author of Earth Abides, author Donald M. Scott notes of Ordeal By Hunger: “The book is one of three of Stewart’s works which still have wide distribution. (The other two are Pickett’s Charge and Earth Abides.) But it is much more than a popular book. It is a book which helped shape our time.” By making the landscape of Northern California’s Sierra Mountains “one of the chief characters of the tale” (Stewart’s words), Stewart became one of the first progenitors of the contemporary environmental narrative, a genre that wouldn’t flourish until the 1960s. He was also one of the forefathers of the so-called nonfiction novel, fact-based works written in a novelistic style. Later examples include A Night To Remember, Walter Lord’s 1954 book about the Titanic disaster, and In Cold Blood, Truman Capote’s 1966 book about the massacre of a Kansas family in 1959. Stewart would burnish his environmental bona fides with several subsequent novels, including Storm (1941) and Fire (1948). The first of these, as the title notes, is about a giant storm that germinates in Siberia but doesn’t fully form until it is somewhere off the coast of Japan, after which it gradually gains strength as it moves inexorably towards California. It is perhaps the best book-length examination of the weather phenomenon known as “the butterfly effect,” although that term didn’t exist at the time. The book has human characters – a meteorologist for the state, a dam superintendent, a telephone lineman, etc. – but they all play minor roles and many are not even given names. The only real character is the storm itself. It is huge and it is powerful and it has the potential to take thousands of human lives as it starts pounding the northern Sierra Mountain range with snow and rainwater that could sweep away much of Sacramento, but Stewart doesn’t portray it as evil or malicious. It is a creature of nature, like a lion or a shark, and it is only doing what comes naturally to it. As Nathaniel Rich pointed out in an introduction to the New York Review of Books edition of Storm, Stewart shows how the storm, by knocking down a single telephone pole, sets in motion a chain of events that “leads a Boise man to lose a prospective job, denies a girl in Omaha a final conversation with her dying mother, and ensures a divorce in Reno. Such chains of events recur frequently throughout the novel – falling air pressure in Winnipeg causes a store owner in Sacramento to buy a new car; heavy rain over Central California brings suicides in Florida.”

Kim Stanley Robinson has likened Storm to the so-called “it narratives” of the eighteenth century. Sometimes called the “novel of circulation,” an it narrative follows an inanimate object – a coin, a gun, a cloak, etc. – from one owner to the next, in order to consider the manner in which personal property illuminates the characters who own it and/or the society in which is circulated. At least three of Stewart’s novels can be said to have nonhuman main characters: Storm, its sequel Fire, and Doctor’s Oral, wherein a Ph.D. student’s oral exam takes center stage.

Six years after Storm was published the book was reprinted as a part of the Modern Library’s series of classic books. The book has been republished many times since, most recently in 2021 as part of the abovementioned NYRB Classics series. The editors of the series noted that, “With Storm, first published in 1941, George R. Stewart invented a new genre of fiction, the eco-novel.” This isn’t quite true. As noted, Joseph Conrad’s 1902 novella Typhoon did something similar, as did the 1936 novel The Hurricane, by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall. And, in fact, Daniel DeFoe’s nonfiction book The Storm (1704) describes a massive hurricane that hit England in 1703. But none of those works committed to the idea of portraying the weather as a living, breathing character as thoroughly as Stewart did in Storm. Not until 1997 and the publication of Sebastian Junger’s nonfiction book The Perfect Storm would an American author so successfully milk the reading public’s fascination with deadly weather. But it is far from the only work that seems to have been written by someone knowledgeable of Stewart’s work. Several of Stephen King’s stories – The Storm of the Century and The Mist, for example – deal with horrific atmospheric events in a way that seems to gesture to Stewart’s novel. Arthur Hailey’s 1968 bestseller, Airport, tells the story of a massive storm that virtually shuts down a major American airport. George Stone’s 1977 novel, Blizzard, buried the entire American east coast under a monstrous snowfall. One year later, Arnold Federbush buried New York City under Ice! Will Holt’s 1979 novel, Savage Snow, buried Boston under a blizzard. Thom Racina did the same thing to L.A. in 1977’s The Great Los Angeles Blizzard. Three years later, Edward Stewart (no relation to George) published a novel called The Great Los Angeles Fire, which was indebted to Fire. Nathaniel Rich’s 2013 novel, Odds Against Tomorrow, combines elements of Storm and Earth Abides by using a massive tropical storm called Tammy to send New York City back into a pre-modern condition. The book also name-checks Bradbury’s “There Will Come Small Rains.” More recently, Lily Brooks-Dalton’s 2022 novel, The Light Pirate, about a massive tropical storm called Wanda that reshapes the landscape of Florida, took some of Stewart’s ideas and relocated them to the other side of the continent. David Koepp expanded on Stewart’s idea in his 2022 novel Aurora, in which a solar storm knocks out power all over the globe, for months on end.

Walt Disney was so impressed by the way Stewart wrote about American places that, in the late 1940s, he invited the author to spend a week at the Disney Studios in Los Angeles. Disney wanted to create a series of films about small-town America and he asked Stewart to pitch some ideas (the films were never made). At that time, Disney was also secretly mulling the idea of creating an Americana-themed park which, at the time, he was calling Disneylandia. Stewart’s biographer, Donald M. Scott, believes Stewart might have unknowingly had an influence on this project. “Disney clearly knew Stewart’s work,” Scott writes, “and probably knew of his boyhood in a town like the one where the Disneys had their boyhoods; Stewart’s ideas about American folklore would have been of great interest to Walt Disney as he thought about the Disneylandia project.” (Around 1910, when George was 15, his father purchased an orange grove two miles from Anaheim. Disneyland is built on a former orange grove in Anaheim. The route George once walked from town to his family’s orange grove is now a main thoroughfare to Disneyland. In Stewart’s childhood, he rarely saw a vehicle on the road.)

Storm is one of those rare novels that actually have had profound real-world effects. The success of the novel helped popularize the practice of giving (usually feminine) names to tropical storms, which is now commonplace throughout the U.S. (although, since the late 70s, the names are just as often masculine as feminine). A meteorologist in the book christens the titular storm “Maria” (pronounced ma-RYE-uh, according to a note by Stewart), a fact that inspired the songwriting team of Alan J. Lerner and Frederick Loewe to write a song titled “They Call the Wind Maria” for their 1951 Broadway musical Paint Your Wagon, which is set in Northern California’s Gold Country. The song has since become a staple of both American show tune catalogs and folk music catalogs. Vic Moitoret, a U.S. Navy meteorologist, was so impressed by Storm that he created the George R. Stewart Fan Club. Another fan formed a rival group called The Friends of George R. Stewart.

I own three different editions of Storm, a 1983 Bison Books edition with an introduction by Wallace Stegner, a friend of Stewart’s and a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist; a 2003 edition published by Heyday Press of Berkeley and containing a worshipful introduction by eco-novelist Ernest Callenbach, the author of Ecotopia; and the 2021 edition, which contains an introduction by novelist Nathaniel Rich, author of the eco-novel Odds Against Tomorrow. Stegner’s introduction notes that Storm “was a popular book, a bestseller and a Book-of-the-Month Club choice, but it has not disappeared like most popular novels. Its re-publication after more than forty years indicates its staying power.” Forty-one more years have passed since Stegner wrote those words and the book’s staying power is undiminished. In 1959, the novel was adapted as an episode of ABC’s Walt Disney Presents TV series and given the title “A Storm Called Maria.”

Storm was so successful that readers of the book began writing to Stewart and suggesting that he write novels about other acts of God, such as volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. Stewart prided himself on not being pigeon-holed as a writer, so he tried to resist these entreaties. But his publisher became insistent. Thus, in 1948, Stewart followed up Storm with a sequel called Fire, whose main character is a California wildfire, nicknamed Spitcat, that rages out of control. Alas, Lerner and Loewe never saw fit to give us a song called “Spitcat,” but Walt Disney Presents adapted it for TV. Fire has been republished many times through the years and a new edition will be released as part of the NYRB Classics series on August 13. Stewart’s 1945 nonfiction book, Names on the Land, has also been reprinted as an NYRB Classic. The book inspired a lot of Americans to take up an interest in place names. A few years later, in 1951, Stewart helped found the American Name Society, an organization dedicated to the study of American place names. The society still exists. Shortly after Stewart published Names on the Land, Ray Bradbury published a short story called The Naming of Names, about human colonists on Mars who gradually begin to intuit the language of the long-dead Martian race and then start changing the names of landscape features – the Roosevelt Canal, the Rockefeller Mountain Range – back to their original names – Tirra Canal, the Pillan Mountains. It seems likely that Bradbury was inspired by Stewart’s book. He writes of one of his colonists, “He returned to his philosophy of names and mountains. The Earthmen had changed names. Now there were Hormel Valleys, Roosevelt Seas, Ford Hills, Vanderbilt Plateaus, Rockefeller Rivers, on Mars. It wasn’t right. The American settlers had shown wisdom, using old Indian prarie names: Wisconsin, Minnesota, Idaho, Ohio, Utah, Milwaukie, Waukegan [Bradbury’s birthplace], Osseo. The old names, the old meanings.” Almost anyone familiar with contemporary American literature of the time would have recognized Stewart’s influence on the story. Later, Bradbury seemed to want to disavow that Stewart had any influence on the story, and he changed the title to “Dark They Were and Golden-Eyed.” Ironically, Bradbury originally gave his story a name similar to the name of Stewart’s book about names, and then changed the name to disguise its origins, further emphasizing Stewart’s philosophy about the power of names to alter perceptions. In the late 1940s, the Mutual Broadcasting System had a popular radio program called The Casebook of Gregory Hood, a mystery series. The August 26, 1946, episode was called “The Ghost Town Mortuary” and was set in Berkeley. It featured this exchange of (clunky) dialog among the main characters:

GREGORY: This place is handy for the one person I think can help us on this case.

SANDY: And who is that person?

GREGORY: Professor George Stewart of the University English Department.

MARY: Oh yes! He wrote Storm. A wonderful book.

GREGORY: True, but what is more to our immediate point is the fact that Random House recently published his new book Names on the Land. It’s a classic and definitive study of American place-naming. His virtues are many, including a fine sense of entering on cue. Hello, George.

STEWART: I got your message, Greg, and it all sounds frightfully mysterious. What’s your problem?

Gregory Hood, a private eye, explains that he is looking for a missing young woman who dashed off a telegram before disappearing. It contained a message of a single word: Difficult. Hood asks Stewart, an expert on place names, if it could be a reference to a town of some sort. Stewart explains that there is an American town called Difficult. Apparently, when the town’s founding fathers filed the town’s name with the U.S. Postal Service, the Service responded with a message that read, “THE NAME OF YOUR TOWN IS DIFFICULT.” The town fathers assumed that the postal service had overridden their choice of a name and had dubbed the town Difficult. And so that became the town’s name. George R. Stewart, with his vast knowledge of American place names, solved the mystery. (Stewart’s book included references to risqué place names such as Nipple Butte, Nigger Hill, and Shit House Mountain, but those couldn’t have been mentioned on the radio.) Names on the Land proved so successful that he later followed it up with a sequel, Names on the Globe. He was also an expert on American family names, and once testified in a murder trial as an expert witness on the subject. He produced a book on the topic called American Given Names.

As a teacher he shaped the minds of many students who would also grow up to be influential. In the 1930s, an aspiring writer and U.C. Berkeley student named Robert Galen Fogerty took every class he could from Stewart. According to Donald Scott, “Fogerty believed Stewart had a great influence on his life and character – and on the music of the 1960s group Creedence Clearwater Revival, since Creedence founders Tom and John Fogerty were Robert Fogerty’s sons.” Stewart was obsessed with American folklore and landscapes and people, and probably no rock band explored those themes more thoroughly than CCR. At least three CCR songs – “Have You Ever Seen the Rain?”, “Who’ll Stop the Rain?”, and “Bad Moon Rising” – sound as if they might have been directly influenced by the novel Storm, with their lyrics about “seeking shelter from the storm” and “hurricanes a-blowin’” and “rivers overflowin’” and “nasty weather” and “clouds of mystery pourin’” and “there’s a calm before the storm.” Stewart’s novel Fire seems to have had an influence on John Fogerty’s songwriting also, in particular on the song “Effigy,” which begins, “Last night I saw a fire burnin’” and then later adds, “Last night I saw the fire spreadin’.” In a single sentence from the novel Storm, you’ll find material that could have inspired three different CCR songs:

Against all the cities of the plain the storm was beating…Lodi of the grapes…Porterville of the oranges; Tulare of the cotton.

John Fogerty wrote songs titled “Lodi” and “Porterville.” And his band also covered the Huddie Ledbetter song “Cotton Fields.” To one degree or another, nearly every Creedence song sounds as if Stewart might have had a hand in it.

It seems likely that Michael Crichton was influenced by Stewart’s work. His 1969 bestseller, The Andromeda Strain, about a plague that threatens mankind, seems to have been written by someone familiar with Earth Abides. But Crichton seems to have been familiar with both Storm and Fire as well. His best screenplay was probably for the film Twister, a film about a weather phenomenon. And the fact that he gave the plague in The Andromeda Strain a female name suggests familiarity with Storm, as well.

Bestselling books, Broadway musicals, national radio broadcasts, murder trials, Berkeley lecture halls, Disney TV movies, Ray Bradbury short stories, CCR songs, Michael Crichton’s writings – Stewart’s influence was seemingly everywhere in America in the mid-twentieth century. Anyone who could write of Stewart, “his work was not known well during his lifetime, and is now almost forgotten” simply wasn’t paying attention. Signed copies of his novels are listed for sale at the American Book Exchange for as much as $4,750. Works by forgotten authors rarely fetch prices that high. If university American Lit departments haven’t embraced Stewart as enthusiastically as they have the likes of Cormac McCarthy or Toni Morrison, it’s probably at least in part because his work was connected in numerous ways to pop cultural mainstays such as Disney, rock-n-roll, radio mystery programs, fan clubs, Broadway musicals, sci-fi, and so forth – things often looked down upon by academic snobs.

Earth Abides, his most popular novel, won the very first International Fantasy Award back in 1951, an impressive accomplishment when you consider that it was published in the same year as George Orwell’s 1984. It has appeared on numerous lists of the best science-fiction novels of all time, generally near the very top. The book has had a profound influence not just on Stephen King but on numerous other creative artists as well. Carl Sandberg thought it was one of the greatest books of its time, as did Wallace Stegner. Jimi Hendrix cited it as his favorite book and it served as the inspiration for his song “Third Stone from the Sun.” In a glowing introduction to Walter Tevis’s 1980 apocalypse novel, Mockingbird, Jonathan Lethem writes, “Chunks of books like 1984 and Brave New World and Earth Abides seem to be swallowed here, likely because Tevis knew those books…” Philip K. Dick’s Cali-pocalypse, Dr. Bloodmoney, mostly takes place, like Earth Abides, in and around Berkeley, after a nuclear catastrophe has knocked much of humankind back into a pre-modern era of horse-drawn vehicles and such. It seems almost certain that Dick’s book was influenced by Stewart’s. And here’s what novelist James Sallis had to say about Earth Abides in a 2003 appreciation written for the Boston Globe: “This is a book, mind you, that I’d place not only among the greatest science fiction, but among our very best novels. Each time I read it, I’m profoundly affected, affected in a way only the greatest art – Ulysses, Matisse or Beethoven symphonies, say – affects me. Epic in sweep, centering on the person of Isherwood Williams, Earth Abides proves a kind of antihistory, relating the story of human kind backwards, from ever-more-abstract civilization to stone-age primitivism…Making Earth Abides a novel for which words like elegiac and transcendent come easily to mind…”

“Epic” is the right word for Earth Abides. Prior to the arrival of Stephen King’s The Stand, most apocalypse novels, somewhat counterintuitively, tended to be short, as if the hard work of destroying the planet was just too much for the author to bear. I Am Legend runs 174 pages in length. Robert Lewis Taylor’s Adrift in a Boneyard runs 189. Planet of the Apes (another Charlton Heston airplane read?) runs 128 pages. Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers runs 216 pages. Pat Frank’s Mr. Adam runs 224 pages. Philip K. Dick’s The World Jones Made runs 211. John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids runs 241. And Ray Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains” is only five pages and maybe 1,200 words long. But Earth Abides is 426 pages long. Stewart was the first post-war novelist to really tax his imagination and try to figure out what the end of life as we know it would look like. And his book remains one of the preeminent titles in the genre.

In the late 1950s, prolific movie producer Robert L. Lippert wanted to make a film version of Earth Abides but, after the box office failure of 1959’s The World, the Flesh and the Devil, his frequent collaborator, screenwriter Harry Spalding, convinced him that another last-man-on-earth film would be difficult to sell to America’s theater owners (Lippert himself owned a chain of 139 theaters). But just a few years later, Lippert, determined to give the genre another try, bought the film rights to Matheson’s I Am Legend and made the movie The Last Man on Earth (Matheson didn’t like the film and took his screenwriting credit under the pseudonym Logan Swanson). As a fan of B-movies and genre pictures, I can’t help but wonder what a Robert L. Lippert-produced film version of Earth Abides might have looked like. It is one of the many great what-ifs of Hollywood cinema.

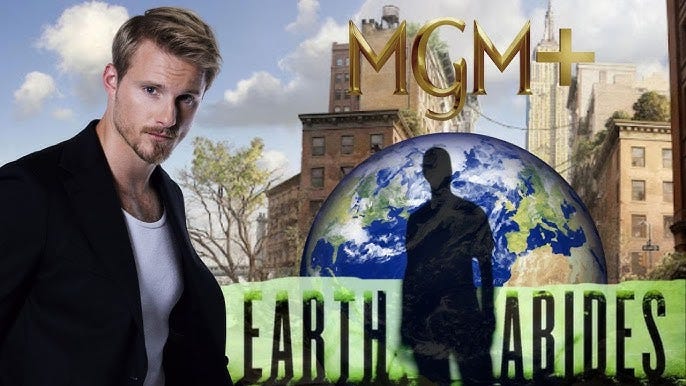

Fortunately, Hollywood has finally gotten around to embracing Stewart’s classic novel. Amazon Studios and the MGM + streaming service have produced a six-episode limited series based on the novel that is scheduled for release later this year, almost exactly 75 years after the book’s original publication date.

When the project was completed, showrunner Todd Komarnicki, told Deadline magazine, “It has been an unmitigated thrill to adapt such a seminal sci-fi work, and the themes illuminated by George Stewart 75 years ago could not be more meaningful and timelier for the world we are living in today.” It will be interesting to see exactly how Komarnicki and company have adapted Stewart’s novel. As mentioned, it is not heavy on plot. Earth Abides is the story of Isherwood “Ish” Williams, a graduate student at U.C. Berkeley. As the novel opens, he is in a wilderness area of Calaveras County, California, doing research on his thesis: The Ecology of the Black Creek Area. On page one, he gets bitten by a rattlesnake, after which he retreats to a nearby cabin. Feverish and delirious he holes up for a day or two. He doesn’t know it yet, but while he has been alone in the wilderness, an “unknown disease of unparalleled rapidity of spread” has killed off nearly everyone on earth. Stewart doesn’t spell it out, but the rattlesnake venom seems to have spared Ish’s life. Later, he will meet other survivors, at least one of which was bitten by a rattlesnake at some point in her life. Of the disease, Stewart writes, “No one was sure in what part of the world it had originated; aided by airplane travel, it had sprung up almost simultaneously in every center of civilization, outrunning all attempts at quarantine…It might have emerged from some animal reservoir of disease; it might be caused by some new micro-organism, most likely a virus, produced by mutation; it might be an escape, possibly even a vindictive release, from some laboratory of bacteriological warfare. The last was apparently the popular idea. The disease was assumed to be airborne, possibly upon particles of dust. A curious feature was that the isolation of the individual seemed to be of no avail.”

Stewart was one of the first fiction writers to illustrate how the combination of air travel and disease might threaten the population of the entire planet. “As George Stewart had predicted in Earth Abides,” writes Dorian Lynskey, “viruses came to represent the dark side of air travel and international commerce. When Earth Abides was published in 1949, around two million people traveled on international commercial air flights; at its pre-Covid peak, the figure was four and a half billion.” In his 1994 nonfiction bestseller The Hot Zone, author Richard Preston was still hammering home a point that Stewart had made more than four decades earlier: “A hot virus from the rain forest lives within a twenty-four-hour plane flight from every city on earth. All of the earth’s cities are connected by a web of airline routes…Once a virus hits the [web], it can shoot anywhere in a day – Paris, Tokyo, New York, Los Angeles, wherever planes fly.”

With its many parallels to recent events, it’s easy to see why the executives at MGM + might have thought that the post-pandemic era was finally the right time for Hollywood to adapt Stewart’s novel. Although the recent pandemic killed “only” about 20 million people worldwide, Stewart’s novel allows us to see what might have become of the planet had Covid-19 proved to be much more fatal. The most recent American edition of Earth Abides was published in the plague year of 2020 and contains an introduction written by novelist Kim Stanley Robinson in April of that year in which he explicitly makes the connection between Stewart’s fictional plague and our own very real one. But he begins his introduction by noting that, “This novel, George Stewart’s masterpiece, is exceptionally ambitious, wide-ranging, graceful, and wise. It’s one of the greatest novels in the subgenre of science fiction now called post-apocalyptic (in Stewart’s time it might have been called an ‘after the fall’ novel), and very worthy of the permanent place in science fiction and in American literature that it has achieved.” Robinson (author of the 1984 Cali-pocalypse novel The Wild Shore) shrewdly notes that, just as Storm bore a resemblance to Daniel Defoe’s The Storm, Earth Abides shares similarities to Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Journal of the Plague Year (1722). He writes, “Stewart reminds me of Daniel Defoe. The two writers share many qualities: a wide-ranging education, curiosity about how societies work, and a clear evocative style…As an English professor of the mid-twentieth century, it’s certain that Stewart would have been well-versed in Defoe’s work.” In fact, Robinson Crusoe is referenced several times in Earth Abides, just as Dracula is referenced in I Am Legend. Both of these apocalyptic classics acknowledge their forebears. Stewart was probably also aware of Annie Carey’s 1873 novel of circulation called The History of a Book, which follows the fortunes of a copy of Robinson Crusoe, beginning with the publishing process and moving on from there. Carey’s novel combined two of Stewart’s passions, last-man narratives and circulation narratives. An even bigger influence on Stewart’s work was Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, with its emphasis on maps and seas and landscapes and largely unpopulated places. Stewart discovered the book as a child, and it changed his life. “Treasure Island had given Stewart an epiphany,” writes Donald M. Scott, “fundamental to everything in his work that followed.”

In the first fifty pages of Earth Abides, Ish returns to his family’s home on the fictional San Lupo Drive in Berkeley (modeled on Stewart’s own home on San Luis Road) and wanders around the Bay Area looking for survivors. He finds a few but they are mostly castoffs and crazy people, driven mad by the Great Disaster. Ish has no desire to form a community with any of them. Just as the house on Cimarron Street serves as the focal point of I Am Legend, the house on San Lupo Drive will eventually become the focal point of Earth Abides. But first Ish takes off in his car for a cross-country trek across the United States. This eastward journey reverses the course of Stewart’s own journey in life. Like a surprising number of bestselling American authors (Joseph Wambaugh, Dean Koontz, Martin Cruz Smith, Michael Chabon, etc.), Stewart was born in Pennsylvania but spent most of his professional life in California. This opening section of the novel lasts about 45 pages and culminates in New York City, where Ish and his dog, Princess, motor down a completely empty Broadway. After that, he turns around and begins the long drive back to California. In many ways this section is the best part of the novel. It certainly appears to have been the part of the book that Stewart enjoyed writing most. It offered him a chance to muse upon just what might happen to the American landscape if humans largely disappeared from it. He describes house pets turning feral again. And, he writes, “As with the dogs and cats, so also with the grasses and flowers which man had long nourished. The clover and the bluegrass withered on the lawns, and the dandelions grew tall. In the flowerbed the water-loving asters wilted and drooped, and the weeds flourished. Deep within the camellias, the sap failed; they would bear no buds next spring. The leaves curled on the tips of the wisteria vines and the rose bushes, as they set themselves against the long draught.”

He writes movingly of the dairy cows who have starved to death in their milking barns, the thoroughbred horses who have died in their stalls, the house pets who can’t get out of their houses and so die of malnourishment and thirst. He muses on what might become of the cattle. With no men to kill them, wolves and coyotes are likely to proliferate again, and that will eventually keep the cattle population from overrunning the American West. He speculates upon how the landscape will change as man’s dams and levies begin to fail. This section of the book is so engrossing that it inspired journalist Alan Weisman’s 2007 nonfiction book The World Without Us, which speculates upon how quickly planet earth would return to its natural state if man were to disappear.

“What makes Earth Abides remarkable,” writes Dorian Lynskey, “is Stewart’s serious engagement with the reality of an untenanted world. In most last-man stories, cities are largely intact, if sad and tatty, but Stewart, a prolific historian and toponymist, recognized that the world as we know it requires an enormous amount of maintenance. As Isherwood wanders equably around an unraveling America, Stewart keeps breaking off for lyrical disquisitions on what would happen if there were nobody to run the power stations, unblock the drains, fight the fires and do all those other jobs that we take for granted. How quickly it all falls apart.”

All of this works very well in a novel, but it’s difficult to see how it can be made cinematic. Fortunately for MGM +, Ish does eventually return to the house on San Lupo Drive, and he does begin to gather about him a community of survivors. He takes a (common law) wife, Emma, an African-American, and they have children together. (The producers of Star Trek have been given a great deal of praise for featuring a kiss between a white man and a Black woman in the 1968 episode titled “Plato’s Stepchildren,” but, nearly twenty years earlier, Stewart wrote an interracial marriage into his science-fiction classic and has never been given much credit for it.) Many of the other survivors also pair up and begin producing children. But as the last of the electric utilities finally dies out, Ish sees the younger generation of survivors begin to revert to a sort of pre-modern state of nature. Not all of this is terribly believable. Even in 1949 America was awash with handguns and rifles. But the younger generation of survivors tend to eschew these, preferring to use bows and arrows they make themselves (they hammer coins, which are now useless, into arrowheads). Likewise, chickens soon appear to go extinct, the victim of coyotes and wild dogs and their own over-domestication by mankind. They can’t survive without man, and so they die off and the humans no longer have a ready supply of eggs. This, too, seemed unlikely to me. At one point, some of the younger people decide to drive off to Los Angeles in order to see a bit more of the world. When they return, they bring a menacing stranger named Charlie with them. For a while, it looks as though Charlie might become the great villain that this novel sorely lacks. But, though he brings tragedy in his wake, he never rises to the level of villain. Stewart seems to think that Decadence itself is sufficiently villainous.

Kim Stanley Robinson sings the praises of Stewart’s characters. “The novel stays tightly focused on a single character, with a typical array of secondary characters. This is not to say that these characters are vague; they are quite distinct and well-drawn. Ish may be a kind of everyman, but his thinking and emotional life are clear and absorbing. He stands up well as a character even when compared to those in the mainstream novels of the 1940s that feature a hyperintense focus on a single consciousness. Ish’s interior life is lively, serious, intelligent, and believable. His angst over marrying a person of a color looks antiquated now, but was in keeping with the culture he was raised in, and a sign of how he has to change.” I agree with Robinson about Ish; he is a well-drawn and interesting character. But he is the only well-rounded character in the book. As Stegner noted in his introduction to Storm, in Stewart’s novels “the characters seem to have interested him less for themselves than for their function as working parts of larger social entities – families, frontier communities, tribes, corporations, civilizations.” It will be interesting to see what Todd Komarnicki does with these mannequin-like secondary characters. It will also be interesting to see what he comes up with for a plot. A group of Northern Californians undergoing a slow but largely undramatic return to an earlier state of human civilization doesn’t exactly scream out “Must-see TV!” But whether or not MGM + succeeds in making its version of Earth Abides engrossing, Stewart succeeded with his. Like most of his famous novels, this is a meditation on America – its landscapes, its animals, its people, its built environment, its natural environment. And few authors have ever loved American geography more than Stewart, or written about it better than he did. It’s a novel to savor rather than to race through.

Stewart (1895-1980) was part of a loose and unnamed school of writers that flourished in the mid-twentieth century. Born near the beginning of that century, they were mostly male academics who taught in western universities and wrote knowledgably about the American west. If Louis L’Amour and his pop-fiction brethren were the “tails” side of the Western literary coin, these men were the intellectual “heads” side. Among the most prominent of these writers were Stegner (who won a Pulitzer Prize for Angle of Repose in 1972), A. B. Guthrie (who won a Pulitzer in 1950 for The Way West, published two weeks before Earth Abides), Conrad Richter (who won a Pulitzer for The Town in 1951), Robert Lewis Taylor (who won a Pulitzer for The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters in 1959, and published his own apocalypse novel, Adrift in a Boneyard, two years before Earth Abides appeared), H.L. Davis (who won a Pulitzer in 1936 for Honey in the Horn), Walter Van Tilburg Clark (author of the classic 1940 Western The Ox-Bow Incident), Jack Schaefer (author of Shane, published one week before Earth Abides), and George R. Stewart. For most of the last 70 years almost anyone familiar with these men and their works would have ranked Stewart last in importance and least likely to be remembered by posterity. After all, he never won a Pulitzer, never had a book adapted for a major motion picture, and never received a glowing profile in the New York Times. Nowadays that assessment appears to have been shortsighted. Guthrie and Clark, both great writers, appear to be fading from cultural prominence. Ditto Richter and Schaefer. Hollywood seems to have no interest in them, and they are exactly the kind of legacy authors who get dropped when school syllabuses are updated to make them more inclusive of women and minorities. Way back in 2009, Timothy Noah wrote an essay for the New York Times about how Wallace Stegner, a towering figure in the literature of the West, was already being forgotten. Even at Stanford University, where he ran the Creative Writing department for decades, his works are not widely known or read any longer.

But George R. Stewart, never that famous to begin with, seems to hang in there, year after year, decade after decade. Ordeal By Hunger, Storm, Fire, Pickett’s Charge, Names on the Land – every generation seems to rediscover these treasures and bring them out in new editions, with new introductions, and new interpretations of their place in the cultural landscape. Times change, literary fashions come and go, but Stewart abides.

Paradoxically, many Cali-pocalypse and Cal-dystopia tales end hopefully. Whereas writers rarely seem to have any compunctions about destroying decaying older metropolises such as London (John Christopher’s The Death of Grass), Manhattan (Walter Tevis’s Mockingbird), or Tokyo (Yoko Tawada’s The Emissary), many of them seem to flinch at the idea of completely destroying California. The Golden State has been a promised land to people the whole world over since at least the 1849 Gold Rush, and the idea of a world without some shining beacon of hope in the darkness is apparently too much even for authors of apocalypse novels. In her 1989 novel The City, Not Long After, author Pat Murphy depicts postapocalypse San Francisco as…an artists’ colony. In his 1984 novel The Wild Shore, Kim Stanley Robinson depicts postapocalypse Southern California as…a pastoral collection of small farming and fishing villages. In Jean Hegland’s Into the Forest (1996) and Eden Lepucki’s California (2014), postapocalypse California has largely reverted to a sort of prelapsarian wilderness area, something akin to what the first European settlers to the state found when they arrived there. It isn’t exactly paradise but, if you have a taste for frontier living, you just might enjoy it. At least there is no more rush-hour traffic or smog to deal with. And even in Earth Abides, the reader is left with a sense of a new paradise growing up from the ashes of the older one. Only Richard Matheson, among major Calipocalypse authors, seems to have had the courage to completely decimate the Golden State. By the end of I Am Legend, humanity is dead and has been replaced by zombie-like vampires (or, perhaps, vampire-like zombies), leaving the reader with little desire to actually step into the novel and tough it out in this brave new world. This isn’t a return to California’s pioneer days. It is a descent into hell.

But Matheson was an outlier. And I Am Legend, at about 25,000 words, is one of the shortest novels in the entire canon of Cali-pocalypse literature. Apparently even the tough-minded Richard Matheson couldn’t stand to watch California burn for more than a short while.